29 Time-Dependent Flows

Introduction

In fluid dynamics and aerodynamics, a time-dependent or unsteady flow refers to the conditions where the properties (such as velocity, pressure, temperature, and density) at a particular point in space will change with time. This behavior contrasts with steady flow, where the fluid properties at a given point remain constant over time. Unsteady flows occur, and indeed are expected, in many real-world situations, such as when a fluid flow is subjected to changes in operating conditions, when transient events begin, or when time-varying external events produce non-steady forces on flows or flow systems.

In aerospace engineering, unsteady flow effects are frequently encountered. For example, they are found and must be considered to predict fluid behavior in various fields, including aeroelasticity and flutter, rotating machinery (such as jet engines and helicopter rotors), mixing processes, hydraulic and pneumatic control systems, and combustion processes in air-breathing and rocket engines. Analyzing and predicting unsteady flow can be more challenging than steady flow because it requires careful consideration of all relevant time-dependent factors. Closed-form solutions to most unsteady flow problems are generally only realizable in cases with specific assumptions. Therefore, experimental techniques and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) are frequently employed to investigate unsteady flows in various engineering applications.

Learning Objectives

- Understand how to differentiate between steady and unsteady flows and recognize situations in which unsteady flow properties are relevant to problem-solving.

- Know about reduced frequency and Strouhal number, and why they are essential for characterizing unsteady flows and the degree of unsteadiness.

- Be able to apply the conservation principles of fluid dynamics to solve some classic unsteady flow problems.

Classification of Time-Dependent Flows

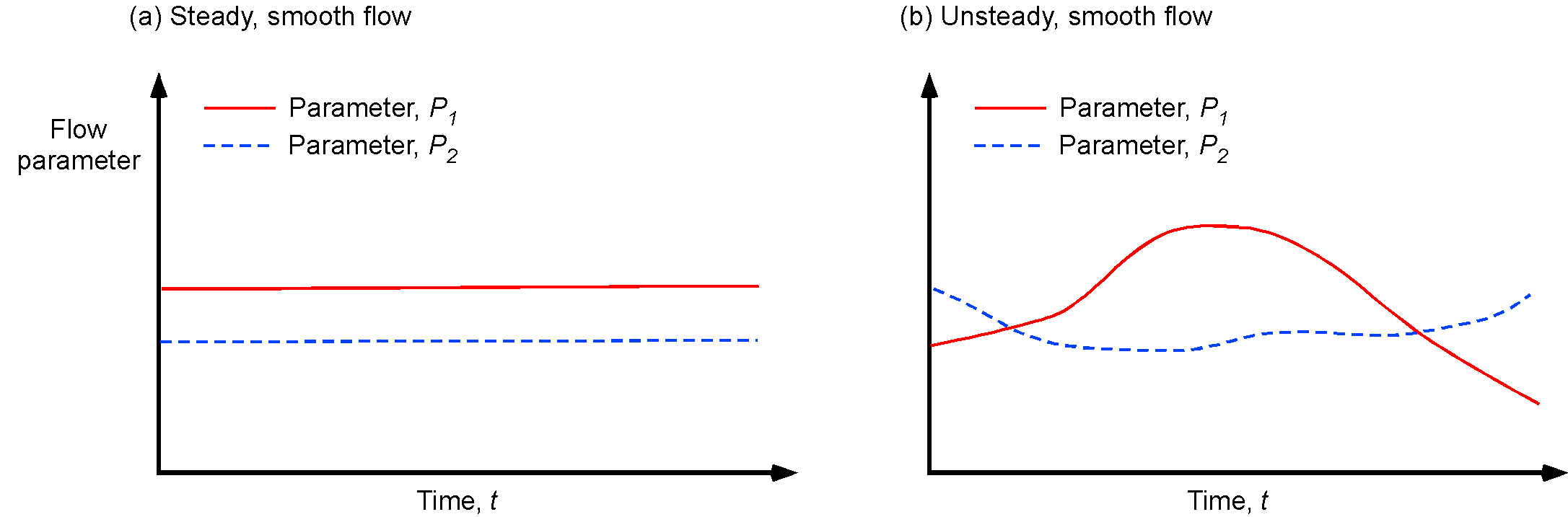

Steady flows are characterized by properties that remain constant over time. A steady-state flow is a condition in which the macroscopic flow properties, such as velocity and pressure at a point, remain constant over time, as shown in the figure below on the left. Mathematically, for steady flows, then

(1)

where is any property such as pressure, temperature, velocity, density, etc. However, in a time-dependent flow, also known as an unsteady flow, the flow properties at a point will change in time, as shown in the figure below on the right. In this case, all of the unsteady terms in any equations used to describe the flow must be retained and solved, i.e.,

(2)

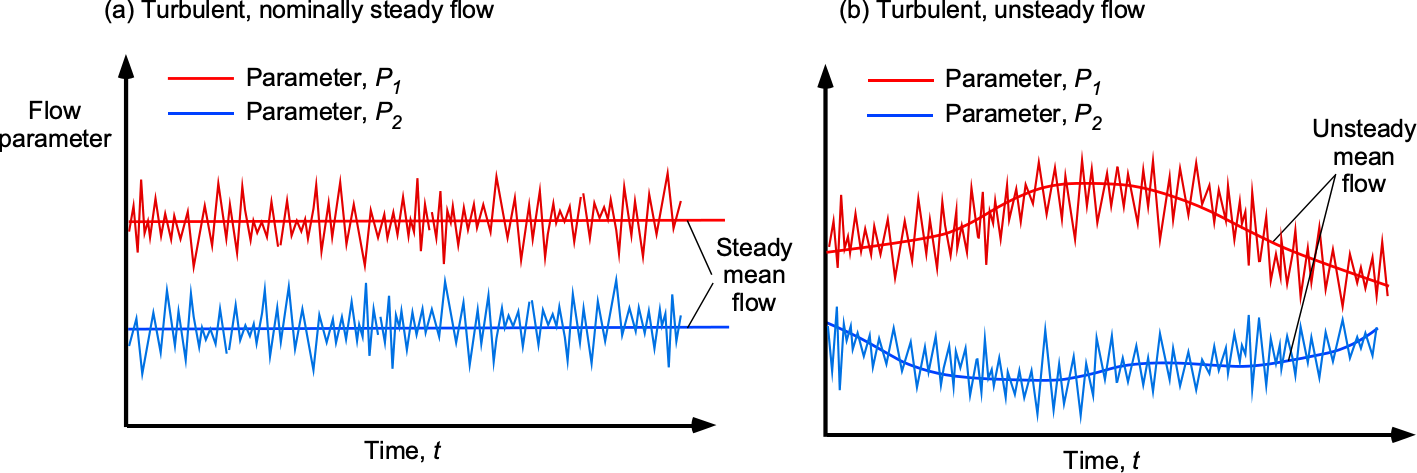

Unsteady flow phenomena are encountered in many engineering applications. Examples include the flows in turbomachinery and other internal combustion engines, helicopter aerodynamics, wind turbines, and numerous problems in aeroacoustics where the creation of time-varying aerodynamic loads produces sound (noise). A turbulent flow is an unsteady flow by definition. However, a turbulent flow can still be statistically steady. This definition implies that the average flow velocity and other quantities remain constant over time, while all statistically varying properties, such as the fluctuating velocity component, remain constant.

The figure below shows the difference between a statistically steady turbulent flow and a statistically unsteady flow. Turbulence enhances fluid mixing, promoting the transport of momentum, heat, and other properties. The irregular motion of fluid particles makes it difficult to predict the behavior of the flow precisely over time; this randomness, or mathematically stochastic behavior, is a fundamental characteristic of turbulence. However, statistically a flow property can be decomposed into a mean or average part,

, and a mean fluctuating part,

, i.e.,

(3)

This latter process is known as a Reynolds decomposition, a concept particularly helpful for modeling turbulent flows.

One reason it is helpful to distinguish between steady and unsteady flows is that the former are often more tractable to understand and predict. Eliminating time from the equations governing fluid flow problems usually results in a significant simplification of both the equations and the mathematical and/or numerical techniques needed to solve them. Characterizing steady, quasi-steady, or unsteady flows is often done using parameters such as the reduced frequency or the Strouhal number.

Strouhal Number

The Strouhal number, given the symbol , is a dimensionless number used in fluid dynamics to characterize the behavior of oscillating or vibrating objects within a fluid flow. It is beneficial for analyzing phenomena such as vortex shedding and sound generation. The Strouhal number is defined as the ratio of the oscillation frequency to the product of the object’s characteristic length (or diameter) and the reference or freestream velocity of the fluid, e.g.,

. The equation is given by

(4)

Notice that the physical frequency (in units of per second or Hz) is used to determine the Strouhal number rather than the circular frequency in the reduced frequency. The Strouhal number is named after the Czech physicist and engineer Vincenc Strouhal, who made significant contributions to the study of oscillating flows in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

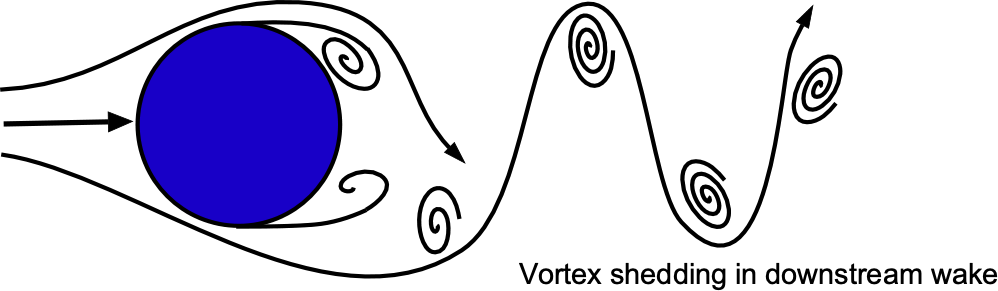

The Strouhal number is often used to analyze various fluid flow phenomena, such as vortex shedding behind a cylinder or other bluff bodies (non-streamlined bodies). It helps characterize the vortex-shedding frequency relative to the fluid flow velocity and the object’s size. For different types of flows and body shapes, there are often characteristic Strouhal number ranges corresponding to specific flow regimes and behaviors, i.e., the behavior locks into a particular shedding frequency.

Check Your Understanding #1 – Calculating the value of the Strouhal number

A circular cylinder with a diameter of 0.1 m is immersed in a fluid flow with a velocity

of 1.0 m/s. The shedding frequency

of vortex shedding behind the cylinder is measured to be 2 Hz. What is the Strouhal number in this case?

Show solution/hide solution.

The Strouhal number is defined by

Using the numerical values gives

The value of 0.2 is often associated with the onset of vortex shedding behind a cylindrical object in a fluid flow. For example, suppose a particular combination of flow speeds and length scales results in a Strouhal number of 0.2. In that case, vortex shedding can be expected, and vortex-induced vibrations on a structure are possible. However, it is essential to note that specific Strouhal numbers may vary across different flow conditions and body shapes.

Reduced Frequency

Another nondimensional parameter used to categorize whether a flow is steady or unsteady is the reduced frequency . The reduced frequency is defined, in general, as

(5)

where is a characteristic physical frequency of the unsteady flow (in units of radians per second),

is a characteristic length scale, and

is a reference flow velocity. Base units should always be used to obtain the correct numerical value for the reduced frequency. For a wing or airfoil, such as one oscillating in angle of attack, the reduced frequency is often defined in terms of its semi-chord, i.e.,

, and the freestream velocity,

, i.e., in this case, it is defined as

(6)

Flows with characteristic reduced frequencies of 0.05 and above are usually considered unsteady, so all unsteady terms must be retained in the governing flow equations. Such problems are more challenging to determine for two reasons. First, the local flow properties also depend on the previous time, i.e., what has happened in the time history of aerodynamic forces. Second, the effects of compressibility may be significant even if the freestream flow velocity is low. This means that the time scales of the unsteady motion become of the order of the propagation speed of pressure disturbances in the flow, which occurs at the speed of sound.

Time-Dependent Fluid Flows

Time-dependent flows are often more challenging to handle in fluid dynamics, but the same principles of conservation of mass, momentum, and energy still apply. Studying exemplars is an excellent way to learn how to solve problems involving unsteady flows. Several classic exemplars in fluid dynamics can be used to establish the solution principles when considering the additional dimension of time.

Torricelli’s Law

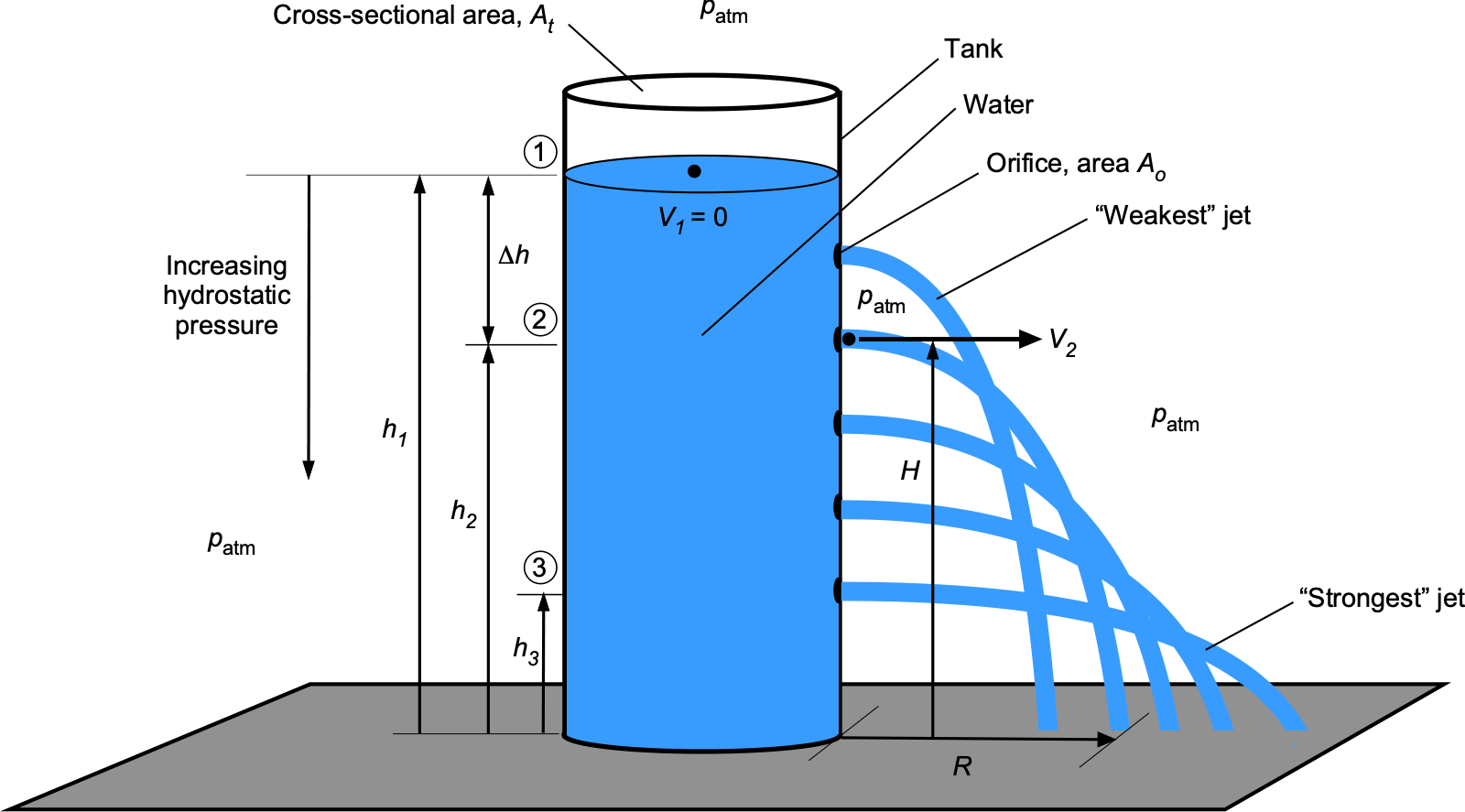

Torricelli’s law relates the velocity of a liquid flowing out of an orifice to the height of the liquid above the orifice’s level, as shown in the figure below. The derivation of this law assumes ideal conditions where the liquid is quasi-steady, incompressible, and inviscid. While the problem is fundamentally unsteady, as the fluid properties at different points in the flow change over time as the liquid drains out of the tank, the time rates of change are small; therefore, the flow can be assumed quasi-steady. Therefore, the applicability of the Bernoulli equation can be considered as it describes the instantaneous balance of energy between different points in the flow.

The application of Bernoulli’s equation between levels 1 and 2 gives

(7)

where is the pressure at the surface, and

is the pressure at the discharge from the orifice. The fluid is a liquid, so

= constant. It is assumed that there are no losses from the discharge through the orifice. Assuming

(i.e., both are equal to atmospheric pressure,

), and

, the Bernoulli equation simplifies to

(8)

Solving for the discharge or “jet” velocity, , gives

(9)

This result shows that the discharge velocity is proportional to the square root of the difference in hydrostatic height or “head” between the free surface at and the orifice at

.

To find the horizontal distance, , reached by a jet from any one of the orifices requires the time,

, it takes for the jet to reach the ground, i.e.,

(10)

where is the height of the orifice above the ground. Therefore, the horizontal distance reached by the jet,

, is given by

(11)

This latter result shows that the distance traveled by the fluid jet depends on the hydrostatic head of fluid above the orifice, , and the height above the ground,

.

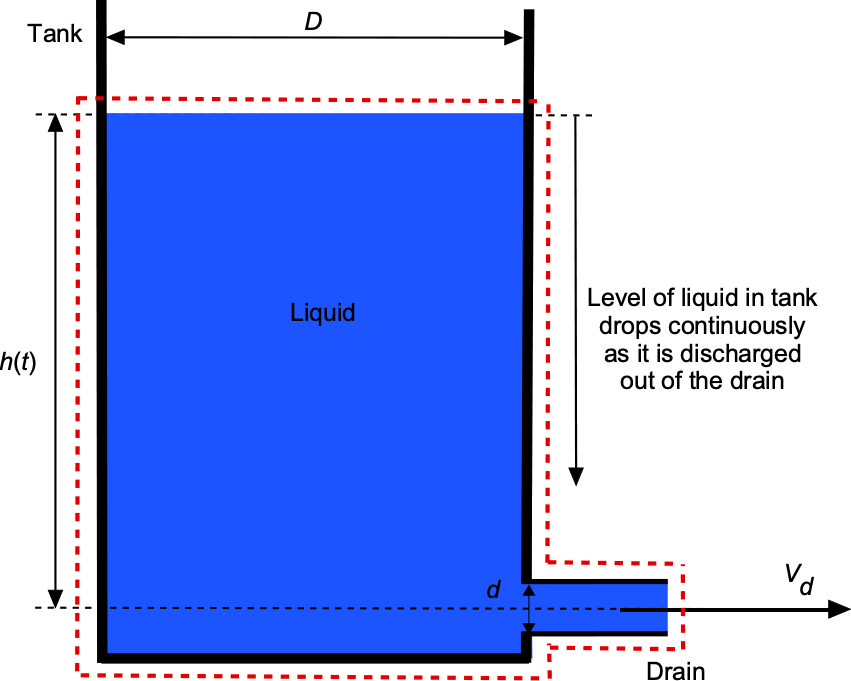

Time for Liquid to Drain from a Tank

Now consider the problem of a tank with a circular cross-section, , that lets a liquid leave through a drain valve at the bottom, as shown below. The discharge velocity,

, of the flow from the drain varies with the height,

, of the fluid level above the drain according to the relationship

. Notice that the height,

, will decrease with time as the liquid leaves the tank.

The application of the continuity equation gives

(12)

where is the area of liquid discharge from the drain. The volume of liquid

in the tank for any height

is

(13)

where is the cross-sectional area of the tank. It is given that

(14)

and this flow rate depends on the instantaneous height of the liquid in the tank, , which, as previously derived, is given by Torricelli’s theorem. Therefore, using the conservation of mass gives

(15)

Separating the variables and integrating them gives

(16)

where the limits of integration are: At , then

, and when

, the tank is considered empty. Performing the integration gives

(17)

In terms of the diameter of the tank, , and the outlet diameter,

, of the drain, then

(18)

Therefore, the time required to empty the tank will be

(19)

where is the initial height of the liquid in the tank when the drain is first opened.

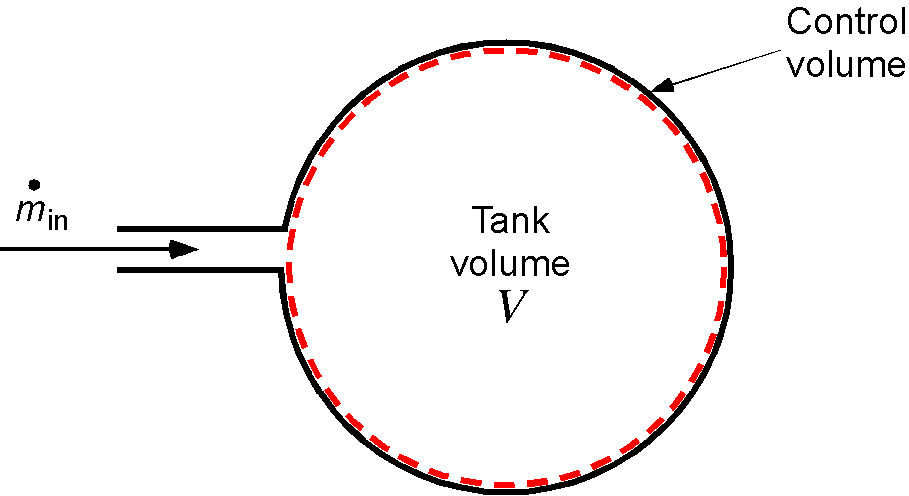

Filling an Air Tank

Consider now a rigid tank of volume with air pumped at a constant mass flow rate, as shown in the figure below. In this problem, the effect of compressibility must be accounted for. Still, it can be assumed that the process is slow enough to be isothermal, and the heat generated by compressing the air is dissipated through radiation by the tank.

This is also an unsteady flow problem because a mass of air is pumped into a fixed volume, and for mass conservation, the air density must increase in time. The initial density and pressure are and

, respectively. The general form of the continuity equation is

(20)

In this case

(21)

and so

(22)

Assume uniform mixing of air, so the density within the volume is uniform. Therefore,

(23)

Integrating using the separation of variables gives

(24)

so that

(25)

which shows that air density increases linearly with time. The corresponding pressure can be obtained from the equation of state, i.e., . If the process is assumed to be isothermal, then

, and so

(26)

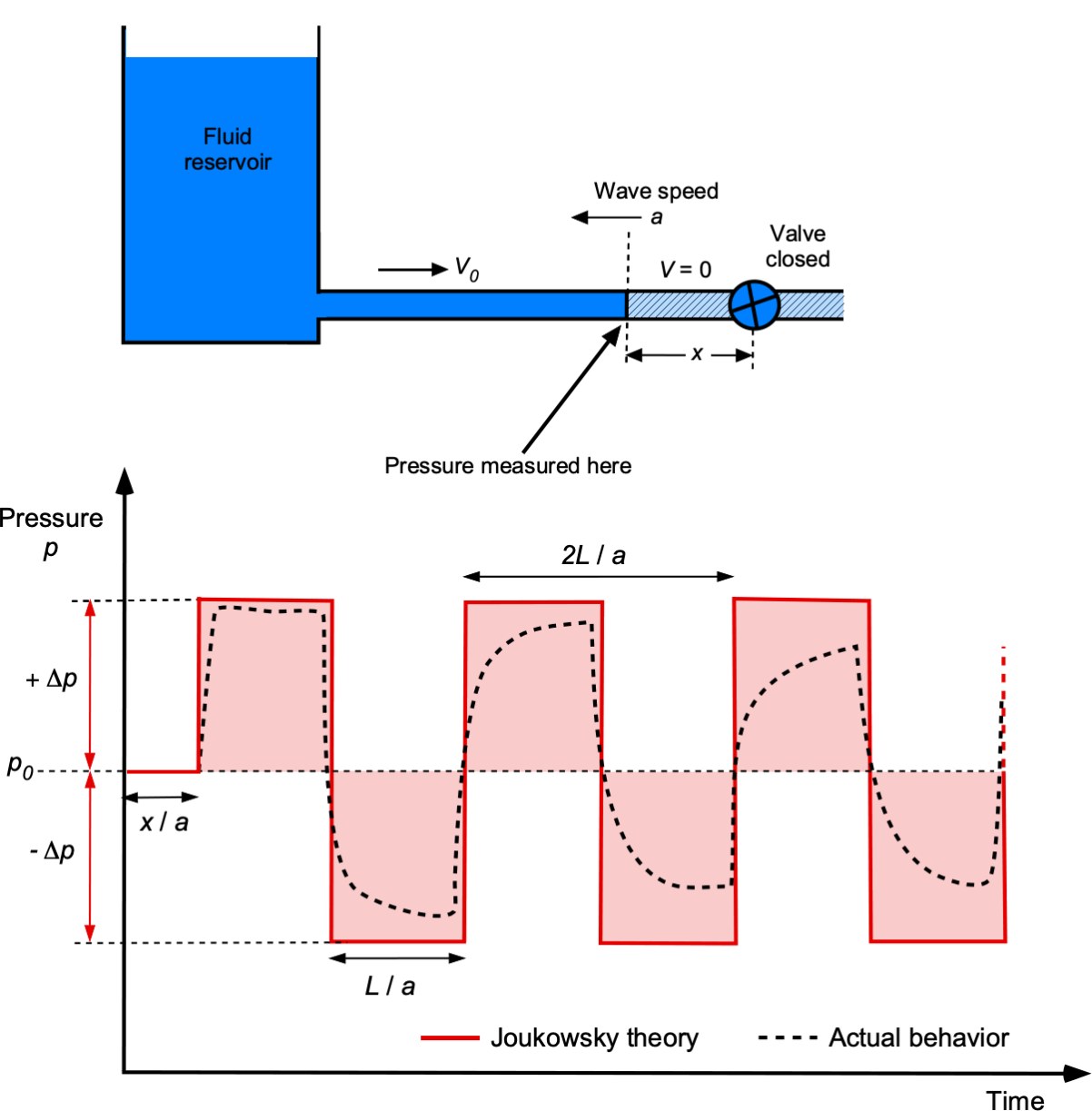

Hydraulic Shock

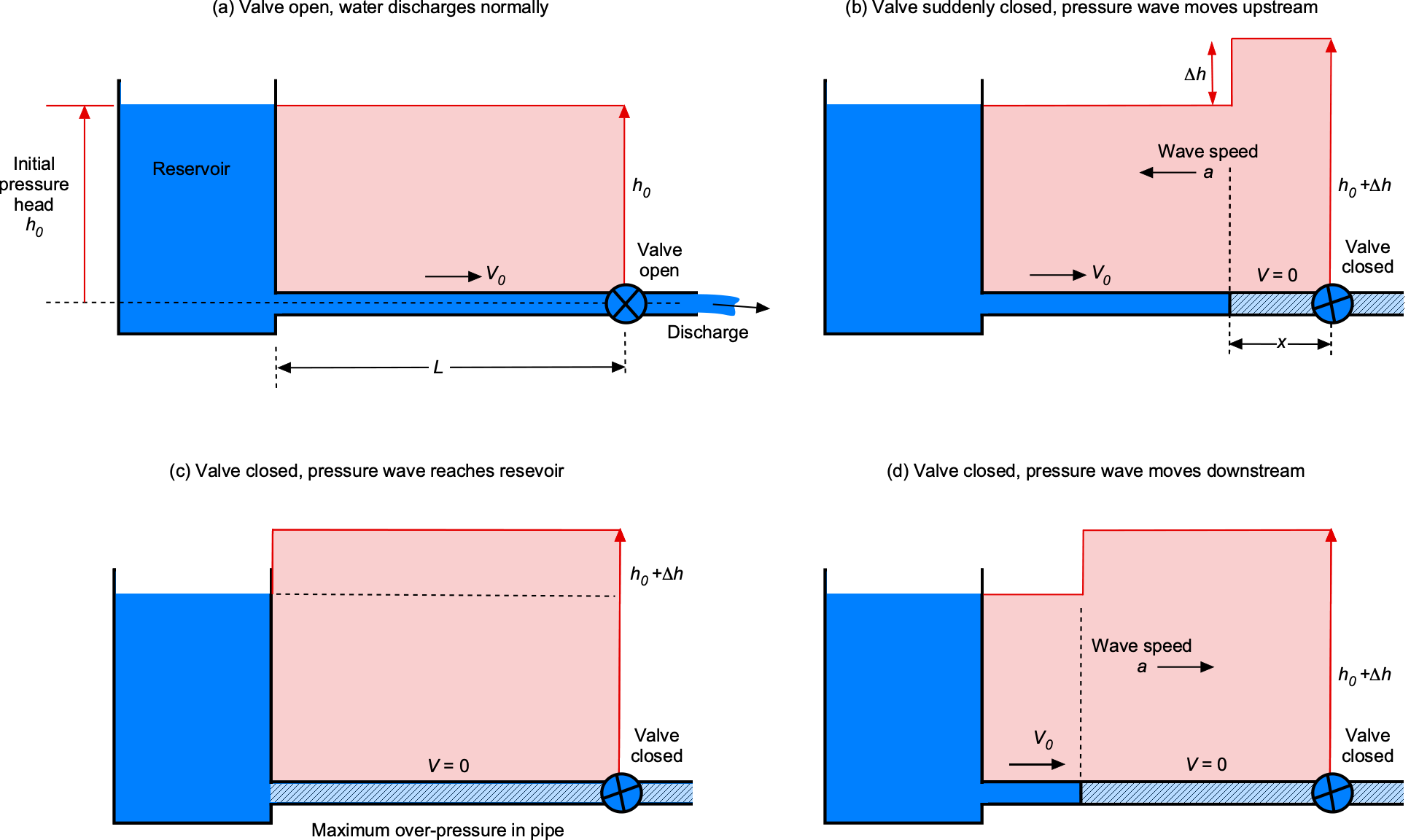

Hydraulic shock, also known as “water hammer” or “hydraulic hammer,” is a time-dependent flow phenomenon that occurs in fluid systems, such as hydraulic and fuel systems, when flow velocity changes suddenly. This abrupt change can result in strong pressure waves propagating through the fluid, causing transient pressure surges within the system, as illustrated in the schematic below. Water hammer is common in fluid flow systems where valves and regulators are rapidly opened or closed. The rapid, time-dependent changes in pressure can generate loud banging or knocking sounds, often audible throughout the piping system.

The fundamental cause of water hammer is the fluid’s inertia and the need for energy conservation when the flow suddenly stops. When a fluid is in motion and experiences a sudden change in velocity, its kinetic energy must be either absorbed or dissipated. If a valve is closed suddenly, the fluid comes to an abrupt stop, converting all its kinetic energy into increased pressure; the flow then stagnates in the pipe.

This process creates a pressure wave that travels back upstream through the pipe. This pressure wave moves through the fluid at the speed of sound in the medium, , known as the wave speed. When the pressure wave reaches a point where the fluid is stagnant, such as the reservoir, the higher pressure head restarts the wave downstream, causing continued oscillations until the wave’s energy is dissipated through friction. The increase in pressure causes a “hammer” effect, i.e., a thumping effect, which can be felt and/or heard by an observer.

The resulting pressure pulses can be several times higher than the normal operating pressure. The change in pressure from the water hammer depends on several factors, including the speed at which the valve is closed, the type of fluid, the length of the pipe, its elastic properties, and how the pipe is mounted, such as whether it is supported at its ends and/or clamped along its length. Prolonged or severe water hammer can cause structural damage to pipes, fittings, and other system components. The phenomenon can cause fatigue, leaks, and pipe bursts, as well as accelerate the wear and tear on valves and pumps, thereby increasing maintenance requirements. Preventing or mitigating water hammer effects involves implementing engineering solutions and using devices like surge tanks, air chambers, and water hammer arrestors, which are designed to absorb excess pressure and prevent damage to the system.

Consider the analysis of this problem. A liquid stored in a tank flows steadily through a pipe of length , as shown in the figure below. At the time

, the valve at the downstream end is quickly closed, producing the classic pressure pulse of a water hammer. Water hammer transients are typically axisymmetric because the axial mass, momentum, and energy changes are significantly more significant than their radial counterparts.

Nikolay Joukowsky laid the foundation of the water hammer theory[1] where the pressure amplitude, , in the liquid in the pipe is related to the change in flow velocity,

, using

(27)

where is the wave propagation speed (assumed to be constant) and

is the fluid density; this equation is commonly referred to as the piston theory. The negative sign in Eq. 27 describes a water hammer wave moving downstream, while the positive sign describes the wave moving upstream. Because pressure head is often used in the field of hydraulics, Eq. 27 can also be written as

(28)

There are three cases of interest when it comes to predicting water hammer effects, all of which involve the wave propagation speed:

- Gradual closure of the valve.

- Sudden closure of the valve.

- Closure of the valve with allowance for the elasticity of the pipe, which affects the wave propagation speed.

The transit time, also known as reflection time, taken for the pressure wave to propagate from the valve to the tank and then back to the valve, will be

(29)

If the time it takes to close the valve is , then if

, it is longer than the reflection time, and the valve closure is considered gradual. If

is shorter than the time

, the reflection of the valve closure is referred to as being sudden.

If , which is a gradual closure of the valve, then the increase in pressure from the water hammer is given by

(30)

is the average flow velocity inside the pipe before the valve closes. The equivalent pressure head of the water hammer is

(31)

If , which is a sudden closure of the valve, then the increase in pressure from the water hammer is given by

(32)

and the equivalent pressure head is

(33)

where represents the average flow velocity of the fluid inside the pipe before the valve is closed. This velocity is critical in determining the magnitude of the pressure increase caused by the water hammer effect. It reflects the kinetic energy of the moving fluid that is converted into pressure when the flow is suddenly stopped.

Notice that in both cases, the propagation speed of the pressure wave, , is needed. If the pipe is rigid, then

(34)

where is called the bulk modulus of the liquid, for which values for various liquids are available. This latter equation is often referred to as the Newton-Laplace equation.

If the pipe is elastic, which most will be to a lesser or greater degree, then

(35)

where is called the effective bulk modulus of the liquid in the pipe. The value of

can be obtained using

(36)

where is the modulus of elasticity of the pipe,

is the pipe diameter, and

is the wall thickness of the pipe. The value of

depends on exactly how the pipe is mounted and anchored; usually

. The modulus of elasticity of the pipe is a material property for which values are also widely available.

Finally, consider the valve’s sudden closure when the pipe’s elasticity is taken into account. In this case

(37)

Therefore, the system’s elasticity mitigates the pressure effects of the water hammer.

Check Your Understanding #2 – Determining hydraulic shock pressure in a pipeline

A hydraulic fluid with a density flows through a titanium pipe in an aircraft’s hydraulic system. The pipe has a diameter of

and a wall thickness of

. The bulk modulus of the hydraulic fluid is

, and the modulus of elasticity of titanium is

. The hydraulic fluid has an average velocity

before a valve is suddenly closed in the system. Assume

. Calculate the pressure increase

in the pipe from the hydraulic shock (water hammer) effect.

Show solution/hide solution.

To calculate the pressure increase, we first need the wave speed , which depends on the effective bulk modulus

, i.e.,

where is calculated using

Substituting the given values into the equation for gives

The wave speed, , can now be calculated, i.e.,

The pressure increase from the water hammer effect (sudden valve closure) is given by

Substituting the known values gives the change in pressure as

Why is the speed of sound so much higher in a liquid than in air?

The speed of sound in a medium, whether it’s a gas, liquid, or solid, depends on the properties of that medium. Sound travels faster in liquids and solids than in gases because the molecules in these substances are much closer together, allowing for the more rapid transmission of mechanical waves. The speed of sound in a medium is determined by its density and elastic properties, specifically its bulk modulus. The bulk modulus measures a substance’s resistance to compression or expansion under pressure. Liquids and solids generally have higher bulk moduli than gases, making them less compressible. In a liquid, the molecules are closer together than in a gas, and they can still transmit mechanical waves. This close molecular packing and the resistance to compression contribute to a higher sound speed in liquids than in gases.

Producing Jet Thrust

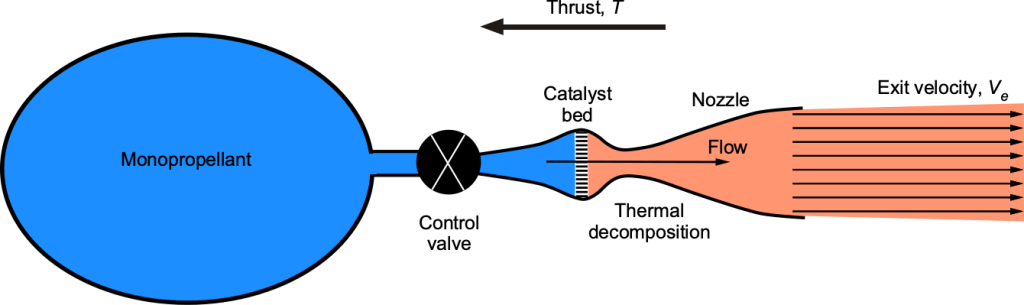

A monopropellant thruster is a basic rocket, often used for satellite propulsion and control, that stores a propellant mass under pressure in a pressurized tank. The propellant is released over time by opening the valve, allowing it to flow over a catalyst bed. This process causes thermal decomposition and the liberation of energy from the propellant, as shown in the figure below. The flow then expands through a nozzle to produce an exit velocity and, hence, a thrust resulting from the time rate of change of the momentum of the expanding gases. The idea is that the thrust increases the satellite’s orbital velocity and altitude.

This is a time-varying flow problem because propellant mass is continuously discharged from a tank, reducing the propellant mass within the control volume. The most general form of the continuity equation is

(38)

In this case, it can be reduced to

(39)

where is the mass of the propellant and

is the propellant flow rate. Notice that the minus sign occurs because the total propellant mass is decreasing.

Let the initial mass of the spacecraft be . Conservation of mass gives the current mass of the spacecraft,

, at time

later, as the propellant is discharged as

(40)

where = constant. The thrust force from the propulsion system is given by Newton’s second law (force equals time rate of change of momentum), i.e.,

(41)

and so the acceleration of the spacecraft, which is not constant because of its continuously decreasing mass, is given by

(42)

Therefore,

(43)

Integrating the equation gives

(44)

which has a special name called the rocket equation.

Check Your Understanding #3 – Discharge of a monopropellant thruster

An orbiting satellite is propelled using a monopropellant thruster. The satellite has an initial mass of 5,000 kg, including its propellant mass. To give a slight corrective boost to its orbit, it opens the control valve and ejects propellant at a constant rate of 0.1 kg/s, with an effective exit velocity of 2,000 m/s. Assume the satellite operates in a vacuum, with no gravitational forces acting on it. Determine the thrust, the change in velocity of the satellite, and the new mass after 90 seconds from the start of the propulsive burn.

Show solution/hide solution.

The thrust produced can be determined from the time rate of change of momentum of the exhaust gases, i.e.,

After 90 seconds of thrusting, i.e., = 90, then using the rocket equation gives

The final mass after the burn will be

Summary & Closure

Unsteady flows, characterized by fluctuations in fluid properties over time, are a fundamental aspect of fluid dynamics and are especially relevant across many engineering and scientific disciplines. Unlike steady flows, unsteady flows are more representative of real-world scenarios where conditions are rarely constant. Studying unsteady flows is essential for designing and optimizing advanced aerodynamic systems, propulsion technologies, and other applications where time-dependent behavior is critical. The practical implications of unsteady flows extend beyond fundamental fluid dynamics, impacting areas such as turbulence modeling, wave propagation, and the transient behavior of fluid systems. Addressing these complexities requires sophisticated mathematical models and computational methods capable of capturing transient phenomena. An essential step in analyzing unsteady flows is their classification, often achieved using dimensionless parameters such as the reduced frequency, which helps quantify the degree of unsteadiness relative to the system’s inherent time scales. Throughout this chapter, various classic examples have illustrated the principles of solving simple unsteady flow problems. This understanding is crucial for developing accurate predictions and practical solutions in applications where unsteady flows are a key consideration.

5-Question Self-Assessment Quickquiz

For Further Thought or Discussion

- Can you provide real-world situations where unsteady flow is crucial in fluid systems or engineering applications?

- Why is reduced frequency an essential parameter for analyzing fluid flow oscillatory or vibratory motion?

- In what scenarios might the Strouhal number be a relevant parameter to consider?

- How does turbulence contribute to the complexity of fluid dynamics, and why is it often associated with unsteadiness?

- Discuss the practical implications of unsteady flows in engineering design. How might engineers account for unsteady conditions in the design of systems like pipelines, aircraft, or water turbines?

- How might unsteady flows impact the efficiency and performance of propulsion systems, such as those in aircraft or marine vehicles?

Other Useful Online Resources

To learn more about unsteady flows, take a look at some of these online resources:

- A good video explaining the differences between steady and unsteady flows.

- An explanation of unsteady flows, including the effects of thermodynamics.

- An explanation of the conservation of mass in unsteady flow.

- A video presentation on the application of the continuity equation to unsteady flows.

- Joukowsky, N., “Über den hydraulischen Stoss in Wasserleitungsröhren.” (“On the hydraulic hammer in water supply pipes.”) Mémoires de l'Académie Impériale des Sciences de St.-Pétersbourg, Series 8, 9(5), 1-71, 1900 (in German). ↵