23 Applications of the Conservation Laws

Introduction

The practical application of the conservation equations in fluid dynamics is best learned by studying and understanding exemplar problems. Remember that exemplars of the field are “Key examples chosen so as to be typical of designated levels of quality of competence.”[1] Such exemplars in fluid dynamics include applications to flow through pipes and ducts, venturimeters used for flow measurement, Pitot tubes and Pitot-static systems for flow speed and airspeed measurement, understanding the essential performance and efficiency of propulsion systems such as jet engines, and the forces on airfoil sections and other bodies. After working through a few exemplars, the systematic solution process for applying the conservation equations will become apparent, allowing new and more ambitious problems to be tackled with greater confidence.

Generally speaking, all three conservation laws must be used to solve practical problems in fluid dynamics, i.e., using the governing equations to conserve mass, momentum, and energy. However, using all three equations is not always necessary. Conservation of mass is generally always required in problem-solving. Energy principles will inevitably be needed whenever pressure is involved as an unknown in the problem. The momentum equation will be necessary whenever forces are involved. An auxiliary equation, the equation of state, may also be necessary for problems involving compressibility effects. The Bernoulli equation can be used as an alternative to the formal energy equation, but only for steady, incompressible, inviscid flows that involve no work or energy addition. This restriction on its use should always be kept in mind.

Learning Objectives

- Calculate the flow properties through a Venturi and the contraction and test section of a wind tunnel using the fundamental conservation laws of aerodynamics.

- Understand the principles associated with the operation of a Pitot tube and how to measure static and dynamic pressure.

- Use the conservation laws in the integral form to find the drag on a body.

- Analyze the essential performance of a propulsive system such as a jet engine.

Flow in a Venturi

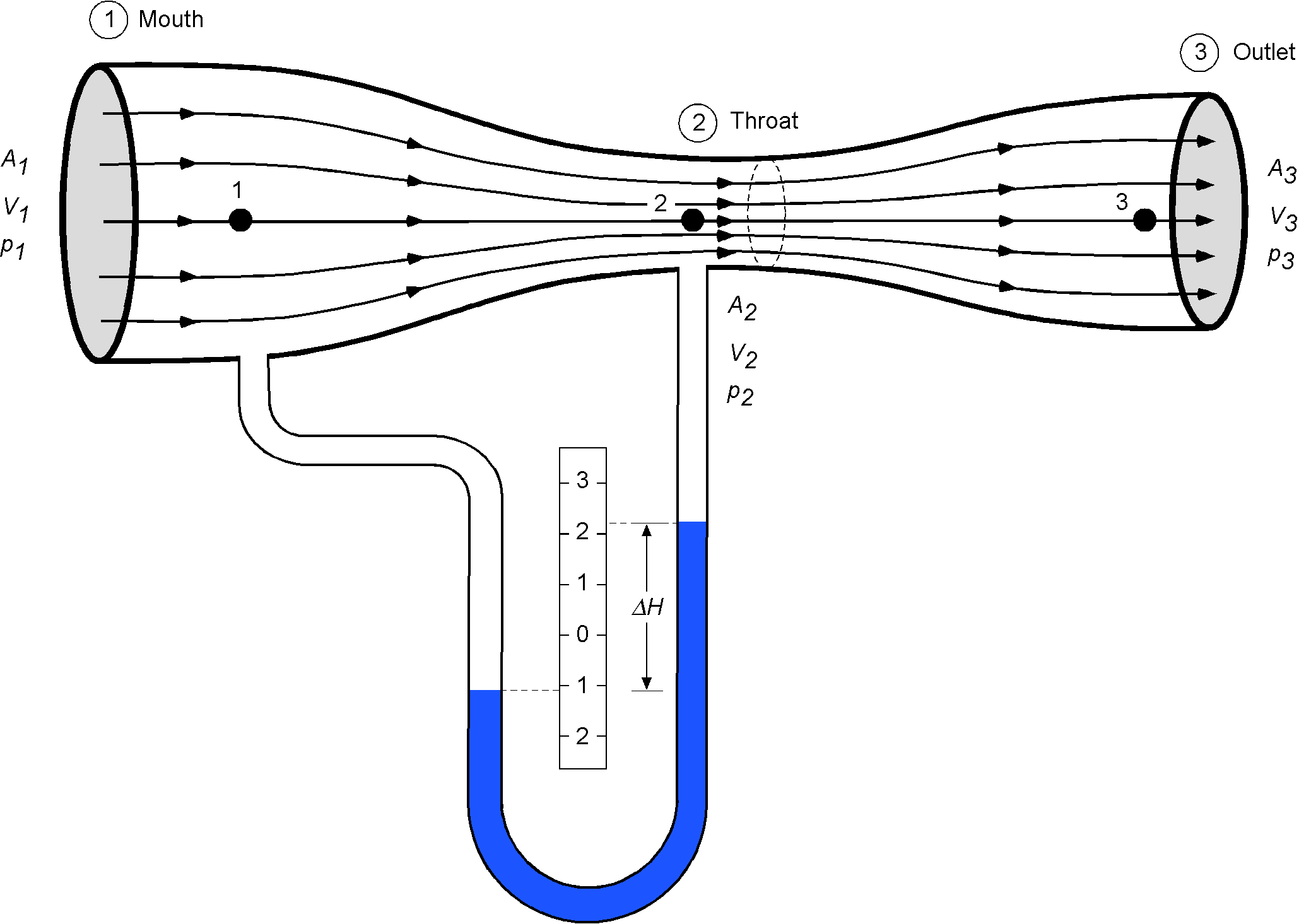

Consider the steady, incompressible flow (i.e., is a constant) through a convergent-divergent nozzle, as shown below, which is called a Venturi (with a capital V), after Giovanni Battista Venturi. If the flow is assumed to be incompressible, then the fluid can be either a liquid or a gas, such as air, but flowing at low velocities, i.e., all flow velocities must be below a Mach number of 0.3, which may not be known a priori.

The intake to a Venturi is referred to as the mouth, and the narrowest part is called the throat. Following Bernoulli’s principle, a pressure drop occurs at the throat of a Venturi where the flow speeds up. This behavior can be advantageous in several practical applications, such as flow meters, carburetors, and wind tunnels.

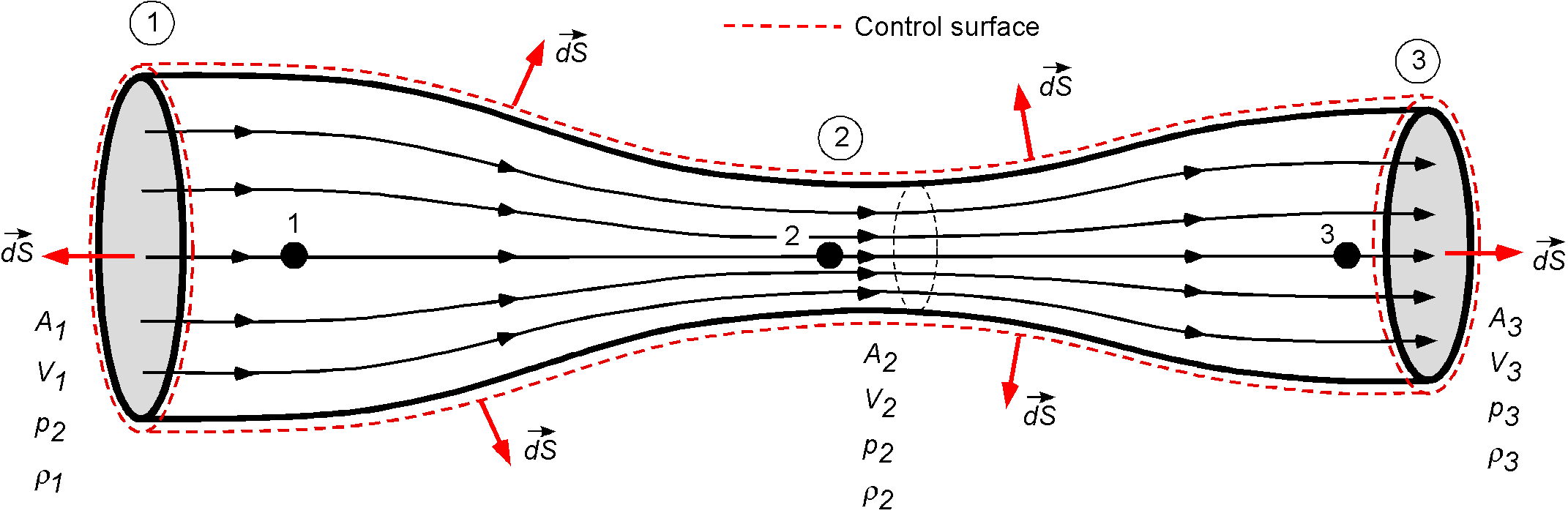

The first step in analyzing the flow through a Venturi is to draw a control surface around the venturi, with pointing out of the control volume by convention, as shown below. Let the inlet conditions be at section 1, the throat at section 2, and the outlet at section 3. The cross-sectional areas in each case are assumed to be known, such as by measurement. The flow can be considered steady and radially axisymmetric, i.e., an appropriate one-dimensional flow assumption.

The steady form of the continuity equation in integral form is

(1)

In words: “What mass flow comes into the control volume per unit of time then leaves the control volume in the same time, i.e., no fluid mass accumulates inside the control volume.”

There is no flow over the venturi’s walls, so the fluid mass flow that comes into the venturi’s mouth per unit of time also leaves simultaneously at its exit. A one-dimensional flow assumption can significantly simplify the problem if the variation in cross-sectional area is relatively moderate. However, further consideration is also needed as to why a flow through a rapidly converging or expanding Venturi (or duct) may not be as readily justifiable as a one-dimensional problem.

The flow enters the mouth of the Venturi of area with an average velocity

, has a velocity

at the throat of area

, and a velocity

at the exit of area

. The fluid mass flow coming in is

(2)

The minus sign appears because the flow is opposite to the direction of at the entrance face. At the exit face, then

(3)

Therefore, by using the continuity equation, then

(4)

which, for a one-dimensional flow, becomes

(5)

If the flow is incompressible, . Under these circumstances, the continuity equation can now be written as

(6)

or

(7)

Also, it will be apparent that

(8)

Canceling through the density gives

(9)

This equation states that the volume flow rate through the Venturi is constant.

It can also be seen from this latter equation that if the throat area decreases, then the flow velocity must increase there so that the continuity of the flow is satisfied, i.e., the mass and volume flow rates are constant at any one cross-section. Conversely, if the area of the throat increases, the flow velocity must decrease. Moreover, from the previous discussion of Bernoulli’s equation, remember that when the velocity increases, the pressure decreases; conversely, when the velocity decreases, the pressure increases, i.e.,

(10)

or

(11)

(12)

The pressure difference can be measured across the mouth and throat of the venturi, which can be accomplished by drilling two small holes[2] (i.e., pressure taps) perpendicular to the Venturi walls at locations 1 and 2. The pressures are then measured by connecting tubes from these holes to a differential pressure gauge or the two sides (legs) of a U-tube manometer; see here for a simple experimental demonstration of this process. This pressure difference can then be related to the unknown velocity (or flow rate) through calculation or direct calibration using measurements.

From the continuity equation, then

(13)

and from Bernoulli’s equation

(14)

Substituting gives

(15)

and so

(16)

Therefore, knowing the pressure difference and the geometry of the Venturi (the area ratio), the flow rate

can be determined. Finally, notice that the change in pressure can be related to a change in the hydrostatic head of the fluid

, using

(17)

where is the density of the liquid in the U-tube manometer.

Applications of a Venturi

A Venturi has many applications in practical engineering. Its primary characteristic is that the flow velocity is higher in the venturi’s throat. As a result, the pressure at the throat is lower than the atmospheric pressure, and this pressure difference is helpful for various purposes.

Flowmeter (Venturimeter)

As the previous analysis suggests, a Venturi forms the basis for a device used to measure volume (or mass) flow rates. Such flowmeters, or venturimeters as they are often called, are commercially available in various sizes and capacities. They are widely used in the water, chemical, pharmaceutical, and oil and gas industries to measure fluid flow rates along ducts and pipes, an example being shown in the figure below. While venturimeters operate fundamentally on Bernoulli’s principle, which states that pressure decreases in the throat of the venturi, they are usually calibrated at the factory to account for any losses, allowing volumetric flow rates to be more accurately related to the measured pressure drop across the throat. Four pressure taps are typically located at each section, which are pneumatically averaged together to provide a more consistent and accurate reading of the static pressure drop between the entrance and the throat.

The volumetric flow rate can be obtained from the ideal fluid assumption derived previously with a correction factor to account for any viscous losses, i.e.,

(18)

where is a calibration factor. The value of

is usually close to 1, but it will depend on the specific venturi.

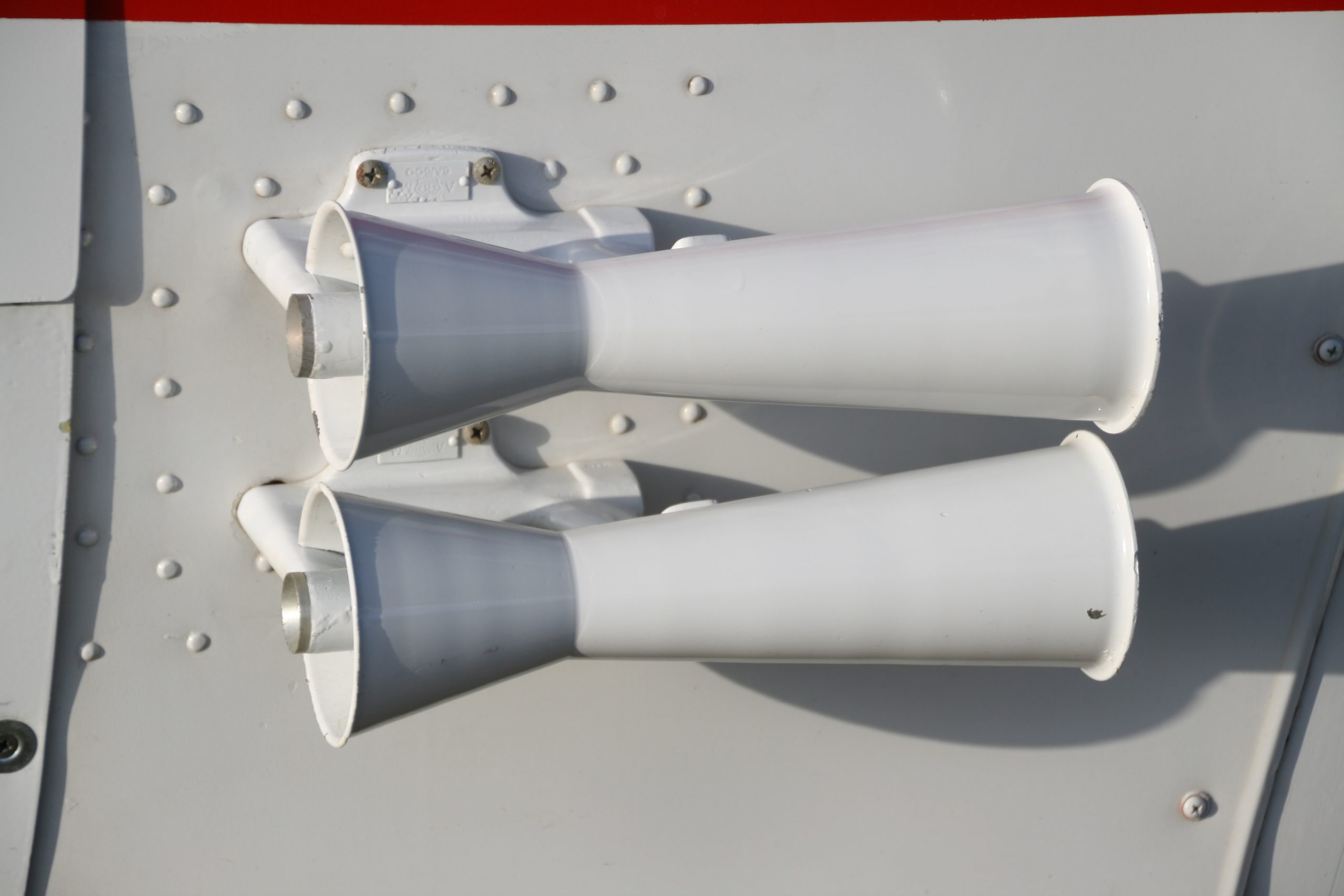

Suction Source for Flight Instruments

In early aircraft, a Venturi (or sometimes a pair of Venturi tubes) was mounted on the side of an aircraft’s fuselage, as shown in the photograph below. The Venturi provided low suction pressure for air-driven gyroscopic instruments, such as the artificial horizon and directional gyro. Modern light aircraft, however, are fitted with mechanical engine-driven vacuum pumps to provide the needed suction pressure, so venturis are no longer required.

From the continuity equation, the velocity at the throat, , for a given airspeed,

, is

(19)

where is the inlet area, and

is the area of the throat. From the Bernoulli equation, then

(20)

Therefore, the suction pressure available at the throat relative to static pressure is

(21)

which shows that it decreases with the square of the airspeed at a given density altitude.

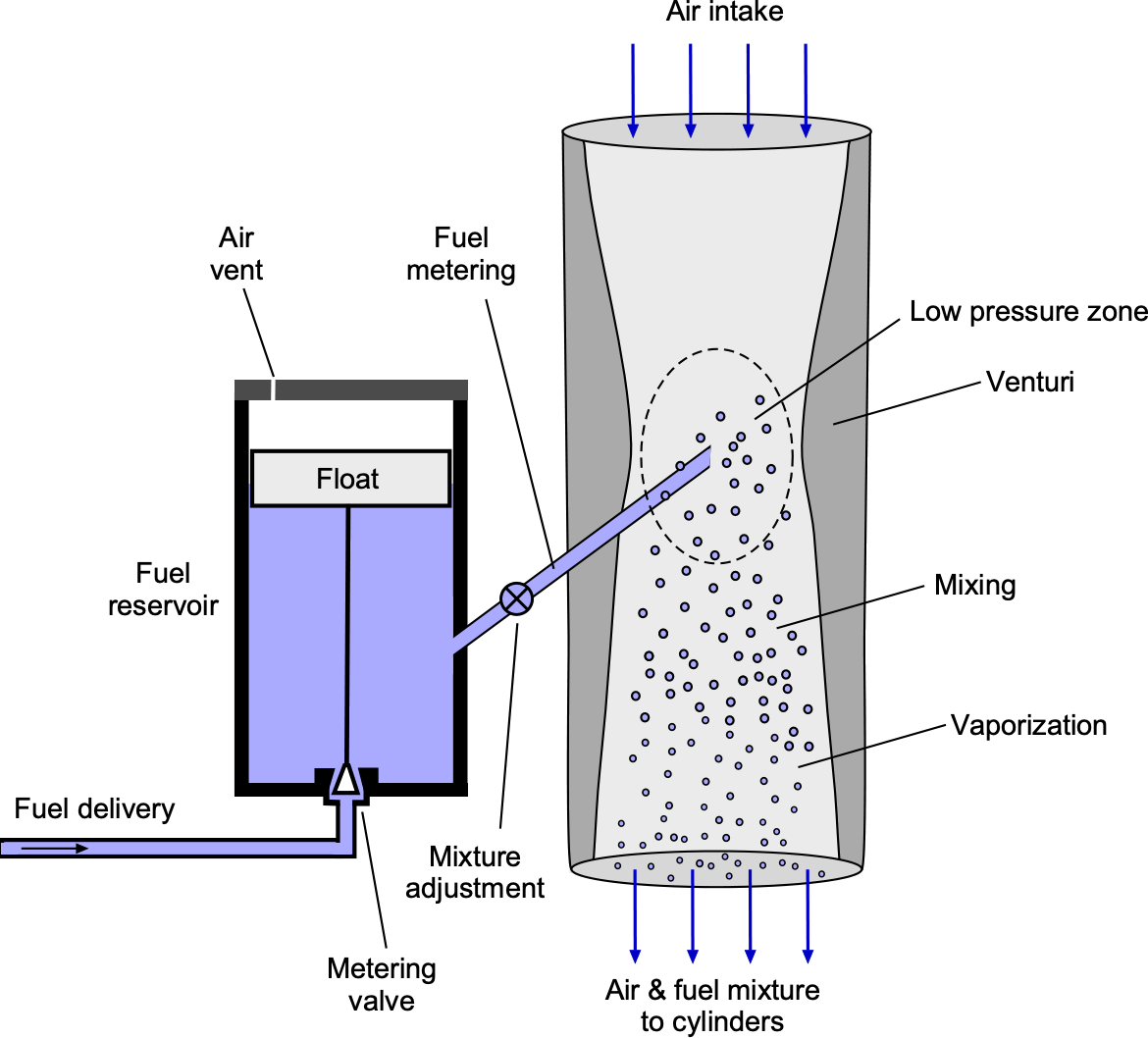

Carburetor

A carburetor provides an air-fuel mixture to a piston (reciprocating) engine. A carburetor has a Venturi through which incoming air is mixed with fuel. Fuel from a tank is sent to a fuel reservoir, where the fuel level is maintained using a float. The fuel delivery line opens into the Venturi in the carburetor’s throat, where the fuel is first atomized. The lower pressure in this region helps draw fuel into the airstream, mix it with the air, and vaporize it downstream of the throat before the resulting fuel-air mixture enters the cylinders to be burned. Metering the fuel requires fine adjustment to ensure that the correct air-fuel mixture is delivered to each cylinder, which maximizes power from the engine and minimizes hydrocarbon emissions.

Flow Speed in a Wind Tunnel

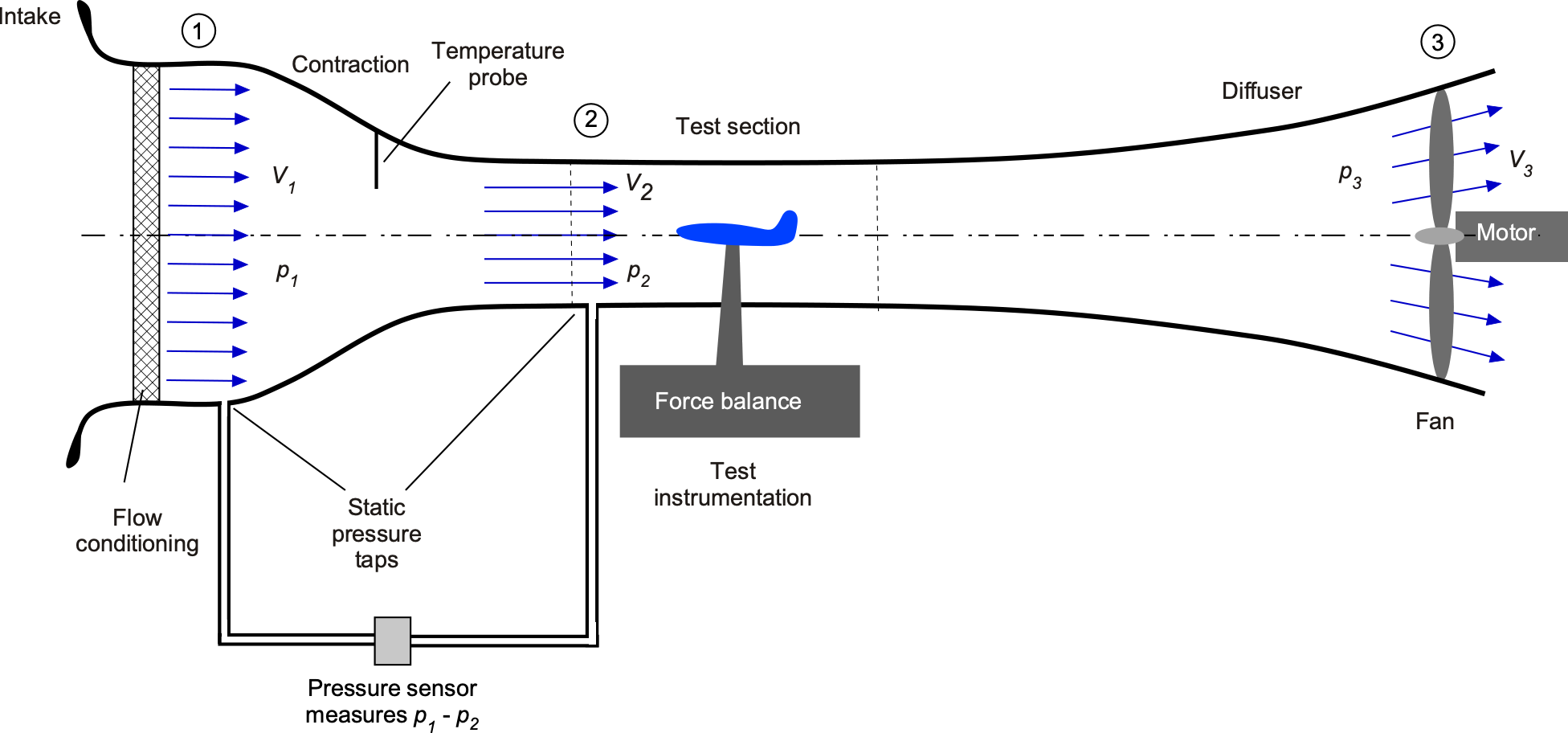

A low-speed wind tunnel is a large Venturi in which the airflow is driven by a fan connected to a motor drive. The wind tunnel fan is a large propeller specifically designed to move the air efficiently through the test section, as shown in the figure below. This is an open-return or Eiffel-type wind tunnel, while the other type is a closed-return or loop type.

The airflow enters the mouth of area at a flow velocity

with pressure

. The wind tunnel then contracts to a smaller area,

, at the test section, where the velocity has increased to

. The velocity in the test section must increase if continuity is satisfied. The model (such as a wing or a complete airplane model) is placed in the test section, where its aerodynamic characteristics are measured and recorded. The flow then passes downstream into a diverging duct called a diffuser, where just before the fan, the area is

, the velocity reduces to

, and the pressure increases to

.

From the continuity equation, the air velocity in the test section is

(22)

In turn, the velocity at the exit of the diffuser before the fan is

(23)

The pressure at various locations in the wind tunnel is related to the velocity by Bernoulli’s equation

(24)

The velocity in the working or test section (the most important quantity) can be related to the pressure drop across sections 1 and 2, i.e., the pressure drop between the mouth of the contraction section and the test section. From the Bernoulli equation, then

(25)

This means that

(26)

Solving for (the flow velocity in the test section) gives

(27)

The area ratio is fixed for a given wind tunnel. Recall that the density is a constant for an incompressible flow. Its value can be obtained from measurements of static pressure and temperature in conjunction with the equation of state.

Therefore, the above equation can be used to determine the velocity in the test section by measuring the pressure drop from the intake to the contraction and the test section. This latter technique is used in most low-speed wind tunnels to measure the flow speed in the test section, i.e., the drop in pressure between some point on the contraction and the test section is measured. This pressure drop is then related to the flow velocity in the test section using Bernoulli’s equation and confirmed by calibration. In the calibration, a Pitot probe (see discussion below) is placed in the test section, and the pressure drop is measured for a range of flow speeds; any discrepancy leads to a calibration factor, , that can be used to determine the flow speed more accurately, i.e., using

(28)

In practice, the calibration factor for a low-speed wind tunnel is close to 1.

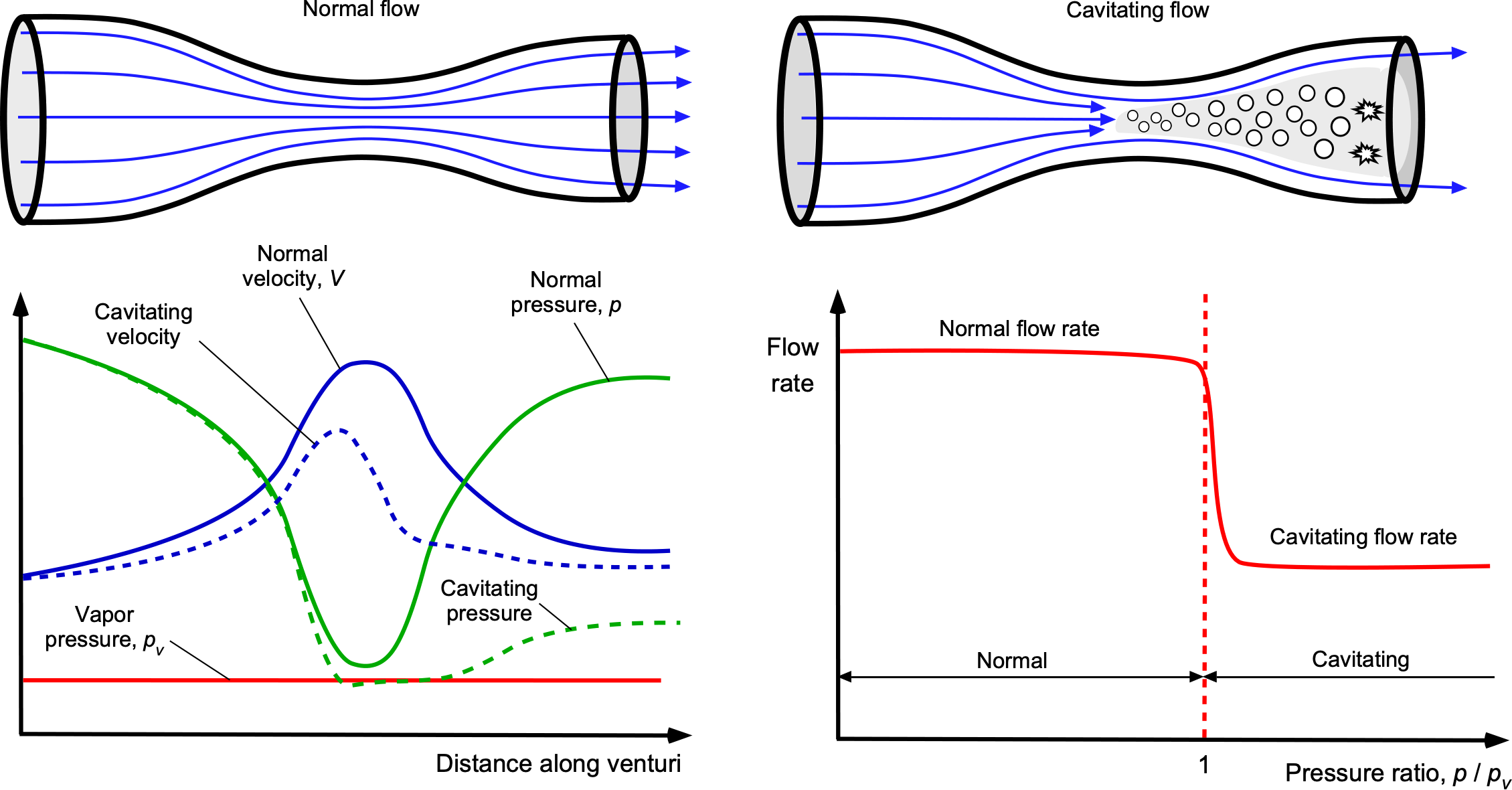

Cavitating Venturi

Cavitating venturis can be used to control or limit the flow rate of a liquid through a pipe. The throat of a cavitating Venturi is sized such that for a given differential pressure drop between the inlet and the throat, the pressure at the throat is reduced to its vapor pressure point, , as illustrated in the figure below. The resulting vapor and bubbles that form, known as cavitation, are similar to boiling without the addition of heat. This phenomenon will then limit the mass flow rate through the venturi, preventing any additional increase in flow rate for a given upstream inlet pressure. As the bubbles travel downstream into the throat, they eventually burst, and the static pressure recovers to the pre-cavitation values. The mass flow rate through the pipe is not dependent on the downstream pressure; therefore, the mass flow can be controlled by changing the inlet pressure, and hence, the amount of cavitation in the throat. Cavitating venturimeters are often used as propellant mass flow limiters in rocket engines.

The cavitation number is usually expressed as

(29)

where is the flow velocity at the throat. This is a form of pressure coefficient, so cavitation will first occur at

. The volumetric flow rate through a Venturi is given by

(30)

where is the entrance pressure to the venturi, and

is the pressure in the throat. The entrance area is

, and the throat area is

, both of which can be measured. If the pressure in the throat equals the vapor pressure, i.e.,

and

, then the flow rate will become cavitation-limited to a maximum value of

(31)

After reaching this point, further attempts to increase the upstream pressure will be ineffective in increasing the flow rate. Vapor pressures, , for different liquids at different temperatures can be found in various online resources and in the table below. Knowing the vapor pressure also allows the Venturi to be designed to limit volumetric or mass flow rate. For example, for given values of

,

, and

, the throat area

can be determined to limit the flow rate from the onset of cavitation.

| Liquid | Vapor pressure (Pa) | Vapor pressure (lb/ft2) |

|---|---|---|

| Water | 3,166.6 | 0.0666 |

| JET-A | ~ 2,000 | ~ 0.04206 |

| 100LL gasoline | ~ 40,000 | ~ 0.8413 |

| Ethanol | 5,853.7 | 0.1227 |

| Acetone | 24,266.4 | 0.5085 |

| Diethyl ether | 53,465.3 | 1.1195 |

| Methanol | 16,931.5 | 0.356316 |

| Hexane | 19,995 | 0.4201 |

| Chloroform | 26,384.9 | 0.5543 |

| Carbon tetrachloride | 12,125.7 | 0.2555 |

| Benzine | 12,661.2 | 0.2673 |

Siphon (Syphon)

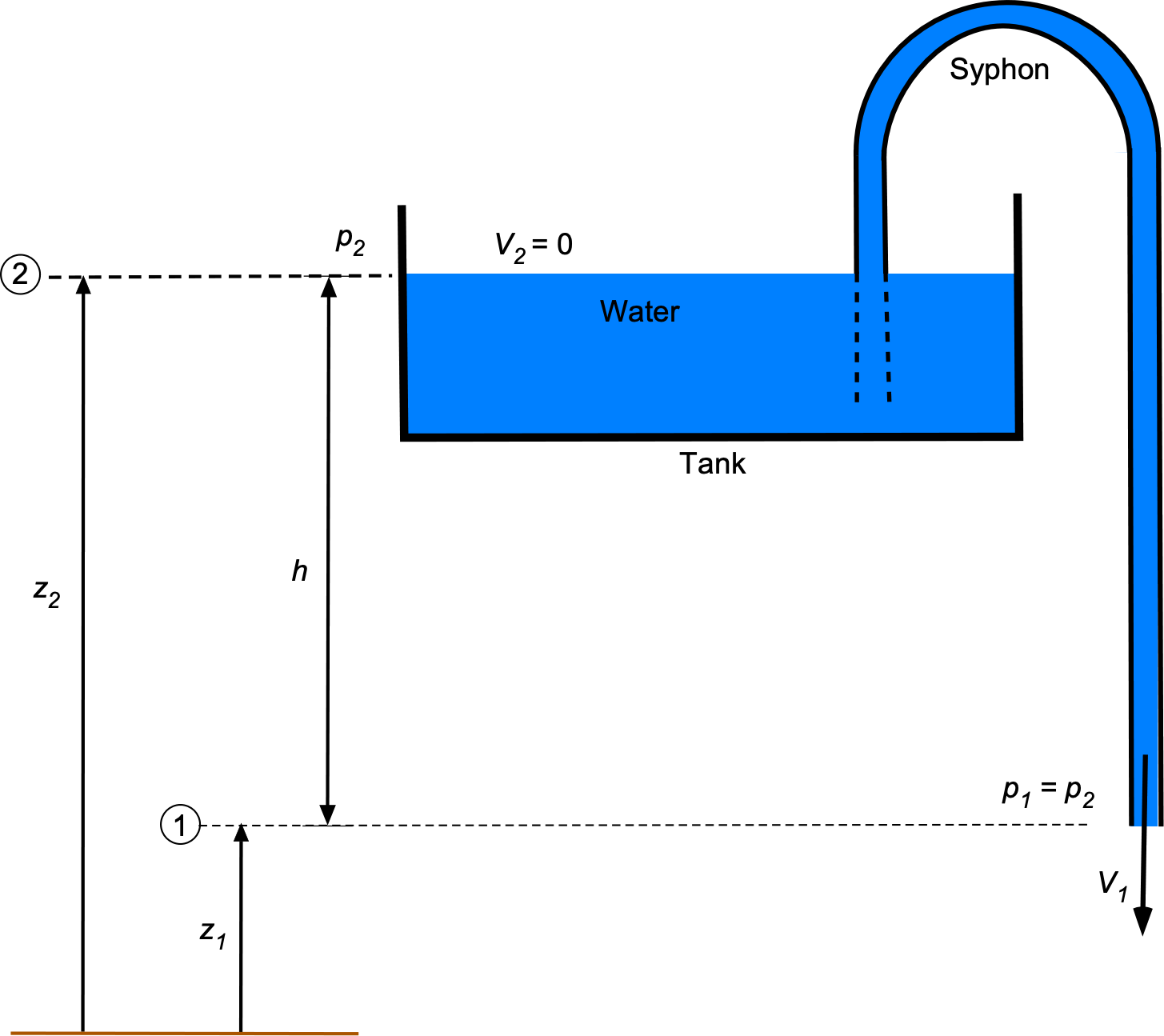

A siphon, also spelled syphon, is a device used to transfer liquids from one level to another. It consists of a tube or hose bent in a U-shape, with one end placed in some liquid, such as water, and the other set at a lower level, as shown in the figure below. This arrangement allows the water to flow from the tank to a lower level, which relies on the principle of gravity and hydrostatic pressure. To start the flow, the siphon tube must be filled with water, which can be done by suctioning the air out of the tube or by filling it with water and submerging one end in the tank. Once the flow starts, it will continue until the tank is emptied.

It is often claimed that a siphon works on the principle of air pressure, but this is incorrect. To see why, the Bernoulli equation applied in the fluid between the tank and the outlet from the siphon gives

(32)

The change in air pressure between the levels at and

is minimal, so it can be assumed that

. Also, if the fluid in the tank is assumed to be of much greater volume than the volume flow rate out of the siphon, then

= constant. Therefore, under these quasi-steady assumptions, the Bernoulli equation becomes

(33)

or

(34)

Rearranging gives the outlet flow velocity as

(35)

which is called Torricelli’s law.[3] Notice that the flow velocity depends on the difference in the height of the water, , and acceleration under gravity, so the higher the height difference, the faster the water will flow. There is no significant change in atmospheric pressure between the two levels. Therefore, the siphon effect is produced by the hydrostatic pressure difference within the liquid, not the (slight) difference in atmospheric air pressure.

However, considering viscous effects (and hence losses) will change this result because there will be some small pressure drop along the length of the siphon tube. Calculating such internal pressure losses and flow velocity requires a viscous flow theory, which will be considered in a later chapter of this e-book.

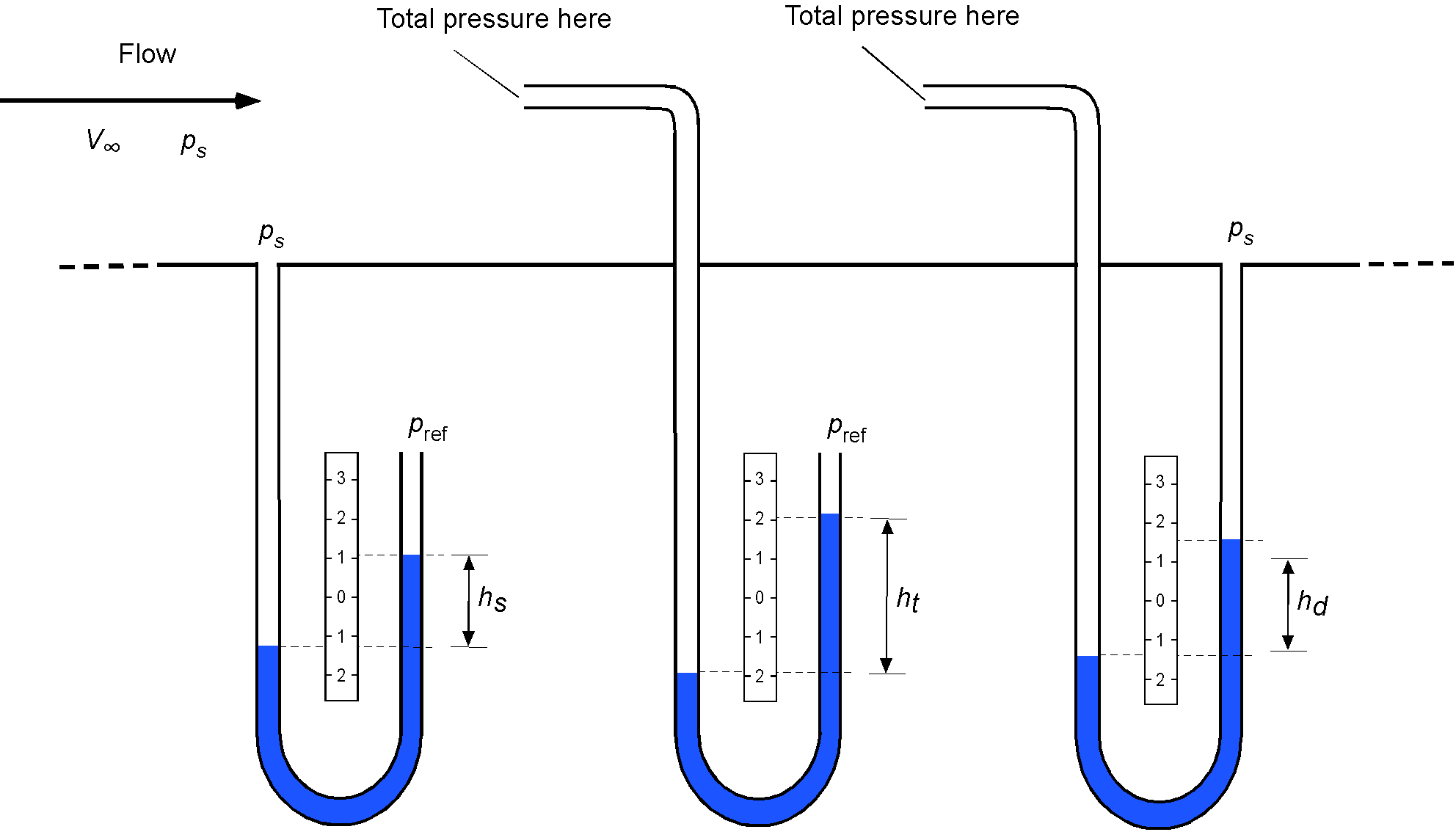

Total, Static, & Dynamic Pressures

It must now be explained more precisely what a fluid’s total and static pressures mean. Consider a flow moving with velocity at a pressure

. If moving with the velocity of the airflow, then the pressure that will be felt is

. This latter pressure is called static pressure and measures the effects produced by the random motion of the fluid molecules. Now, if the boundary or “wall” of a flow is considered (e.g., the wall of a duct, pipe, or wind tunnel), and a small hole in the wall is drilled in perpendicular to the flow, then the pressure that is measured there would be the static pressure

.

Suppose a U-tube manometer is connected, as shown in the figure below, and the open end outside the flow (i.e., the reference end) of the manometer is at lower static pressure than in the flow. In that case, a difference in height will be shown on the manometer. The pressure is the static pressure between the flow and the ambient reference pressure, called the gauge pressure. If the static pressures inside and outside are equal, then

.

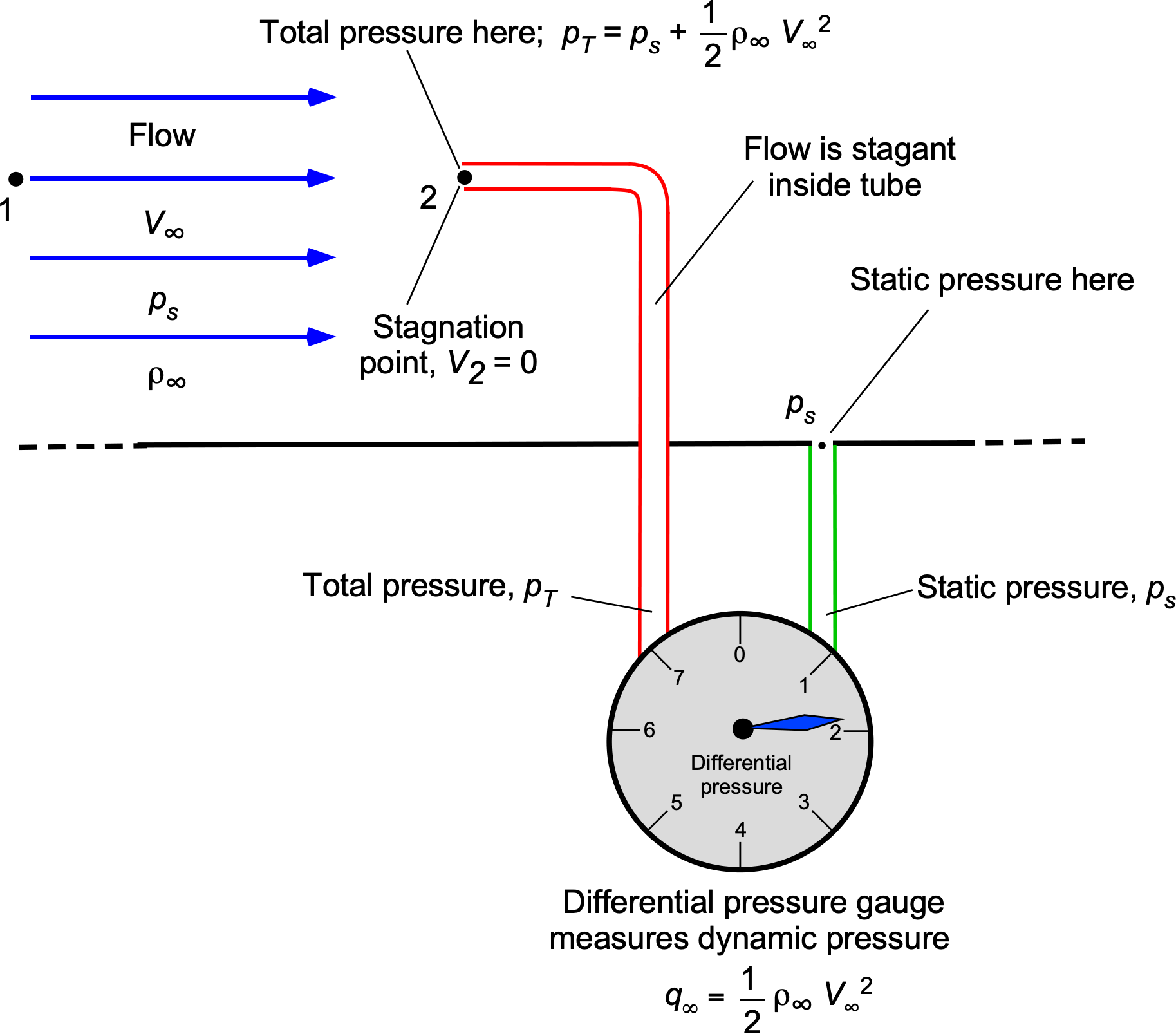

Now consider a Pitot tube (after the hydraulic engineer, Henri Pitot) inserted into the flow, which is an open tube with its end facing into the flow. The fluid cannot flow through the tube so it will stagnate in the tube, i.e., the flow velocity will go to zero at the entrance to the tube because there is no place for the fluid to flow. Hence, the streamline that infringes directly on the mouth of the Pitot tube will have zero velocity; this location is called a stagnation point. In this case, the pressure that is measured is called the total pressure, , which is the sum of the dynamic pressure and the static pressure, i.e.,

(36)

where is the density of the flowing fluid, with an equivalent height of the hydrostatic head on the manometer of

.

Finally, consider the case where the reference pressure is now the static pressure in the flow. In this case, the pressure would be the dynamic pressure of the flow, i.e., the difference between the total pressure and the static pressure

(37)

with an equivalent hydrostatic head of on the manometer.

Pitot Tube & Pitot-Static Tube

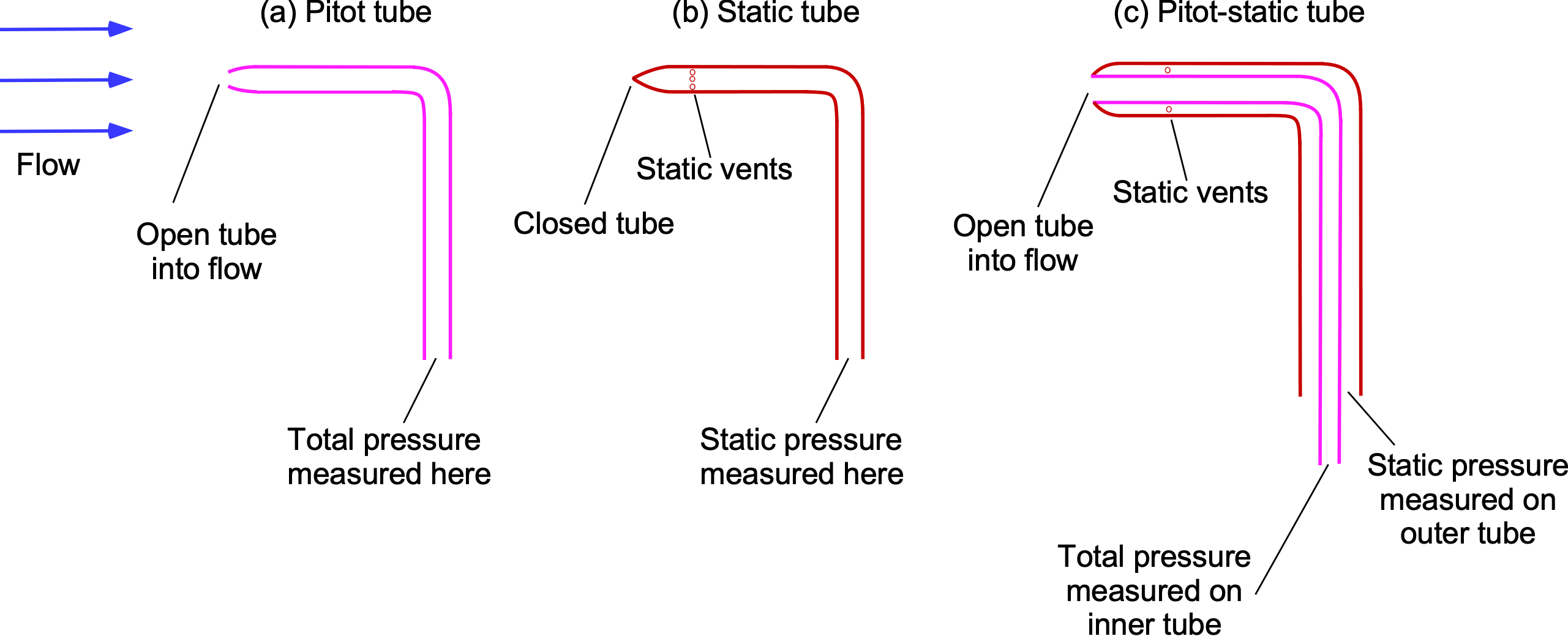

Pitot probes (or Pitot tubes), static probes, and Pitot-static probes are often used to measure flow velocities. In each case, the principle is the same: pressure measurements can be used with the Bernoulli equation to calculate the flow velocity. The proviso is that the density of the flow where the probe is inserted is known. These three types of pressure probes are shown in the figure below.

For the analysis of a Pitot tube, consider point 1 upstream of the Pitot tube and point 2 at the entrance to the tube, as shown in the figure below. From Bernoulli’s equation it is known that constant along any given streamline, so that

(38)

But at point 2 at the entrance to the Pitot tube, the fluid is brought to rest so (i.e., it is a stagnation point), and so

(39)

The static pressure must be measured to obtain the flow velocity from this latter expression. Like the Venturi problem, this static pressure can be measured with a separate static vent or with static ports on the outer side of a concentric Pitot-static tube. Solving for

gives

(40)

Therefore, the upstream flow velocity can be measured by measuring the difference between a flow’s total and static pressure. Again, this pressure difference can be measured using a differential gauge, manometer, or pressure transducer.

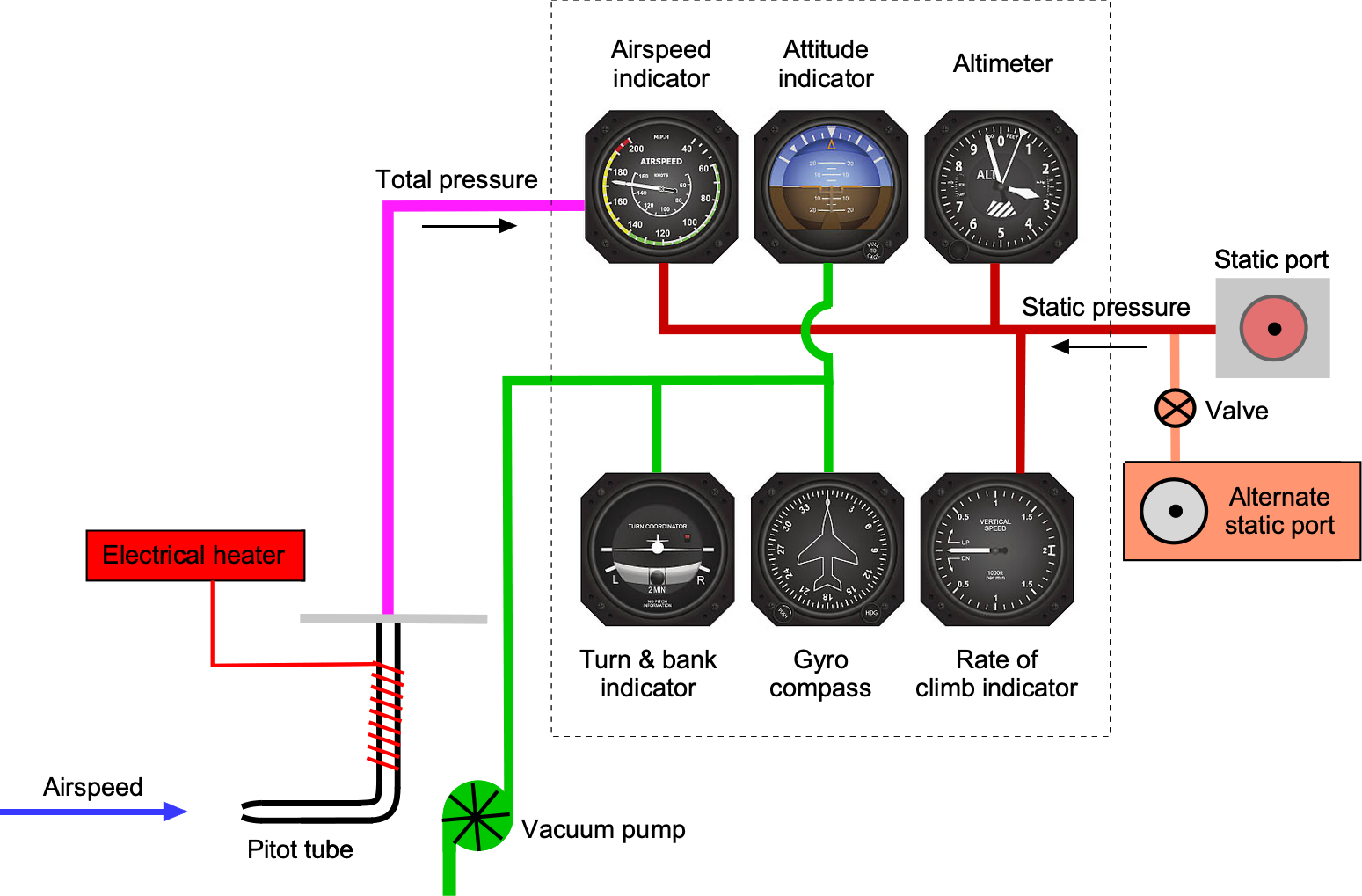

The preceding principles are used in airspeed measurement using an Air Speed Indicator (ASI), which is part of the pneumatic system used on an aircraft for not only airspeed measurement but also altitude and rate of climb, as shown in the figure below. An airspeed indicator is a suitably calibrated differential pressure gauge. The dynamic pressure source needed for an airspeed indicator is either a Pitot tube or a Pitot-static tube. Notice, in this case, the use of a Pitot probe to measure the total pressure probe and a separate static vent (usually placed somewhere on the side of the fuselage) to measure the reference pressure. A heater prevents the Pitot probe from malfunctioning in icing conditions by preventing ice accumulation on the exposed probe.

More often than not, airplanes use Pitot tubes (to measure total pressure ) with static taps (to measure

) placed at some other point on the airframe, as previously shown. In this case, then the airspeed

will be

(41)

In either case, the purpose is the same: to obtain a measurement of the aircraft’s airspeed. This information is then provided to the pilot on an airspeed indicator. Therefore, an airspeed indicator is just a dynamic pressure gauge calibrated in units of speed; usually, units of nautical miles per hour (kts) are used, but sometimes miles per hour (mph). An online simulator of the Pitot-static system helps understand how it works and what happens under various failure scenarios.

Flow Speed in a Wind Tunnel (Take 2)

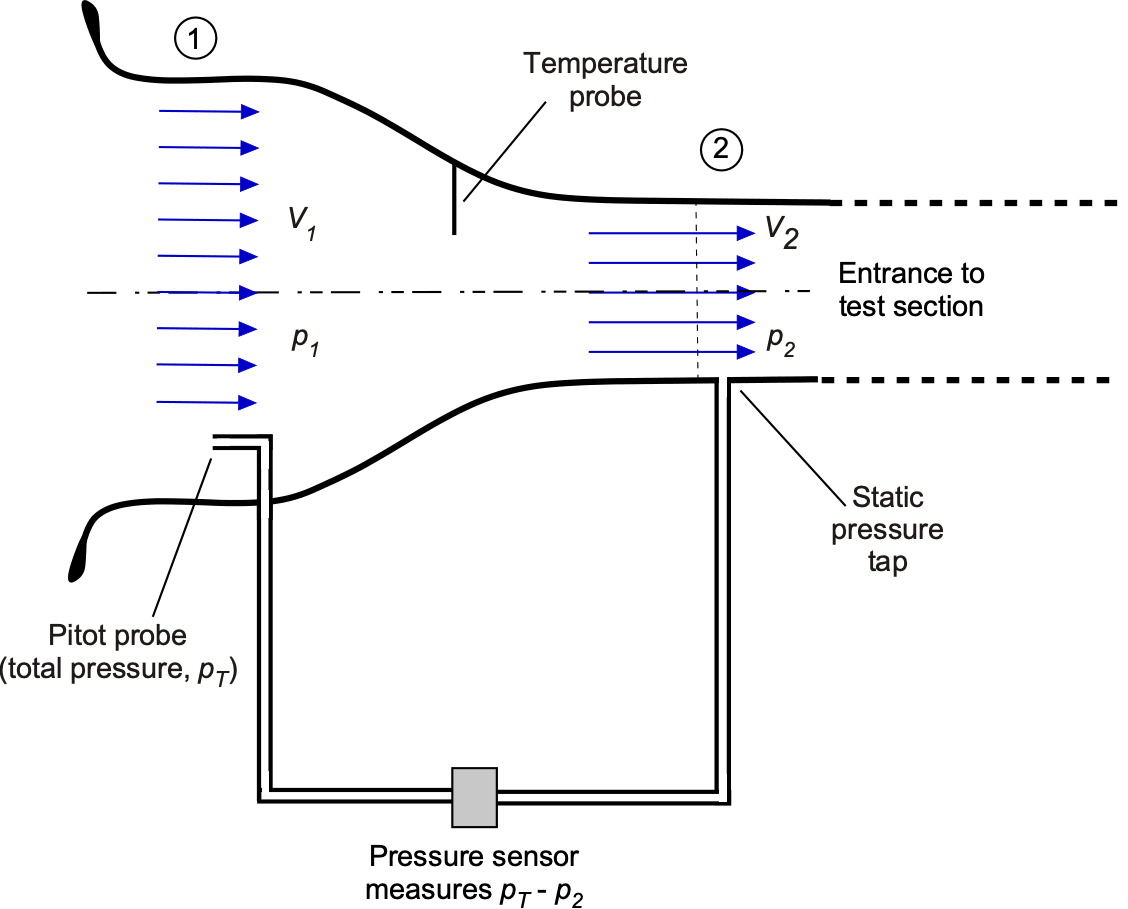

While it has been previously described how the flow speed in the test section of a wind tunnel can be obtained by measuring the static pressure drop between the inlet and the test section, another way is to use a Pitot probe, as shown in the figure below. The Pitot probe measures the total pressure, , in the upstream section or any upstream section that is convenient to do so. This approach tends to give a more accurate way of measuring dynamic pressure because it is the difference between a higher and a lower pressure rather than two lower pressures of similar magnitude.

From the Bernoulli equation, then

(42)

so that

(43)

Again, the value of density, , can be obtained from static pressure and temperature measurements in conjunction with the equation of state. The calibration would be verified by placing a Pitot probe in the test section to obtain any calibration factor,

, i.e.,

(44)

where will be very close to unity.

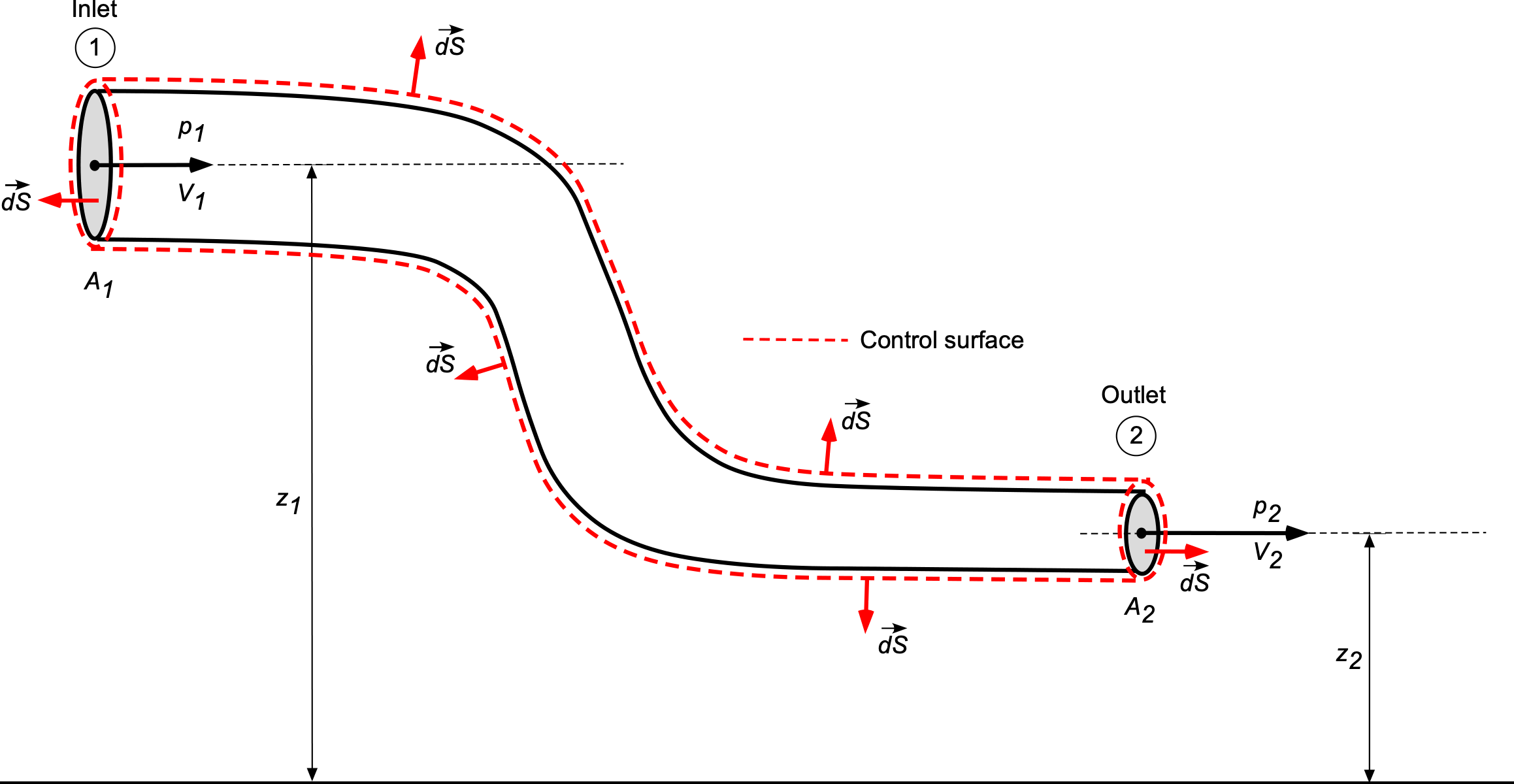

Force on a Pipe Bend

The determination of flow rates, flow velocities, pressures, and forces on fluids flowing through pipes and channels is a common application of the consdervation laws in integral form. Consider a flow through a pipe of circular cross-section and encounters a change in the area and height of the pipe as it passes through an elbow-type of coupling, as shown in the figure below. The pipe is in a vertical plane, e.g., the –

plane. Assume uniform flow properties across any cross-section and no losses, and that the fluid is water of density

.

The flow rate, , or the mass flow rate

are usually given, as well as the input and output areas, so tyat conservation of mass gives

(45)

Therefore, the flow velocities are given by

(46)

Using the Bernoulli equation gives

(47)

If, for example, is a known value, then rearranging to solve for

gives

(48)

The force on the pipe can be obtained from an assessment of the net pressure forces and the time rate of change of momentum. It will be apparent that the pressure force and momentum change only in the direction. The one-dimensional form of the momentum equation becomes

(49)

where is the force on the fluid, so that

(50)

Therefore, the reaction force on the pipe is then .

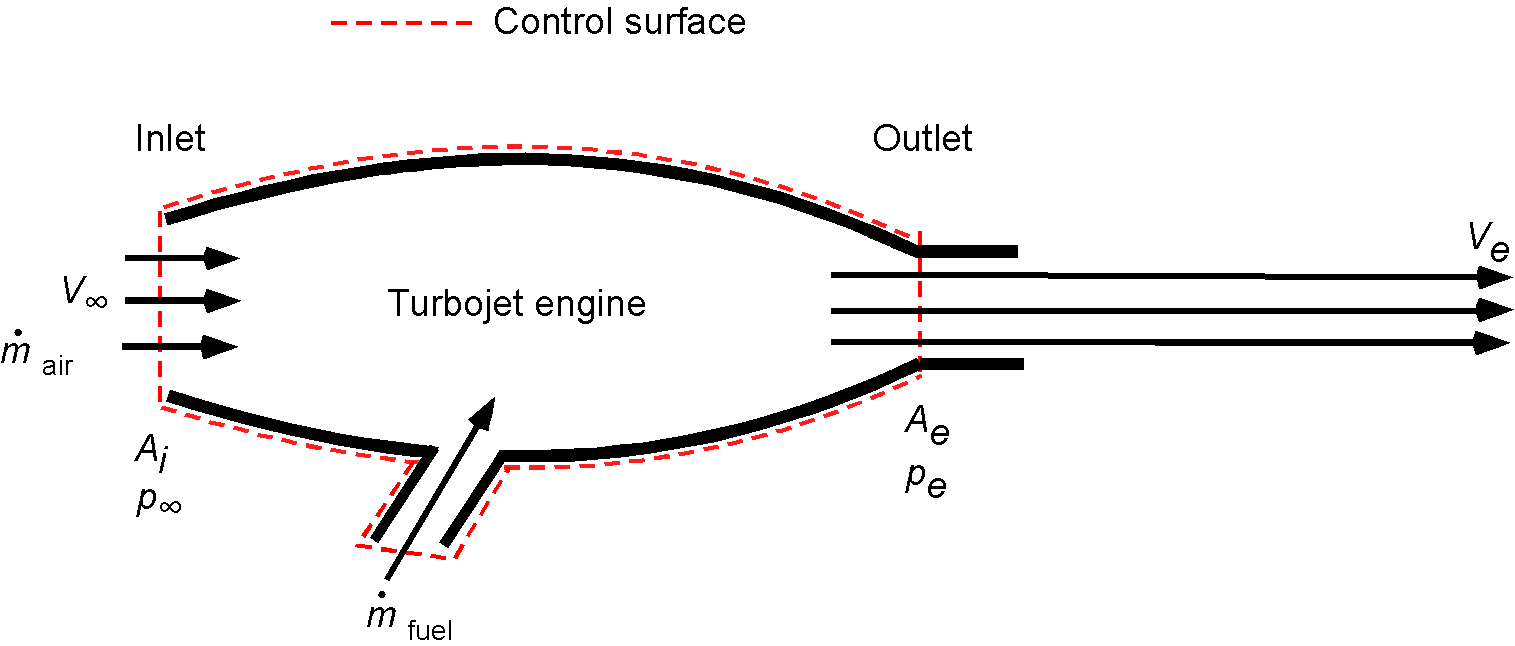

Jet Engine Performance

The thrust of a turbojet engine can be determined using conservation principles applied to a control volume surrounding the engine. There is a mass flow into the engine from the air and an additional mass flow from the fuel. Fuel is much denser than air, so although the volume flow of fuel may be relatively low, its mass flow is still significant and needs to be accounted for.

The mass flow of air into the engine will be

(51)

where is the inlet area, and the mass flow rate of fuel is

. Therefore, the thrust is

(52)

with as the exit area and

as the exit or “jet” velocity. The pressure term in Eq. 52 is relatively small compared to the change in momentum of the flow and so may be neglected, i.e.,

(53)

If the mass flow of the fuel (small) is neglected in comparison to the mass flow rate of air (high), then

(54)

Using the principle of conservation of energy, the propulsive efficiency can be defined as

(55)

which shows that losses appear as a gain in kinetic energy in the downstream jet flow. Substituting for the thrust gives

(56)

where to be meaningful . Notice that a low value of

for a given thrust and, hence, higher propulsive efficiency can be achieved by having a significantly high mass flow rate,

, through the engine. Therefore, even with this relatively simple analysis, it can be concluded that it is more efficient to create thrust by accelerating a large air volume (mass flow rate) at a lower

versus a lower air volume (mass flow rate) at a high

.

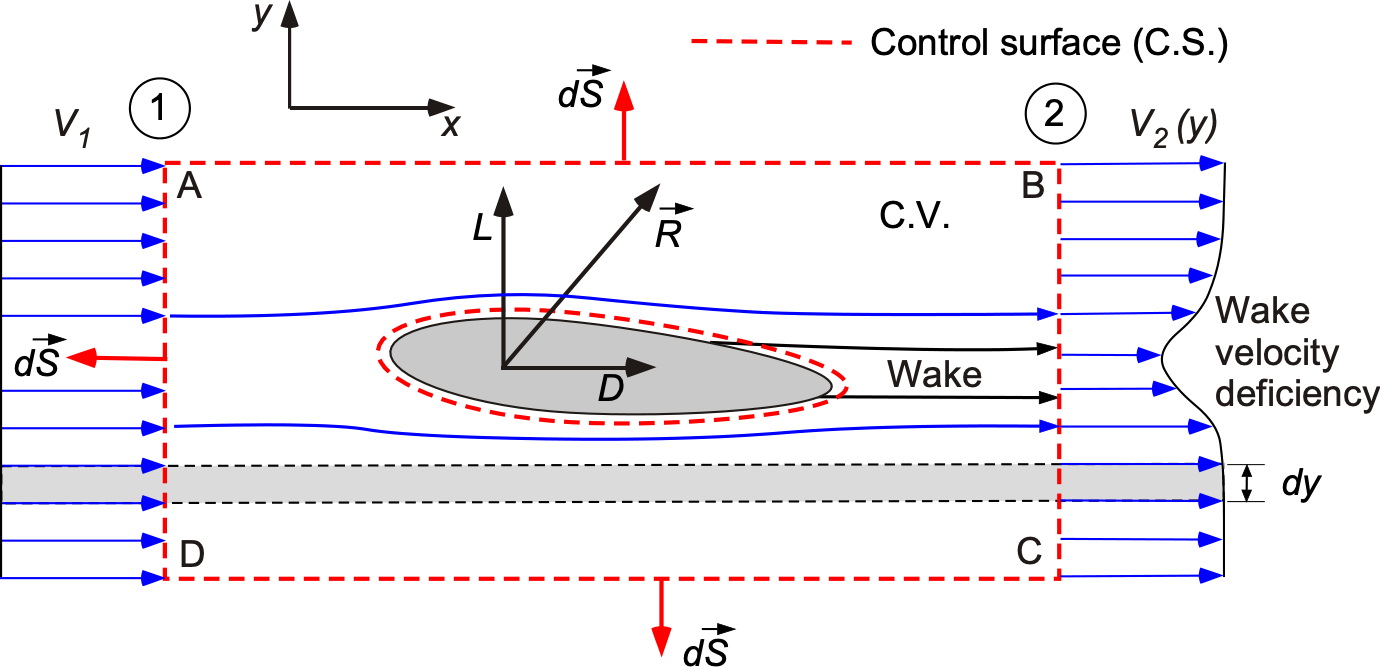

Forces on a Two-Dimensional body

The conservation laws can be used to determine the drag of a two-dimensional body in terms of off-surface fluid properties, e.g., the force on a body in a wind tunnel. Consider the physical problem of a body immersed in a fluid flow, as shown in the figure below. The fluid will generally exert pressure and viscous forces on the body, which are the sources of the resultant force, , and hence the lift,

, and the drag,

. Physically, because of these effects, a wake with a lower flow velocity will form downstream of the body. The objective is to use the equations of motion of the fluid (in this case, continuity and momentum) to calculate the force on the body.

The upstream and downstream sections labeled 1 and 2 and the top and bottom sides bound the control volume. The top and bottom sides of the control volume are considered far enough away from the body that they are in the freestream and, therefore, are streamlines to the flow, i.e., there will be no flow over these boundaries. These boundaries, for example, couldm be the floor and ceiling of a wind tunnel. Remember that points out of the control volume by convention. The upstream or freestream (undisturbed) velocity is

= constant =

. Because of viscosity, a wake of reduced velocity or diminished flow exists behind the body; this gives a wake region a velocity profile in which

.

Consider the forces on the fluid in the control volume. They stem from two sources:

- The net effect of the pressure distribution over the control volume, i.e., over the surface ABCD, then

(57)

- The reaction of the surface forces on the body, i.e., those forces produced over the inner part of the control volume as created by the body, i.e.,

, in accordance with Newton’s 3rd law.

Remember that the flow will exert pressure and shear forces on the body, resulting in a resultant force, . This means that by Newton’s third law, the airfoil will exert a force

on the fluid within the control volume. Therefore, the total force on the fluid volume is the sum of the pressure forces on the control surface and the reaction force of the body on the fluid, i.e.,

(58)

and from the conservation of momentum equation, then

(59)

For steady flow , so that this latter equation is simplified to

(60)

Notice that this latter equation is a vector equation.

Drag Force

To find the drag, the -component of this latter equation is needed, noting that

and

are the inflow and outflow velocities in the

-direction and that the

-component of

is the drag on the section, i.e.,

per unit span. The pressures upstream and downstream are equal, i.e., there is no longitudinal pressure gradient, so that

(61)

Therefore, the force on the fluid and drag on the body can be expressed only in terms of the velocity profiles upstream and downstream, i.e.,

(62)

and so this integral becomes a one-dimensional integral (noting carefully the signs on the components), i.e.,

(63)

The continuity equation can also be applied to the control volume, i.e., based on the principle of conservation of mass, then

(64)

Multiplying by in this case (which is a constant) gives

(65)

Substituting back into the expression for gives

(66)

This latter expression gives the drag of a two-dimensional body in terms of and the flow field properties

and

across a vertical dimension placed downstream of the body.

Notice that is the velocity deficiency or decrement at a given station (or section) in the downstream wake. Also,

is the mass flux, so the product

gives the decrement in momentum. The integral of this expression leads to the total decrement in momentum behind the body and, hence, the drag of the section. If

= constant, then things can be simplified even further to get

(67)

However, some caution is appropriate because this approach works well only without significant flow separation and turbulence from the body. If there are significant losses in the wake that manifest as viscous losses from turbulent eddies, the drag will be underestimated.

This latter technique is frequently employed in wind tunnel testing for measuring forces on relatively streamlined bodies; the velocities downstream of the body or airfoil are measured using what is known as a wake rake. This rake is, in fact, an array of Pitot tubes, which are used to measure the dynamic pressure and the flow velocities in the wake. The momentum deficit is measured at discrete points in the wake, so that the drag per unit span is

(68)

where is the velocity at the

-th point in the wake, and

is the spacing between the measurement points;

does not have to be uniform. The values would be measured for each test point, e.g., different flow speeds and angles of attack.

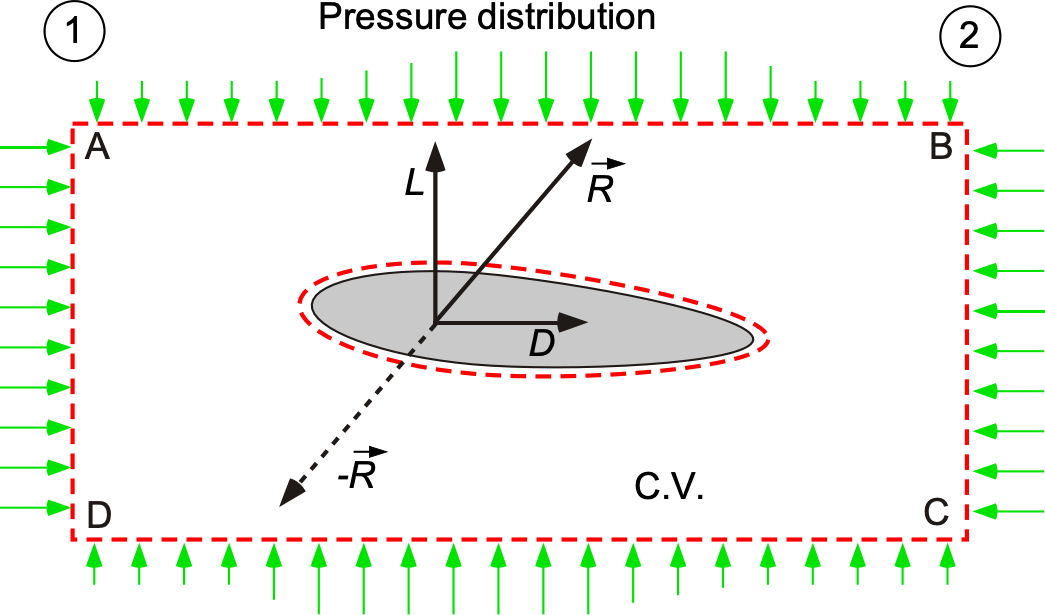

Lift Force

Consider now how to measure the lift on the body, which is the force in the direction. The lift on the C.V. is calculated as the net vertical force resulting from the pressure difference between the suface AB (the ceiling) and CD (the floor), i.e.,

(69)

as illustrated in the figure below, where is the measured pressure distribution (using pressure taps) along the ceiling, and

is the pressure distribution along the floor. Again, while the floor and ceiling are streamlines to the flow there can be a pressure distribution along their lengths from the presence of the body.

The sectional lift per unit span is obtained using a one-dimensional pressure integral along the length of the control volume, i.e.,

(70)

would be located at the start of the test section and

will be at or near the end. Each of the pressure taps would be connected to a pressure measurement system. Because the pressure will be measured at discrete points along the wind tunnel walls, the lift per unit span is given as

(71)

where represents the measurement locations along the wind tunnel, and

is the spacing between measurement points;

can be non-nuniform. This sum is just the area under the

pressure curve between floor and ceiling along the length of the test section.

Historical Context: NACA and Abbott & Von Doenhoff

The integral method was extensively utilized by NACA researchers, notably Ira Abbot and Albert von Doenhoff, whose influential work in the 1940s was published as “Theory of Wing Sections & Summary of Airfoil Data.” Their approach inferred forces from test section wall pressure distributions and wake surveys, eliminating the need for direct surface measurements like pressures on every airfoil. This method allowed over 200 airfoil sections to be tested and compared, significantly benefiting the aeronautics industry by providing a comprehensive catalog of airfoil shapes that could be selected to meet specific aerodynamic requirements.

Summary & Closure

Many fluid flow problems can be analyzed using the continuity and momentum equations in the integral form, as well as the energy equation in the surrogate form of the Bernoulli equation. All three conservation principles will be needed in most practical problems, along with the complete energy equation and the equation of state if compressibility effects are involved. The momentum equation will always be required whenever forces need to be calculated. Problems that can be assumed to be steady, inviscid, and incompressible are the easiest to understand and predict, and to this end, some exemplars have been discussed and solved in this chapter. The experience gained in solving these exemplary fluid flow problems increases confidence in analyzing more complex problems, such as those involving unsteadiness and compressibility effects in a flow.

5-Question Self-Assessment Quickquiz

For Further Thought or Discussion

- Why is the flow through a rapidly converging or expanding Venturi (or duct) more difficult to justify as one-dimensional?

- What happens when an aircraft flies at higher Mach numbers? Does Bernoulli’s equation apply?

- Who was Henri Pitot? What did he do besides invent the Pitot tube?

- Using a drinking straw and a ruler, explain how you would measure the flow velocity in a water channel.

- What happens in the throat of a Venturi as the flow speed becomes subsonic and then supersonic?

- Think about some aeronautical problems that cannot be tackled using the conservation principles in integral form.

- It is proposed that the drag of a circular cylinder is to be measured in a wind tunnel using the momentum deficiency technique. What is the concern here, and why?

- Why does a balloon filled with helium deflate quicker than a balloon filled with air?

- If the drag on a body can be measured using a momentum integral method, how can the lift on the body be measured?

Additional Online Resources

Explore some of these additional online resources to help understand the application of the conservation laws when applied to simple fluid flow problems:

- Explore this interactive simulation of flow through a pipe.

- Video of worked example problems using the conservation laws.

- View this video for a simple experimental demonstration of a U-tube manometer.

- This Pitot Static System Simulator allows you to visualize the Pitot static system on an airplane under varying atmospheric conditions and what happens when system parts become blocked.

- Sadler, D. R. (2005). "Interpretations of Criteria-Based Assessment and Grading in Higher Education." Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 30 (2), 175–194. ↵

- . The diameter of such holes should be less than 0.5 mm or 20-thousandths of an inch. ↵

- Evangelista Torricelli's original derivation can be found in the second book "De motu aquarum" of his "Opera Geometrica." See also: A. Malcherek, "History of the Torricelli Principle and a New Outflow Theory," Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 142 (11), 1–7, 2016. ↵