75 Worked Examples: Fluid Flows & Fluid Dynamics

Many of these worked examples have been fielded as homework problems or exam questions.

Worked Example #1

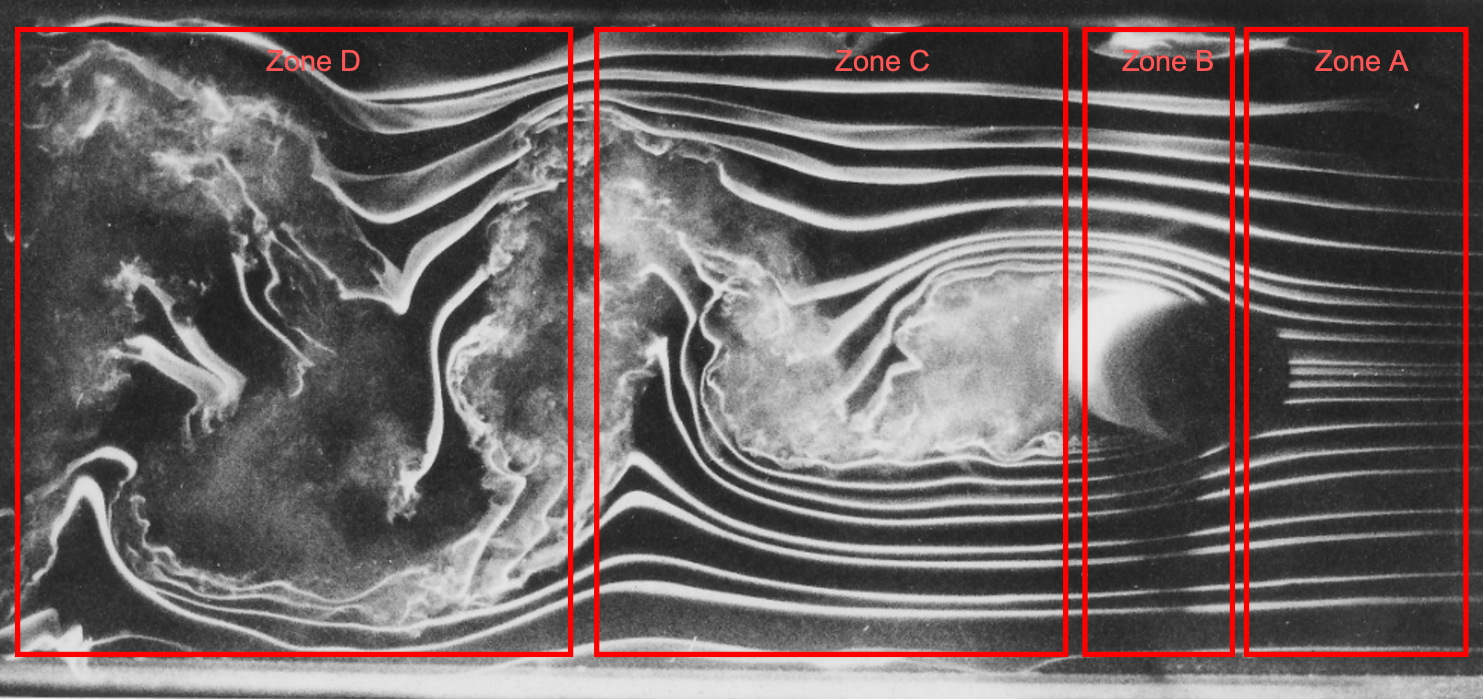

Examine the flow visualization of the circular cylinder in the photograph below. Discuss the nature of the flow in Zone A. Is the flow here steady or unsteady? Identify the streamlines. Explain the nature of their curvature and spacing. Where is the highest velocity, and where is the lowest? Discuss the nature of the flow in Zone B. Is the flow here steady or unsteady? Where does the flow separate from the cylinder? What happens to the flow after that? Discuss the nature of the flow in Zone C. Is the flow here steady or unsteady? Is it laminar or turbulent, and where? Is it transitional? Identify any eddies or vortices. Discuss the nature of the flow in Zone D. While turbulent and unsteady, are there still any laminar flow regions? Why does the original smoke diffuse?

Zone A: The flow is steady and primarily laminar in Zone A. The streamlines are smooth, indicating that the flow is free from turbulence. The streamlines are straight and closely spaced near the front of the cylinder. The curvature is relatively mild as the streamlines wrap around the leading edge half of the cylinder. The highest velocity occurs where the streamlines are closest together, which occurs near the poles of the cylinder. There is a stagnation flow region on the front of the cylinder, where the flow is brought to rest. The curvature of the streamlines increases as they approach the cylinder, and the spacing between them decreases, which implies that the flow is accelerating as it passes around the cylinder.

Zone B: The flow in Zone B is transitioning to a more unsteady state. This is the region where flow separation occurs from the cylinder. The flow begins to separate from the surface of the cylinder near its equator; you can identify the separation point where the streamlines start to diverge from the surface. After the point of separation, the flow begins to form turbulent eddies, and there is evidence of recirculation where the flow curls back on itself. This marks the onset of the unsteady wake behind the cylinder, and disturbances in the flow start to appear as it loses all of its initial laminar characteristics.

Zone C: The flow in Zone C is unsteady and turbulent. This region is characterized by the formation of larger eddies and vortices, which are visible in the image as swirling, rotational flow patterns. The flow is likely still in some transitional state between laminar and fully turbulent. The eddies grow more prominent as the flow develops downstream and becomes increasingly turbulent. Several discrete eddies and vortices are visible in this region. These are the characteristic features of the unsteady wake behind the cylinder, often referred to as a Kármán vortex street.

Zone D: The flow in Zone D is turbulent and would be classified as unsteady. By default, turbulent flows are unsteady flows. The vortices become more random and spread out as they move further downstream. Although the flow is predominantly turbulent, small laminar pockets or other remnants of laminar flow may still exist at specific points in the flow field, primarily where turbulence has not yet fully developed. The original smoke filaments introduced into the flow diffuse because of the turbulent mixing in this zone. As the flow transitions to a fully turbulent state, the smoke filaments lose their coherence, and the smoke rapidly spreads out because of increased diffusion caused by turbulent mixing.

Worked Example #2

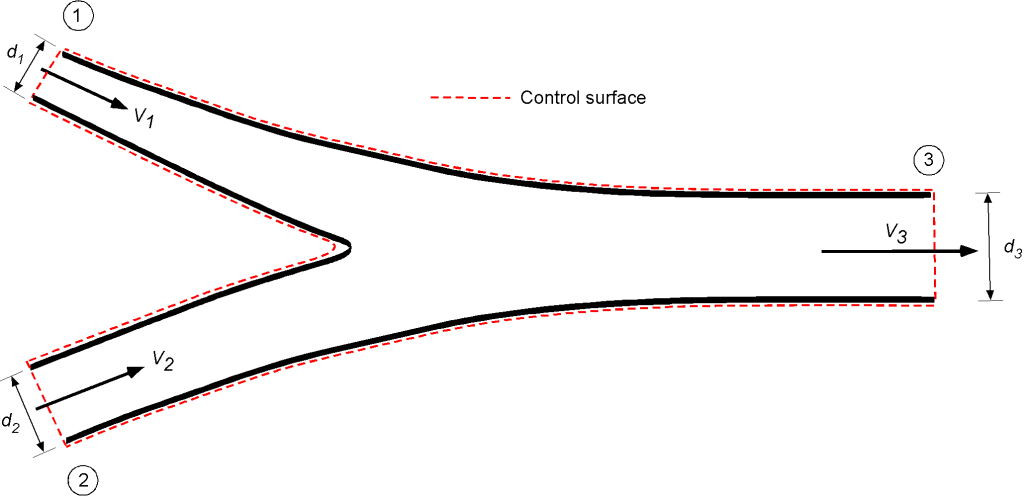

Two pipes with diameters and

converge to form a single pipe with diameter

. If a liquid flows with a velocity of

and

in the two pipes, respectively, what will be the flow velocity

in the third pipe? Hint: Assume steady, one-dimensional, incompressible flow with no losses.

In this case, two pipes merge to form a single pipe. Conserving mass and using average flow properties, then

If the fluid is a liquid then the assumption that =

=

=

= constant is justified so

Therefore, the flow velocity in the third pipe is

Worked Example #3

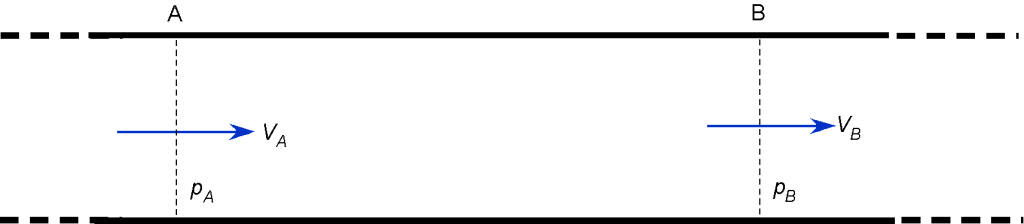

Air flows steadily through a horizontal pipe of a constant circular cross-sectional area. The air temperature is steady at C along the flow direction. At point A, the static pressure is

Pa, and the mean velocity is

m/s. At point B, the static pressure is

Pa. What is the average flow velocity at B? Use

= 287.057 J kg

K

and assume no losses.

The requirement for flow velocities suggests the use of the continuity equation, which can be written as

Notice that the density of the air is not given, but the pressures and the temperature are, so using the equation of state gives

Likewise

The use of the continuity equation gives

noting that

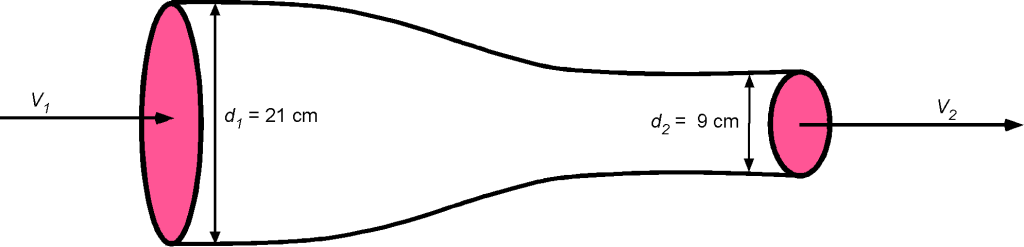

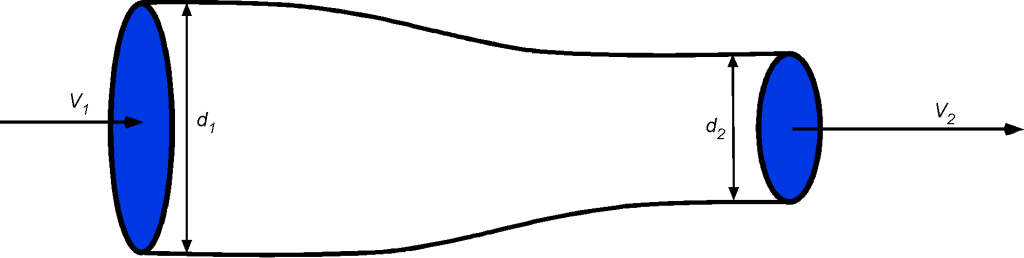

Worked Example #4

A gas of density 1.7 kg/m flows through a pipe with a volume flow rate of 0.12 m

/s. The pipe has an inlet section diameter of

of 21 cm and an outlet section diameter

of 9 cm. Assuming an ideal incompressible fluid flow, calculate the flow velocities at the pipe’s inlet and outlet, i.e.,

and

, respectively.

From the information given, assuming a one-dimensional, steady, incompressible, inviscid flow is reasonable. The flow rates, velocities, and Mach numbers are low enough that compressibility effects can be neglected. Let the inlet be condition 1 and the outlet condition 2. The continuity equation can be used to relate the inlet and outlet conditions, i.e.,

Or because the flow is assumed incompressible, then just

We see that

and

We can calculate , i.e.,

and also , i.e.,

so that

and

We have confirmed that the flow velocities are very low, much lower than a Mach number of 0.3, so the initial assumption of incompressible flow was justified.

Worked Example #5

A flowing liquid enters a pipe of diameter with a velocity

. What will the velocity

of the liquid be at the exit if the diameter of the pipe progressively reduces to

? Hint: Assume a one-dimensional ideal flow.

Conserving mass and using the continuity equation with average flow properties (i.e., one-dimensional flow) gives

Because the fluid is a liquid, the assumption that = constant is justified. So, the continuity equation is reduced to

In this case

where is the exit velocity. Rearranging gives

Worked Example #6

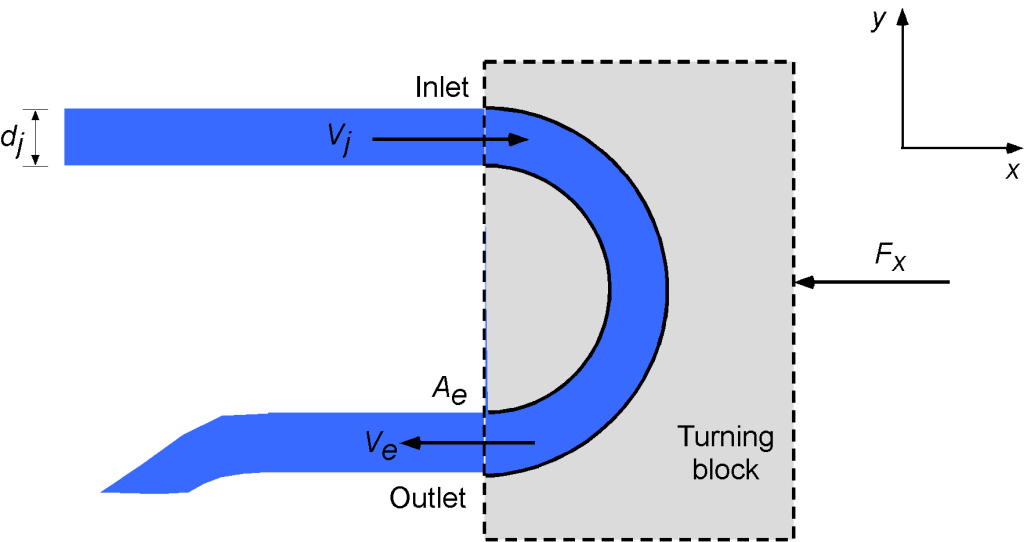

Consider the flow-turning block shown below. A circular jet of water with diameter 10 cm at a velocity

ms

enters the block. The block turns the water back through 180 degrees and then exits through an orifice with an area

of 120 cm

. First, find the velocity

of the water exiting the block. Second, determine the force

required to hold the block in place. Hint: Assume one-dimensional flow.

First, the conservation of mass is applied to the inlet and outlet flow from the control volume, i.e., for a steady flow.

and in one-dimensional form, then

or

The fluid is water so constant and so

Rearranging to solve for the exit velocity gives

Substituting the known values gives

Second, from the principle of conservation of momentum, then

where on the fluid from the block. In this case, then

The minus sign reminds us that the force on the fluid is to the left, i.e., in the negative direction. The mass flow rate is conserved, so

where the density of water has been assumed to be 1,000 kg/m, and so

Therefore, the reaction force on the block is to the right, i.e., in the positive direction. Therefore, the force to restrain the block will be 2196.6 N toward the left.

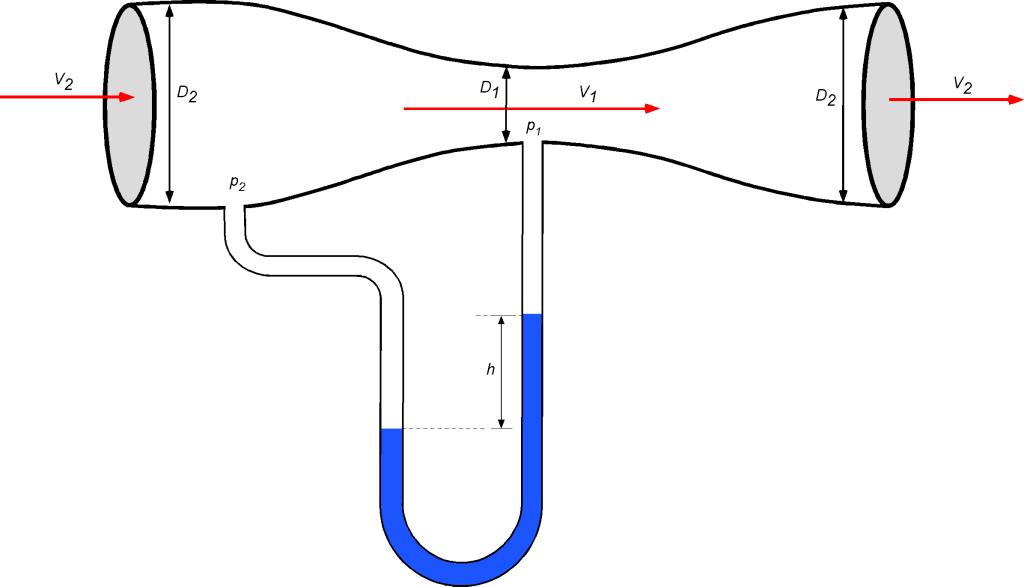

Worked Example #7

An incompressible gas flow in a pipe is passed through a venturimeter. The pipe diameter is = 4.1 inches, and the diameter of the throat of the venturimeter is

= 2.2 inches. The gas flow in the main pipe has a velocity

= 14.3 ft/s. If the static pressure difference between the venturi’s inlet and throat is measured using a U-tube water manometer, then calculate the height

between the two columns. Assume 1-dimensional flow and no losses. Also assume that

= 1.94 slug/ft

and

= 0.0023 slug/ft

.

Assuming steady, 1-dimensional flow, applying the continuity equation between the inlet and the throat gives

And because constant in this case (the flow is stated to be incompressible), then

Therefore, solving for gives

The application of Bernoulli’s equation gives

There is no change in the vertical height of the mean flow in this case, so and

Rearranging for the pressure difference gives

The U-tube manometer will measure this static pressure difference , so using the hydrostatic equation, the pressure difference is

making sure the density of water is used. Therefore, equating the latter two equations gives

and solving for leads to

Worked Example #8

For gases undergoing adiabatic compression or expansion, the bulk modulus is related to the pressure using . If changes in density in an incompressible flow must be less than 5\%, then show that to ensure incompressible behavior, the flow Mach number,

, must be less than 0.3. Hint: You may assume that

and

and

.

For gases undergoing adiabatic compression or expansion, the bulk modulus is given by

where is the ratio of specific heats. Using the result that

then substituting gives

Assuming as given in the question, then

Using into

gives

The speed of sound is given by

, so

. Substituting

gives

For incompressible behavior, changes in density must be less than 5\%, i.e.,

so that

Solving for gives

. Therefore, to ensure incompressible behavior in practical applications, the flow Mach number must be less than about 0.3.

Worked Example #9

If and

, is this a physically possible flow?

The flow will be physically possible if it satisfies the continuity equation, i.e., the divergence of the velocity field is zero. For a two-dimensional flow in the –

plane, then

In this case, and

, so

So, we have proved that this specific flow field is indeed physically possible.

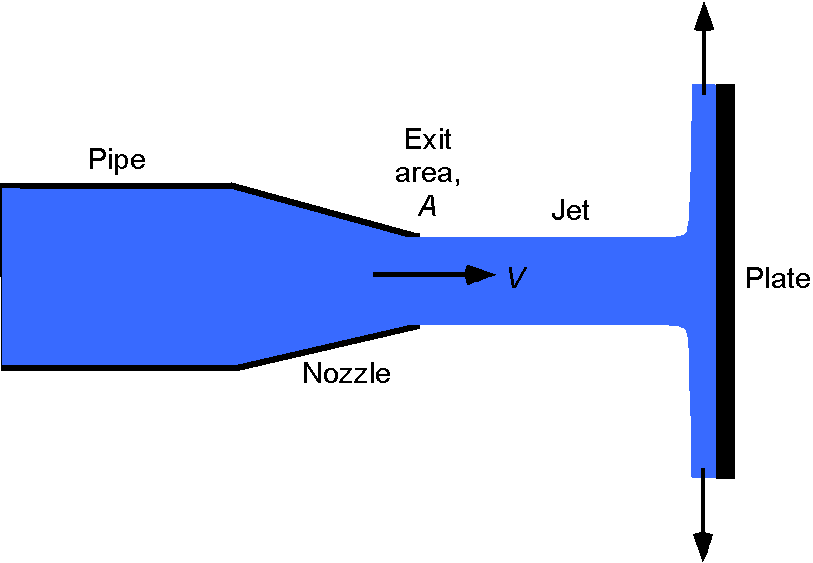

Worked Example #10

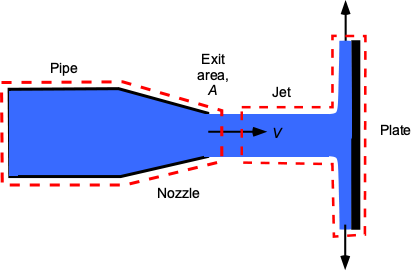

A water jet with velocity that exits from a nozzle strikes a vertical plate. The exit area of the nozzle is

. Find an expression for the horizontal force on the plate. If the volume flow rate through the nozzle is 0.5 m

s

and the diameter of the jet is 5 cm, then find the force on the plate in Newtons. The density of water can be assumed to be 1,000 kg m

.

Using a one-dimensional assumption, then

Using a one-dimensional assumption, then

The use of the continuity equation gives

And because we are dealing with water, it is incompressible, so

The value of is

Therefore, the force on the plate is

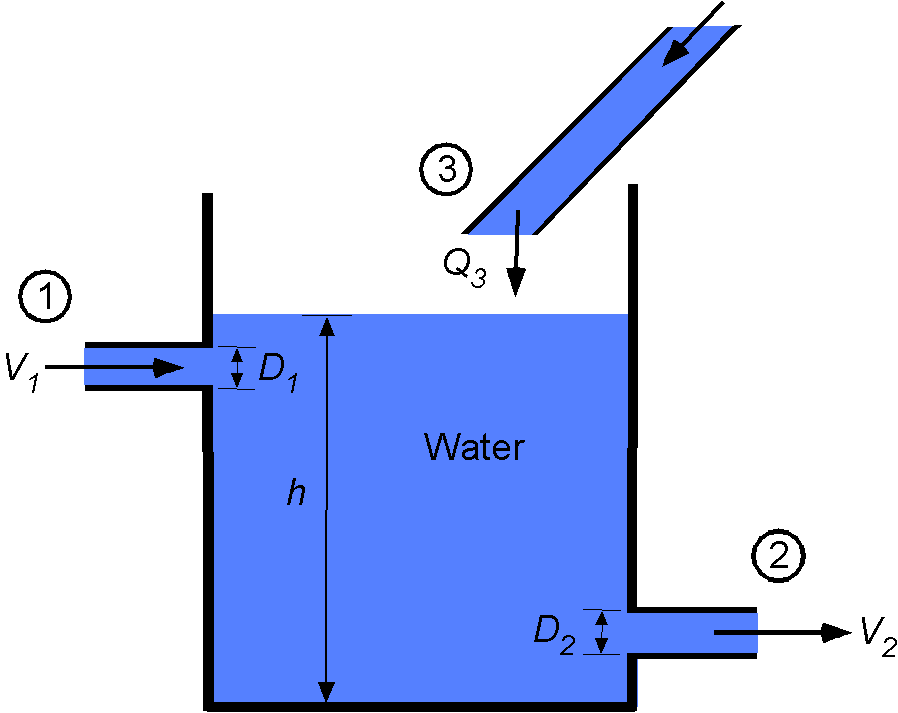

Worked Example #11

Water flows into a container through pipes 1 and 3 and simultaneously exits through pipe 2. The flow rates are adjusted such that the height of water in the container stays constant. The volume flow rate

m

/s and also

m/s,

m and

m. From this information, determine the value of

. Make any assumptions that may be justified.

If the level stays constant, then the system’s net mass (or volume) flow is constant in that the mass of water coming in per unit time is equal to the mass (or volume) of water leaving per unit time. In terms of the problem parameters, then

where m

/s. Remember that

so

and so

And solving for , which is what we are asked to find, then

We are given the diameters m and

m so

and

so

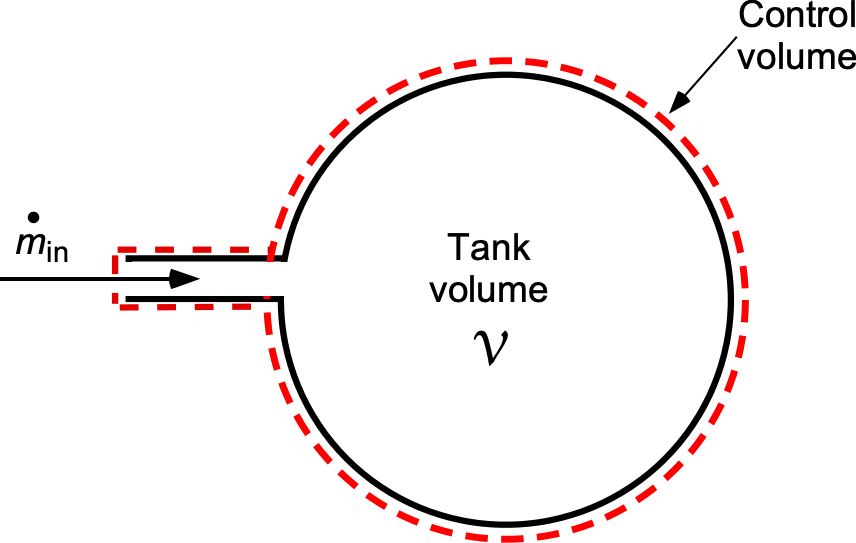

Worked Example #12

A rigid tank of volume has air pumped into it at a constant mass flow rate. Find the density and pressure in the tank as a function of time if the initial density and pressure are

and

, respectively. You may assume that the process is isothermal. Make any other assumptions that can be justified.

This is an unsteady flow problem because a mass of gas is pumped into a fixed volume, and for mass conservation, the gas density must increase in time. The general form of the continuity equation is

In this case

also

We will assume uniform mixing, and so the density inside the volume is uniform, so we have

Integrating using the separation of variables gives

so

which shows that the density of the gas increases linearly with time. The corresponding pressure can be obtained from the equation of state, i.e., . If the process is isothermal, then

, and so

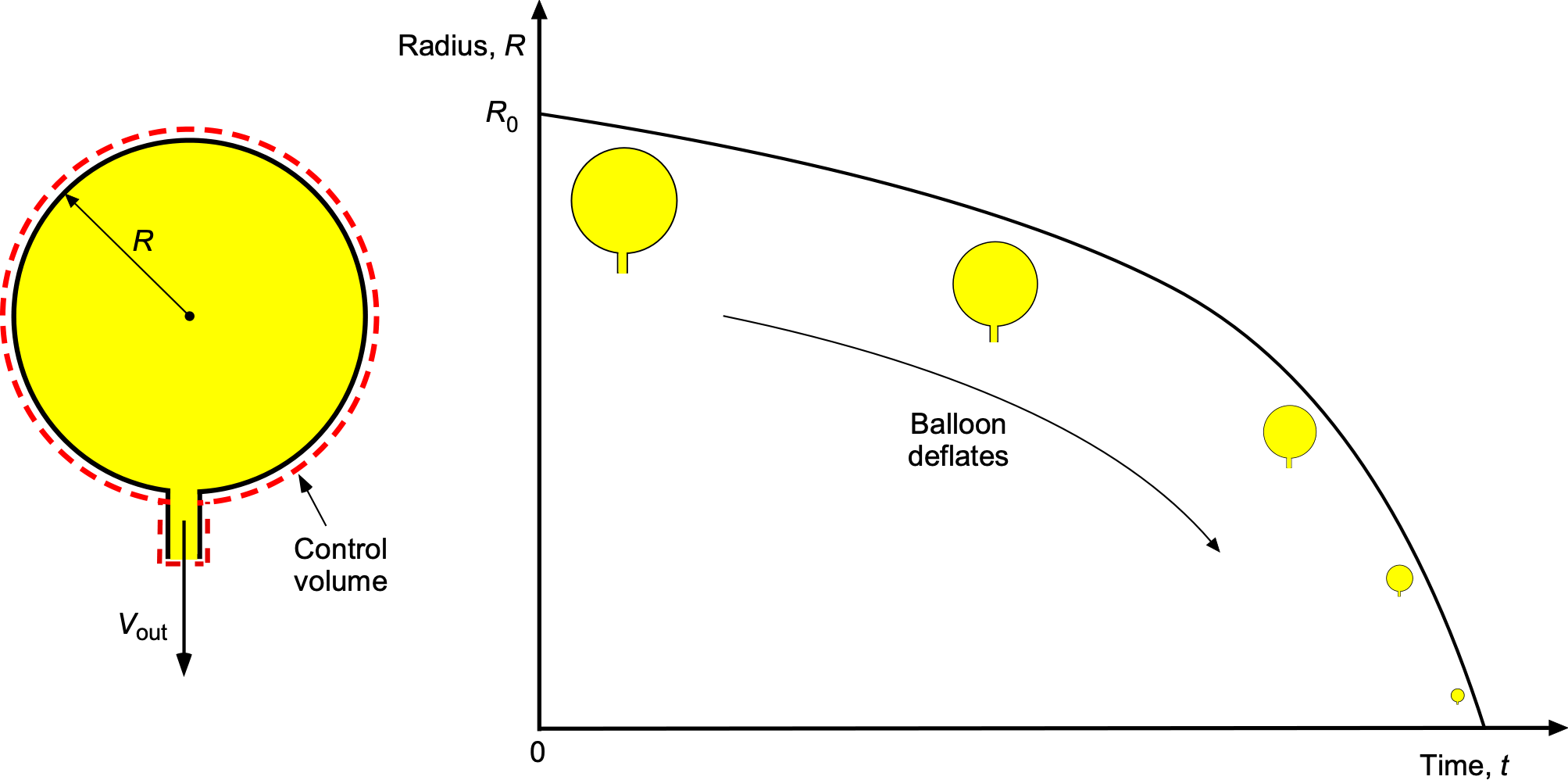

Worked Example #13

A spherical balloon of initial radius is filled with a gas of density

. The gas is at low pressure and can be assumed to be incompressible. The balloon starts deflating at time

through a small circular opening of diameter

. The velocity of the flow through the opening,

, can be assumed constant and one-dimensional. Assume the balloon is tethered so it does not fly away! Why would it do that anyway?

- Formulate the problem using the integral form of the continuity equation.

- Determine the rate at which the balloon’s radius changes with time.

For an incompressible gas, the continuity equation in integral form is

The volume of the balloon at any time is

Taking the time derivative

The outflow mass flow rate through the opening of diameter is

where is the flow velocity through the opening.

Using the continuity equation gives

The flow is incompressible, so

Rearranging gives

and so

Separating variables and integrating gives

The solution is

The boundary condition is give as ,

, so

Rearranging and simplifying gives

Therefore, the solution for the radius of the balloon as a function of time is

Worked Example #14

Identify and explain each term starting from the most general form of the continuity equation. Then, show and explain carefully how both of these general equations can be simplified for application to problems that involve: (a) steady, compressible flows, (b) incompressible flows, and (c) inviscid, one-dimensional, steady flows.

The general form of the continuity equation is

The first term represents the time rate of change of fluid mass within the control volume, and the second term is the net mass flow rate of fluid out of the control volume. Conservation of mass requires that the net sum be zero.

(a) Steady, compressible flow. In this case so that

which is a statement that an equal mass of fluid coming into a control volume per unit time will also leave the control volume simultaneously.

(b) Steady, incompressible flow. In this case, = constant so that we can write

This is a statement that the volume flow rate is conserved, i.e., an equal volume of fluid coming into a control volume per unit time will leave the control volume simultaneously.

(c) One-dimensional, steady flow. In this case, we must again retain the density in the integral, but if the flow is one-dimensional, then the flow properties can change only in one dimension, so for a fixed control volume with an inlet and outlet plane defined accordingly, by conserving mass, we would end up with

or

This is a common form of the continuity equation, which is very useful for problem-solving when average flow properties are required.

Worked Example #15

Starting from the most general form of the momentum equation, identify the meaning of each of the terms and show how the equation can then be simplified for application to problems involving: (a) Steady flows, (b) Steady, incompressible flows, (c) Steady, inviscid flow. (d) Unsteady flows with no body forces. In each case, explain the physical meaning of the terms in the respective equations.

The most general form of the momentum equation in integral form is

In words: Body Forces + Pressure Forces + Viscous Forces = Time rate of change of momentum inside from unsteadiness + Net flow of momentum out of

per unit time. It is a vector equation, so three scalar equations are rolled into one. This equation is very general and will apply to any flow.

(a) For steady flows, then , and the reduced form of the momentum equation will be

(b) For steady, incompressible flows then and

constant so

(c) For steady, inviscid flow then and

so

(d) For unsteady flows with no body forces, then = 0, so

Worked Example #16

Starting from the most general form of the energy equation, identify the meaning of each of the terms and show how the equation can be simplified for application to problems involving: (a) Steady flows, (b) Steady, inviscid flow, (c) Steady flows with no body forces, heat, or work addition. In each case, explain the physical meaning of the terms in the respective equations.

The most general form of the energy equation is

which is a statement of energy conservation for a fluid. While this is a very general equation, there are many practical problems in which we can simplify it, i.e., by making certain justifiable assumptions, which commensurately makes the mathematics and solution process easier.

(a) In the case of a steady flow, then , so

(b) In the case of a steady, inviscid flow, then and all of the terms that have their origin in the viscosity of the fluid can be neglected, i.e.,

(c) In the case of a steady flow with no body forces, heat, or work addition, then

Worked Example #17

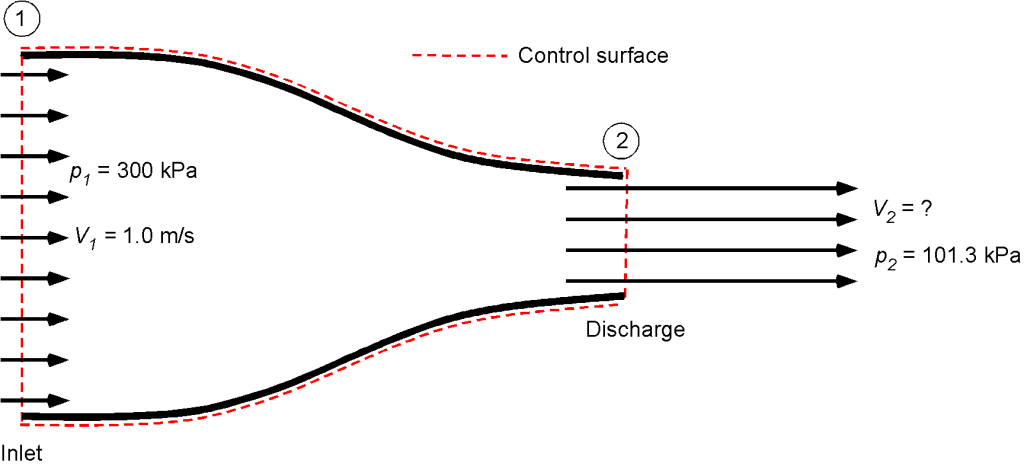

Water ( = 1,000 kg/m

) flows in a pipe with a velocity of 1.0 m/s and a pressure of 300 kPa. At a nozzle, a shape often referred to as a contraction, the pressure decreases at the outlet (discharge) to atmospheric pressure (101.3 kPa), as shown in the figure below. There is no change in height. Use the Bernoulli equation to calculate the velocity of the water as it exits the nozzle.

Using the Bernoulli equation ( constant) then

Rearranging to solve for gives

Worked Example #18

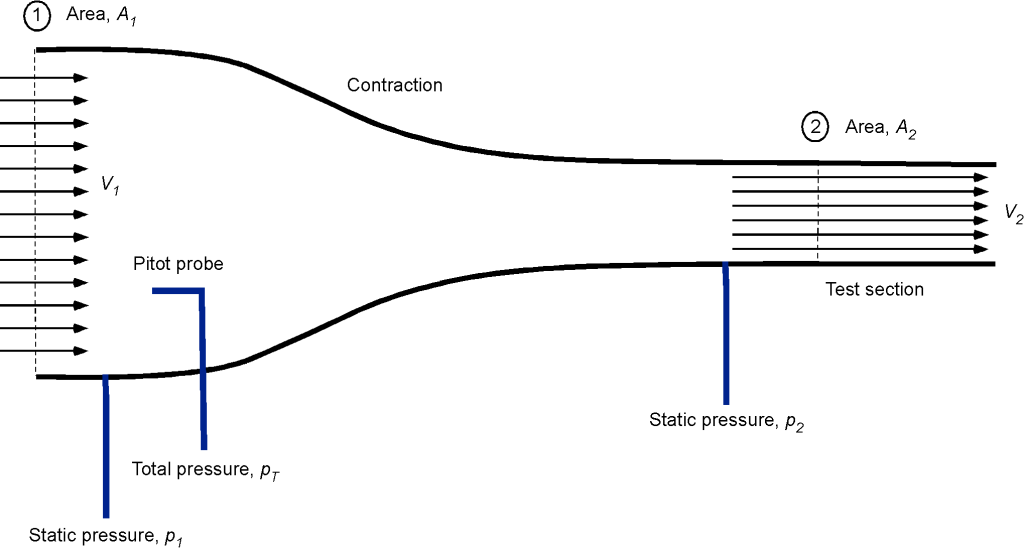

The airflow into a wind tunnel test section first passes through an upstream contraction section and then exhausts through a diffuser. Show by using the conservation equations that the flow velocity in the test section can be determined (calculated) by using the following:

(a) The difference between the total pressure in the opening (mouth) of the contraction section and the static pressure at the inlet to the test section.

(b) The difference in static pressure between the mouth of the contraction section and the static pressure at the inlet to the test section.

In each case, derive an equation relating the flow velocity in the test section to the pressure drop and the cross-sectional areas of the inlet and test sections.

The working part of a wind tunnel is a venturi. The airflow at the settling chamber (i.e., the mouth of the venturi) of area can be assumed to have a flow velocity

with static pressure

. The wind tunnel cross-section then contracts to a smaller area

at the test section where the velocity has increased to

, and the static pressure has decreased to

. Notice that the velocity must increase if continuity (conservation of mass) is to be satisfied. A model (such as a wing or complete airplane model) is tested in the test section, and the aerodynamic characteristics are measured. The flow then passes downstream into a diverging duct, known as a diffuser.

First approach: From the continuity equation, the flow velocity in the test section will be

The pressures at the inlet (i.e., settling chamber) and the test section of the wind tunnel can be related to the flow velocities using Bernoulli’s equation, i.e.,

where is the total pressure. This means that

Therefore, the preceding equation can be used to determine the velocity in the test section from a measurement of total pressure measured in the contraction section (using a Pitot probe) and the static pressure at the test section (using static pressure taps). However, the density of the air must be known by measuring the temperature and pressure of the air in the flow and then calculating the density using the equation of state. This technique is used in many low-speed wind tunnels to measure the flow speed in the test section.

Second approach: From the continuity equation, the flow velocity in the test section will be

The static pressures at the inlet (i.e., settling chamber) and the test section of the wind tunnel can be related to the flow velocities using Bernoulli’s equation, i.e.,

The velocity in the test section can be related to the static pressure drop across sections 1 and 2, i.e., the pressure drops between the contraction and test sections. From the Bernoulli equation, we have

This means that

Solving for (the flow velocity in the test section), we obtain

In the second case, the area ratio must be known; however, this is easily measured and remains constant for a given wind tunnel. Again, the density of the air must be known, which is determined by measuring the temperature (using a thermocouple) and pressure (using a pressure transducer) of the air in the flow, and then calculating the density using the equation of state. This technique is also used in low-speed wind tunnels to determine the flow speed in the test section, although it is a less common approach because, in practice, it is a little less accurate than the first method. The reason is that the static pressure drop

is much smaller than the difference between

, so it is more difficult to accurately measure using a pressure transducer.

Worked Example #19

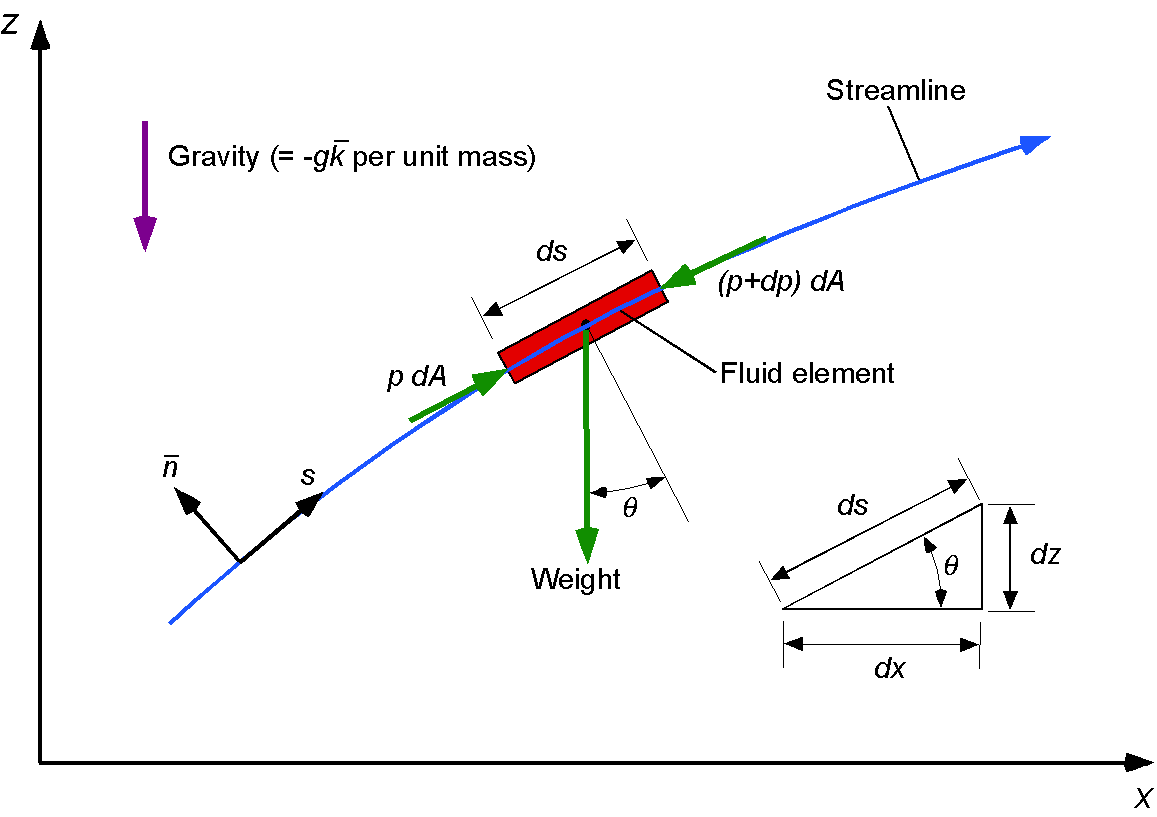

Consider the steady flow of a fluid element along a streamline, as shown in the figure below. By determining the net forces on the fluid element, show how the Bernoulli equation can be derived using Newton’s second law. Notice that is measured along the direction of the streamline.

The forces acting on the fluid element in the -direction are the pressure and the component of the element’s weight,

. Therefore, the net force on the element,

, is

The weight of the element, , is

Therefore,

The acceleration of the fluid element is

where is the velocity of the fluid element along the streamline. Therefore, using Newton’s second law, then

or

noting that . After rearrangement, then

Dividing through by gives

or

Finally, after integration, then

which again is the Bernoulli equation.

Worked Example #20

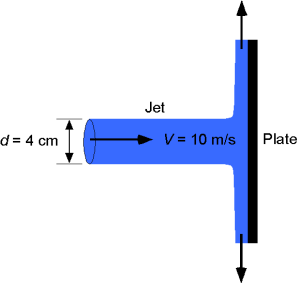

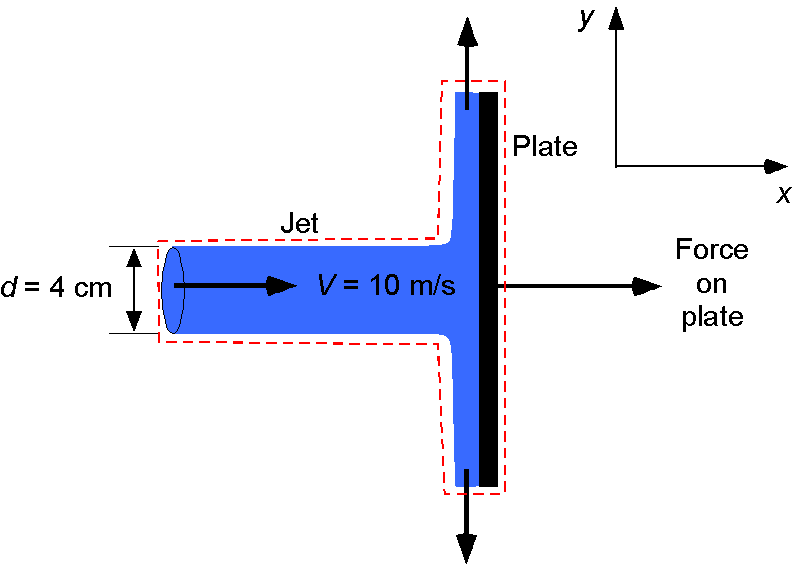

A horizontal water jet with a diameter = 4 cm impacts a vertical plate at a velocity of 10 m/s. Draw an appropriate sketch and control volume to analyze this problem. Using the conservation laws of fluid dynamics, find the force on the plate,

. Make a one-dimensional, steady flow assumption.

The mass flow rate in the jet is

where = 10 m/s and

= 0.00126 m

.

The horizontal jet impacts the plate and comes to rest horizontally. To do this, the force on the fluid has to be equal to the time rate of change of momentum in that direction, and the force on the plate is in the opposite direction, i.e.,

Substituting the numerical values gives

Worked Example #21

An incompressible gas flow in an exhaust system encounters a change in the size of the exhaust pipe as it transitions to the muffler. The exit diameter of the muffler pipe is = 4.1 inches, and the diameter of the inlet header pipe is

= 2.2 inches. The exhaust gas is discharged at a speed of

= 14.3 ft/s. If the static pressure difference between the header and the muffler is measured using a U-tube water manometer, then calculate the height

between the two columns. Assume 1-dimensional flow and no losses. Also assume that

slug/ft

and

slug/ft

.

Assuming steady, 1-dimensional flow, applying the continuity equation between the inlet (section 1) and the exit (section 2) gives

And because constant in this case (the flow is stated to be incompressible), then

Therefore, solving for the inlet velocity gives

The application of Bernoulli’s equation gives

There is no change in the vertical height of the mean flow in this case, so and

Rearranging for the pressure difference gives

The U-tube manometer, as shown, will measure this static pressure difference , so using the hydrostatic equation, the pressure difference is

making sure we use the density of water here. Therefore, equating the latter two equations gives

and solving for leads to

Worked Example #22

Gas flows at speed through a horizontal section of pipe whose cross-sectional area is

m

. The gas has a density of

kg/m

. A Venturi meter with a cross-sectional area of

m

has been substituted for a section of the larger pipe. The pressure difference between the two sections is

Pa. Find: (a) Find the speed

of the gas in the original pipe. (b) Find the speed

in the throat of the venturi. (c) Find the volume flow rate

.

(a) We are told the gas has a density of 1.34 kg/m, implying constant density so that the Bernoulli equation can be used, i.e.,

We can assume from the figure that both pressure gauges are at the same height, so , and the Bernoulli equation is now

The continuity equation (constant density gas) is

so

The Bernoulli equation becomes

We are given that m

and

m

so

becomes

(b) Using the continuity equation, then

(c) The volume flow rate is

so we get

Worked Example #23

Water ( = 1,000 kg/m

) flows in a hose with a velocity of 1.0 m/s and a pressure of 300 kPa. At the nozzle, the pressure decreases to atmospheric (101.3 kPa). There is no change in height. (a) Use the Bernoulli equation to calculate the velocity of the water as it exits the nozzle. (b) The hose ejects the water stream through the nozzle with a final diameter of 3 cm. The stream is then directed onto a stationary wall. Determine the force on the wall from the stream.

(a) We are told to use the Bernoulli equation ( constant), which is

Rearranging to solve for gives

(b) The need for a force suggests using the momentum equation. The momentum of the jet before the wall is where

When the jet hits the wall, it is brought to rest in the horizontal direction (it will be deflected in all other directions)

where is the force. Solving for

gives

Worked Example #24

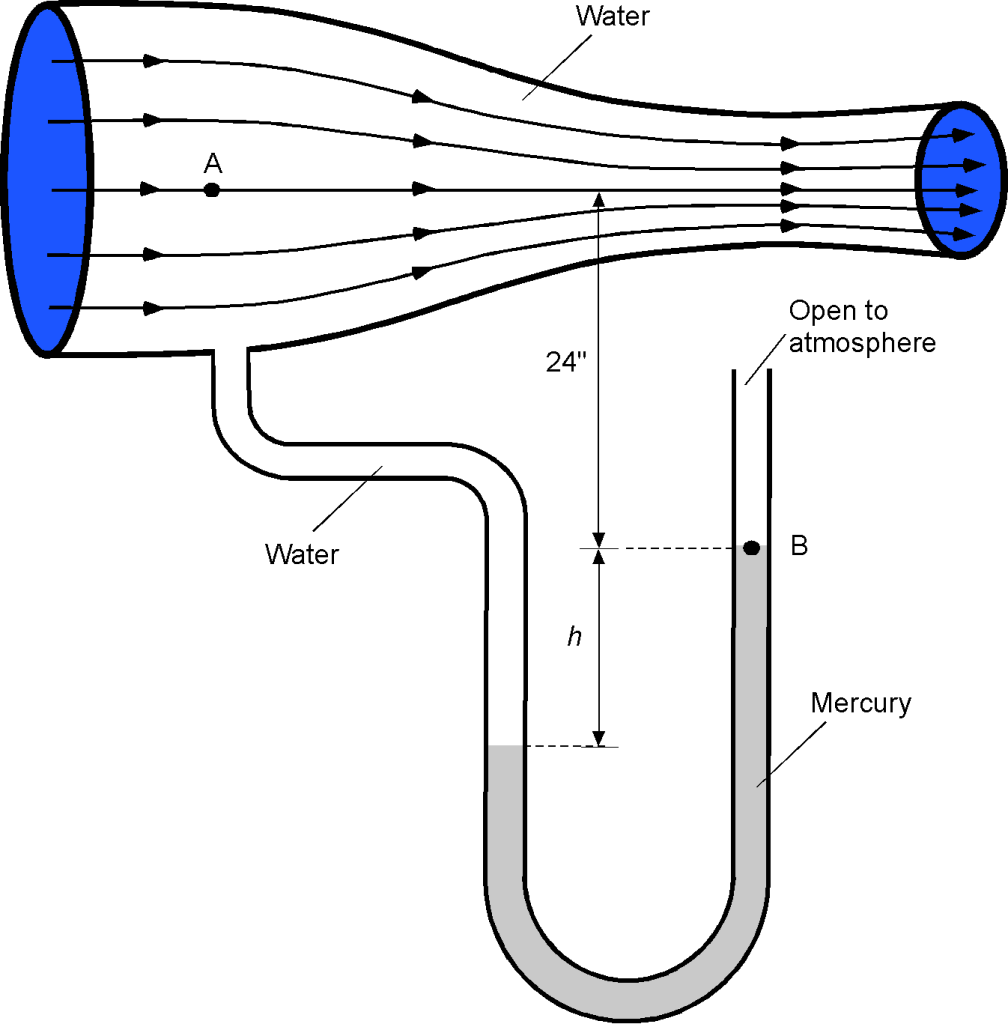

Water flows through a converging nozzle. If the pressure at point A at the intake to the nozzle is 19.7 lb/in, then determine the height

shown on the U-tube manometer. Notes: Assume atmospheric pressure

is 14.7 lb/in

. The density of water can be assumed to be 1.93 slugs/ft

, and the specific gravity of mercury is 13.6.

Let the height from point A to point B be . Let

be the height from the bottom of the U-tube to the lowest point of the mercury. Considering the left leg of the U-tube, the pressure at the lowest point in the U-tube will be

For the right leg, the pressure at the same point will be

Equating these latter two equations gives

and rearranging gives

Solving for gives

Now, we can substitute the information given. Notice that = 5 lb/in

= (5

144) lb/ft

= 720.0 lb/ft

. Therefore,

Worked Example #25

Water flows through a pipe with a circular cross-section and a volume flow rate of 14.2 ft/s, encountering a change in the area and height of the pipe as it passes through an elbow-type coupling. The exit area of the pipe is

= 2.4 ft

, and the area of the inlet is

= 4.8 ft

. Assume 1-dimensional flow and no losses with

slug/ft

. (a) Determine the flow velocities at the entrance (

) and the exit (

) in units of ft/s. (b) If

= 6 inches and

= 25 inches, what is the static pressure difference between the inlet and outlet, i.e., the value of

, in units of lb/in

?

(a) The fluid is water, so it is incompressible. The application of the continuity equation in one-dimensional form gives

Therefore, the inlet flow velocity is

and for the outlet flow velocity , then we know that

so

It will also be noted that

(b) The Bernoulli equation is

so, in this case

We are asked for the pressure difference , so using the Bernoulli equation gives

and substituting the known values gives

Notice that it is necessary to convert the hydrostatic head (last term) from units of inches to feet to keep the entire equation in consistent base units of lb, ft, and seconds (s). Evaluating the arithmetic gives

noting that 144 lb/in is equal to 1 lb/ft

.

Worked Example #26

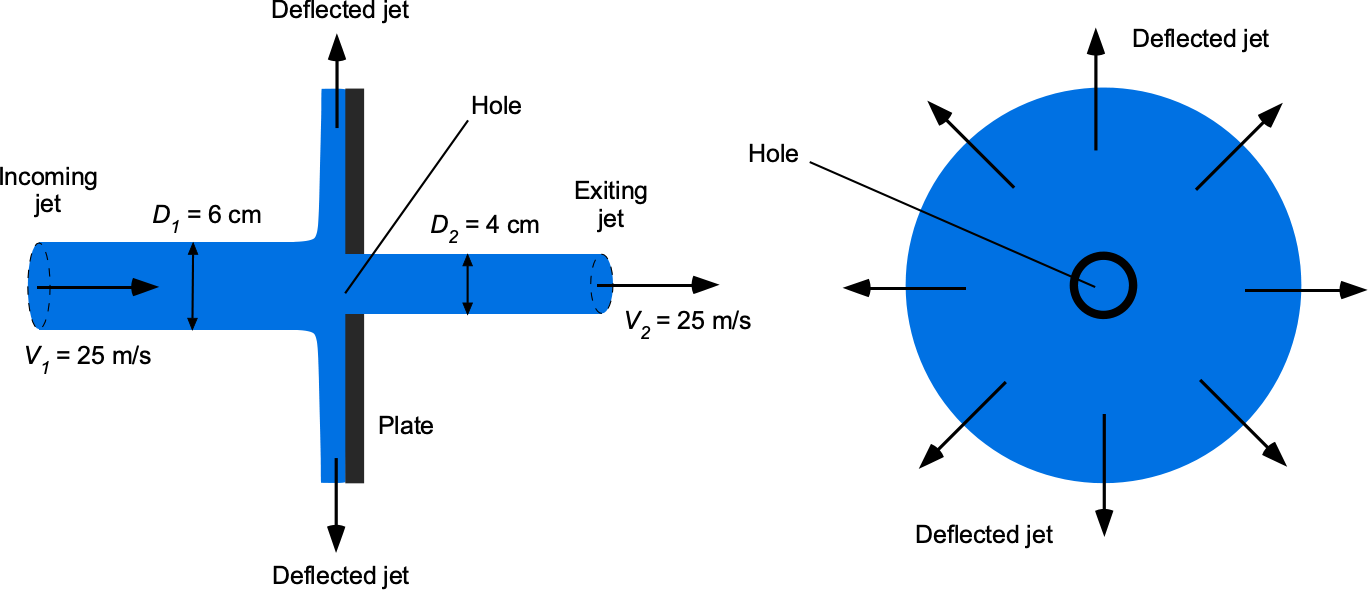

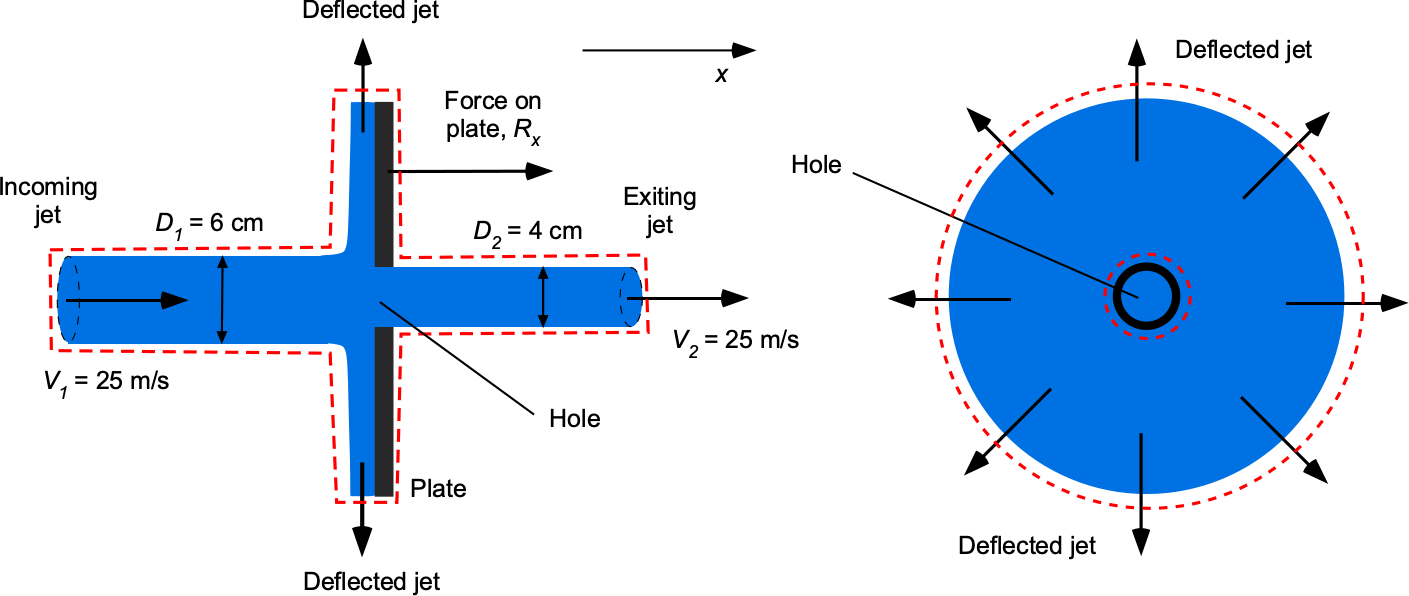

As shown in the figure below, a 6 cm diameter water jet strikes a circular flat plate containing a hole with a diameter of 4 cm. Part of the jet passes through the hole, and the other part is deflected radially symmetrically away from the plate. The density of water can be assumed to be 998.23 kg m. (a) Calculate the mass flow rate of the jet toward the plate. (b) Calculate the mass flow rate of the jet’s deflected part. (c) Determine the magnitude and direction of the force required to hold the plate stationary.

(a) Valid assumptions are incompressible, steady, no body force, inviscid, and one-dimensional flow across any given cross-section. The control surface is shown in the figure below.

The mass flow rate of the jet toward the plate is

and inserting the values gives

(b) Conservation of mass in the one-dimensional form gives

with the minus sign on the first term indicating that the flow is inward and in the opposite direction to the outward-pointing surface normal vector. In terms of mass flow rates, then

Therefore, the radially deflected mass flow rate is

Inserting the numerical values gives

(c) The entire system is subjected to a background (atmospheric) pressure, so no net pressure force is acting on the control volume. The force on the fluid (to change its momentum) is found from the conservation of momentum. Only the the part of the mass flow is deflected, so

It is unnecessary to determine the radial velocity. Inserting the numbers gives

Therefore, the force applied to the plate by the water jet is

A force of N is required to hold the plate stationary, indicating that the force acts to the left.

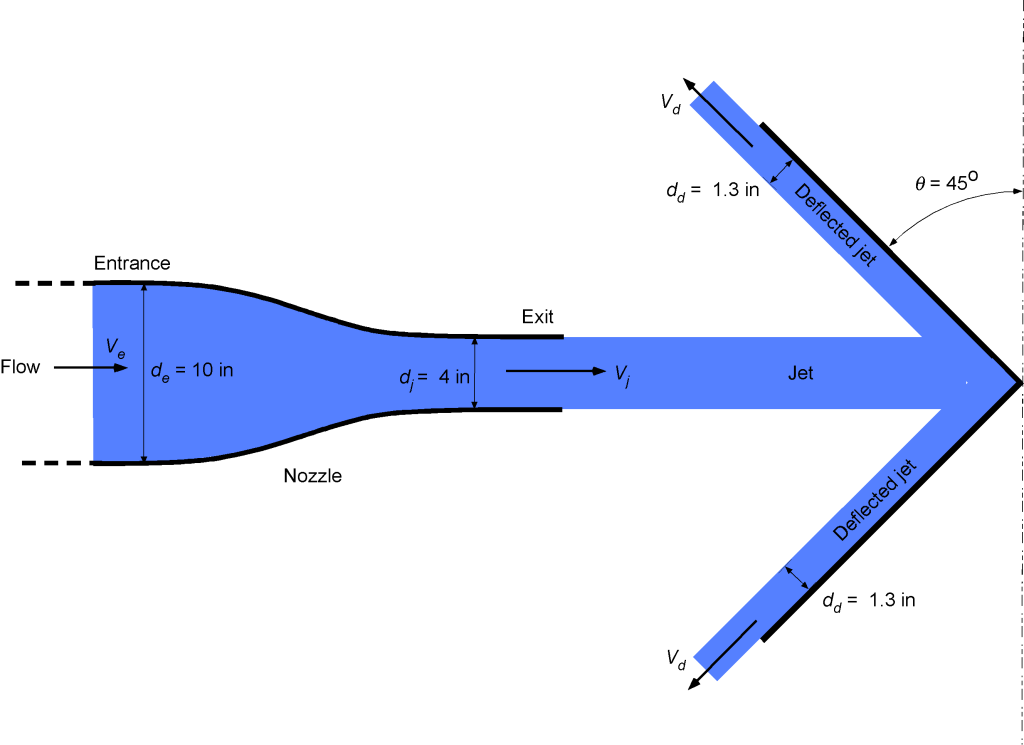

Worked Example #27

Two plates, set 4 cm apart, are separated by an oil bed. The bottom plate is stationary, but the top plate moves at a speed of 3.5 m/s. Calculate the shear stress in the oil. Assume that the oil’s dynamic viscosity coefficient is 583.95 Pa s. Note: A Pascal-second (Pa s) is the SI dimensions of viscosity and is equivalent to Newton-second per square meter (N s m), which is sometimes referred to as the Poiseuille (Pl).

It is necessary to calculate the shear stress in a fluid, , based on the formation of a velocity gradient. The use of Newton’s formula of viscosity gives

Newtonian flow will give a constant uniform velocity gradient, in this case, between the upper and lower plates will be

This means that the shear stress per unit depth in the fluid will be

Worked Example #28

Water ( = 1.94 slug ft

) flows at a mass flow rate of

= 6.0 slug s

through a nozzle with an entrance diameter

in and and exit diameter of

. The water hits an angled bracket, as shown in the figure below, such that exactly half of the mass flow rate of the stream deflects to the left and half deflects to the right. The diameter of the deflected jets,

, is 1.3 in. Assume that the water remains in a horizontal plane and is a one-dimensional flow.

Calculate the following:

- The velocity of the water entering and exiting the nozzle,

and

.

- The change in pressure

between the nozzle entrance and its exit.

- The velocity

of the water in the deflected jets.

- The magnitude and direction of the force on the bracket.

1. The velocity of the water entering and exiting the nozzle can be determined using conservation of mass (continuity equation), i.e.,

The entrance area is

The entrance velocity is

and substituting the values gives

The exit jet area is

The exit jet velocity is

and substituting the values gives

2. The change in pressure between the nozzle inlet and its exit can be found using the Bernoulli equation, i.e.,

In this case, then

We are asked for a change in pressure, so

and substituting the values gives

3. The velocity of the water in the deflected jet can be determined using the continuity principle. In this case, half of the mass flow is deflected in each direction, so

The deflected jet area is

The deflected jet velocity is

and substituting the values gives

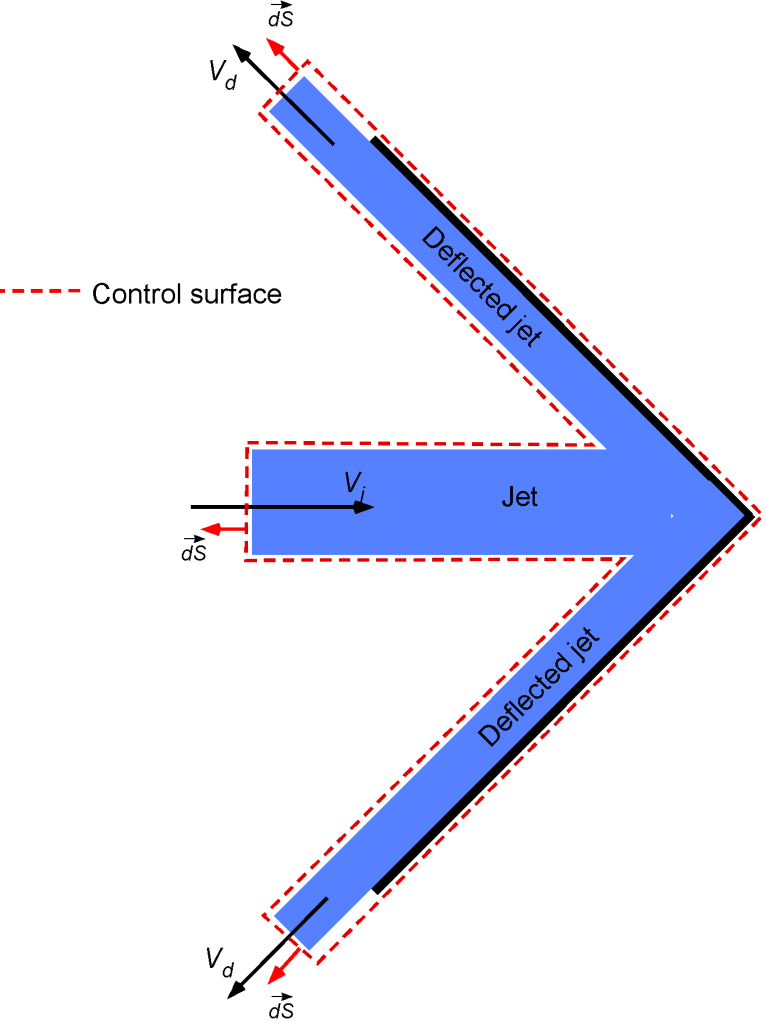

4. The force exerted by the plate on the water can be determined from the time rate of change of momentum of the fluid, as shown in the following control volume. To this end, the rate of momentum of the water coming onto the deflector in the downstream (horizontal) direction is . Likewise, the rate of deflected momentum coming out away from the defector is

. Notice that the

term gives the correct horizontal momentum component.

Therefore, the force on the plate will be the time rate of the net momentum, so that

Inserting the numbers gives

which will be applied by the water in the downstream direction, away from the nozzle

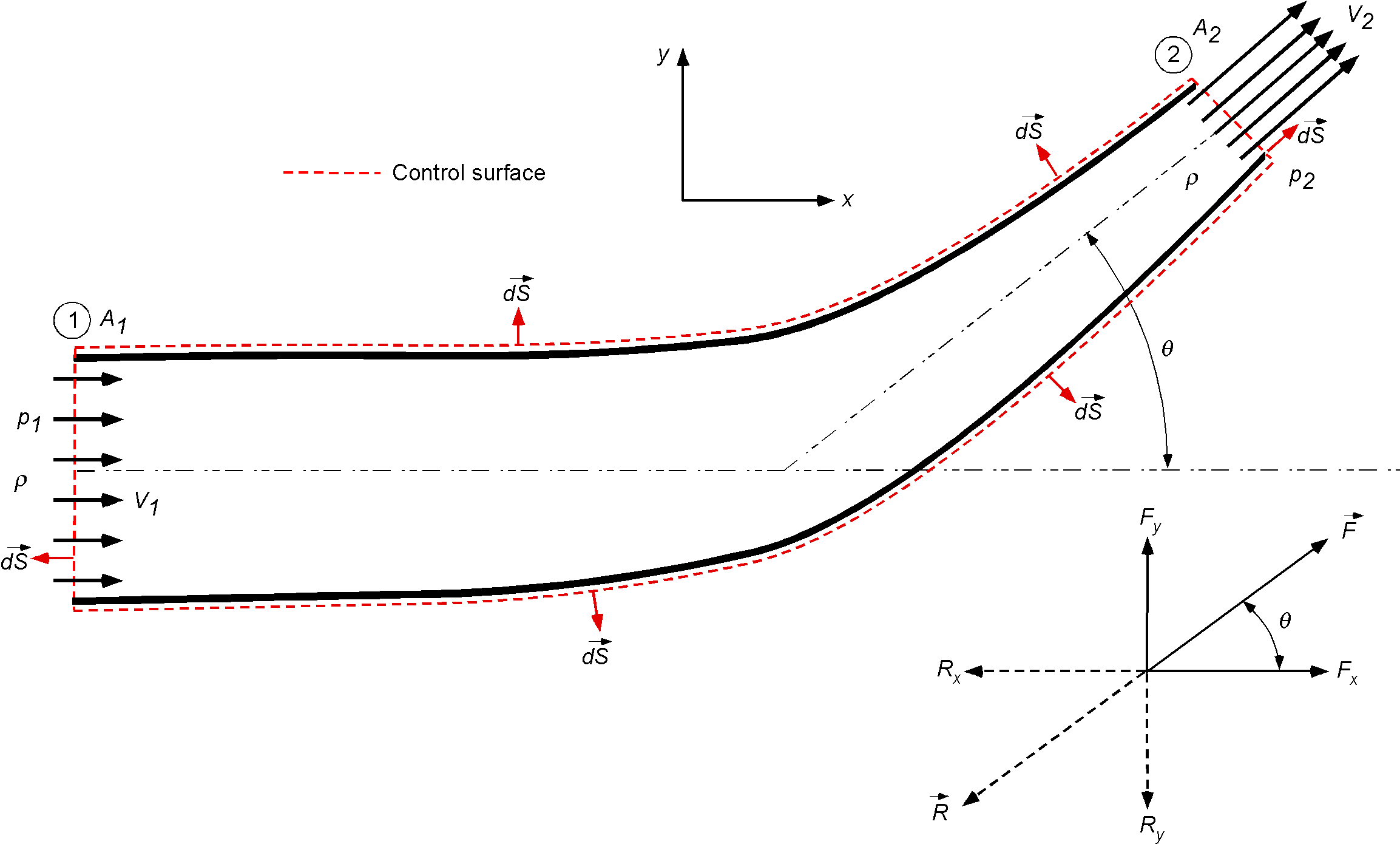

Worked Example #29

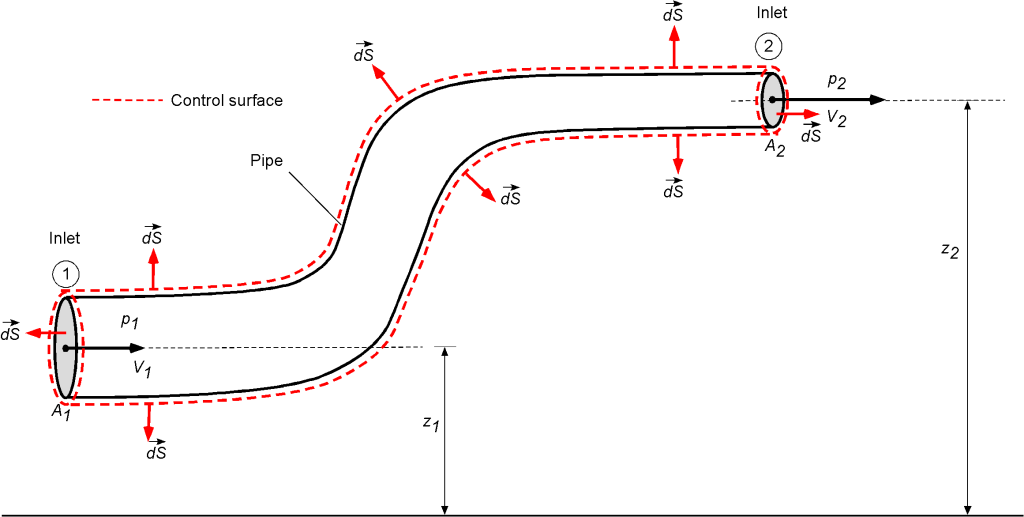

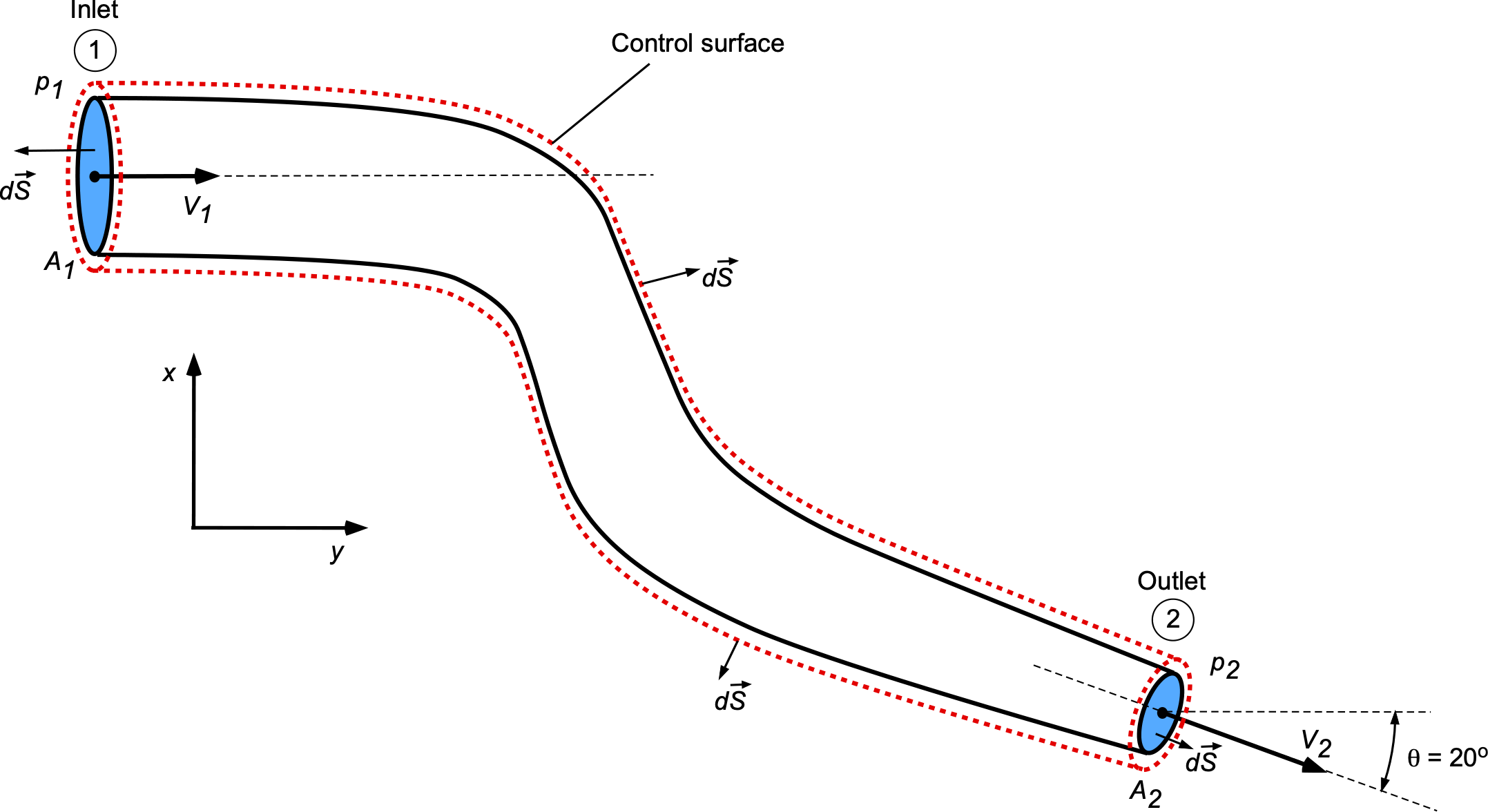

Consider the steady flow of a liquid through an elbow-shaped converging axisymmetric pipe joint with an inlet area and outlet area

, as shown in the figure below. The volumetric flow rate is

. The elbow angle is

in a horizontal plane. Assume that the flow inside the pipe is one-dimensional. Use the continuity and momentum equations to set up the procedure to find the resultant force on the pipe. Note: You do not have to find the force; show how to use and set up the relevant equations.

The flow is steady, so , and the flow can be assumed as inviscid, so

. The fluid is a liquid (which has a relatively high density), but there is no change in elevation from one side of the nozzle to the other. Therefore, gravitational effects can be neglected.

The general form of the momentum equation is

and the reduced form for the assumptions made in this question leads to

The pressure integral on the left-hand side can be written as

In this case, the force of the walls on the fluid, say (to change its momentum), needs to be determined, i.e., this is the unknown. There is also an equal and opposite force on the nozzle, denoted as

, which ultimately needs to be determined.

We are instructed to assume one-dimensional flow over the cross-section of the nozzle; however, the flow in this case moves in two directions, and

. Therefore, two scalar momentum equations will be in the

and

directions, respectively. In general form, the momentum equation is

With the one-dimensional assumption, for the direction, then

so that

For the momentum equation in the direction, then

so that

We are not asked to move forward from this point; we are only asked to set up the equations to be solved. In summary, these are

and

We also have the continuity equation to round out the other two equations, i.e.,

Worked Example #30

Water flows through a pipe with a circular cross-section and encounters a change in the area of the pipe as it passes through an elbow-type coupling, as shown in the figure below. The pipe is in a horizontal plane, i.e., the –

plane. The volume flow rate is 13.4 ft

/s. The exit area of the pipe is

= 2.1 ft

, and the area of the inlet is

= 4.8 ft

. Assume uniform flow properties across any cross-section and no losses. For water,

slug/ft

.

- Determine the entrance velocity (

) and the exit velocity (

) in units of ft/s.

- What is the static pressure difference between the outlet and inlet, i.e., the value of

, in units of lb/in

?

- Determine the equation(s) for the force on the pipe.

1. The flow rate and the input and output areas are given, so

and

2. The Bernoulli equation is

The flow is in the –

plane so there is no hydrostatic head, i.e.,

, so

Rearranging to solve for the static pressure difference between the inlet and outlet gives

Substituting the known values gives

We are asked for the pressure in units of lb/in, so

3. The force on the pipe can be obtained by assessing the net pressure forces and the time rate of change of momentum. The momentum equation in terms of the two scalar components will be

and

where and

are the forces on the fluid in the

and

directions, respectively.

Rearranging the -momentum equation gives

and for , then

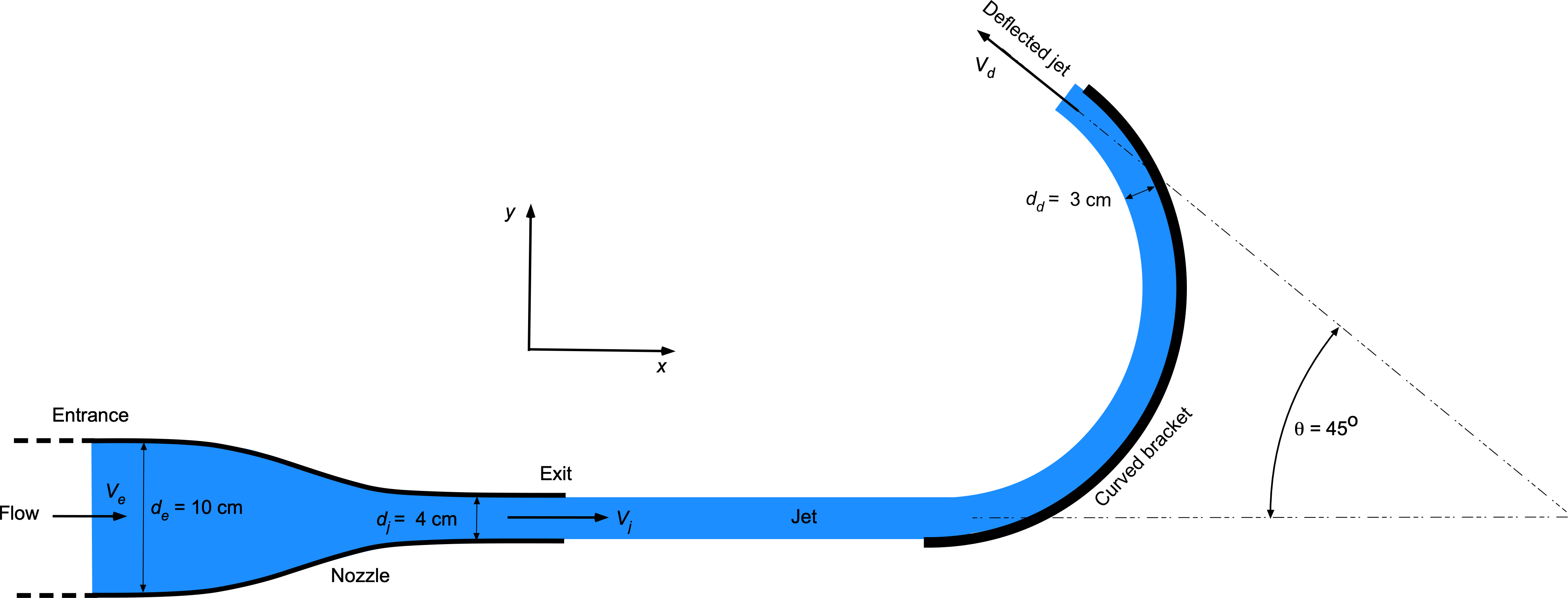

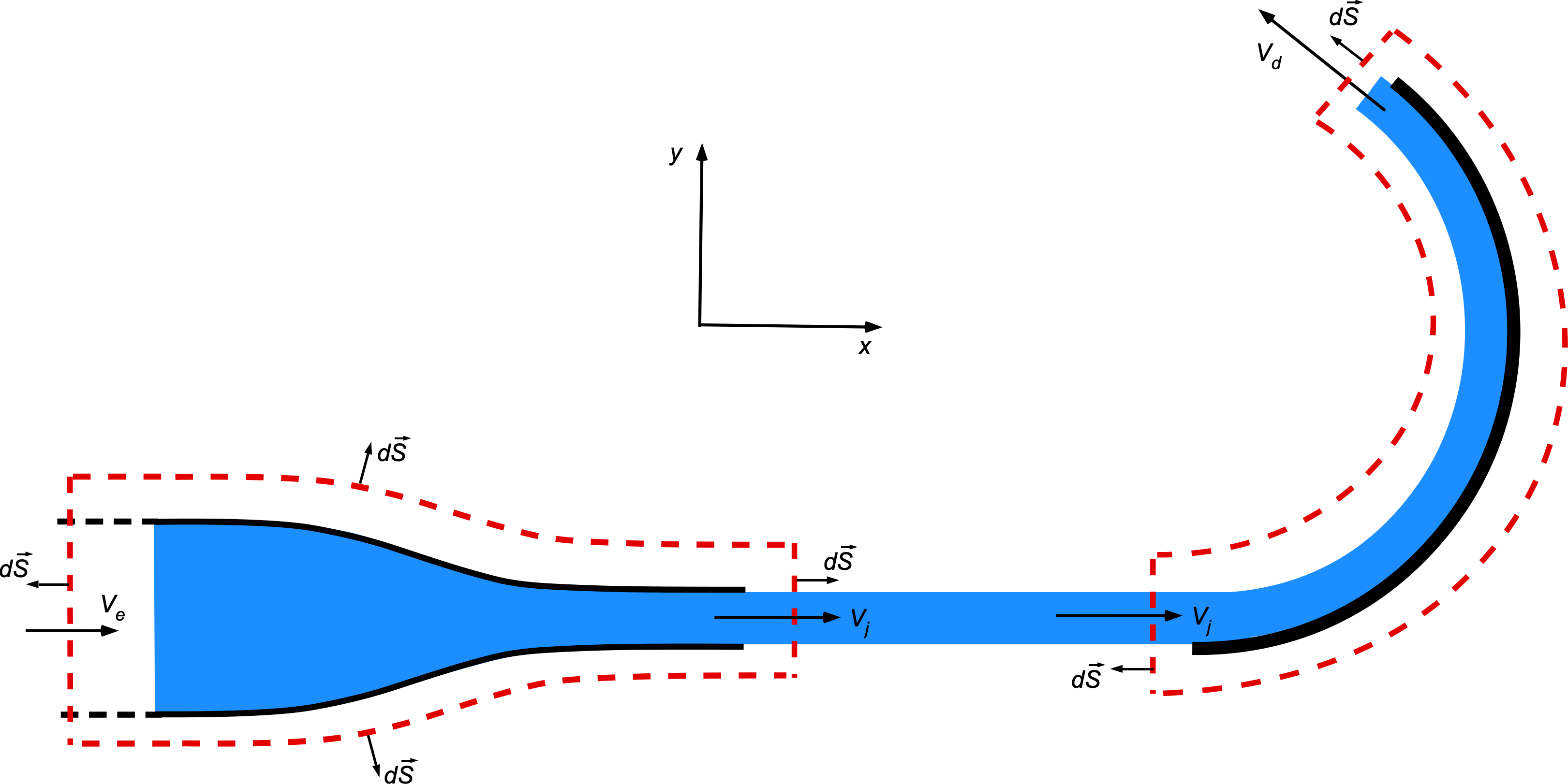

Worked Example #31

Water () flows at a mass flow rate of

through a nozzle with an entrance diameter

and an exit diameter

. The water then hits a curved bracket, as shown in the figure below. The diameter of the deflected jet is

. Assume the water remains in a horizontal plane and flows one-dimensionally.

- Draw an appropriate control surface with annotations to analyze the problem.

- Calculate the velocity of the water entering and exiting the nozzle (

and

).

- Calculate the change in pressure (

) between the nozzle entrance and its exit.

- Calculate the velocity (

) of the water in the deflected jet.

- Determine the magnitude and direction of the force on the bracket.

1. This is what the control surface with annotations should look like. Notice that there are two control volumes, with the output flow from one control volume feeding into the other.

2. The velocity of the water entering and exiting the nozzle can be determined using the conservation of mass (continuity equation), i.e.,

The entrance area () is

Therefore, the entrance velocity is

For the exit velocity, , the continuity equation gives

3. Using Bernoulli’s equation, then

Rewriting for the pressure change gives

Substituting values then gives

4. The velocity of the deflected jet can be determined using continuity, i.e.,

Rearranging gives

5. The force on the bracket is determined from the rate of change of momentum. Assuming the system is open to the atmosphere and pressure forces are insignificant, then

Substituting the values gives

For the -direction, then

The reaction force on the bracket is then

which is to the right and downward.

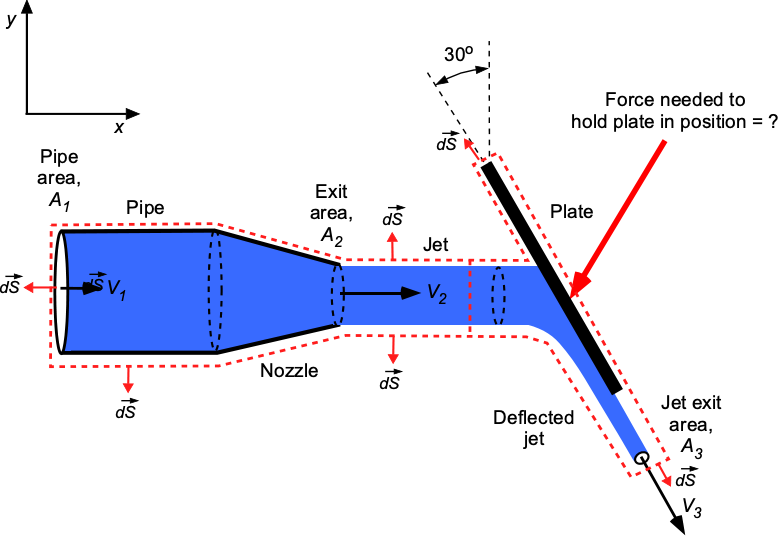

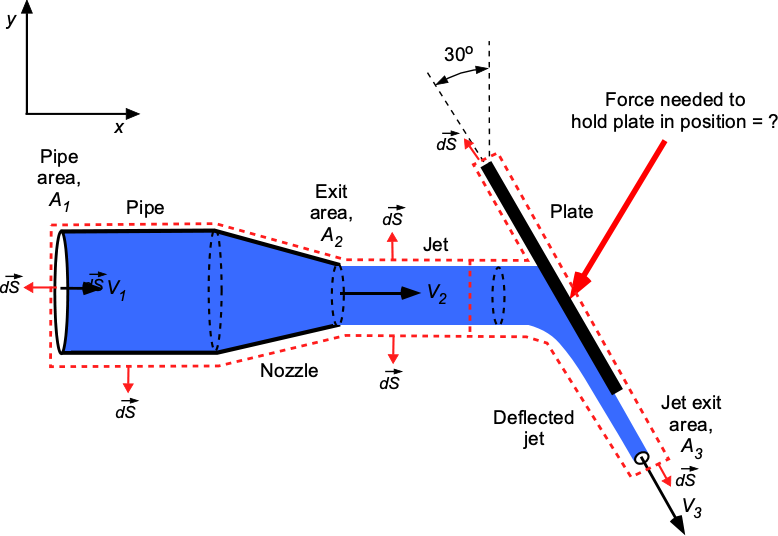

Worked Example #32

Water flows from a circular pipe through a nozzle and is diverted as a circular jet onto an inclined plate with a circular groove that maintains the jet’s circular form, as illustrated in the figure below. The diameters are cm,

cm and

cm. If the flow rate is

= 0.00687 m

s

, what force is required to hold the plate in position? Assume uniform flow properties across any cross-section of the flow. Assume a steady flow with no losses. Neglect all pressure and gravitational effects. Hint: Be sure to show the control surface around the problem and the directions of the unit normals. The density of water is 1,000 kg m

.

The relevant forms of the continuity and momentum equations based on the assumptions are

and

In one-dimensional form (uniform flow properties across any cross-section), the continuity equation can be written as

For flow in the plane, the corresponding momentum equation in terms of its scalar components is

where is the change in the flow velocity in the

direction, and

where is the change in the flow velocity in the

direction, and where in each case

is the mass flow rate.

The control volume is shown in the figure below. From 1 to 2 over the nozzle, then

Because the flow is incompressible, then

so

We are given the flow rate,

We are given the flow rate, , so

where

Inserting the values gives

The velocity at section 2 is

The mass flow rate is

From sections 2 to 3, the flow is deflected by a plate. Applying conservation of mass, then

The force on the fluid is equal to its time rate of change of momentum, i.e.,

Substituting the values gives

and

Therefore, the force on the fluid is

And the force on the plate is

which is upward and to the right.