11 Fundamental Properties of Fluids

Introduction

Aerodynamics is the underpinning of atmospheric flight, so understanding aerodynamic principles, or, more generally, fluid dynamic principles, is critical to successfully designing all types of flight vehicles. Aeronautical and astronautical engineers must understand the behavior of fluids under a broad range of conditions. Fluids can be liquids or gases, and air is a gas. To understand the action of aerodynamic flows on flight vehicles, it is first necessary to become intimately familiar with the fundamental physical properties used to describe the behavior of fluids and the relationships between them. This general field is called fluid mechanics[1]. One must learn about fluid mechanics and aerodynamics before a deeper understanding of the other characteristics of flight vehicles becomes possible.

In all branches of science and engineering, physical properties are defined to help describe how things behave in the physical world. For example, mass, weight, energy, work, power, etc., are all essential properties relevant to physical behavior and problem-solving. The pertinent properties of fluids include pressure, density, temperature, viscosity, flow velocity, and the speed of sound. These are also point properties in that their values can change from one spatial location to another in the fluid; they may also vary with respect to time at a given spatial location. These are called macroscopic properties. [2] In this regard, they apply to bulk matter or a finite group of molecules rather than to each molecule, the matter having net physical dimensions much greater than the mean free path[3] between the molecules; this approach is known as a continuum assumption.

Furthermore, it must be recognized that these fluid properties will not be independent of one another, i.e., they will have some interdependencies, often through the effects of temperature. Changing the value of one property inevitably means that the values of other properties may also vary. For example, increasing the pressure of air, such as by compressing it, is accompanied by an increase in density and temperature. The relationships between pressure, temperature, and density can be established using thermodynamic principles and the ideal gas laws, which are formally encapsulated in an equation of state.

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the continuum model for describing a fluid.

- Become familiar with the parameters used to describe a fluid’s behavior, including pressure, density, temperature, viscosity, flow velocity, and the speed of sound.

- Use the equation of state to relate the properties of a gas, such as pressure, density, and temperature.

- Understand the concept of viscosity and how to calculate the viscosity of a gas using Sutherland’s law.

- Know about the differences between diffusion and effusion of a gas.

- Understand what streamlines are in a flow and how to calculate their locations.

- Know how to calculate the speed of sound in a fluid.

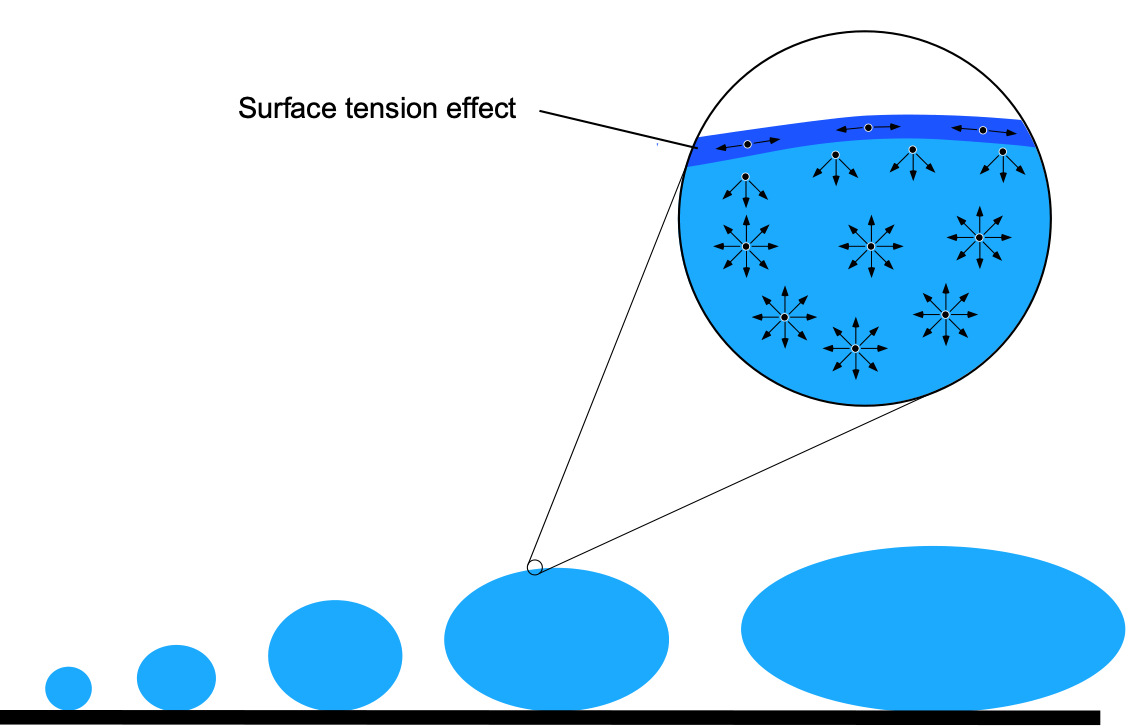

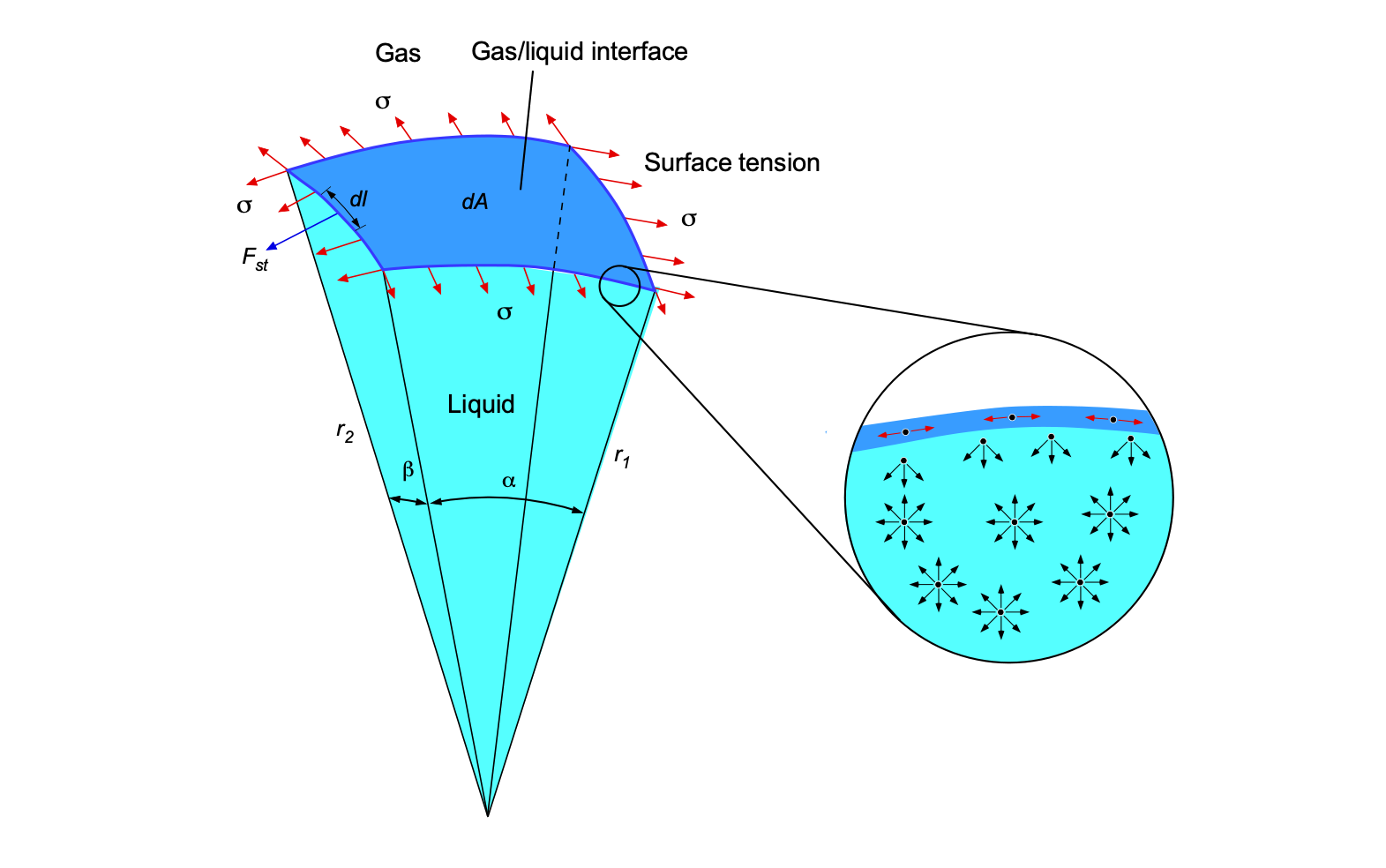

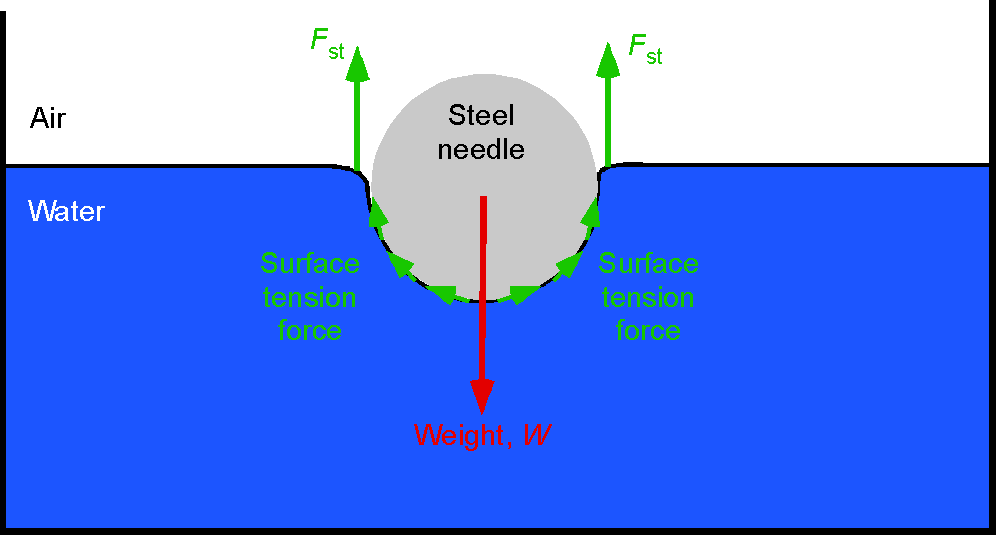

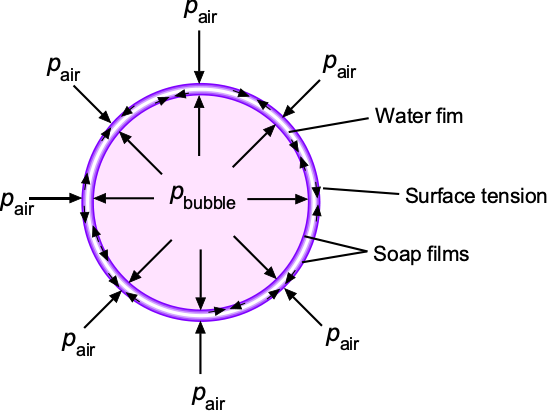

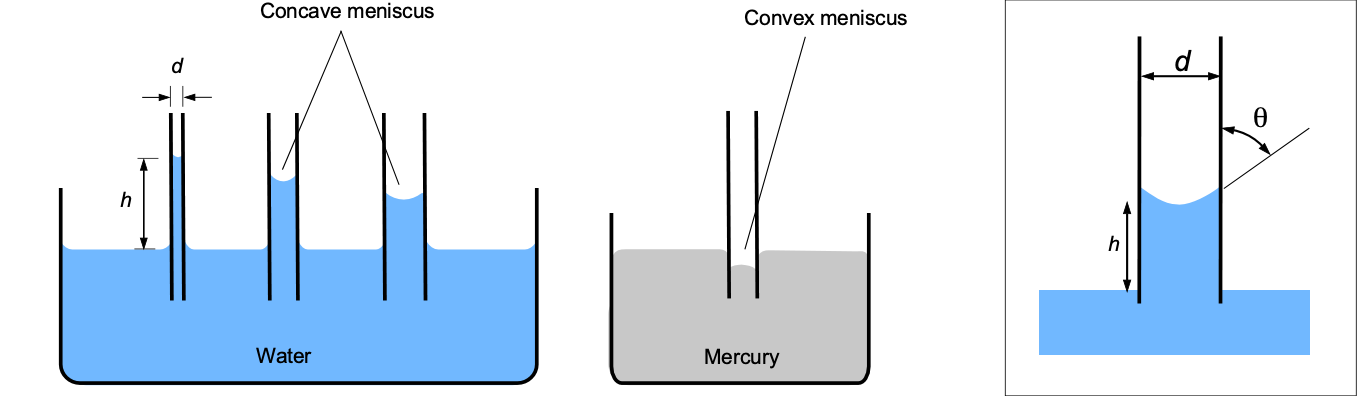

- Appreciate the concepts of surface tension and capillary action and how they can affect the behavior of fluids.

What is a Fluid?

Fluids are substances with mass and volume but have no predefined shape and can easily flow. They can be liquids (e.g., water) or gases (e.g., air). Unlike solids, fluids have relatively mobile molecules, as illustrated in the figure below. In a solid, the molecules are tightly packed in a lattice and have no mobility, except for tiny vibrations around their fixed positions. Solids are primarily rigid and have shapes that are difficult to change under the action of external forces.

However, the molecules are further apart and much more mobile in fluids. This characteristic means that fluids are easily deformed and will flow readily under the action of external forces. It is the tendency for fluids to flow and continuously deform under the action of an applied force that makes them more difficult to understand. Of particular interest to aerospace engineers is the gas commonly referred to as “air.” Like all gases, air is composed of molecules that are relatively far apart from one another. Air can be compressed relatively easily, which has numerous consequences for the aerodynamic characteristics of flight vehicles.

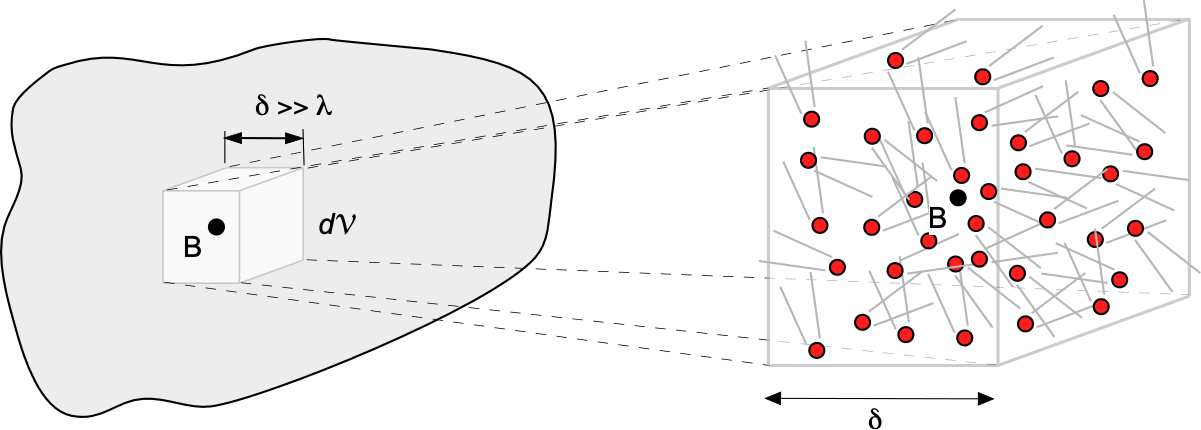

Concept of a Continuum

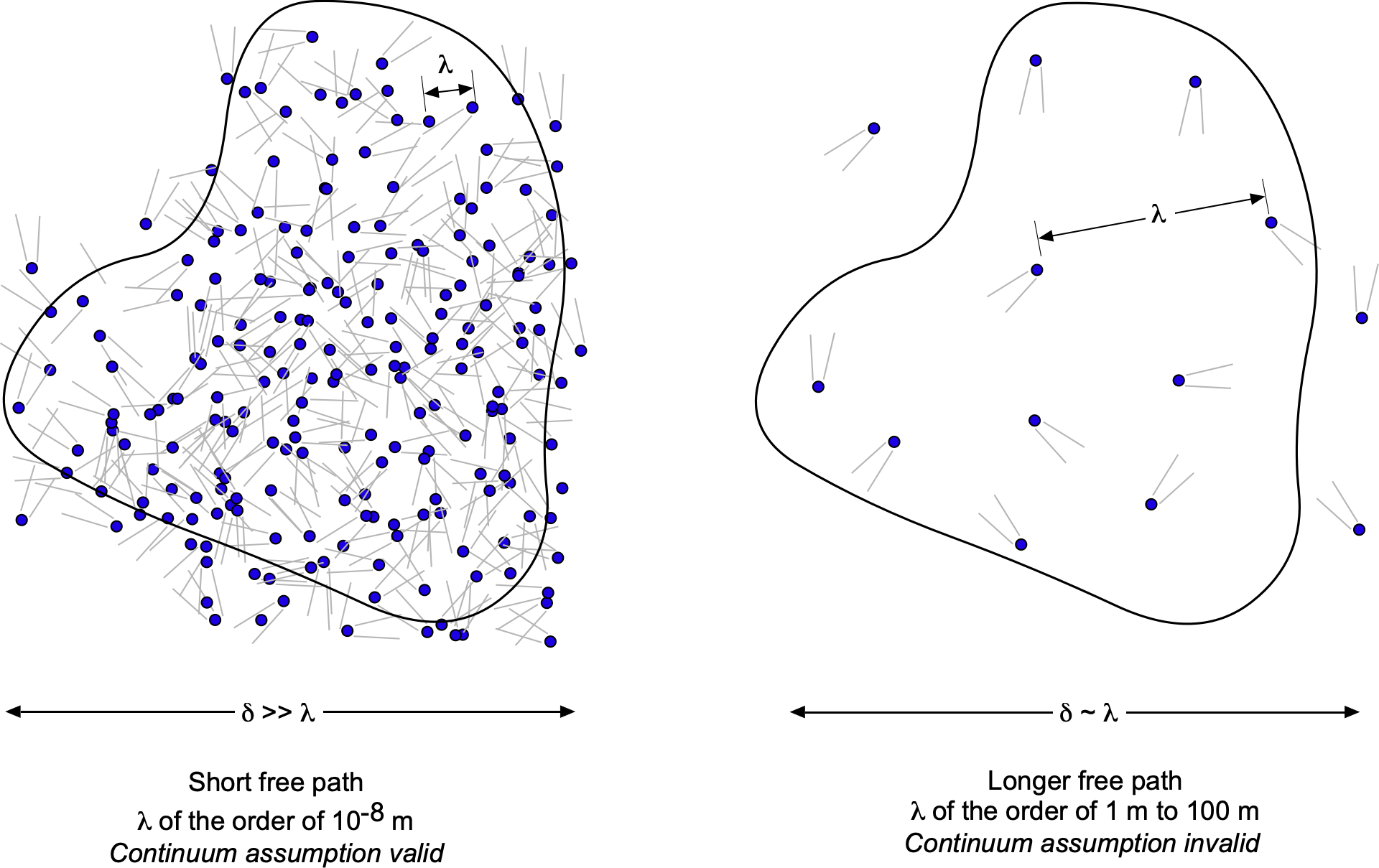

A molecular model of the flow is employed to describe the behavior of a fluid based on the concept of a continuum. In a continuum model, it is assumed that the distance between individual fluid molecules, or more specifically, their mean free path, denoted by the length scale , is tiny compared to the scale and physical dimensions of the problem,

, as suggested in the figure below. With a continuum model, the macroscopic fluid properties, such as temperature, density, pressure, and flow velocity, can be considered constant at any point in space and vary continuously from point to point within the physical dimensions of the problem. In a continuum, any local changes associated with individual molecular motion are irrelevant, which is easily justified in most practical cases of fluid flows.

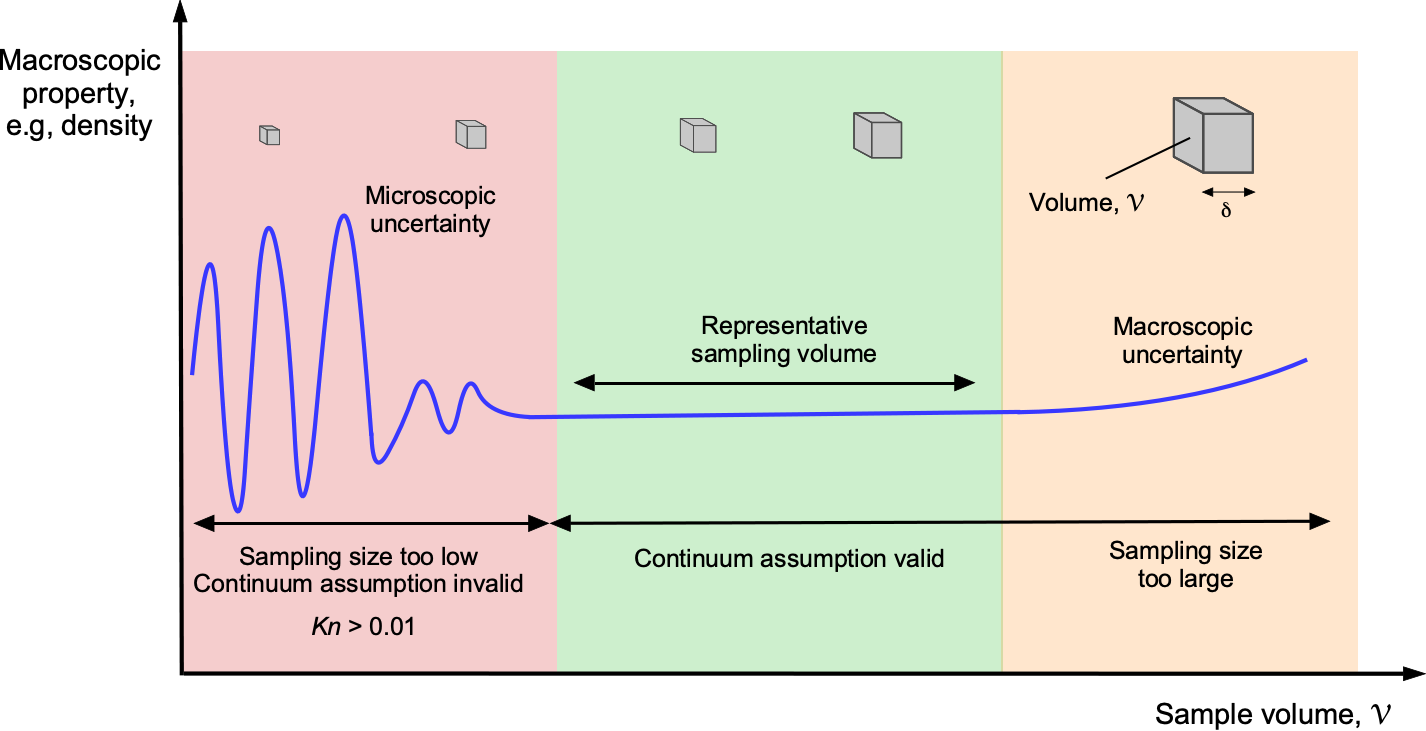

One way to think about a continuum is to consider a measurement volume, , like a probe used in a wind tunnel to measure pressure. The figure below shows the measurement volume at different scales,

. When

is very small, it contains only a few molecules, making it difficult to accurately define macroscopic properties such as density, temperature, and pressure. As

increases, it encompasses more molecules, allowing the averaged properties to converge to well-defined macroscopic values. This is the essence of the continuum assumption: that at sufficiently large scales, the discrete nature of matter can be ignored, and the material can be treated as a continuous medium. Eventually, as

becomes too large, the macroscopic properties can vary within the volume, making it challenging to make a valid measurement of “point” macroscopic properties.

A continuum model is the most common approach used to describe a fluid, and this assumption will be employed throughout this e-book to describe fluid properties. But why does this distinction of a continuum matter for flight vehicles? For a gas such as air in the lower atmosphere, the mean free path is on the order of

m. The physical dimensions of a flight vehicle flying in the lower atmosphere will be many orders of magnitude greater than

. Therefore, in this case, the fluid flow around the vehicle can be considered a continuum, and all standard macroscopic properties used to describe a fluid, such as pressure, density, and temperature, would apply.

However, consider a situation where becomes comparable to the length scale of the flight vehicle, such as at the edge of space, where the air density is very low and satellites operate in low Earth orbit. At an altitude of 100 km,

ranges from 0.1 to 1 m, while at 300 km,

exceeds 100 m. In this context, air molecules are spaced far enough apart that interactions with the vehicle occur infrequently. As a result, the properties will not vary continuously from point to point, meaning the flow cannot be considered a continuum and will behave differently.

The Knudsen number, , is often used to quantify such low-density flows. The validity of the continuum assumption is inherently tied to the collision rate of the molecules in the gas. Therefore, letting

represent the intermolecular collision rate or frequency, i.e., collisions per unit time, and

represent the characteristic flow time, the Knudsen number (which is a non-dimensional similarity parameter) can be defined as

(1)

Alternatively, if is the mean molecular speed,

is the mean free path (the average distance traveled by a molecule before encountering a collision), and

represents a characteristic length scale, then

(2)

Therefore, the ratio of to a characteristic length,

, becomes a measure of the degree of departure from a continuum.

Usually, when the value of is larger than 0.01, it has been found that the continuum concept becomes increasingly invalid. When

is greater than 0.01 and approaching 1, the conditions can be described as a free molecular flow. Under such conditions, the mean free path of the molecules becomes of the order of or greater than the characteristic length scale, and intermolecular interactions are infrequent. As a result, the gas behavior cannot be explained in terms of macroscopically varying quantities; it must be described using a rarefied gas model, where the behavior of individual molecules must be described, usually through statistical models.

However, the definition of a characteristic length scale may need to be qualified. Choosing a length scale, such as the flight vehicle’s length, provides a global measure of how well the continuum assumption applies at a given flight condition. Another choice is to use a length scale related to the local flow characteristics, in which case the continuum concept may become invalid at different flight conditions, depending on the location in the flow.

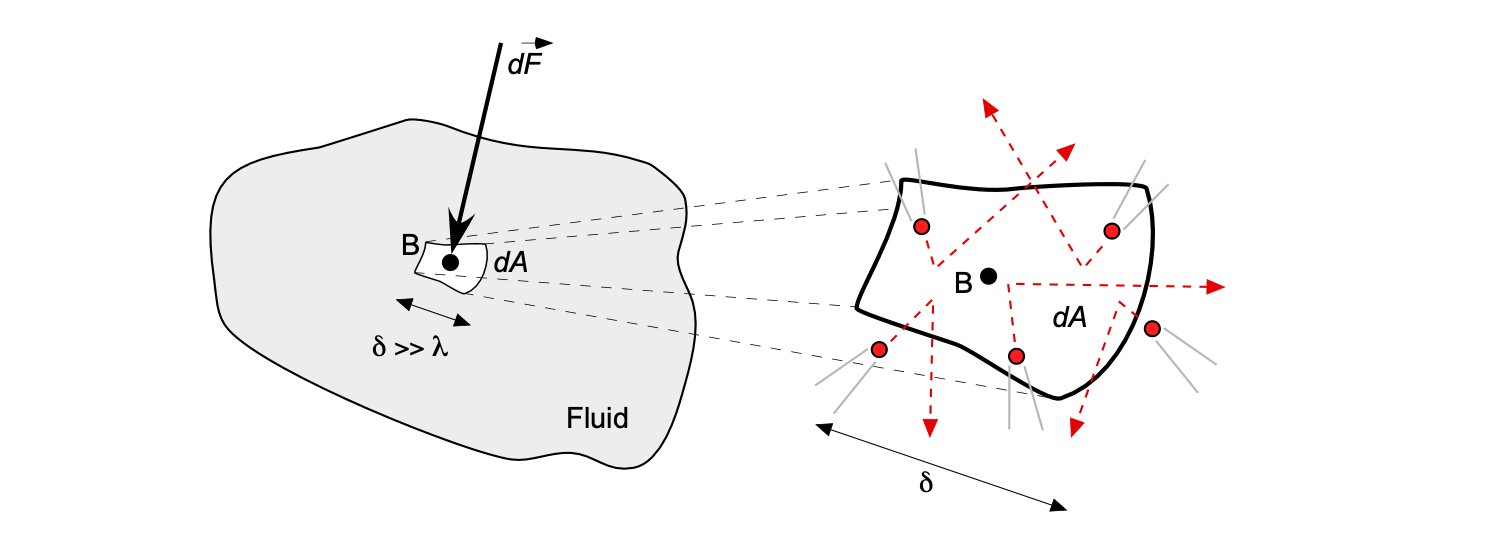

Fluid Pressure

Remember that fluid is full of many relatively mobile molecules. In physical terms,[4] the pressure can be thought of as the magnitude of the force

produced in a direction normal to this elemental area from the average reaction force (i.e., the time rate of change of momentum) of the molecules per unit time are impacting upon this surface.

Therefore, the pressure at point B in a fluid can be defined as

(3)

where is a measurable dimension compared to the mean distance between the fluid molecules, i.e.,

.

This latter definition means that the pressure is the limiting form of the time-averaged force per unit area as the area shrinks to a point, but that “point” is still big enough to be described by a continuum model. With the assumption of a continuum model, the area cannot shrink to zero because the pressure in the fluid will result from the random movement of individual molecules.

Notice that pressure can be interpreted as a normal compressive force per unit area, which can be recognized as equivalent to a stress. The physical interpretation of pressure assumes that it is caused by the time rate of change of momentum of the fluid molecules, such as when they might strike the walls of a surface or a container. Higher or lower pressure would be associated with more or fewer molecules impacting a given surface area per unit of time. So, a large force must be exerted to create a large amount of pressure on a given area. Alternatively, this same force must be exerted over a small area to get a higher pressure.

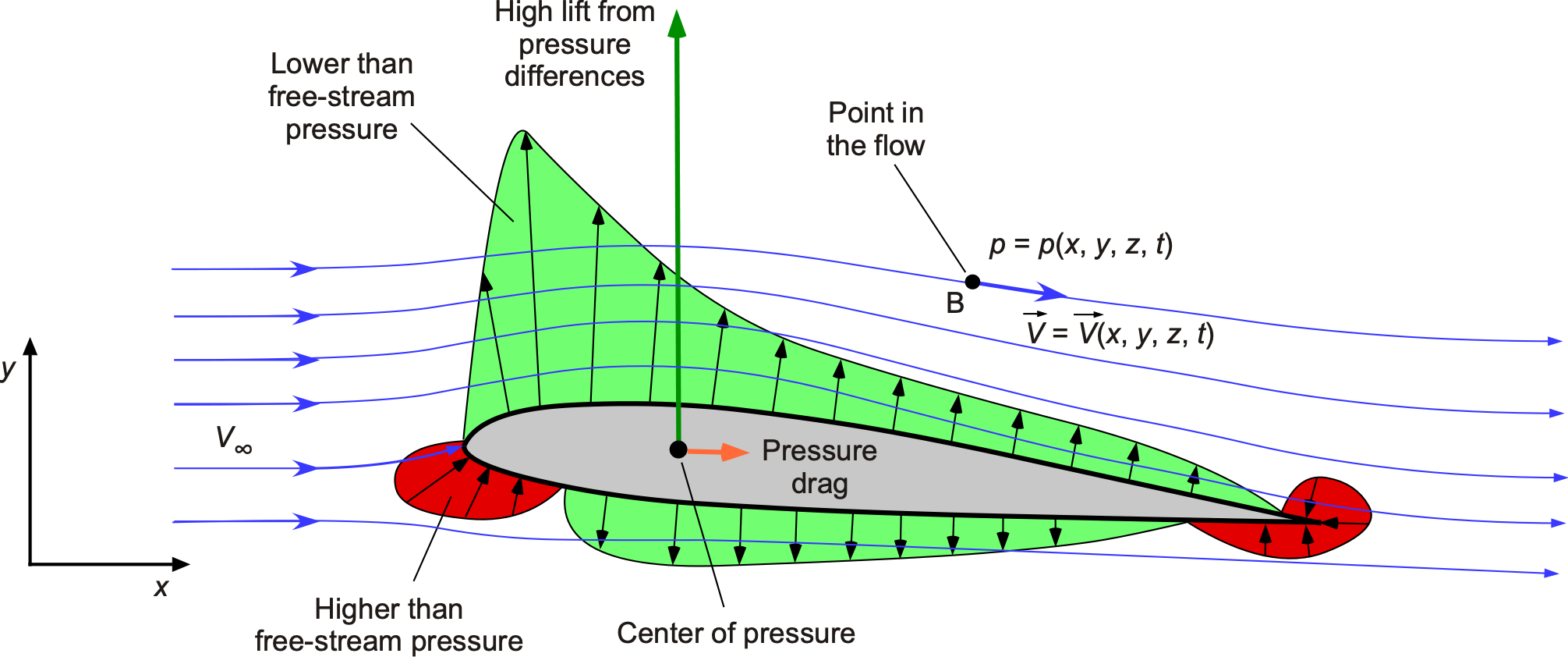

Pressure is also a point property, meaning that its value can differ from one point to another throughout the fluid, e.g., when the flow moves around a shape such as an airfoil section, as shown in the figure below. Well upstream of the airfoil “at infinity,” the flow velocity and pressure are constant, i.e., the velocity is , and the static pressure is

. However, both the local velocity and pressure will change near the airfoil. Pressure is also related to other fluid properties, such as flow velocity

, density,

, and temperature,

. Therefore, the pressure becomes a function of the Cartesian spatial coordinates, i.e.,

. Sometimes, the pressure value at a point may also change over time (the symbol

denotes time); therefore, pressure can be written more generally as

. It is also essential to recognize that pressure is a scalar quantity (it has magnitude but no direction), and at a given point, the pressure has the same value in all directions, a principle known as Pascal’s Law.

How is the value of quantified?

The term “measurable dimension” regarding pressure or other point properties can be considered equivalent to the diameter of the tip of one’s pen or pencil, so about 0.5 mm or 0.02 (twenty-thousandths) of an inch. In the wind tunnel, pressure probes, pressure tubing, and the pressure-measuring area of transducers are typically of this dimension. Anything larger means that point properties are not being recorded. Anything smaller means the pressure is acting over an area that is too small for a sufficiently sizable integrated effect to be recorded as a valid measurement.

Units of Pressure

Pressure has engineering units of N m or Pascals (Pa) in the SI system or lb ft

(pounds per square foot) in the U.S. Customary (USC) system. In practice, kilo-Pascal (kPa) units may be used because a Pascal is a small pressure value. Units of hectopascals are often used in barometric pressure measurements, where one hectoPascal (hPa) is equal to 100 Pascals. One hPa equals one millibar; one bar is 100,000 Pa or 100 kPa. However, a bar is not an SI unit, and its use should be avoided in most engineering applications unless specifically called for. In the USC system, units of lb in

(pounds per square inch) are also common; converting from units of lb in

to units of lb ft

requires a multiplication factor of 144, i.e. one lb in

= 144 lb ft

Pressure as a Force

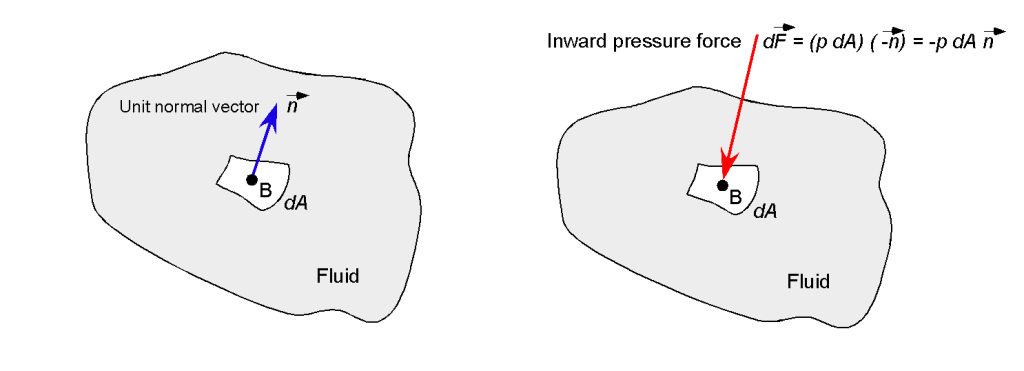

Sometimes, the effects of pressure may be interpreted as a force, i.e., as a quantity with magnitude and direction. However, pressure can be viewed as a force only when the area and orientation of a surface over which the pressure acts are specified. Therefore, a line of action is also needed to resolve the effects of the pressure and find the force on a surface over which the given pressure acts.

For example, if the small elemental surface had an outward-pointing unit normal vector , as shown in the figure below, then the pressure force normal to the surface would be

(4)

where the minus sign indicates that the pressure force will act inward in the opposite direction to the outward pointing direction of .

What is a physical interpretation of a pressure force?

Consider what happens when you scuba dive in the ocean or dive deeply into a swimming pool. The pressure exerted by the water above feels like a squeezing force on one’s body. Water is three orders of magnitude denser than air, meaning it has many times more molecules per unit volume. Therefore, only relatively small changes in depth are required for one’s body to feel significant changes in pressure. One will feel this pressure first on the ears, which are very sensitive to pressure changes; they respond over several orders of magnitude. The Eustachian tubes, also known as the auditory tubes or pharyngotympanic tubes, are a narrow passage that connects the middle ear to the back of the nose, helping to regulate external pressure. When the pressure outside the ear changes, one may feel discomfort or even pain as one’s ears adjust to the increased pressure, which can be achieved by yawning or swallowing. The opposite occurs when one returns to the surface, which also requires adjusting the differential pressure in the Eustachian tubes to match atmospheric pressure.

Check Your Understanding #1 – Calculation of a pressure force

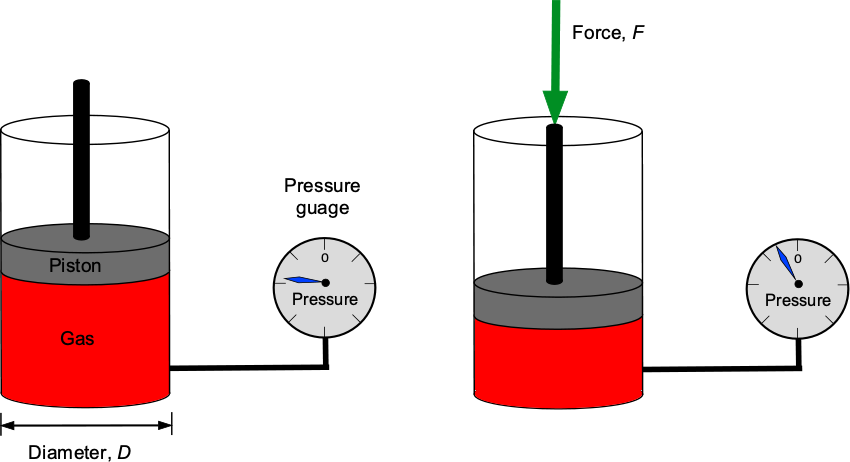

A piston pushes down on a trapped volume of gas in a cylinder with a diameter of 3 inches. A pressure gauge measures the pressure in the gas to be 11 lb/in2. What is the force applied to the piston? Repeat the problem in SI units if the piston diameter is 76 mm and the pressure is 75.8 kPa.

Show solution/hide solution.

By definition, pressure, , is the force,

, divided by area,

, so

which can be assumed to act uniformly. The area of the piston is

Therefore, the force in USC units will be the pressure times the area, i.e.,

In SI units, then = 76 mm and

= 75.8 kPa, so the force will be

Fluid Density

Another essential property to describe a fluid’s characteristics is its density, given the symbol or

. Because the symbol

used for pressure looks similar to

, it is better to use

for density to preserve clarity, especially when

and

are used in the same equation.

Again, consider some point B in the fluid, as shown in the figure below. Let be an elemental volume surrounding point B, and

is the associated mass of fluid inside

. In the continuum assumption, millions of molecules will remain within the small elemental volume. Density is defined as the mass of a fluid per unit volume, which measures the number of molecules per unit volume. Mass is usually given the symbol

. Volume is given the symbol

, i.e., a curly form of “V.” Notice: Do not confuse volume

with velocity

, the latter usually being written in vector form, i.e.,

.

The density of the fluid at point B is formally defined as

(5)

where is a large linear dimension compared with the mean distance between the molecules

. Therefore, flow density refers to the ratio of the mass of a small volume of fluid to the volume that contains it. Flow density is also a scalar quantity, and, in general, like pressure, it can be written as

.

Units of Fluid Density

Fluid density has units of kg/m (or more appropriately as kg m

) in the SI system or slugs ft

in the U.S. customary or USC system, where the slug is the base unit of mass.[5][/footnote] In dealing with aerodynamic problems, it is helpful to remember that air has a density of 1.225 kg m

or 0.002378 slugs ft

at sea level standard temperature and pressure. These values are at mean sea level (MSL) as defined in the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) and are usually designated as the symbol

.

Other types of measurement values of fluid density may be used in practice, mainly when dealing with liquids, which may be referenced to the density of water. These values include specific volume, specific weight, and specific gravity.

Specific Volume

The specific volume of a fluid is the reciprocal of its density and is given the symbol or

and can be expressed as

(6)

The units of specific volume are volume per unit mass, so m/kg (i.e., m

kg

) in the SI system, or the USC system it will have units of ft

/slug (i.e., ft

slug

).

Specific Weight

The specific weight is the weight of a unit volume of a fluid. It is often denoted by the symbol or

, i.e.,

(7)

Specific weight has units of weight per unit volume, so its value depends on acceleration under gravity or “g.” The units of specific weight are N/m (i.e., N m

) in the SI system or lb/ft

(i.e., lb ft

) the USC system.

Specific Gravity

When dealing with liquids, their density is often measured relative to another fluid, called the specific gravity, . Usually, the reference is the density of water, so

(8)

Notice that specific gravity is a non-dimensional or unitless quantity. is the most common alternative measurement of fluid density.

Fluid Temperature

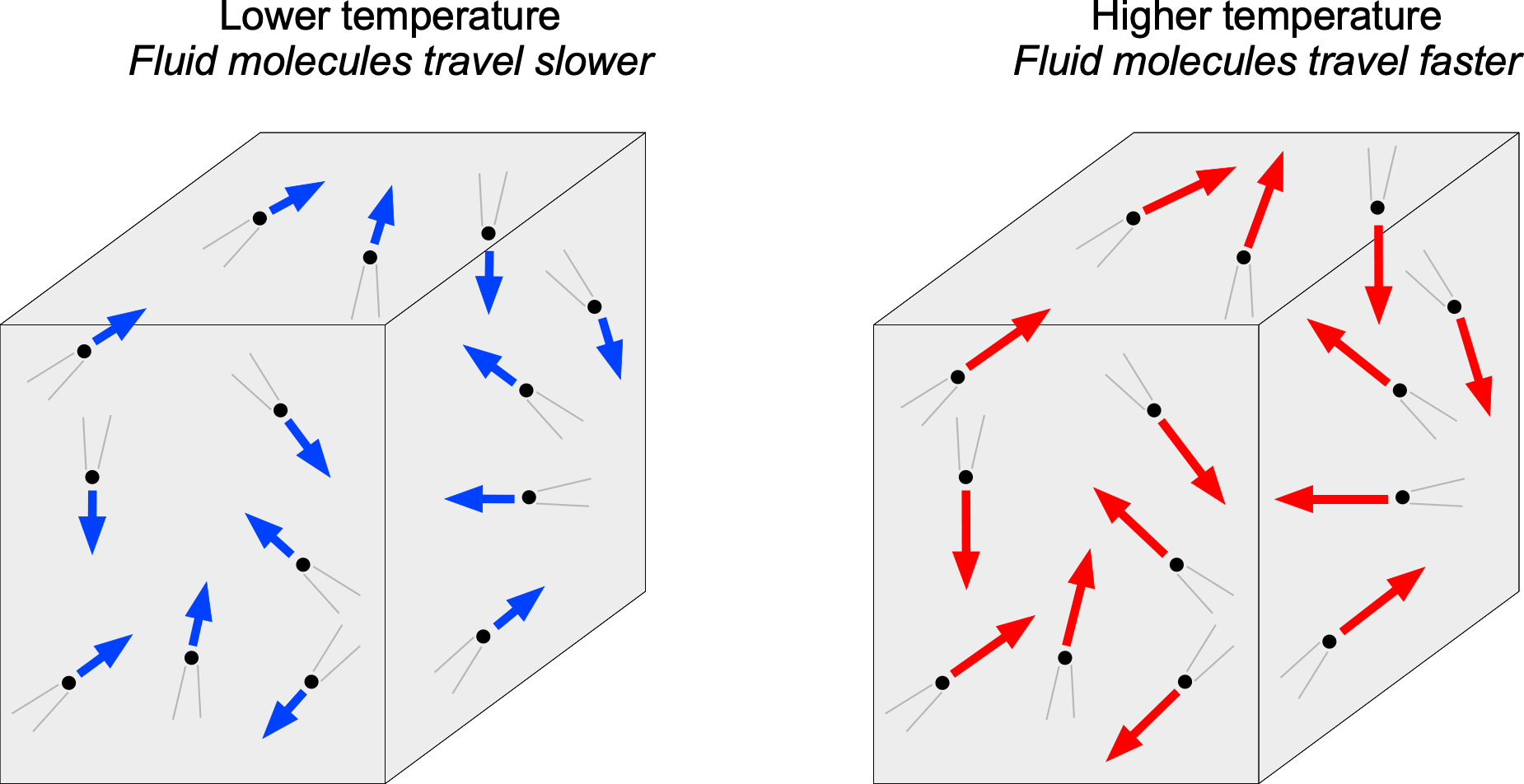

The temperature in a fluid is given the symbol and is related to the average internal energy of the molecules at that point in the fluid. Temperature affects fluid properties differently, depending on whether the fluid is a liquid or a gas, as well as its molecular composition. Temperature plays a vital role in aerodynamics, where the air is compressible, and aerodynamic heating from frictional effects can occur.

Again, the molecular model can help explain the concept of temperature. This relationship is typically written as , where

is known as Boltzmann’s constant, which serves as the conversion factor that connects energy to temperature. The Boltzmann constant is defined as 1.380649×10−23 J K−1 in SI units, the Joule (J) being the unit of energy. Therefore, as shown in the figure below, a higher-temperature fluid would be one in which the molecules move about at relatively high speeds. In contrast, a lower-temperature fluid would be one with relatively low molecular speeds. Temperature is also a point scalar property. In general, the temperature in a fluid will vary from point to point; temperature may also vary with time at a given point, i.e.,

.

The relationship that the total energy strictly holds for monoatomic gases, which have three degrees of translational freedom, i.e., kinetic energy only. Diatomic gases, such as nitrogen and oxygen, which comprise approximately 98% of air, also exhibit two degrees of rotational motion and two degrees of vibrational motion, the latter being important only at higher temperatures. Therefore, their total internal energy will be related using

at lower temperatures and

at higher temperatures.

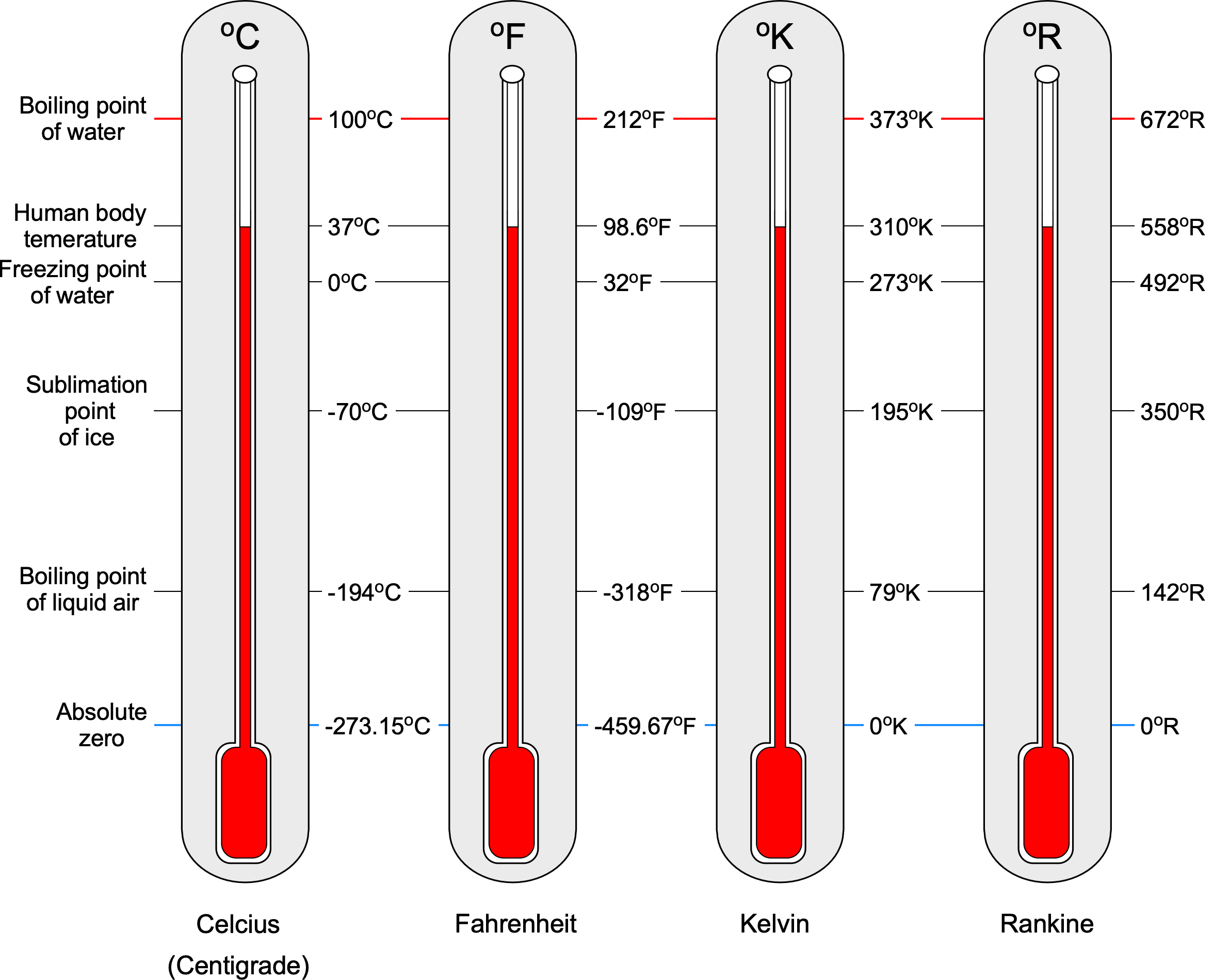

Units of Temperature

Two fixed points are taken to construct a temperature scale. The first fixed point is the freezing point of water, called the lower fixed point or . The second fixed point is the boiling point of water, which is called the upper fixed point or

. Temperature is measured in units of Centigrade or Celsius

C or Kelvin, K or

K, in the SI system or Fahrenheit

F or Rankine, R or

R, in the USC system.

Celsius or Centigrade Scale

This scale was devised by Anders Celsius in 1710. The interval between and

is 100 units, where each unit is called one degree Celsius (

). In this scale, then the lower fixed point is

= 0

C (freezing point of water), and the upper fixed point is

= 100

C (boiling point of water).

Fahrenheit Scale

This scale was devised by Gabriel Fahrenheit in 1717. The interval between and

is 180 units, where each unit is called one degree Fahrenheit (

). In this scale, then the lower fixed point is

= 32

F and the upper fixed point is

= 212

F.

Kelvin Scale

This scale was devised by William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) in 1848. The zero temperature is absolute zero[6] on this scale. It is the thermodynamic scale for use in SI units. The interval between and

is 100 units, where each unit is called one degree Kelvin (

or

). In this scale, then the lower fixed point is

= 273.15

K, and the upper fixed point is

= 373.15

K.[7]

Rankine Scale

This scale was devised by William John Macquorn Rankine in 1859. On this scale, the zero temperature is also equivalent to absolute zero. It is the thermodynamic scale for use in USC units. The interval between and

is 80 units, where each unit is called one degree Rankine (

R or 1 R). In this scale, then

= 492.67

R, and

= 672.67

R.

Temperature Scale Conversions

Converting from one temperature scale to another is straightforward because they are all linearly related, as shown in the figure below; this figure should not be used for numerical calculations. Converting to Centigrade or Celsius C from Fahrenheit

F is performed using

(9)

Converting to Fahrenheit from Centigrade or Celsius

uses

(10)

Converting to Kelvin K from Centigrade or Celsius uses

(11)

Finally, converting to Rankine R from Fahrenheit uses

(12)

Notice that it is often suggested that the degree symbol () not be used when citing temperature units (especially for the Kelvin and Rankine scales). However, many publications can be found with and without the degree symbol. Nevertheless, retaining the degree symbol on the temperature units is entirely acceptable for students and others when working on aerodynamic problems. Finally, it is helpful to remember the standard sea level values of temperature (based on the ISA model), usually given the symbol

, which are 15

C = 59

F = 288.15

K = 518.67

R.

Using Temperatures in Engineering Problem-Solving

In engineering problem-solving, caution should be applied so that the correct absolute (engineering) units of temperature are used, i.e., units of Kelvin or Rankine, because these scales measure the temperature relative to absolute zero temperature, i.e., the temperature when the average internal energy and motion of the molecules becomes effectively zero. For example, for two temperatures and

= 40

, then the ratio

is written correctly as

(13)

but incorrectly as

(14)

Why two absolute temperature scales?

Using two absolute temperature scales is a historical outcome of different conventions and preferences in various fields, including physics and engineering. The Kelvin (K) absolute temperature scale, proposed in 1848 and based on the Celsius (C) unit, is named after Sir William Thomson, a professor of natural philosophy (physics) at the University of Glasgow, who later became Lord Kelvin. Interestingly enough, Kelvin was skeptical of the future of aviation, refusing to join the Royal Aeronautical Society, stating that “I have not the smallest molecule of faith in aerial navigation other than ballooning or of expectation of good results from any of the trials we hear of.” The Rankine (R) scale, also an absolute thermodynamic temperature scale, was proposed in 1859 based on the Fahrenheit (F) unit. This scale is named after William J. M. Rankine, the first University of Glasgow engineering professor.

Combined Gas Equation & Equation of State

Having introduced the concepts of pressure, density, and temperature, it is also essential to recognize that these quantities have interdependencies, i.e., changing one value affects the others. In physics and chemistry, there are four fundamental gas laws: Boyle’s Law, Charles’s Law, Gay-Lussac’s Law, and Avogadro’s Law. These are all empirical gas laws because their relationships were derived from laboratory experiments with gases.

Gas Laws

Boyle’s law states that for a constant mass, the volume of the gas is inversely proportional to its pressure, i.e.,

(15)

where conditions 1 and 2 refer to the initial and final conditions, respectively.

Charles’s law states that for a gas at a constant pressure, its volume is proportional to temperature, i.e.,

(16)

Gay-Lussac’s law states that at a constant mass and volume, pressure is proportional to temperature, i.e.,

(17)

Combined Gas Law

These three laws can be combined, leading to the combined gas law, which is written as

(18)

This is a thermodynamic equation. All gases have properties that can be measured, including their pressure, temperature, and volume. Numerous scientific experiments and careful measurements have determined that these variables are quantifiably related. For a given mass of gas, if any two properties can be determined (i.e., measured or calculated), the combined gas law can be used to determine (calculate) the other.

Equation of State

Avogadro’s law states that the amount of a gas, usually in terms of moles, is proportional to its volume at constant pressure and temperature, i.e.,

(19)

where is the mass of the gas expressed in moles. Remember that 1 mole = 6.022

10

atoms, which is called Avogadro’s number,[8]

, so a mole (a base unit) expresses the density of the gas.

These preceding relationships are now formally embodied in an equation of state, which determines the quantitative relationships between a gas’s pressure, density (or mass and volume), and temperature. In physics and chemistry, people inevitably first come across the use of the general or universal equation of state for a gas, i.e.,

(20)

where is called the universal gas constant, which is the same for all gases. The universal gas constant,

, is related to the Boltzmann constant,

, by

.

However, this latter equation of state is not particularly useful for engineering purposes, especially for finding and relating fluid properties at a point. But, if both sides of this general equation are divided by the mass of the gas, then the volume now becomes the specific volume, , which is the reciprocal of the density of the gas. Recall that the “specific” in the term specific volume means “divided by mass,” i.e.,

(21)

Therefore, an alternative but equivalent equation of state for a gas can be written as

(22)

which is more usually written as

(23)

Equation 23 is the usual form of the equation of state used in engineering, gas dynamics, and aerodynamics. Notice also that this result is independent of the volume of the considered gas. However, in this case, another (different) gas constant, , is used, which equals the universal gas constant divided by the gas’s mass per mole, i.e.,

(24)

Therefore, the value of in Eq. 23 is not universal and depends on the gas type; in this case, the value of the gas constant is specific to the gas. Subsequently, caution should be exercised to ensure that the correct value of

is used in engineering calculations for each gas being considered, along with the proper units.

However, it is useful to remember that all the forms of the equation of state are equivalent, i.e.,

(25)

and which version to use depends, in part, on the problem being solved. Because point properties are often desired in engineering problems with fluids, the most common form of the equation of state is

(26)

What are the units of the gas constant?

In SI units, the gas-specific constant , is measured in J kg

K

. In USC, the units of

are ft-lb slug

R

. A consistent set of units must be used throughout engineering calculations, with base units of mass, length, and time being preferable. Remember that a Joule (J) is equivalent to a Newton-meter (N m), so it has base units of kg m

s

.

The main advantage of the equation of state in the engineering form is that if the values of two quantities are known, e.g., pressure and temperature, which are both easily measured, it allows the calculation of the other quantity, i.e., the density, which is obtained from the equation

(27)

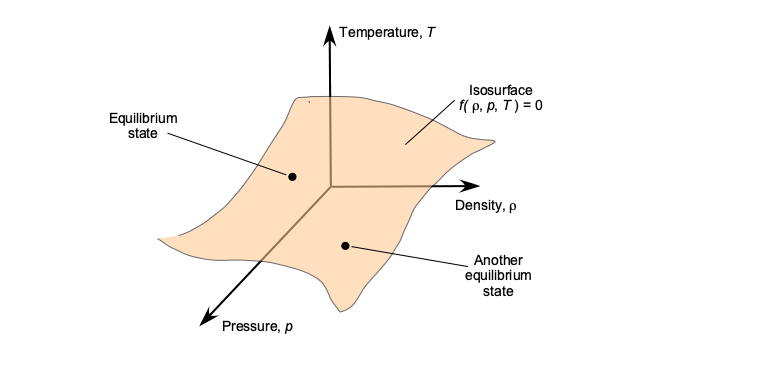

Therefore, using the equation of state reduces the number of independent quantities from three to two. The equation of state can be interpreted as a two-dimensional surface in the ,

and

state space, i.e., a surface defined by a function

, as shown in the figure below, so that every point on the surface represents a unique equilibrium thermodynamic state of the gas.

Strictly speaking, the preceding equation of state in Eq. 23 applies only to an ideal gas, i.e., one where the molecules are sufficiently far apart that intermolecular bonding forces are relatively low and that intermolecular collisions are perfectly elastic. Under what might be called “normal conditions,” at temperatures and pressures reasonably close to standard atmospheric conditions, air behaves like an ideal gas. Generally, a gas nearly always acts as a perfect gas at normal to moderate temperatures and/or pressures. It behaves less ideally at very low temperatures and/or high pressures.

Check Your Understanding #2 – Calculation of air density

During measurements in a wind tunnel, the pressure and temperature of the air are found to be 102.3 kPa and 15.7C, respectively, in SI units. Calculate the air density in the tunnel. Repeat the problem if the pressure is measured in USC units as 14.61 lb in

(pounds per square inch or psi) at a temperature of 71.1

F.

Show solution/hide solution.

Because this question involves pressure, temperature, and density, we will use the equation of state, i.e.,

where is pressure,

is density,

is absolute temperature, and

is the gas constant, in this case, for air. Rearranging for the density gives

The first part of the problem is in SI units. In this case, the absolute temperature is 15.7 + 273.15 = 288.85 K. The gas constant for air in SI units is 287.057 J kg

K

so the density of the air will be

Remember that for engineering calculations, we must always use absolute temperature.

The second part of the problem is in USC units. In this case, the absolute temperature is 71.1F + 459.67 = 530.77 R. The pressure is given in terms of common units of pounds per square inch (psi), so to convert to base USC units of pounds per square foot (psf or lb/ft

), it is necessary to multiply by 144. The gas constant for air in USC units is 1716.49 ft-lb slug

R

, so the density of the air will be

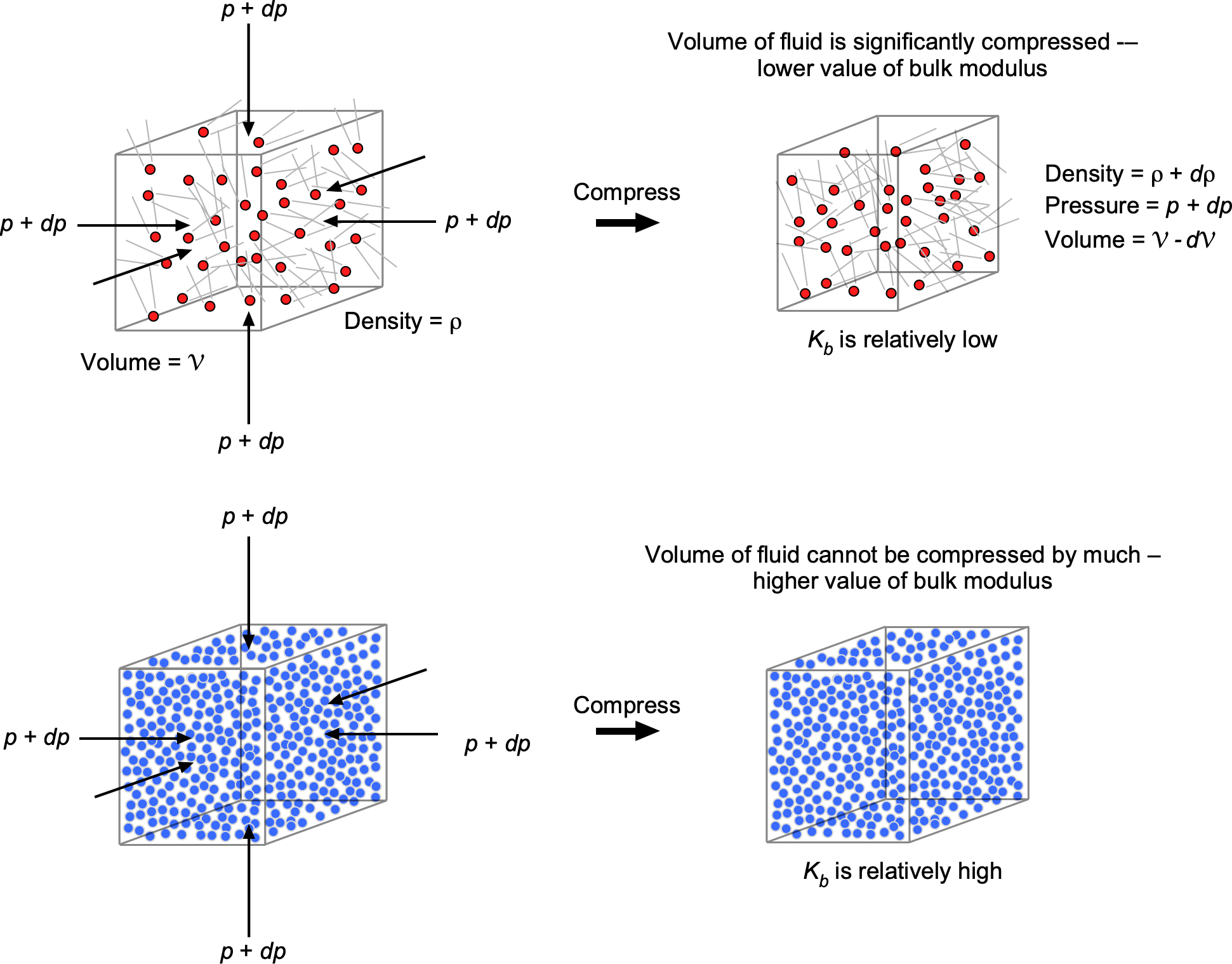

Bulk Modulus

The bulk modulus, denoted by the symbol , measures a substance’s resistance to uniform compression, such as under pressure or some external body force per unit mass. The bulk modulus is equivalent to a compressive “stiffness” and is an essential property in fluid mechanics. In particular, its value is related to the speed of sound propagation in liquids, which plays a fundamental role in various scientific, industrial, and medical imaging[9], and other technological applications[10], where precise measurement and understanding of acoustic properties are crucial.

When a fluid of original volume is subjected to a change in external pressure

, it undergoes a volume change

, the relationship being given by

(28)

where the coefficient is called the bulk modulus. Notice that the minus sign means a positive change in applied pressure will decrease the fluid volume, as illustrated in the figure below. In the limit when the change in pressure becomes infinitesimally small, then Eq. 28 becomes

(29)

Therefore, the bulk modulus is defined as

(30)

Conservation of mass of the fluid volume also requires that

(31)

Expanding out and simplifying gives

(32)

or

(33)

Therefore, the bulk modulus can also be defined as

(34)

In other words, Eqs. 30 and 34 quantify the degree of compressibility of the original volume of fluid under pressure. A high bulk modulus value indicates that the substance is difficult to compress, i.e., it is essentially incompressible. It will also be apparent that the bulk modulus has units of pressure.

Liquids have relatively high values of bulk modulus because their molecules are closely packed together, resisting pressure and other external forces that can cause compression. Indeed, for all practical purposes, liquids cannot be compressed significantly (their values of bulk moduli are in the GPa or Giga-Pascal range), so, with few exceptions, they can be considered incompressible fluids.

Gases have much lower values of bulk modulus because their molecules are farther apart, with larger spaces between them, allowing them to be compressed more easily. In general, gases cannot be considered incompressible fluids, and the bulk modulus of a gas varies with its pressure and temperature. One type of bulk modulus used in practice is the isothermal (i.e., constant temperature system) bulk modulus, , which can be written as

(35)

The isothermal gas law (Boyle’s law) states that constant, so differentiating with respect to

using the product rule gives

(36)

so that

(37)

Substituting this result into Eq. 35 gives

(38)

This means that a gas’s isothermal bulk modulus is its pressure; therefore, its “stiffness” or resistance to compression is directly proportional to its pressure. As the gas’s pressure increases, its resistance to further compression rises proportionally.

If the compression is adiabatic, the gas’s temperature increases because the work done on it increases its internal energy. Conversely, the temperature decreases during adiabatic expansion as the gas exchanges energy with its surroundings, losing internal energy. In an adiabatic process, the relationship between pressure and density is

(39)

Differentiating this equation with respect to using the product rule leads to

(40)

and solving for gives

(41)

Therefore, substituting this previous result into Eq. 34 for an adiabatic process, gives the bulk modulus as

(42)

Fluid Viscosity

The property of viscosity can be viewed as the fluid’s resistance to shear when different parts of the fluid are in relative motion, i.e., its “internal friction” or resistance to being deformed. Viscosity can also be viewed as a measure of fluidity, i.e., the higher the viscosity, the lower the fluidity. The symbol (i.e., the Greek symbol “mu”) is a constant known as the coefficient of dynamic viscosity, or more simply, just the fluid’s viscosity.

All fluids have viscosity to a lesser or greater degree, so for a fluid in relative motion, the property of viscosity causes shear forces to be produced within the fluid. Gases generally have a much lower viscosity than liquids, which is a reasonably obvious expectation. Some liquids are very viscous, such as molasses, corn syrup, grease, and heavy oils. However, the effects of viscosity come into play in the behavior of all types of fluids.

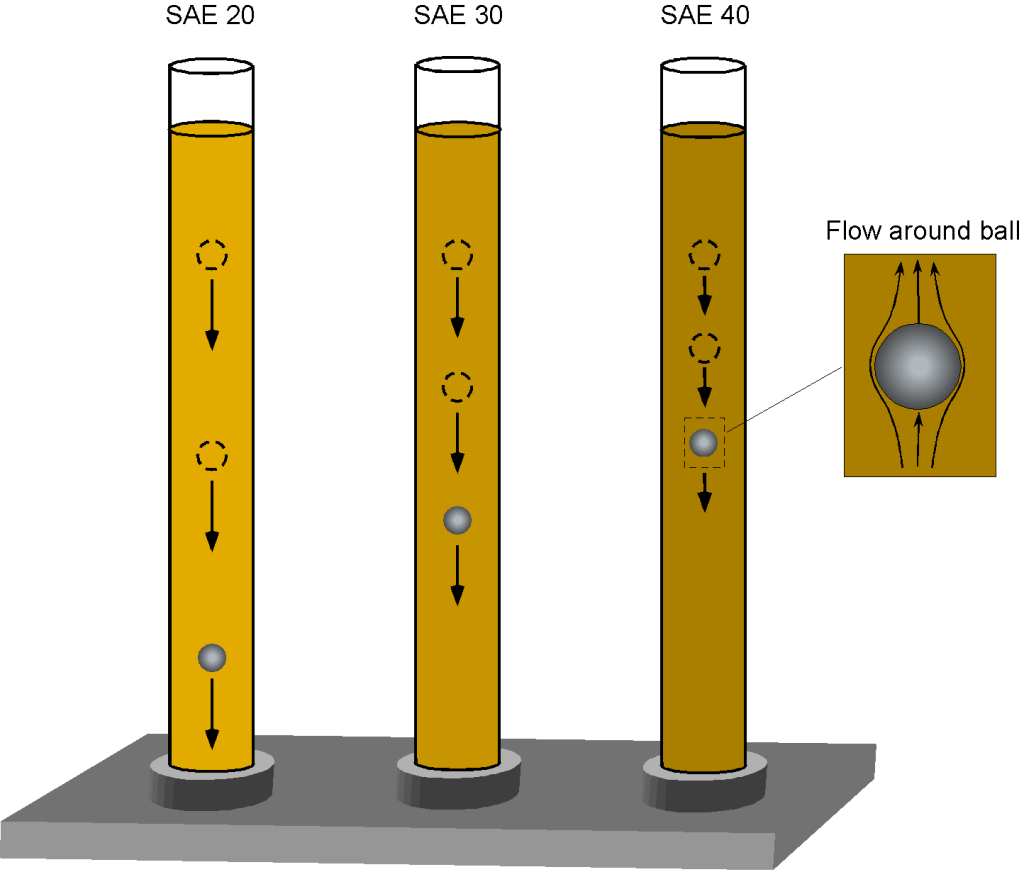

Viscometer

One way to begin understanding the property of viscosity is to consider a demonstration with three columns of oil, as shown in the figure below. Each oil has a different viscosity, ranging from SAE 20 (the thinnest and least viscous) to SAE 40 (the most viscous). SAE stands for the Society of Automotive Engineers. Suppose a heavy steel ball is dropped into the oil. In that case, it will descend at a velocity proportional to its viscosity, as the oil causes shear stresses on the ball’s surface, resulting in a viscous drag as it moves downward under the influence of gravity.

The balance of forces in equilibrium descent is such that the weight of the ball, , less any buoyancy force,

, is equal to the viscous drag on the ball,

. The weight will be density times volume times acceleration under gravity, i.e.,

(43)

where is the density of the steel ball. The (upward) buoyancy force on the ball (Archimedes’ principle) will be equal to the weight of oil displaced by the ball, i.e.,

(44)

Therefore, the equilibrium equation is

(45)

The drag force on a sphere of radius

dropping through a fluid of high viscosity

at low speed

(this is called a creeping flow) is given by Stokes’s law, i.e.,

(46)

where is the viscosity of the fluid. Therefore, in equilibrium, then

(47)

and rearranging to solve for gives

(48)

For a ball of the same weight and size, Eq. 48 shows it will drop in the oil at a velocity that is inversely proportional to the oil’s viscosity, , i.e., the higher the viscosity, the slower the ball drops. The foregoing is the principle used in the falling-sphere viscometer. The time,

, it takes for a steel sphere of known size (radius),

, and weight (material density

), can be measured using two lines on the tube a distance

apart, from which the ball’s velocity,

, is determined. Stokes’s law (Eq. 46) can be used to determine the viscosity,

, of the oil (or other liquid) from the resulting velocity by knowing the size and weight of the sphere as well as the density of the liquid, i.e.,

(49)

How does one measure the viscosity of a gas?

Gases have significantly lower viscosities than liquids. One way to measure a gas’s viscosity is by using a capillary viscometer, a method first used by William Rankine. This technique measures the pressure drop along the length of a narrow capillary tube. A capillary tube is used to ensure the flow is laminar, for which there is an exact theoretical solution for the pressure drop, known as Poiseuille’s law, which is written in terms of the coefficient of dynamic viscosity. Temperature control of the gas flow is significant, but capillary viscometers can provide acceptable viscosity measurements.

Units of Viscosity

Viscosity has units of kg m-1 s-1 or Nm-2s or Pa s (i.e., a Pascal-second often called the Poiseuille, named after Jean Léonard Marie Poiseuille) in the SI system or slug ft-1 s-1 in the USC system. However, the unit of viscosity typically employed in practice is called the “Poise” (P) or gram cm-1 s-1. The unit of poise is 1 Poise = 0.1 Pa s = 1 Poiseuille, i.e., 1 Pa s = 10 Poise. The viscosity of liquids is usually a low numerical value, so it is often reported in units of centipoise (cP). In contrast, the viscosity of gases, which are much less viscous than liquids, is usually reported in units of micropoise (μP). In base units, at MSL ISA then = 1.789 x 10-5 kg m-1 s-1 = 1.789 x 10-5 Pa s = 3.737 x 10-7 slug ft-1 s-1.

Shear in a Fluid

In Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica of 1687, he uses the Latin word tenacitas to mean viscosity. He then defines the concept of viscosity as “Resistentia, quae oritur ex inopia lubricitatis partium fluidi, caeteris paribus, proportionalis est velocitati, qua partes fluidi separantur ab invicem,” which can be translated as “The resistance which arises from the lack of slipperiness originating in a fluid, all other things being equal, is proportional to the velocity by which the parts of the fluid are being separated from each other.”

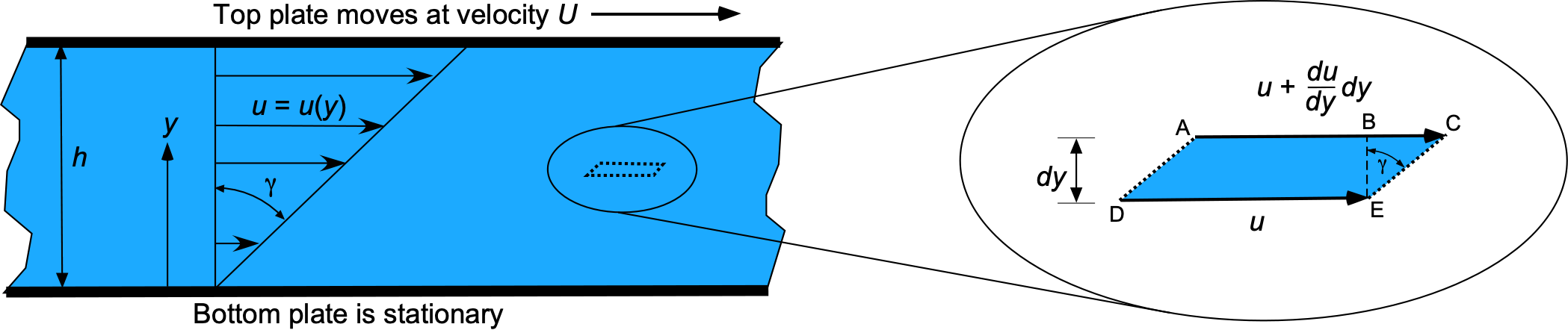

Newton performed experiments similar to the one shown in the figure below, using a fluid of depth between a moving upper plate and a stationary lower plate, i.e., a flow containing a velocity gradient in one direction, with the velocity in the fluid increasing as it moves from one point to another. The upper (faster) layer draws the lower (slower) layer along through a force on the lower layer, so there must be a shear force in the fluid between the layers. Simultaneously, the lower layer tends to exert an equal and opposite force on the upper layer (i.e., Newton’s Third Law).

The fluid next to the bottom plate wants to remain at rest, and the fluid touching the top plate is dragged along (because of viscosity) with a velocity . Consequently, a velocity gradient forms in the fluid between the two plates. Maintaining this gradient requires the application of a force,

, where

(50)

where is the area of the plate. Notice that the ratio

is the slope of the velocity profile or the velocity gradient. In terms of force per unit area, which is a stress,

, then

(51)

where the constant of proportionality, , is the “resistance to shear,” i.e., the fluid’s viscosity.

In general, for the straight and parallel motion of a given fluid, the tangential stress produced between two adjacent fluid layers is proportional to the velocity gradient in a direction perpendicular to the layers, i.e.,

(52)

where is the velocity at some distance

. The quantity

is the

velocity gradient in the

direction. The velocity gradient

is equivalent to a strain rate, so this preceding equation is just a statement of a fluid’s linear stress/strain rate relationship. Equation 52 is called Newton’s law of viscosity. Remember that maintaining a velocity gradient and the shear stresses in a fluid requires continuous application of a force; if the force were to stop, the fluid would stop deforming, and the shear stresses would become zero.

To explain this latter point further, consider a fluid element as it flows in a fluid with a velocity gradient, as shown in the right-side figure above. If is positive, then the upper surface of the element will move faster than the lower surface, so over some time

, the upper AC surface will travel further than the lower surface DE by a distance

(53)

Consequently, a shear deformation or strain is produced in the fluid. This strain can be calculated from the geometry of the deformation shown in the figure above. The strain, , which is the angle between the lines EB and EC, is

(54)

to a small-angle approximation. Rearranging the equation gives

(55)

and so the shear stress in the fluid is

(56)

This latter result is another way of writing Newton’s law of viscosity. Notice that the shear stress depends on the strain rate, i.e., . Remember that the shear stress in a solid is proportional to strain, so a constantly applied strain will create constant deformation and stress. In a fluid, however, shear stress is only produced by a strain rate because the fluid continuously flows and deforms.

Velocity Gradients & Shear Stresses

Newton’s law of viscosity should be written more precisely using the partial derivative on the velocity gradient, i.e., it should be written as

(57)

because the velocity in a fluid may vary in other directions as well, e.g., the flow is three-dimensional, so there could be

velocity gradients in the

and

directions, i.e.,

, and

. In general, these gradients can be written in the matrix (or tensor) form as

(58)

The velocity gradient tensor is diagonally symmetric, meaning that the cross-derivatives are related, i.e., ,

, and

. This symmetry reduces the number of unique velocity gradients from nine to six, so the shear stress tensor becomes

(59)

and in component form, then

(60)

This is a significant result used to derive the momentum equation for a fluid, the Navier-Stokes equation. Notice that the diagonal terms in the stress tensor are called normal compressive stresses because they act perpendicular (or normally) to the respective surfaces. The off-diagonal terms are shear stresses, which act tangentially to the surfaces.

What is kinematic viscosity?

Dynamic viscosity is a measure of shear resistance, i.e., viscosity only matters in the presence of motion or dynamics. In many fluid problems involving viscosity, the magnitude of the viscous forces compared to the magnitude of the inertia forces is critically important; that is, the forces causing an acceleration of the fluid. Because the viscous forces are proportional to and the inertia forces are proportional to

, the ratio of

is often involved in solving the problem. This ratio of

to density

is called the kinematic viscosity and given the symbol

(Greek symbol “nu”), i.e.,

Therefore, kinematic viscosity is a derived parameter. Kinematic viscosity values have units of ms

in the SI system or ft

s

in the USC system.

Mechanisms of Viscosity

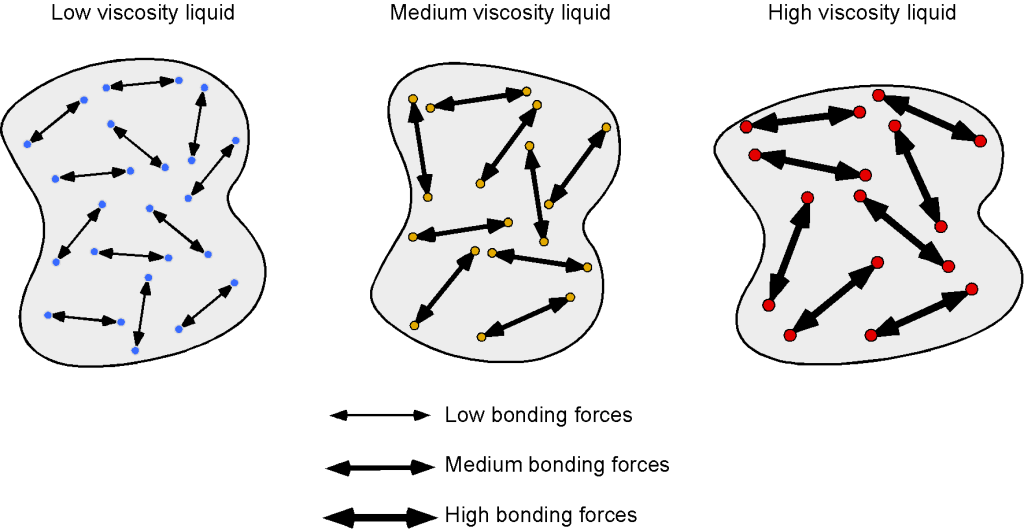

The viscous properties of a fluid arise from two sources: 1. Intermolecular momentum transfer between the molecules, and 2. Bonding between the molecules. Therefore, the viscosity of a fluid depends on whether it is a gas or a liquid; its characteristics primarily depend on the physics associated with the mean relative spacing between its molecules.

The molecules in a liquid are relatively close together, but they are not as mobile as those in a gas. In this case, viscosity results more from molecular bonding and less from intermolecular momentum transfer. As shown in the schematic below, stronger bonding results in higher resistance to deformation, i.e., higher viscosity. In general, intermolecular bonding can be influenced by factors such as the size, molecular weight, strength of the bonds, and temperature of the liquid.

For example, liquids with large, heavy molecules tend to have a higher viscosity than liquids with small, light molecules because the larger molecules have more intermolecular bonds and are more resistant to flow. Liquids such as benzene, diethyl ether, gasoline, ethanol, and water flow very readily because of their low viscosity. Others, such as honey, heavy oils, glycerin, motor oil, molasses, and maple syrup, flow very slowly and have a high viscosity. There is also a correlation between viscosity and molecular shape. Liquids of long, flexible molecules tend to have higher viscosities than those of more spherical or shorter-chain molecules. The longer the molecules, the easier it is for them to become “tangled” with one another, increasing the viscosity of the liquid.

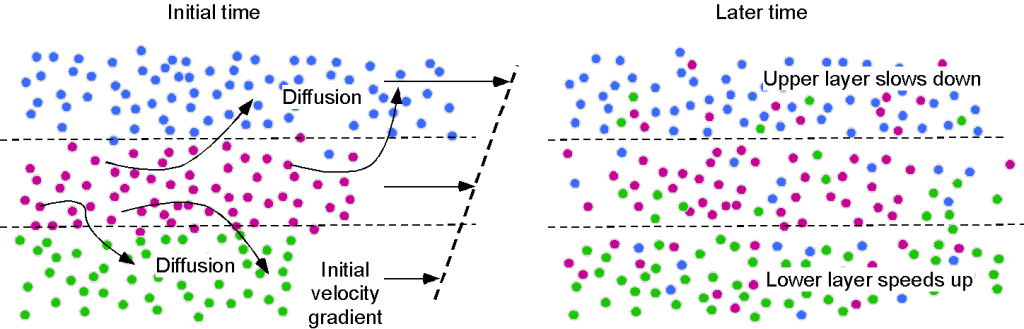

The intermolecular bonding is much lower because the molecules in a gas are farther apart. The mechanism of viscosity results from intermolecular momentum transfer as the fairly mobile molecules diffuse throughout the gas. Nevertheless, gases are still viscous and exhibit the characteristics of viscosity. This effect becomes more apparent when the gas has an initial velocity gradient, as shown in the schematic below.

The random motion of gas molecules between fluid layers means that collisions inevitably occur, and momentum is exchanged, whereby slower molecules gain momentum from the faster molecules. The consequence of intermolecular momentum transfer is a shear force between the gas layers in regions of velocity gradient, resulting in resistance to further deformation, which manifests as viscosity. Remember that fluids must be continuously deformed to produce stresses, so in the absence of any additional shear rates, the velocity gradients will diminish as the momentum interchange balances throughout the layers of the gas.

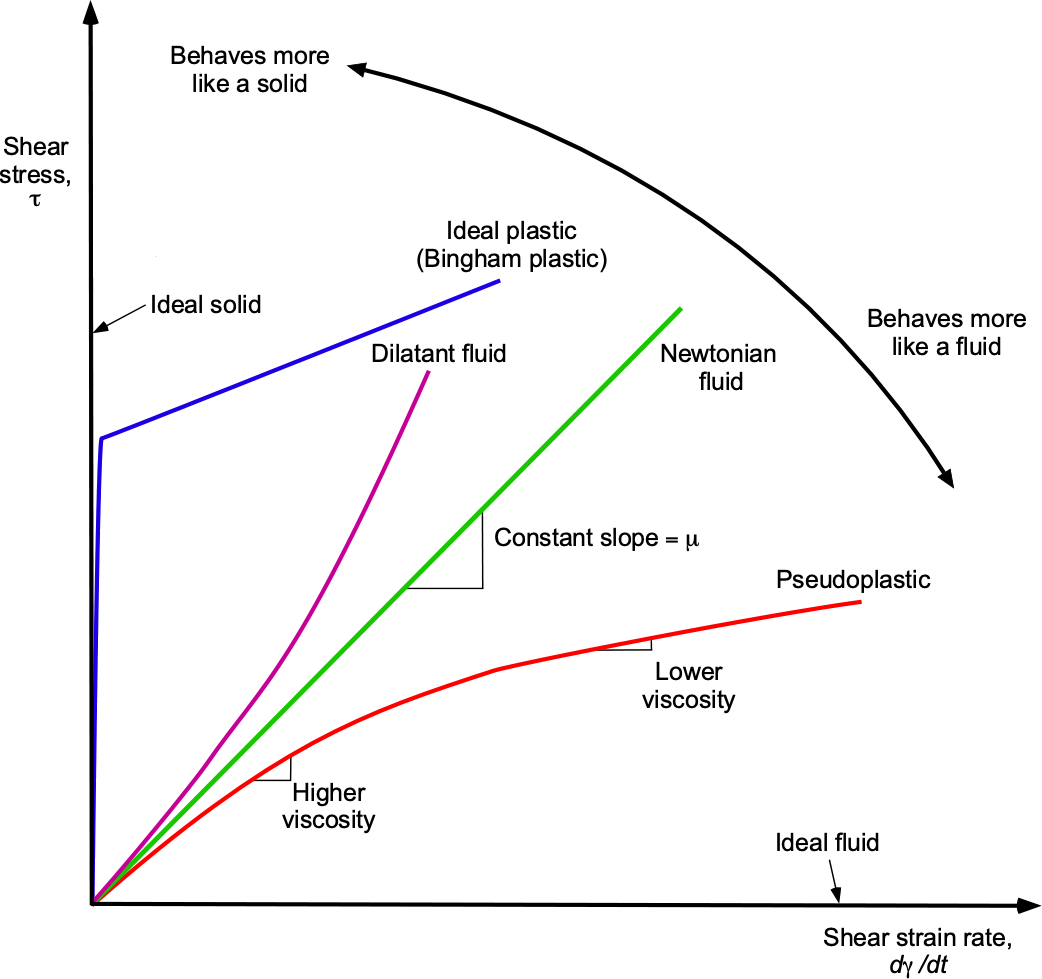

Newtonian Versus Non-Newtonian Fluids

A Newtonian fluid is a fluid in which the value of is constant and independent of the strain rate (i.e.,

is independent of the magnitude of the velocity gradient). Many fluids, including air and water, behave as Newtonian fluids, i.e., they obey a linear stress-strain relationship, as shown in the figure below. Therefore, the value of

can be assumed to be constant. Remember that in a fluid, the shear stresses produced by viscosity are directly related to the strain rate generated in the fluid by its deformation.

However, not all fluids behave in this linear way. For example, fluids such as certain oils, blood, inks, and most paints exhibit non-Newtonian behavior, where their viscosity changes as a function of the strain rate. The viscosity may increase or decrease with an increasing strain rate, depending on the nature of the fluid. For example, a dilatant fluid experiences shear thickening, and a pseudoplastic fluid exhibits shear thinning. The behavior of such non-Newtonian fluids is less well understood, making their behavior less predictable; however, they have numerous practical applications. For example, paints behave as pseudoplastic fluids, which thin when mixed or agitated during brushing or spraying. After application, the paint thickens, preventing it from running off the surface. The study of non-Newtonian fluids is called rheology. Conventional methods cannot be used to measure the viscosity of a non-Newtonian fluid. Instead, it is necessary to measure the apparent viscosity, which considers the shear rate at which the viscosity measurement was made.

Why is ketchup so hard to get out of the bottle?

Ketchup is infamous for being difficult to remove from a bottle unless you know the secret. Shake it first! In the bottle, ketchup is a reasonably viscous fluid and does not pour easily because of the relatively strong cohesive bonding between the ketchup molecules, which includes various polymer chains. To liquefy ketchup, vigorously shake the bottle, which agitates and deforms the fluid, creating a strain rate. This process also stretches the polymer molecules, allowing them to experience less cohesive bonding and, consequently, reduced viscosity. The process takes a few seconds, but you can easily pour the ketchup onto your burger. Today, ketchup often comes in squeeze bottles, in which the ketchup is forced through an orifice by creating pressure in the bottle. This process also creates a strain rate, which reduces the viscosity of the ketchup, allowing it to be poured. After this point, the ketchup thickens again, so it doesn’t run off your burger!

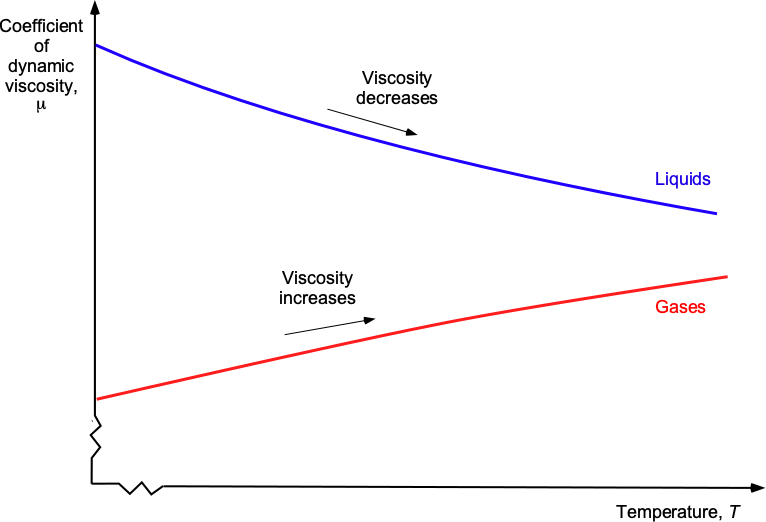

Effects of Temperature on Viscosity

Temperature has a significant impact on the viscosity of both gases and liquids. Consequently, the viscous characteristics of gases change differently from liquids when subjected to changes in temperature, as shown in the figure below. For example, the viscosity of a liquid generally decreases with increasing temperature. This effect occurs because the reduction in bonding forces, as the motion of the molecules causes them to move further apart, dominates over any increase in intermolecular momentum transfer. Consequently, liquids become less viscous and flow more easily as the temperature increases. However, gases, including air, typically exhibit increased viscosity with increasing temperature because of the increase in intermolecular momentum transfer, which increases the resistance to the fluid’s deformation.

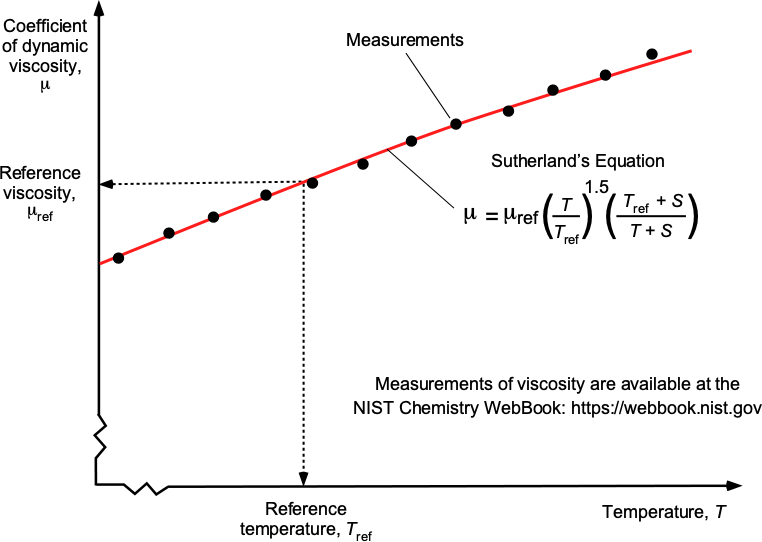

Sutherland’s Law of Viscosity for Gases

The coefficient of dynamic viscosity, (or often referred to as the coefficient of viscosity or viscosity), for a gas can be calculated using Sutherland’s formula or Sutherland’s law. This empirical (i.e., experimentally derived) law was first published in 1893 and can be written as a function of absolute temperature,

, as

(61)

where reference values (subscript “ref”) are in appropriate SI or USC units. The parameter is known as Sutherland’s constant. A graphical interpretation of Sutherland’s law is shown in the figure below.

For air in SI units, then = 323

K are

kg m

s

(also known as units of Pa~s), with a Sutherland constant of

= 110.0

K. In USC units at

= 518.67

R, then

= 198.72

R and

slugs s

ft

. Coefficients for other gases are widely available in reference books and online data sources.

Sutherland’s law is widely used in various engineering fields to predict the viscosity of gases at different temperatures. It operates over a wide range of temperatures for air and gases, including oxygen, nitrogen, and helium. However, it is essential to note that it is not universally applicable to all gases. For example, Sutherland’s law does not apply to gases that exhibit significant deviations from ideal behavior, such as rarefied gases or gases containing large molecules. Additionally, Sutherland’s law does not apply to liquids, which exhibit a more complex relationship between viscosity and temperature because of the effects of intermolecular bonding. In general, Sutherland’s law should be used cautiously, and its applicability should be verified for each specific gas and temperature range of interest.

Check Your Understanding #3 – Calculating the value of viscosity

If a measurement in air gives a temperature of 52F, calculate the dynamic viscosity coefficient. Hint: Use Sutherland’s Law. What happens to the viscosity of air as its temperature increases, and why?

Show solution/hide solution.

Sutherland’s Law can be expressed as

where R,

R and

slugs s

ft

. In this case, the absolute temperature is

Inserting the values gives

Therefore,

Bonding between molecules in a gas is relatively low compared to that in a liquid. Therefore, the intermolecular momentum transfer between the molecules increases more with increasing temperature, which manifests as an increase in viscosity.

No, a shock wave in air does not cause air to become a non-Newtonian fluid. Air remains a Newtonian fluid even under the relatively extreme conditions of shock wave formation. As we discussed in class, a Newtonian fluid is defined by its linear relationship between shear stress and shear rate, which means its viscosity remains constant regardless of the applied stress. In contrast, non-Newtonian fluids have a non-linear relationship, meaning their viscosity can change with the applied stress. A shock wave in air causes a sudden and significant pressure, temperature, and density increase. Basically, the air is squeezed into a narrow wavefront. However, the molecular structure and the basic properties of air remain the same, and the air continues to behave as a Newtonian fluid. The viscosity of air may change with temperature, which can be quantified using Sutherland’s law, but this change is consistent with the behavior of a Newtonian fluid.

Temperature Effects on the Viscosity of Liquids

The Andrade equation, named after British physicist Edward Andrade, is a commonly used semi-empirical model to predict the effects of temperature on the viscosity of liquids. This equation relates the viscosity of a liquid to temperature based on an exponential relationship, i.e.,

(62)

where is the viscosity of the liquid and

is the absolute temperature, and the coefficients

and

depend on the liquid. Values of

and

for this two parameter model are widely published for many liquids. This equation represents the behavior that viscosity decreases with increasing temperature for a liquid.

There are also other semi-empirical models for the effects of temperature on the viscosity of liquids. The three-parameter model is

(63)

and the four-parameter model is

(64)

Again, the coefficients, A, B, C, and D for most liquids can be found in published sources.

What does it mean when my car needs to use 20W50 engine oil?

Engine oils are classified by their viscosity grades, designated by numbers such as SAE 5 to SAE 50 or higher; the higher the number, the higher the viscosity (thicker oil). Using a single-grade oil, such as SAE 50, can lead to problems in extreme temperature conditions. The oil must maintain adequate viscosity at high temperatures to provide sufficient lubrication and prevent engine wear. However, a highly viscous oil like SAE 50 can become too thick at low temperatures and may not properly lubricate the engine components. To address these temperature-related issues, most modern oils are formulated as multigrade oils denoted by a combination of two numbers, such as SAE 20W50. The “W” represents winter and indicates the oil’s viscosity at low temperatures. The oil has an SAE 20 oil viscosity at lower temperatures, providing better initial lubrication of the engine parts. At higher temperatures, it maintains the viscosity of an SAE 50 oil to offer adequate lubrication. This characteristic involves blending additives into the base oil that modify the intermolecular interactions and control its temperature-dependent viscosity.

Flow Velocity

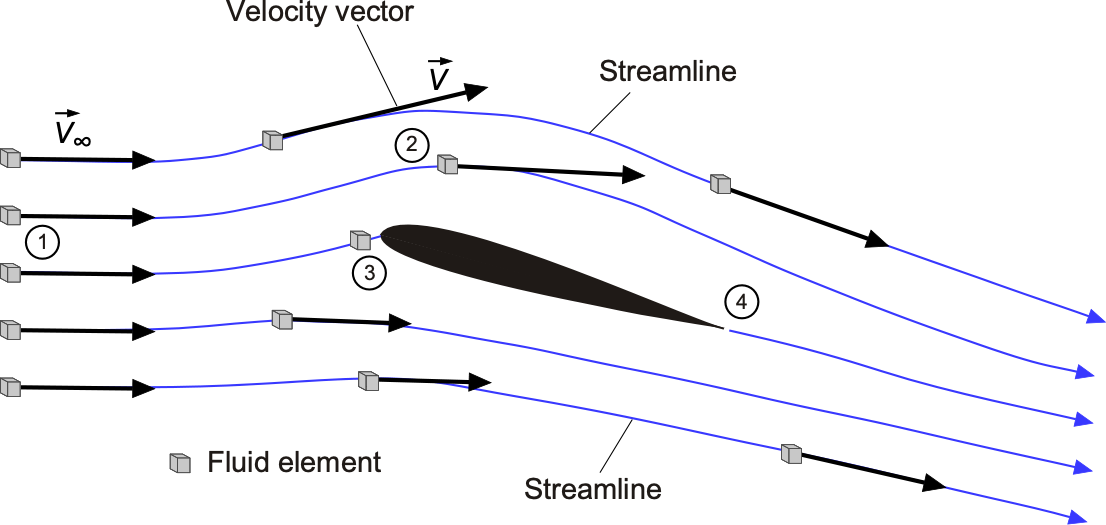

In fluid mechanics, a primary focus is on fluids in motion, called fluid dynamics. Hence, the velocity of the fluid is a significant quantity that must be defined carefully. By definition, a velocity is a vector quantity, so the velocity of any given fluid packet will have both a magnitude (a speed) and a direction. When the concept of the velocity of a fluid is considered, which will have relative motion between the fluid packets, then its velocity becomes more subtle to describe than for a solid body where all the parts will move in unison.

For example, for a solid body in translational motion, it is evident that all points of the body will be traveling at the same velocity, i.e., with the same speed and direction. However, different parts of a fluid in motion will most likely travel at varying velocities so that they will be in relative motion. This is just one reason why the motion of fluids is somewhat more challenging to describe, both physically and mathematically.

Tracking where the fluid moves in space and time is essential to understanding flow problems, allowing one to visualize where the flow goes as it passes around an airfoil or other object. Consider the flow about an airfoil at a steady angle of attack and follow the path of a small group of fluid particles initially upstream of the airfoil at point 1, as shown in the figure below. This group is called a fluid element because it is a small elemental flow volume. The speed and direction of the fluid elements will change as they move downstream from point 1 to points 2 and 3, point 3 being nearer to the nose of the airfoil. Point 3 at the nose is called a stagnation point because the air is brought to rest there and stagnates. Therefore, the flow velocity at 1 or 2 or 3, or any other point in the field, is just the velocity of an infinitesimally small fluid element as it passes through that point. The flow passes around the airfoil and leaves it at point 4. In this case, the paths that the fluid elements follow are also called streamlines, although the distinction between streamlines, pathlines, and streakliness is still to be made.

Velocity has magnitude and direction, but it is still a point property in that its value will change from point to point in the flow, and it can also change with respect to time, i.e., . Flow velocities are measured in units of m s

in the SI system or ft s

in the USC system.

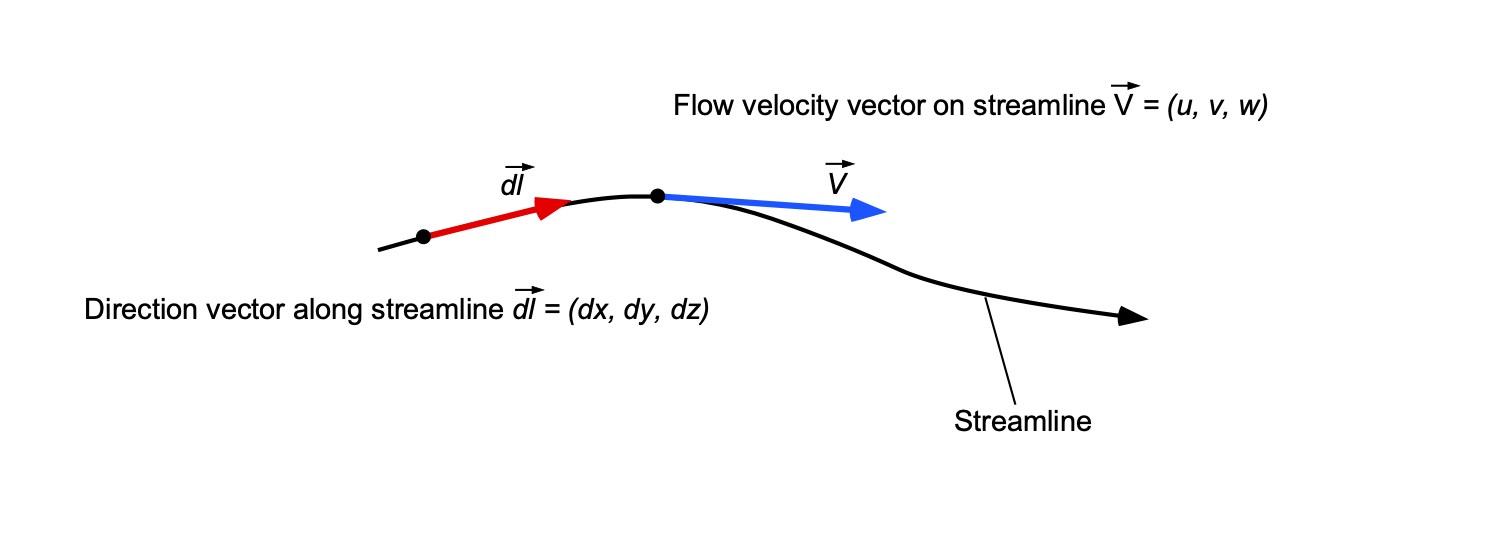

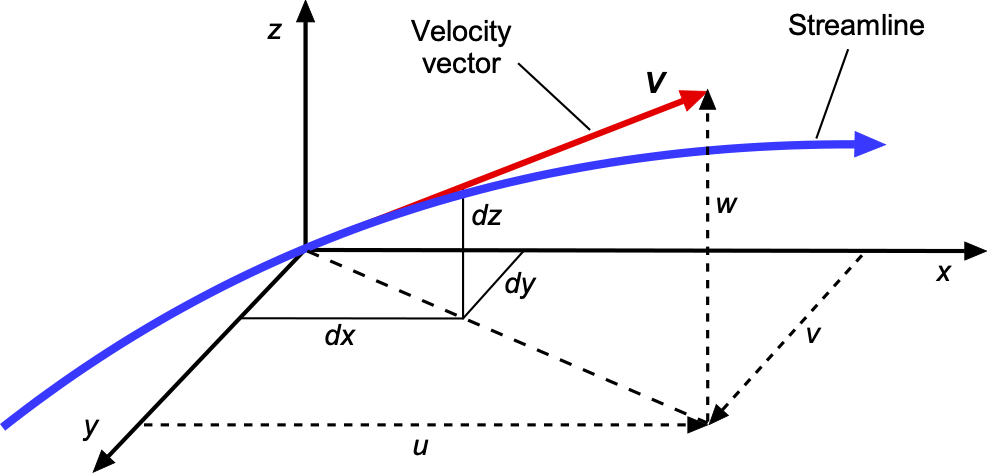

Equation of a Streamline

The equation of a streamline is straightforward to determine. For a two-dimensional flow in the –

plane, then

so the slope of a streamline is just

, which is an ordinary differential equation. Therefore, this differential equation could be solved with the known velocity field to trace a streamline in a given plane. In three-dimensions, i.e., in

,

and

space then

. In this case, a direction vector, say

, can be defined that points along the streamline, i.e., in a direction parallel to the streamline, as shown in the figure below.

By definition, there is no flow across a streamline, so the equation of a streamline in three-dimensional space is just

(65)

noting that is the zero vector.

The meaning of this latter equation becomes clearer by expanding out the vector equation in terms of its scalar components, i.e.,

(66)

In terms of the components, then

(67)

which can be physically interpreted from the figure below. Therefore, it will be apparent that the equation of a streamline is

(68)

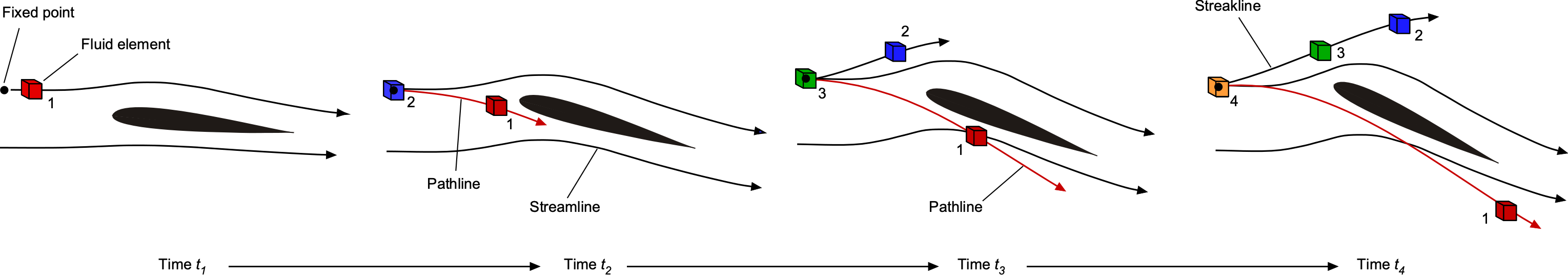

Streamlines, Pathlines & Streaklines

As previously discussed, by definition, a streamline is a line drawn tangential to the instantaneous local velocity vector field, i.e., there is no flow perpendicular to a streamline. Streamlines can be considered an instantaneous realization or “snapshot” of the flow. A pathline is the trajectory or path a fluid element traces out in time, i.e., following the path of the fluid element as it moves through the flow. A streakline is the locus of fluid elements that have passed through the same point in the flow.

In general, streamlines are different from both pathlines and streaklines. In steady flow problems, when the flow properties do not change with respect to time, called a steady flow, then streamlines, pathlines, and streaklines are all one and the same. In an unsteady flow, the path followed by a fluid element, i.e., the pathline, is not the same as the streamline, as shown in the figure below. At each instant in time, the airfoil reaches a new angle of attack to the flow, and the streamline pattern changes. The fluid element, however, moves along its own pathline as it traces its way through the flow. This is why streamlines are referred to as an instantaneous realization or snapshot of the flow. In contrast, the pathlines and the streaklines depend on the prior history of the velocity field.

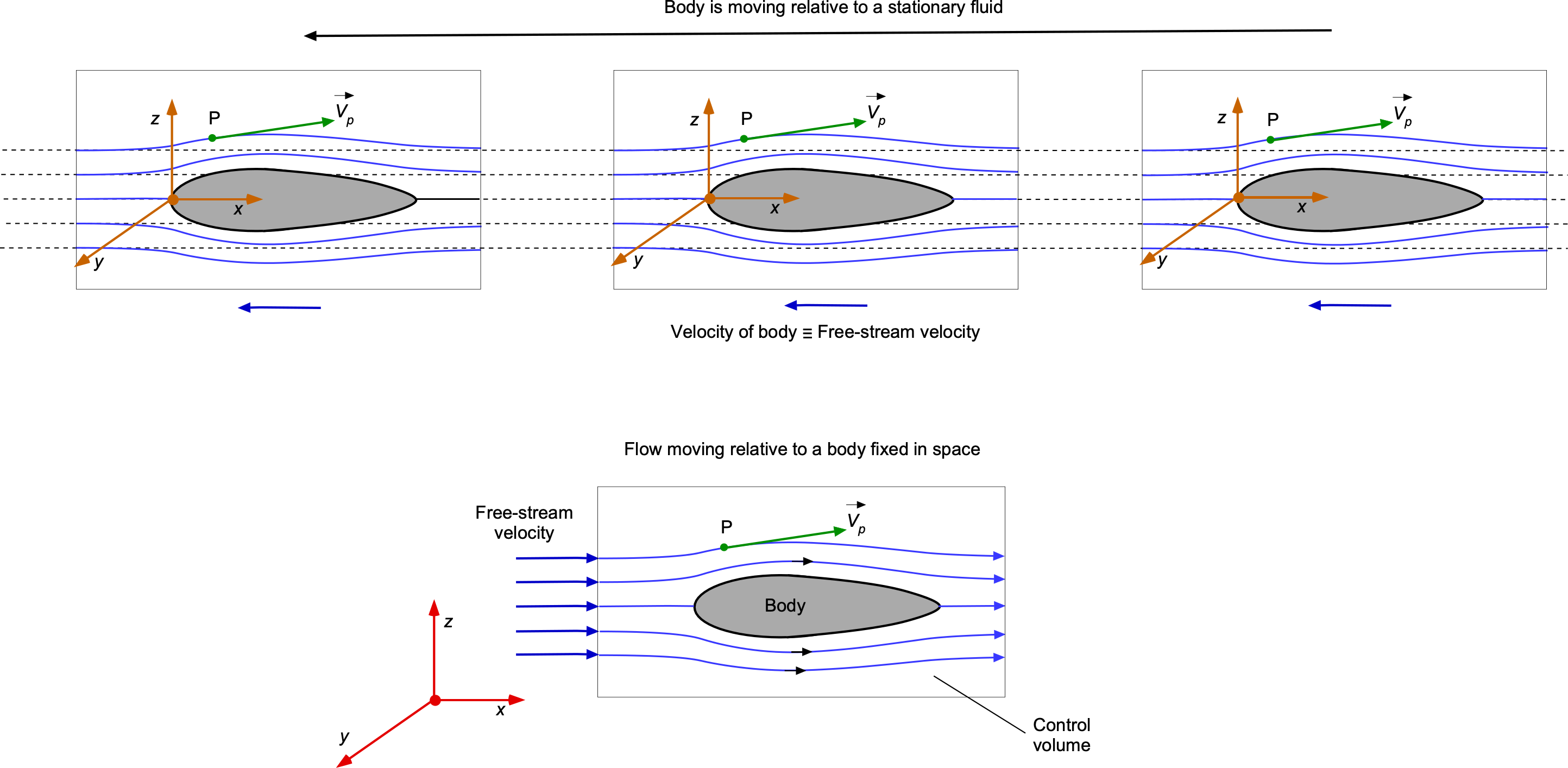

Frames of Reference

An interesting issue in fluid dynamics and the calculation of streamlines is the frame of reference. The question usually is: Is the body moving in a stationary flow, or is the flow moving past a stationary body, and are they equivalent? The answer lies in the frame of reference.

One frame of reference is to think of a moving body in stationary flow, as shown in the figure below. In this frame of reference, the airfoil moves through the air, which is considered undisturbed and stationary. The other frame of reference, a stationary body in a moving flow, is a typical setup for wind tunnel testing, theoretical analyses, and numerical simulations. In this frame, the airfoil is stationary, and the air flows past it. This setup is also used because it simplifies the boundary conditions and problem setup. Notice, however, that the streamline patterns will be different in each case. In the case of a stationary body, an observer will see the same streamline pattern for all time. In the case of the moving body, an observer will see that the initially stationary flow will see a streamlined pattern develop and then return to its undisturbed state, i.e., the observer views the behavior as an unsteady flow.

Mathematically, both frames of reference are equivalent because of the principle of relativity for non-accelerating frames. This means the physical phenomena observed or measured, such as lift, drag, and pressure distribution, will be the same regardless of whether the airfoil moves through the air or the air moves past the airfoil. However, the choice of frame can affect the complexity of the analysis and the implementation of numerical methods.

Check Your Understanding #4 – Calculating the equation of a streamline

If a two-dimensional velocity field in the –

plane is defined as

, then what are the mathematical equations of the streamlines?

Show solution/hide solution.

In this case, the governing equation for the streamline is

Separating the variables and integrating them gives

where is a constant, so then

or just

which, for different values of , are concentric circular streamlines centered around the origin.

In a more general sense, the streamline equations are often solved using a parameter , which can be thought of as time or another parameter that varies along the length of a streamline, i.e.,

(69)

To find the streamline, integrate each equation with respect to , i.e.,

(70)

(71)

(72)

where is the starting point of the streamline at

.

Numerical integration methods available include Euler’s method, Runge-Kutta methods, etc. Second-order Runge-Kutta methods are commonly used to calculate streamlines. If the time step is small enough, an explicit Euler method will be sufficient for calculating the streamlines in two dimensions. For example, for the component, a one-step explicit method for a given time step

is of the form

and for the component

where represents the current time step and

represents the next time step. This algorithm is easily programmed, and if

and

are given as some simple function of

and

, then the streamlines can be solved. However, the value of

must be small enough to prevent errors from accumulating in the values of

and

, and some trial and error may be involved. Some trial and error may also be needed to find suitable initial points to integrate from so that the nature of the flow field becomes apparent.

MATLAB has various solvers for initial value problems for ODEs and can be used to trace pathlines and streamlines in simple flows; an example is shown below. However, the accuracy of the streamline calculations depends strongly on the spatial and quality of the velocity field that can be calculated or measured and not just the accuracy of the numerical method.

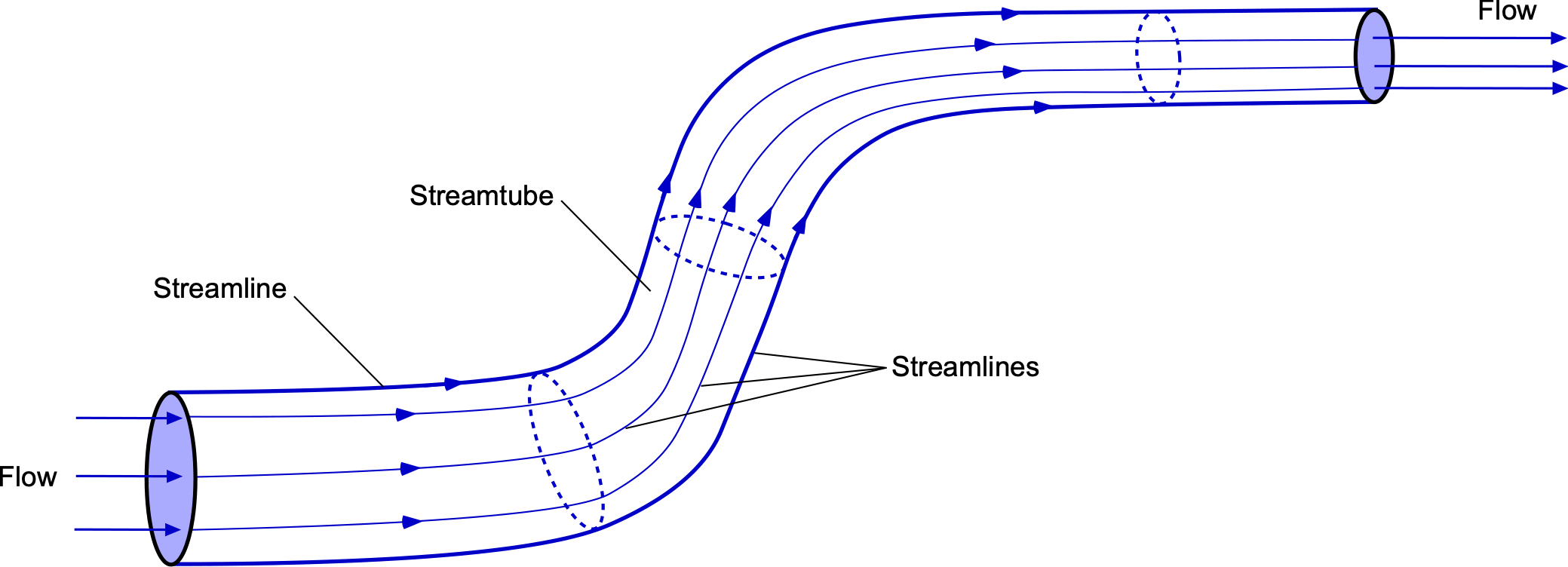

Streamtubes

A streamtube is a concept used in fluid dynamics to represent a bundle of streamlines. These streamlines delineate the boundaries of a particular flow or control volume as a tubular structure, as shown in the figure below. Within a streamtube, the mass flow rate of fluid entering one end must equal the mass flow rate exiting at the other end by the principle of conservation of mass. This means that the mass flow rate within the boundaries of the streamtube is constant; there is no mass flow over the boundaries of a streamtube. Streamtubes are often considered axisymmetric flows in that the fluid properties are radially symmetric or uniform at any one section. A uniform axisymmetric flow through a streamtube is a common assumption when learning fluid dynamics.

Speed of Sound in Fluid Media

The speed of sound in any medium depends on how quickly vibrational energy can be transferred from molecule to molecule through the medium. All gases are compressible, so pressure disturbances produced at one point will quickly propagate to another point but at a finite speed. This propagation speed is called the speed of sound, given the symbol , and its value differs from gas to gas. Sound waves oscillate very rapidly, causing compressions and rarefactions in the medium. The time scale for these oscillations is usually so short that there is insufficient time for significant heat exchange with the surroundings, making the process thermodynamically reversible. Therefore, sound propagation can be assumed adiabatic.

Speed of Sound in a Gas

It can be shown, in general, that the speed of sound is related to changes in pressure and density of the fluid medium using

(73)

For an adiabatic process, then

(74)

where is the ratio of specific heats, i.e.,

. In the compression and rarefaction of a gas, the sound waves occur so quickly that they can be considered adiabatic processes; the rapid oscillations of pressure and density do not allow significant heat exchange. Solving for

gives

(75)

so that

(76)

using where

is the specific gas constant. Therefore, the speed of sound in a gas depends on the gas type and the absolute temperature of that gas.

Because liquids and solids are very difficult to compress and change their density, the speed of sound in such media is generally greater than in gases, e.g., sound travels about four times faster in water than in air. Notice that the values of and

differ for different gases; a useful table is given below.

| Gas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 1.4 | 287.05 | 1717.0 |

| Nitrogen | 1.4 | 296.8 | 1775.0 |

| Hydrogen | 1.41 | 4124.2 | 24663.0 |

| Helium | 1.66 | 2077.1 | 12421.0 |

| Oxygen | 1.395 | 259.84 | 1554.0 |

| Carbon Dioxide | 1.289 | 188.92 | 1130.0 |

| Carbon Monoxide | 1.4 | 296.84 | 1775.0 |

Caution should be exercised to ensure that in equations involving the gas constant , the value of

is not only for the correct gas but also in the appropriate engineering units. For air the gas constant,

, is 286.9 J kg

K

in the SI system and 1716.49 ft lb slug

R

in the USC system. Also,

= 1.4 for air, which is non-dimensional.

Check Your Understanding #5 – Calculating the speed of sound in a gas

At 300C, estimate the speed of sound in (a) nitrogen, (b) hydrogen, and (c) helium. Hint: The ratio of specific heats and the gas constants for these gases are listed in the table above.

Show solution/hide solution.

(a) For nitrogen, ,

J kg

K

, and

C

K.

(b) For hydrogen, ,

J kg

K

, and

K.

(c) For helium, ,

J kg

K

, and

K.

Doppler Effect

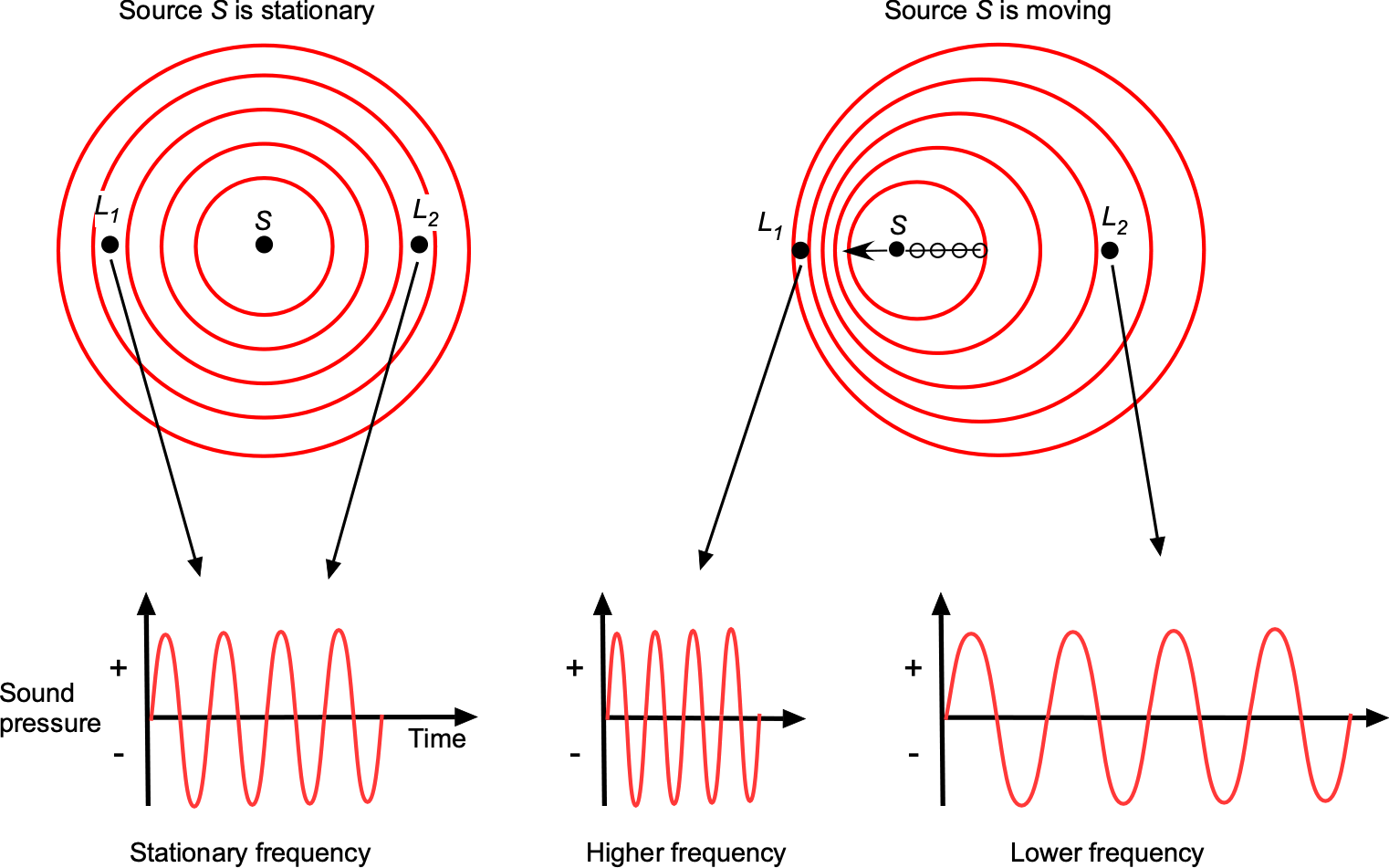

Sound is a pressure disturbance, and the speed of sound propagation in any gas at a given temperature will be constant. Let the frequency of the sound source be , which will be the frequency of the sound heard by any listener if the sound source is stationary. However, the perceived frequency of sound propagation will change if the location of the sound source S and the listener locations (comparing locations L1 and L2) are in relative movement to each other, which is known as the Doppler effect, as illustrated in the figure below.

The frequency , heard by the listener is given by

(77)

where and

are the relative velocity and Mach number of the source, respectively, and

and

are the relative velocity and Mach number, respectively, of the listener, and

is the frequency of the sound source. It is important that the correct signs are used on

and

. If

(listeners are stationary), then the value of

will be positive if the sound source moves away from the listener, and

will be negative if the source moves toward the listener. Therefore, as shown in the figure above, the listener at

ahead of the sound source will hear a higher frequency than the listener at

who is behind the sound source.

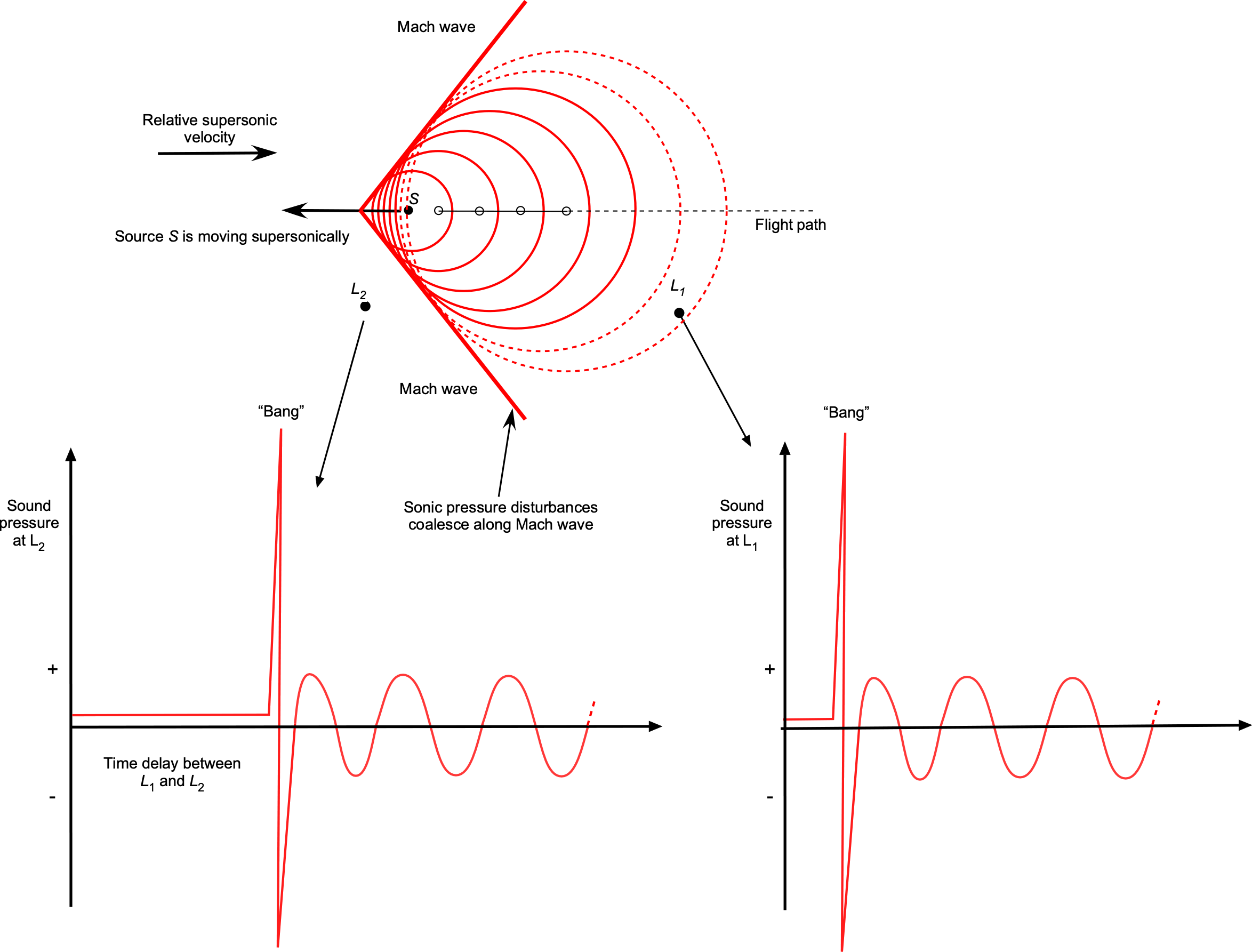

Notice that when the sound source starts to move supersonically, i.e., when , the frequency becomes infinite, which means that the sound becomes concentrated over a wavefront, known as a Mach wave. In three dimensions, this wavefront is called a Mach cone. In this case, a listener upstream of the sound source would not hear it coming until this Mach cone reaches the listener, in which case there would be a loud “bang” as it passes by, as shown in the figure below.

In this case, the lower frequency heard by a stationary listener after the passage of the sound source traveling at a Mach number of will be

(78)

The speed of sound is critical for all flight vehicles, which create pressure disturbances as they fly. The airspeed of an aircraft relative to the speed of sound affects the flow physics and the forces produced on the aircraft, this ratio being called the flight Mach number, . If the aircraft flies much slower than the speed of sound, the conditions are said to be subsonic, and compressibility effects are minor. However, if the aircraft moves faster and approaches or exceeds the speed of sound, called supersonic, compressibility effects become essential, and the flow physics will change. In this case, the issue of the “sonic boom” generated by the aircraft also becomes a consideration for people on the ground.

Speed of Sound in a Liquid

The speed of sound in a liquid varies depending on the type of liquid and its properties, including its density, , and its bulk modulus,

. The speed of sound in a liquid can be calculated using

(79)

where the bulk modulus of the liquid, which, as previously explained, is a measure of its incompressibility. Equation 79 is often referred to as the Newton-Laplace equation.

Sound travels much faster in media with higher values of bulk modulus because it more readily transmits pressure changes. For example, the speed of sound in freshwater at average room temperature is approximately 1,482 m/s ( 4,850 ft/s). The speed of sound in seawater is generally higher because of the presence of salts and minerals, averaging around 1,533 m/s (

5,029 ft/s) at similar temperatures. In general, the speed of sound can vary widely in different liquids; e.g., in ethanol, it is around 1,160 m/s (

3,807 ft/s), and in mercury, it is about 1,450 m/s (

4,760 ft/s). For reference, some numerical values of the bulk modulus for liquids are given in the table below, and others are available online or at other authoritative sources. Notice that bulk modulus has units of pressure. However, it should be appreciated that the temperature and impurities in the liquid can also affect its speed of sound.

| Liquid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater | 1,000 | 62.4 | ~1,482 | ~4,850 | ||

| Seawater | 1,025 | 64.0 | ~1,533 | ~5,029 | ||

| Ethanol | 780 | 49.2 | ~1,160 | ~3,807 | ||

| Mercury | 13,600 | 849 | ~1,450 | ~4,760 | ||

| Glycerol | 1,260 | 78.7 | ~1,920 | ~6,299 | ||

| Benzene | 876 | 54.7 | ~1,280 | ~4,200 | ||

| Methanol | 792 | 49.4 | ~1,100 | ~3,609 | ||

| Olive oil | 920 | 57.4 | ~1,370 | ~4,485 | ||

| Acetone | 790 | 49/3 | ~1,210 | ~2,964 | ||

| Carbon tetrachloride | 1,590 | 99.3 | ~930 | ~3,051 |

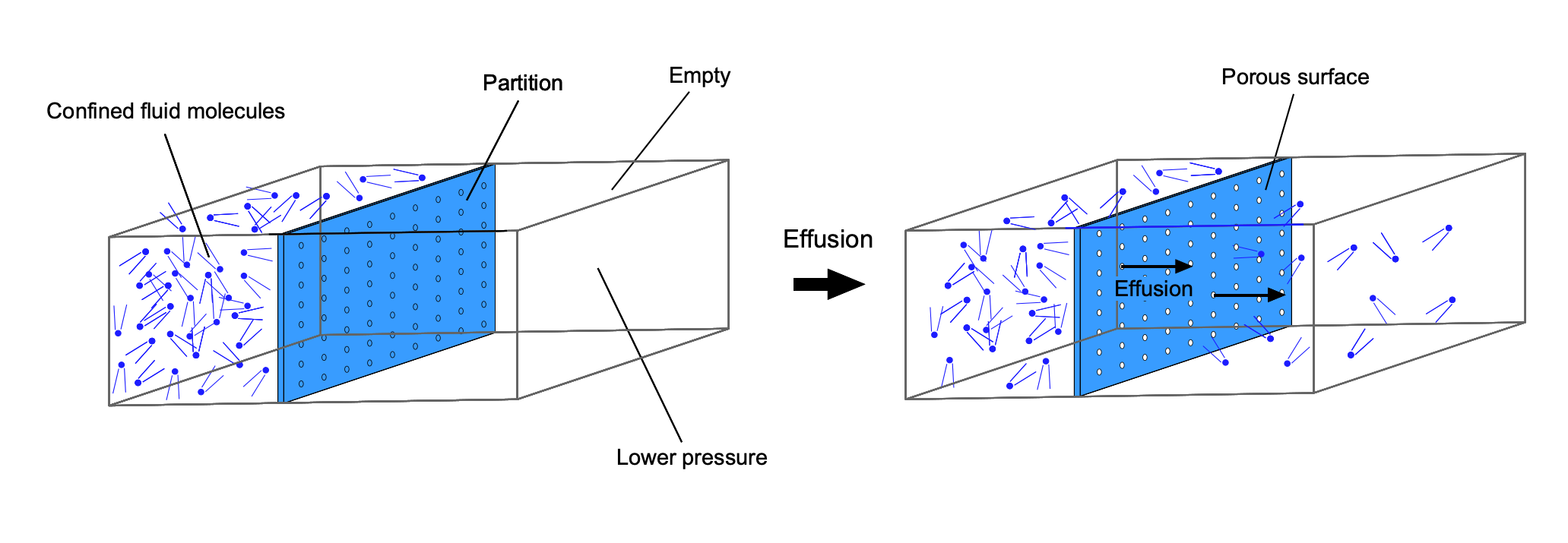

Diffusion & Effusion

One interesting characteristic of fluids is their rapid diffusion or mixing ability at the molecular level, even without turbulence or other agitation. Gaseous molecules travel at relatively high speeds, so they collide frequently with other molecules as they travel in many directions. Understanding and predicting the diffusion of gases and other fluids, as well as aerosols[11] or particulates suspended in fluids (colloids),[12] is fundamental to many engineering applications.

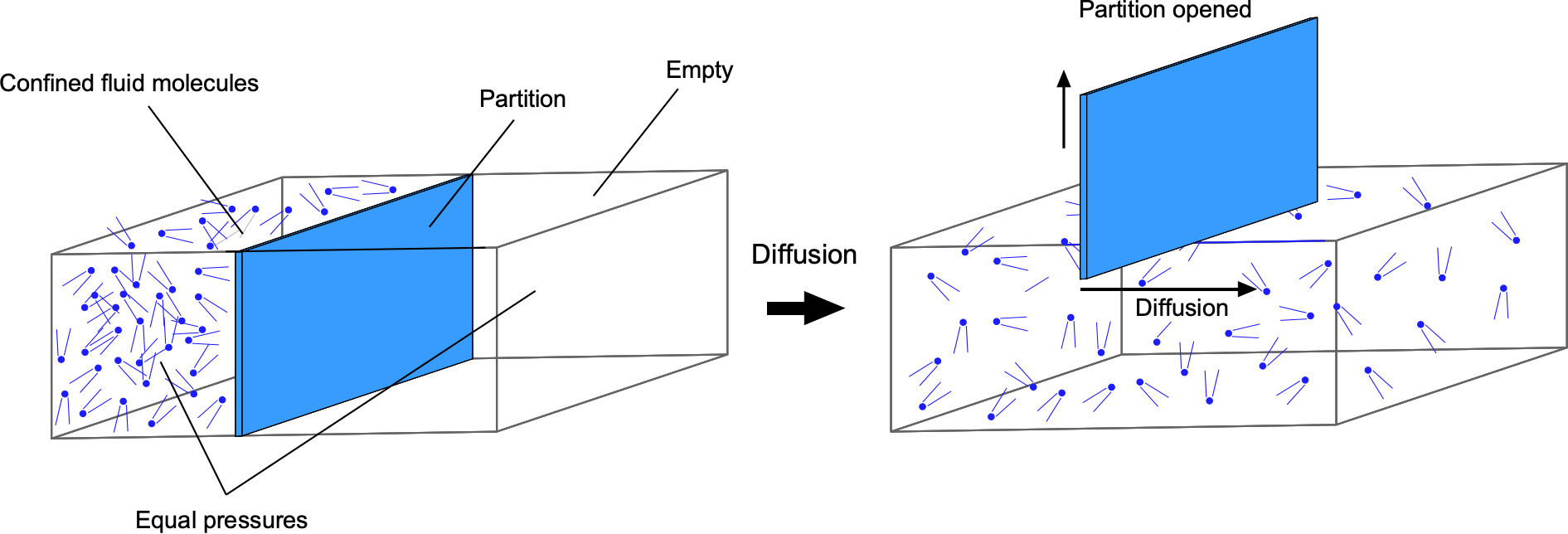

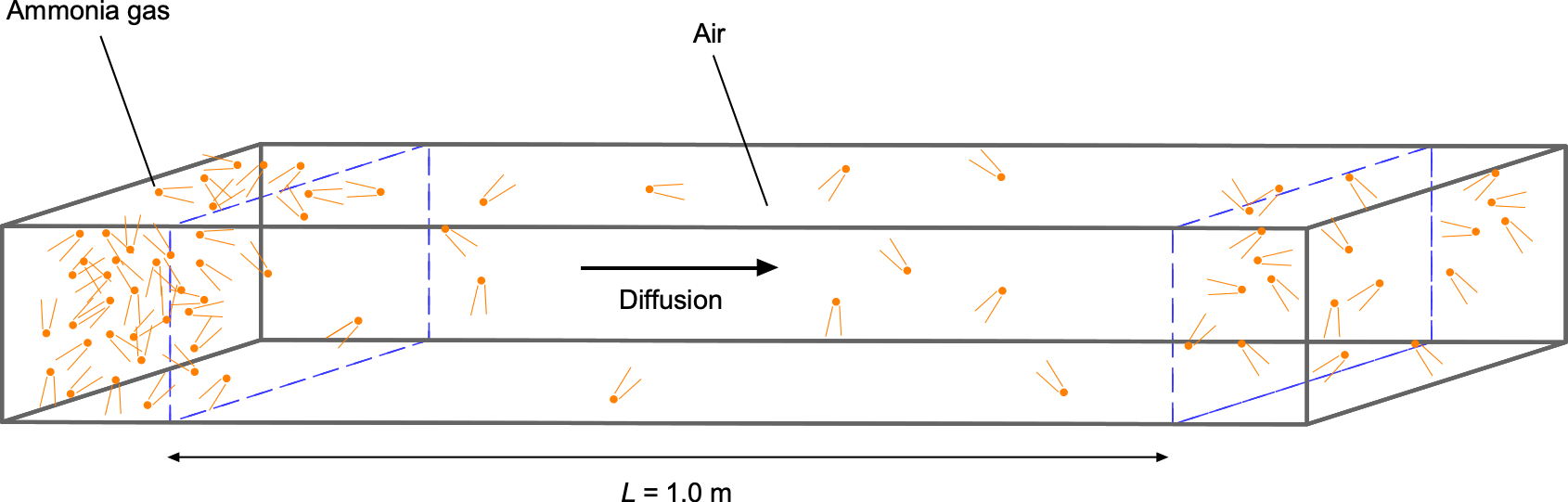

Diffusion

Diffusion is a process in which fluid molecules move through a concentration gradient from an area of higher concentration to a lower one until they are more evenly mixed, the idea being shown in the figure below. This movement is driven by the kinetic energy and natural mixing of the molecules and continues until a uniform equilibrium is reached. Diffusion is generally faster in gases because the molecules are further apart and move more freely, especially in gases with low molecular weight. Diffusion at the molecular level is relatively slow, but its rate is considerably enhanced by turbulence or other forced processes such as convection.

The diffusion characteristics of fluids can be predicted using Fick’s laws, after the work of Adolf Fick. In the case where the concentration gradient is time-invariant, the diffusion flux, J, which is the amount of substance per unit area per unit time, is proportional to the negative gradient of the concentration, C, i.e.,

(80)

where C is the concentration of the diffusing species, D is the diffusion coefficient, i.e., a measure of the diffusivity, and x is the spatial coordinate. Equation 80 is called Fick’s first law of diffusion. The negative sign in Eq. 80 indicates that the flux occurs in the direction of decreasing concentration. The diffusion coefficient, D, depends on the properties of the fluid, including its viscosity and temperature. Fick’s law is empirical in origin and was developed by following the work of Thomas Graham.

Fick’s first law of diffusion can also expressed in terms of densities, with the concentration, C, being replaced by the density . The density

represents the mass per unit volume instead of the number of particles per unit volume. This alternative form of Fick’s first law is given by

(81)

where J is the mass flux of a substance that flows through a unit area per unit time. In this form, Fick’s first law can be stated that the mass flux of a substance is proportional to the density gradient of that substance, with the direction of flux being opposite to the direction of the gradient. Fick’s law can also be expressed in terms of molecular mass, which is usually referred to as Graham’s law.

Note on units in Fick’s law

If the concentration, C, is measured in moles, as in Eq. 80, which is the classic form, the diffusive flux, J, representing the amount of substance that flows through a unit area per unit time, will have units of mol m s

. The diffusion coefficient or diffusivity, D, will be in units of m

s

. If the concentration is measured in terms of density, as in Eq. 82, which will be in units of kg m

, the diffusive flux, J, will be in units of kg m

s

, with the diffusivity, D, still in units of m

s

.

Fick’s second law applies to non-steady-state diffusion, where the concentration within the diffusion medium changes with time, which is expressed by

(82)

For practical problems involving the diffusion of gases, an important application of Fick’s second law is in estimating the diffusion time for spherical spreading. This is particularly useful in scenarios where a substance is diffusing from or to a spherical source, such as a gas bubble in a liquid or a spherical grain in a gas. The diffusion time, , can be approximated by

(83)