56 Rockets & Launch Vehicles

Introduction

Rockets launch payloads, such as satellites and space probes, into Earth orbit. Launch vehicles are highly specialized and tailored to specific missions and payloads. For example, some launch vehicles are designed to place payloads such as satellites into low Earth orbit, while others are intended to send spacecraft into deep space. The choice of launch vehicle will depend on factors such as the desired orbit, payload mass, and size. In addition to military and civilian applications, there is also a growing interest in commercial and tourism-related payloads. Companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin are developing launch vehicles for both commercial satellite launches and human spaceflight, potentially opening space to a broader range of users and applications.

Solid- and liquid-propellant rocket engines are commonly used in launch vehicles and can be combined to achieve specific performance characteristics. Solid-fuel rocket boosters can provide high initial thrust at liftoff. In contrast, liquid-propellant engines can provide more precise control of thrust and greater efficiency once the vehicle is in flight. In addition, the number of stages in a launch vehicle can vary depending on the mission requirements. Some launch vehicles have only one stage, while others have multiple stages that are separated sequentially during flight. The multi-stage approach enables the payload to achieve higher velocities and altitudes with less propellant than a single-stage rocket design.

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the various types of rockets and launch vehicles, as well as their applications in space missions.

- Know how to derive and use the rocket equation to solve simple problems, such as determining burnout velocities.

- Understand the staging process and its use for launch vehicles.

- Know about missiles and the ballistics of projectiles.

Types of Rockets

There are various types of rockets designed for different purposes and applications. Launch vehicles transport payloads into space. Commercial rockets provide satellite launch services, with some models featuring partial reusability to reduce operational costs. Crewed spacecraft launch vehicles, such as SpaceX’s Falcon 9, can transport humans into orbit. Space probes explore celestial bodies, suborbital rockets facilitate space tourism, and military rockets and missiles serve in defensive and offensive roles. Experimental rockets, such as research and hobbyist rockets, are designed to support scientific experiments and personal projects. The diversity in rocket types reflects the multifaceted nature of space exploration, defense, and scientific research.

Launch Vehicles

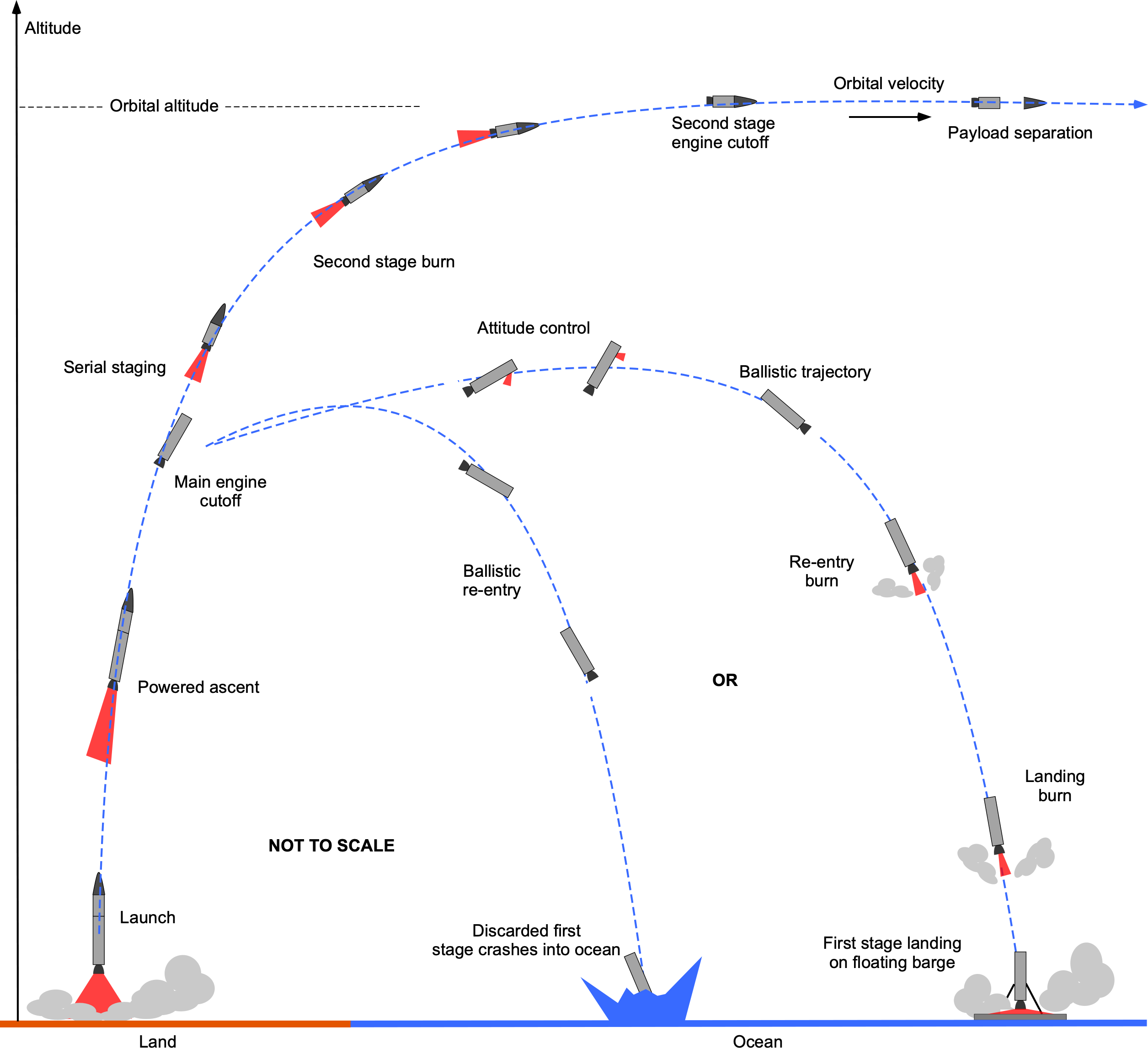

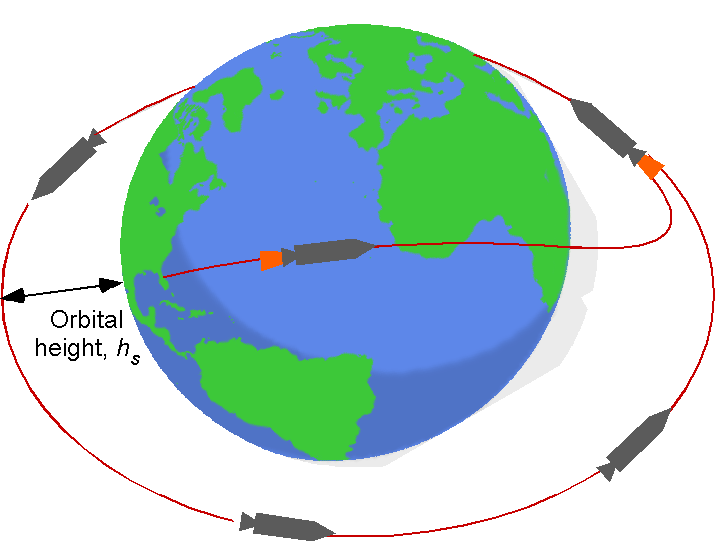

A representative launch profile of a rocket designed to send a payload into space is shown in the figure below. At launch, the thrust from the engines will exceed the rocket’s weight, allowing it to accelerate quickly away from the pad. The rocket’s weight rapidly decreases from its high propellant consumption, allowing it to continue accelerating as it gains altitude. As the rocket begins to exit the atmosphere, at about 60,000 ft (approximately 20,000 m), it will fly at supersonic speeds. It also begins to pitch into a more horizontal flight path, and the rocket gains translational velocity, allowing the payload to reach its initial equilibrium orbital velocity and altitude.

Several minutes into the ascent, staging occurs, during which the first stage is jettisoned and the second-stage rocket engine is ignited. The first stage then falls back to the surface and either burns up in the atmosphere (depending on the staging altitude) or breaks apart and crashes into the ocean. In exceptional cases, the first stage may be recovered; solid rocket boosters are usually recovered by parachute and may be reused.

The upper stage (or stages) then continues to accelerate into space. The rocket engines will cut off as the payload reaches the required initial orbital velocity and altitude, which is known as a parking orbit. A second burn is then performed after the orbit has stabilized, placing the spacecraft into its final orbit. At this point, the payload, such as a satellite, is deployed. Rendezvousing a spacecraft with the International Space Station (ISS) involves a series of precise maneuvers to match the ISS’s orbit. The spacecraft gradually approaches the ISS, conducting proximity operations to ensure alignment. During the final approach, automated systems and minor thruster adjustments guide the spacecraft to a gentle docking with the International Space Station (ISS).

Spacecraft

Spacecraft are utilized in various applications. Some are designed for specialist missions, such as planetary exploration or Earth observation, while others have a more general-purpose application and can be used for multiple tasks. Spacecraft typically consist of numerous subsystems and components, including a payload (the primary equipment or instruments for the mission), a propulsion system (for maneuvering and adjusting the spacecraft’s trajectory), communication systems (for transmitting and receiving data), and power systems (such as solar panels or batteries).

One essential function of a spacecraft is orbit insertion, which involves placing the spacecraft into a specific orbit around a planet or other celestial body. This goal requires a carefully planned trajectory and precise firings of the rocket engines to achieve the desired orbit. However, spacecraft can be highly complex and require extensive testing and development on Earth to ensure reliability and safety in space. This work involves testing in simulated space environments and rigorous quality control procedures to ensure that all components meet strict performance standards. This approach minimizes the risk of malfunctioning in space, which can be disastrous and result in substantial financial loss.

Missiles

Missiles can be broadly categorized into two main types: ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. Ballistic missiles are used for long-range strikes against threats. They are launched high into the upper atmosphere or the fringes of space, following a parabolic trajectory before reentering the atmosphere and striking their target. Ballistic missiles can be easier to intercept than cruise missiles because they follow a predetermined flight path that is challenging to alter after the launch.

Cruise missiles are designed to fly at low altitudes and to follow more maneuverable flight paths to evade threats and defenses. They can be launched from various platforms, including aircraft, ships, and ground-based launchers. Cruise missiles can be more challenging to detect and intercept because they fly at lower altitudes than ballistic missiles and are fast and highly maneuverable.

In addition to their propulsion system, targeting, guidance, and warhead systems, missiles require advanced sensors and communication systems to navigate accurately to their targets and avoid obstacles. Consequently, missiles are highly complex weapons systems that require extensive testing and development to ensure their reliability and effectiveness. In addition, they are subject to strict regulations and controls, and their use is governed by international law.

Miscellaneous Types of Rockets

Sounding rockets gather data on atmospheric conditions, such as temperature, pressure, and wind speed, at altitudes that are difficult to reach with aircraft or balloons. They are typically small, single-stage rockets launched into suborbital trajectories, carrying scientific instruments and sensors to collect various types of data.

Jet-Assisted Takeoff (JATO), also known as Rocket-Assisted Takeoff (RATO), is a technique that utilizes rockets to provide additional thrust during an aircraft’s takeoff, particularly when the aircraft is heavily loaded or operating from a short runway. The rocket engines temporarily boost the aircraft’s acceleration, helping it take off and climb. The most famous RATO aircraft is a modified Lockheed Martin C-130 Hercules. This four-engine turboprop military transport airplane has served as a utility aircraft for the Blue Angels. The RATO system features solid rocket engines mounted on the sides of the aircraft’s fuselage.

Rockets are also used to provide emergency lifelines to ships that are in distress. In this application, a rocket-powered line is fired from shore or another ship to the stranded vessel, enabling rescuers to establish a connection and provide assistance. Rockets could also deliver relief materials to inaccessible areas during natural disasters or humanitarian crises. However, this approach would require the development of reliable, cost-effective rocket delivery systems, along with appropriate infrastructure and logistical support.

Rocket Equation

The rocket equation is widely used in rocket sizing and estimating propellant loads. The Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who published it in 1903 in his work on spaceflight theory, is credited with deriving it. However, Robert Goddard and Hermann Oberth also derived the rocket equation independently of Tsiolkovsky (and each other) during the 1920s.

Derivation

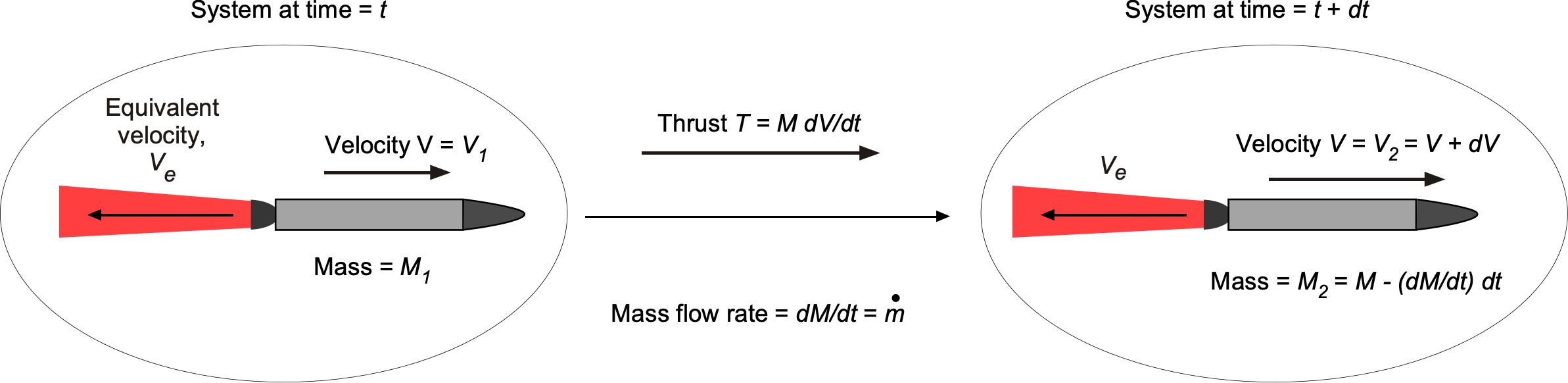

Consider an accelerating rocket of mass propelled by the engine’s thrust, as shown in the figure below. Using Newton’s second law, then

(1)

where is the acceleration of the rocket. The forces from gravity and atmospheric drag have been neglected relative to the rocket’s weight, so the equation is strictly valid for a rocket in space. However, it is not an unreasonable approximation, even when considering flight in the atmosphere.

The thrust produced by the rocket motor is

(2)

where is the mass flow rate of the propellant during the burn, and

is the equivalent exhaust velocity from the rocket motor’s nozzle. Using Eq. 2, then

(3)

which gives the acceleration of the rocket during the burn as

(4)

The change in mass of the rocket is (from the use of propellant), so the time rate of decrease of mass is equal to the mass flow rate, i.e.,

(5)

so that

(6)

Separating the variables and integrating them over the burn time gives

(7)

where and

are the initial mass and velocity of the rocket at

, respectively, and

and

are the final mass and velocity, respectively, at time

.

After integration of the previous equation, the change in the velocity of the rocket is

(8)

This latter equation, known as the rocket equation, is highly useful in mission performance analysis and vehicle sizing. In some ways, it is analogous to the Breguet equations used in aircraft performance analysis. Notice that is given by

(9)

where is the mass of propellant used.

The rocket equation is often written in terms of the initial mass, , and the burnout mass,

, i.e., the mass of the rocket after the propellant is fully expended, as

(10)

where is the initial velocity, and the burnout velocity is

. For a launch vehicle, its initial velocity on the pad is zero (

), so the burnout velocity for the rocket (or the first stage) will be

(11)

Effects of Gravity

If gravity losses are included (but no aerodynamic drag losses) in the case of a pure vertical launch, then the rocket equation in Eq. 10 is modified to

(12)

The second term, , is referred to as the gravity loss. Notice that for a rocket going up vertically, the gravity loss term reduces the attainable velocity of the rocket at the burnout time, i.e.,

(13)

where is standard gravity, which is equal to 9.81 m/s

or 32.17 ft/s

. Therefore, the rocket equation with the gravity loss term becomes

(14)

If the rocket follows a curved trajectory and pitches over at a local trajectory angle (with respect to the horizon) as it increases altitude, then the gravity loss term is

(15)

where when the rocket flies vertically and

when it flies horizontally. However, properly evaluating this latter term requires more specific information about the launch profile, i.e.,

. Neglecting the gravity loss term is usually justified as its value is relatively small compared to the

obtained by burning the propellant.

Burnout Height

For a single-stage rocket, the vertical height achieved at the burnout time, , is

(16)

If the flight velocity, , is given by

(17)

then the height achieved at is

(18)

After integration, then

(19)

Rocket Mass Breakdown

The initial mass of the rocket vehicle can be written as the sum

(20)

where is the mass of the propellant,

is the structural mass of the rocket, and

is the mass of the payload. The burnout mass is reached when all of the propellant is exhausted, which is given by

(21)

As in most engineering fields, it is convenient to use dimensionless quantities. For rockets, the initial mass-to-burnout mass ratio, , is defined as

(22)

Likewise, the payload ratio, , is defined by

(23)

Finally, the structural mass coefficient, , is defined by

(24)

In light of these preceding definitions, it can be shown that the mass ratio is given by

(25)

Therefore, in terms of the mass and payload ratios and the structural mass coefficient, then

(26)

Payload mass ratios can vary significantly depending on the mission objectives, destination, and launch vehicle configuration. However, historical data show that structural mass coefficients are relatively consistent across various rockets and launch vehicles. The structural mass coefficient, denoted by , represents the structural mass ratio to the stage’s initial mass. Its approximate constancy among different vehicle designs is convenient for preliminary design studies, where an estimated value of

can be assumed without requiring a detailed structural analysis. Typical values of

for various launch vehicles are listed in the table below.

| Vehicle Type | Typical Structural Mass Coefficient (ε) |

|---|---|

| Solid rocket stages | 0.09–0.12 |

| Liquid rocket stages (expendable) | 0.07–0.10 |

| Liquid rocket stages (reusable) | 0.10–0.15 |

| Upper stages (lightweight) | 0.04–0.08 |

| Heavy-lift first stages | 0.08–0.12 |

| Reusable boosters (e.g., Falcon 9 first stage) | 0.12–0.18 |

Structural Mass Breakdown

The structural mass of a rocket includes all components necessary to support and operate the propulsion and payload systems, excluding the propellant and payload themselves. Structural mass includes the propellant tanks, interstage structures, primary load-bearing frames, thrust mounts, and aerodynamic fairings. It also includes the mass of the propulsion feed systems, pressurization systems, avionics, wiring, thermal protection systems, and, for reusable vehicles, landing gear and recovery hardware. The propellant tanks must withstand internal pressures and dynamic loads during flight, often requiring significant reinforcement, particularly in cryogenic applications where thermal insulation is also necessary. Interstage adapters and bulkheads transfer thrust and aerodynamic loads between different stages while maintaining structural integrity under varying stress conditions.

The thrust structure mounts the engines and transmits their loads to the rocket body, often accounting for a substantial portion of the total structural mass. Aerodynamic fairings protect the payload during ascent through the atmosphere and must be lightweight yet capable of surviving aerodynamic and acoustic loading. Pressurization systems, such as helium tanks used to maintain tank pressure during propellant depletion, add additional mass. Avionics and wiring, although individually lightweight, add up to a non-negligible fraction of the total structure when distributed throughout the vehicle. Thermal protection systems, particularly for re-entry vehicles, contribute to the structural mass by adding heat-resistant materials. In modern reusable rockets, additional mass is incurred by descent-control and landing structures, such as grid fins, reaction control thrusters, and deployable landing legs. The structural mass must be minimized to maximize payload capacity while meeting stringent requirements for strength, stiffness, and durability.

Impulse

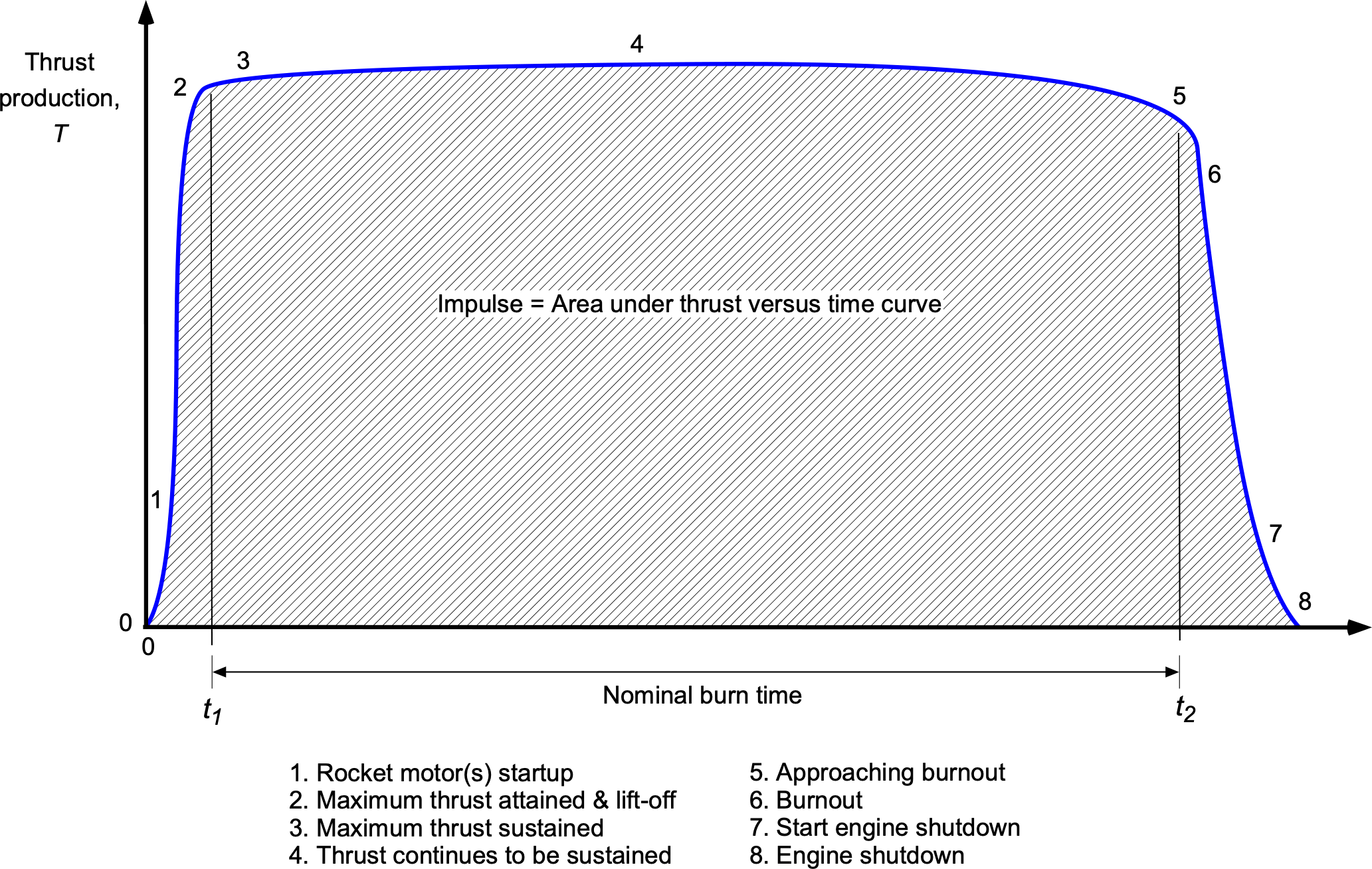

The total impulse is defined as the integral of the thrust over its burnout time, , i.e., the time for which the rocket engine runs. The total impulse is given by

(27)

as illustrated graphically in the figure below. Notice that the impulse is the area under the thrust/time curve.

If and

are constant, as is often a good approximation, then

(28)

where is the mass of the propellant burned. The total impulse, therefore, will be equivalent to the net momentum imparted to a rocket by the engine(s) during the burn.

Specific Impulse

The measure of efficiency used in most rocket performance calculations is the specific impulse, which is the total impulse produced divided by the propellant used in terms of its weight. The specific impulse is a property of the propellant’s chemical composition and can be evaluated using a thermodynamic analysis. In general, one wishes to carry as little propellant as possible, so the idea is to have a rocket with a high specific impulse.

The specific impulse, , is defined as

(29)

Therefore, the higher the value of , the more efficient the rocket motor will be in producing thrust. It will be noted that the specific impulse for the rocket motor is analogous to the specific fuel consumption for an air-breathing engine. It is further apparent using Eq. 2 that if the thrust is approximately constant, then

(30)

where it will be noticed that has units of time (seconds).

Therefore, the specific impulse is the total impulse (or change in momentum delivered) per unit weight per unit time of the propellant consumed, which is a measure of the efficiency in producing thrust. The equivalent exhaust velocity, , depends to a large extent on the chemistry and efficiency of the combustion of propellant. High combustion temperatures, achieved with low-molecular-weight propellants, are essential for achieving the highest specific impulse. To this end, the most widely used propellants are liquid hydrogen (LH2) and liquid oxygen (LO2 or LOX), as summarized in the table below.

| Fuel / Propellant Combination | Rocket Type | Specific Impulse (s) | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium perchlorate composite propellant (APCP) | Solid rocket motor | 240–290 | Sea level |

| RP-1 (kerosene) / Liquid oxygen (LOX) | Liquid bipropellant | 280–310 | Sea level |

| Liquid hydrogen (LH₂) / Liquid oxygen (LOX) | Liquid bipropellant | 370–465 | Sea level / Vacuum |

| UDMH / Nitrogen tetroxide (N₂O₄) | Hypergolic bipropellant | 290–320 | Vacuum |

| Hydrazine (monopropellant) | Monopropellant thruster | 220–240 | Vacuum |

| Xenon (electric ion propulsion) | Ion thruster | 2,000–5,000 | Vacuum |

| Liquid methane (CH₄) / Liquid oxygen (LOX) | Liquid bipropellant | 360–380 | Vacuum |

| Graphite-based solid propellant | Solid rocket motor | 200–250 | Sea level |

| Hydrogen / Nuclear thermal propulsion | Nuclear rocket engine | 800–900 | Vacuum |

Check Your Understanding #1 – Burnout velocity of a single-stage rocket

Use the rocket equation to determine the burnout velocity and the maximum achievable height of a simple rocket, assuming that it is launched vertically. Neglect the aerodynamic drag forces. Solve for the burnout velocity and maximum altitude if the burnout time is 60 seconds. The specific impulse is 250 seconds, the initial mass is 12,700 kg, and the propellant mass is 8,610 kg. Assume the launch as vertical, ignoring curvature and drag, and solve for the required velocity, assuming it will be redirected to tangential velocity near apogee (e.g., by a circularization burn).

Show solution/hide solution.

The rocket equation gives the change in the velocity of the vehicle , i.e.,

where is the initial mass of the vehicle and

is the final or burnout mass. If gravity is included (but no aerodynamic drag), then

where is the burnout time, which is 60 seconds in this case.

The equivalent velocity is given in terms of the specific impulse, i.e.,

and the burnout mass is given by

The burnout velocity is given by the rocket equation, i.e.,

Therefore, at the burnout is

which is 2.19 km/s. Assuming the rate of propellant consumption is constant, then the mass of the rocket varies over time as

The velocity of the rocket is

The height achieved at the burnout time, , is

Inserting the values gives

Therefore, the height achieved is

The rocket’s final additional coasting height can then be determined by equating its kinetic energy at burnout with the change in potential energy between that point and the maximum height reached.

Launching into Orbit

Rocket launches are hugely exciting events to watch! The synchronized launch process, with its flaming exhaust and clouds of smoke, followed by the rising spacecraft into the sky, can be awe-inspiring. The technology and engineering behind the launches, the science and exploration they enable, and the thrill of human endeavor all contribute to the excitement. Additionally, watching a rocket launch live or on YouTube can be an educational and inspiring experience, especially for students and younger people interested in science and space. Even those who live in Florida never grow tired of watching rocket launches!

Using the Rocket Equation

Drama and excitement aside, the energy and propellant requirements for a rocket (booster) and its payload with the needed to reach a specific orbital altitude

can be estimated using the principles of energy conservation in conjunction with Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation. The rocket equation is given as

(31)

where is the equivalent exit velocity from the particular rocket engine,

is the initial mass of the rocket or spacecraft at the beginning of the burn, and

is the final (burnout) mass after the burn at burnout time,

, during which a propellant mass

is consumed. For simplicity, it is assumed that the vehicle is a single-stage vehicle (i.e., no staging).

The equivalent exit velocity can be written in terms of the specific impulse, , as

(32)

where is the reference value of acceleration under gravity at mean sea-level on Earth, i.e.,

m/s. Therefore, the rocket equation can also be written as

(33)

where the value of depends on the type of rocket engine and its propellant. If the value of

is known, then the rocket equation can be used to determine the propellant mass needed to give a certain

for the satellite or spacecraft to reach an orbit at the required altitude,

, as shown in the figure below.

For a launch, several factors can influence the required, i.e.,

- The needed orbital altitude above the surface of the Earth,

.

- The orbital inclination relative to the Earth’s equatorial plane.

- The launch latitude from the Earth (this affects the initial energy).

- The effects of overcoming gravity (when the rocket goes vertically).

- The aerodynamic drag on the rocket in the lower atmosphere.

- Steering losses because of small misalignments of the thrust vector.

Kinetic Energy

For the satellite or spacecraft to reach the required orbital altitude, , the

required for the needed kinetic energy is

(34)

noting that this result does not depend on the mass of the satellite or spacecraft. This latter component is the dominant energy requirement for high orbits.

Potential Energy

The associated with creating the needed potential energy for the same orbit is

(35)

For low orbital altitudes with , then

(36)

which is the dominant term in this case compared to the kinetic energy.

Gravity Loss Effect

A gravitational effect must be added to the total needed , usually called gravity loss. For a rocket going up vertically, then

(37)

where is the burnout time. If the rocket follows a curved trajectory and pitches over at a local trajectory angle

(with respect to the horizon) as it increases altitude, then

(38)

where when the rocket flies vertically and

when it flies horizontally. Therefore, properly evaluating this latter term requires information about the launch profile. Minimizing the gravity loss term means minimizing the burnout time.

Aerodynamic Loss Effect

There is aerodynamic drag on the rocket as it flies through the lower atmosphere, which contributes to the propellant required to reach a given . This drag force,

, can be expressed as

(39)

where is the dynamic pressure, i.e.,

where

is the local density of the air, and

is the true airspeed, the latter values also requiring information about the launch profile. An ISA model, applicable to the lower troposphere, stratosphere, and the extended upper atmosphere, can be used to represent air density. The reference area,

, in Eq. 39 is usually taken as the projected frontal area of the rocket. The drag coefficient,

, will also depend on the overall shape of the rocket and its flight Mach number.

The rocket’s drag given by Eq. 39 is proportional to air density and the square of the airspeed. This result indicates that to minimize the net aerodynamic effects, the rocket should ascend vertically but as slowly as possible; however, this is contrary to the need to accelerate the rocket as quickly as possible to minimize the cumulative gravitational effects on the net . Nevertheless, the aerodynamic loss on the achievable

is relatively small. More importantly, the dynamic pressure during launch requires particular emphasis, as it affects the aerodynamic-induced structural loads on the rocket. The value of

increases rapidly after launch, reaching a maximum and decreasing quickly as the altitude increases and the density of the air diminishes. In many cases, the “maximum

” value on the rocket will be limited, requiring the rocket engines to be temporarily throttled down to prevent excessive aerodynamic loads on the vehicle.

Aerodynamic drag coefficients for launch vehicles are not generally available. However, some research has been published, including Ballistic Research Laboratories, Memorandum Report No. 545, and NASA TM X-53770. The latter report presents the drag coefficients of the NASA Saturn V launch vehicle, as measured in several wind tunnels over a wide range of Mach numbers, with a sample shown in the figure below. The reference length used in the results is the diameter of the primary launch vehicle, where = 10.06 meters or 33 feet. The total drag (axial) force is split into forebody drag and base drag. Notice the rapid increase in drag coefficient during the transonic region near Mach = 1, followed by a progressive reduction in drag coefficient in the supersonic regime.

In the absence of any other information, the drag coefficient, , for a rocket is often represented as

(40)

where is the Mach number of the freestream aerodynamic flow. The

increment required to overcome aerodynamic drag (again, using the rocket equation) will be

(41)

where is the instantaneous mass of the rocket and

is the launch time over which aerodynamic forces are considered. However, for most launch vehicles, the

velocity losses from aerodynamic drag are cumulatively small and are typically between 0.05 and 0.15 km/s. For smaller rockets and air-to-air missiles that reach high flight speeds quickly, aerodynamic losses will likely need to be considered.

Launch Latitude

The required also depends on the launch latitude. The initial energy imparted to the rocket by Earth’s rotation is higher at launch sites closer to the equator. The needed

is lower if the rocket is launched in the direction of the Earth’s rotation (toward the east). For launches from Cape Canaveral, for example, the

boost (i.e., a negative

) is about 0.3 km/s and is certainly not insignificant regarding propellant requirements.

Total Delta-V

Therefore, the total needed is the sum

(42)

The required propellant mass, , can then be estimated from the rocket equation, i.e.,

(43)

again, assuming no staging. Therefore, using the principles of logarithms, then

(44)

If staging is used, the for each stage would be calculated as it is depleted of propellant, and the empty stage is discarded.

Estimating the Escape Velocity from Earth

The Earth’s mass, , is 5.97

kg. The radius of an initial orbit will be the radius of the Earth

, which is 6.3781

m, plus the orbital height,

. Also, we know that the universal gravitational constant

= 6.67428

N m

kg

. Assuming that the orbital height relative to the radius of the Earth is small, then it can be shown that the minimum escape velocity is given by

All spacecraft designed to head out into space away from the Earth must be given a velocity larger than 11.2 km/s, which is fast!

Steering a Rocket

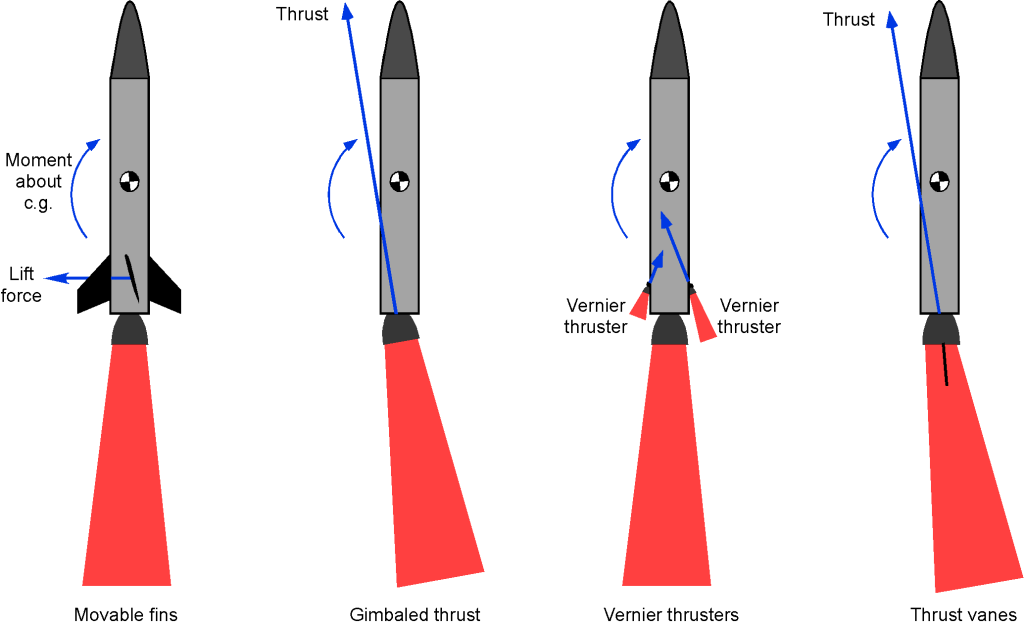

A rocket must be steered along a prescribed flight path to achieve the desired altitude and velocity. In modern launch vehicles, steering is accomplished primarily by gimbaling the main engine(s), which allows the thrust vector to be rotated slightly relative to the vehicle’s centerline. Tilting the thrust direction produces a torque that changes the rocket’s orientation and, hence, the direction of its flight path.

Historically, other techniques were also used. Early rockets and most air-to-air missiles employed movable aerodynamic fins to generate side forces and moments for steering. Some designs used small vernier engines for fine attitude control, or even thrust vanes inserted into the exhaust stream to deflect the jet. These systems have been replaced mainly by thrust vector control (TVC) due to its efficiency and mechanical simplicity.

Stability & Control

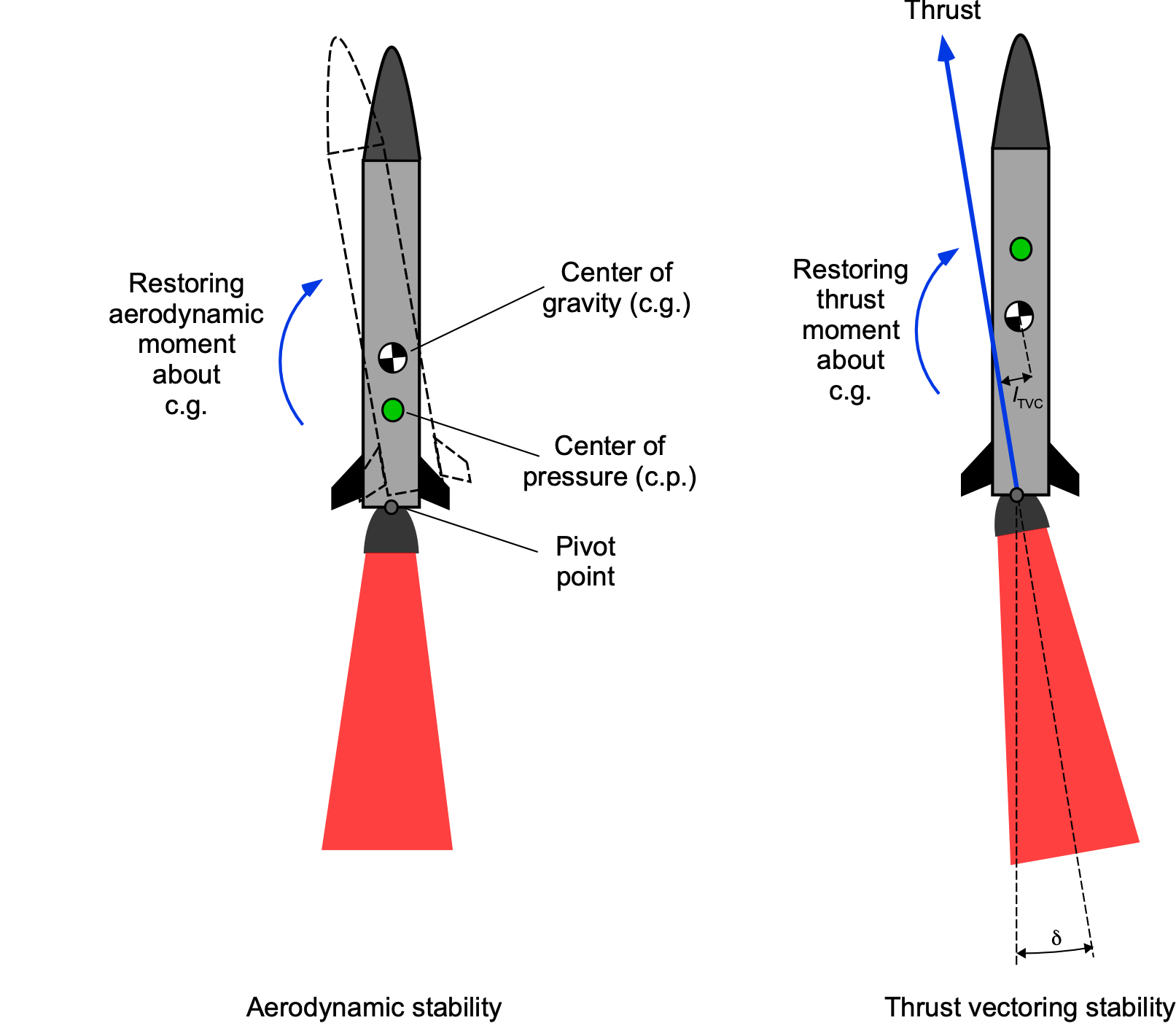

A rocket must also remain stably oriented so that the thrust direction follows the commanded flight path. At low altitudes, aerodynamic forces can help restore the vehicle’s alignment depending on where the center of pressure lies with respect to the center of gravity, i.e., for aerodynamic stability, then , which produces an aerodynamic restoring moment that tends to oppose disturbances, as shown in the figure below. However, as the propellant burns and the rocket gains altitude, the center of gravity and the center of pressure shift, which affects aerodynamic stability.

At subsonic velocities, the center of pressure is usually near the mid-body, about 50–60% of the length from the nose, but as the vehicle passes through transonic and into supersonic flight, the center of pressure shifts aft to about 80–90% of the body length, remaining near the fin plane until aerodynamic forces vanish in near-vacuum conditions. However, positive control can always be achieved primarily through thrust vectoring. Tilting the engine nozzle by a small angle generates a control moment

(45)

where is thrust and

is the lever arm between the nozzle pivot point and the center of gravity. Even deflections of one or two degrees are sufficient because the thrust is so large.

At high altitude or in a vacuum, reaction control jets provide the necessary forces and torques for attitude control. Because aerodynamic damping is usually relatively weak, every launch vehicle uses an automatic attitude control system. Gyros measure angular rates, and the controller commands tiny gimbal or thruster deflections to maintain pointing stability many times per second. The control system effectively supplies the stiffness and damping that the vehicle itself lacks.

Steering Losses

When a rocket changes direction, the thrust vector cannot remain perfectly aligned with the velocity vector. The component of thrust used to bend the trajectory does not contribute to increasing forward speed, leading to a small loss in total velocity capability known as the steering loss . The overall velocity increment provided by the propulsion system can be written as

(46)

where the various terms account for kinematic, upper-stage, gravity, drag, latitude, and steering effects. Steering losses are usually much smaller than gravity or drag losses, but can become noticeable when large trajectory turns are required.

Staged Rocket Vehicles

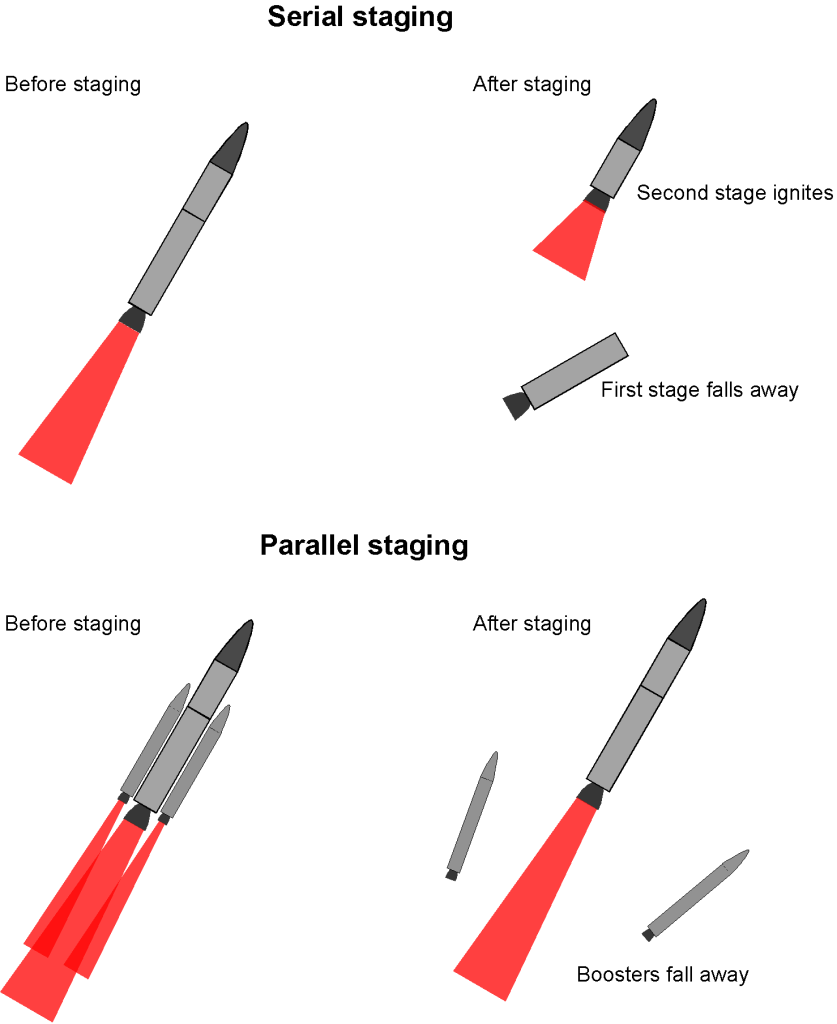

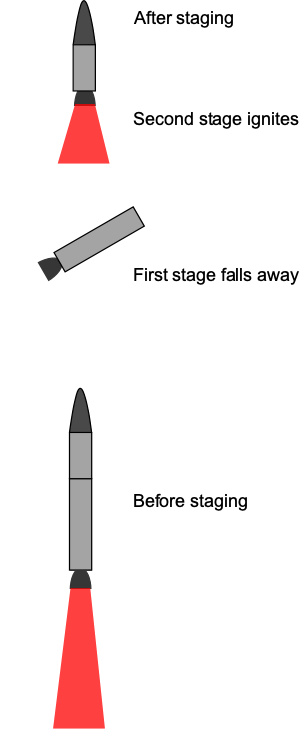

Staging a launch vehicle aims to maximize the payload ratio that can be launched into space. The goal is to launch the largest payload to the required burnout velocity with the least non-payload mass (defined as the rocket’s structural weight plus propellant). As shown in the figure below, there are two types of staging:

- Serial staging, where the stages are ignited, used, and jettisoned in serial sequence.

- Parallel staging, where all stages are ignited and used, but the stages are jettisoned as they burn out, e.g., solid rocket boosters.

To reach an optimal staging of the launch vehicle, there are four primary considerations:

- The initial stages should have the lowest values of

, and later stages should have the highest

.

- The stages with the lower

should contribute more to

.

- Each successive stage should be smaller than the previous stage.

- Similar stages should provide similar increments to

.

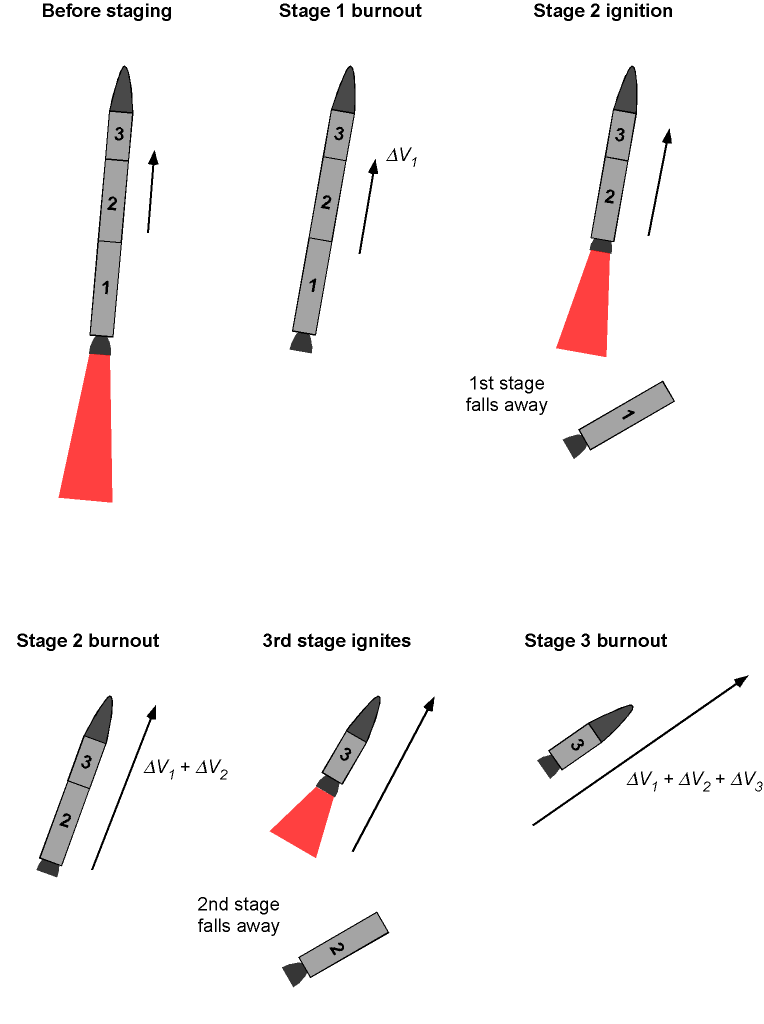

Serial Staged Rocket

For a serial staged launch vehicle, then

(47)

where the index refers to the stage number. Also

(48)

For a staged vehicle overall, the values are added for each stage, i.e.,

(49)

It can be assumed that this velocity is redirected as a tangential velocity for the payload to achieve an orbital path. The structural mass coefficients for a staged launch vehicle are usually similar to those of a single stage. However, payload ratios are generally higher for a staged vehicle. In some cases, determining the maximum allowable structural mass to meet specific payload requirements may be desirable, along with establishing certain structural design goals and constraints.

Below is a step-by-step breakdown of the general procedure for calculating the total burnout velocity or time for a multi-stage rocket with serial staging:

-

- Divide the rocket as a system into its stages. A specific propulsion system or engine typically characterizes each stage and will have its own parameters, such as mass, specific impulse, thrust, and propellant weight or burn time.

- For each stage, calculate the initial mass, which is the total mass of the rocket at the beginning of the stage burn, and the final mass, which is the rocket’s mass at the end of the stage burn after the propellant has been burned.

- Calculate the burnout velocity for each stage using the rocket equation. The gravitational effects acting on the rocket must also be taken into account.

- Add each stage’s burnout velocity to the previous stage’s initial velocity. Assuming that each stage occurs immediately after the previous one, the burnout velocity of one stage becomes the initial velocity for the next stage.

- Repeat steps 2–4 for the final stage of the rocket system until the burnout time and/or burnout velocity have been calculated for the final stage carrying the payload mass.

Check Your Understanding #2 – Two-stage rocket calculation

Consider a two-stage rocket with the following design characteristics. Payload mass = 60 kg. First stage: propellant mass = 7,200 kg, structural mass = 800 kg, and the mass flow rate is = 80.0 kg s

. Second stage: propellant mass = 5,400 kg, structural mass = 600 kg, and the burn time is 100 s. The specific impulse,

, for the first and second stages is 275 s. Assume the launch as vertical, ignoring curvature and drag, and solve for the required velocity, assuming it will be redirected to tangential velocity near apogee (e.g., by a circularization burn). Calculate the following:

For the first stage:

- The equivalent exhaust velocity.

- The thrust produced.

- The total burn time.

- The burnout velocity.

For the second stage:

- The equivalent exhaust velocity.

- The mass flow rate.

- The thrust produced.

- The final burnout velocity.

Show solution/hide solution.

For the first stage:

1. The equivalent exhaust velocity, , is

2. The thrust, , produced is

3. The total burn time, , is

4. The initial mass, , is

and inserting the values gives

The burnout mass, , is

and with the given values leads to the burnout mass of the first stage as

The increment for the first stage is

and inserting the values gives

Therefore, for the first stage, the burnout velocity is

For the second stage:

1. Because the remains the same for stage 2, the equivalent exhaust velocity will also be the same, i.e.,

2. The mass flow rate, , is

3. The thrust produced is

4. For the second stage, the initial mass is

The burnout mass for the second stage is

The for the second stage is

and inserting the values gives

The final value of the burnout velocity, , will be

Launch Height – Two-Stage Serial Rocket

Determining the burnout launch height, , obtained by a two-stage serial launcher, is obtained similarly to a single stage. In this case, the launch heights obtained by each respective stage are added, i.e.,

(50)

For the first stage, the height achieved at will be

(51)

and for the second stage, the height achieved at will be

(52)

Parallel Staged Launcher

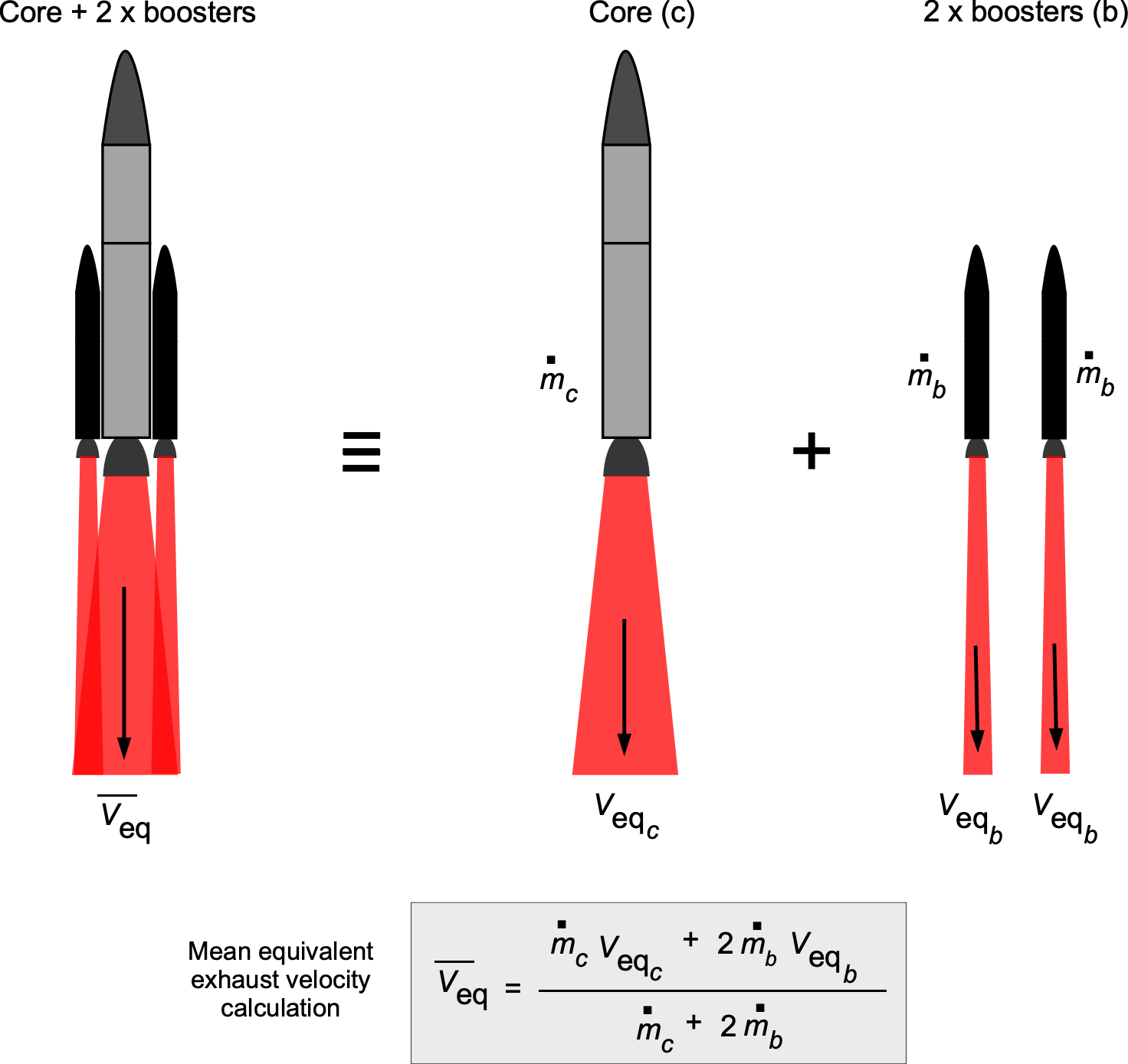

In a parallel-staged launch vehicle, there are usually dissimilar rockets and rocket engines burning simultaneously, as shown in the figure below. An example would be the NASA Space Shuttle, which used LH2/LOX for the “core” main engines on the Orbiter, with solid propellant rocket boosters being used to significantly augment the initial launch velocity. NASA’s SLS uses the same type of core and booster. Other launch vehicles may be configured with different numbers of solid rocket boosters, depending on the payload mass and desired orbital altitude. An exception is the SpaceX Falcon Heavy, which uses two additional liquid propellant boosters identical to the first (core) stage.

The rocket equation for a core rocket system with one or more boosters can be written as

(53)

where is the initial mass (core plus boosters) and

is the final mass of the launch vehicle after booster burnout. The average or mean equivalent exhaust velocity,

, is given by

(54)

where the subscripts and

refer to the core and the boosters, respectively. The value of

will be the boosters’ net mass flow rate. Alternatively, if

is the mass flow rate of any one identical booster (there is likely to be more than one booster), then

(55)

where is the number of boosters. An illustration of the process for a core rocket system with two boosters is shown in the figure below.

In this case, the initial mass at the launch point is

(56)

where and

are the propellant masses for the core and the boosters, respectively,

and

are the structural masses for the core and the boosters, respectively, and

is the payload mass.

Determining the final burnout mass, , of a launch vehicle with parallel boosters requires further consideration, as the core launcher will still have propellant left at booster burnout. Therefore, the final mass at the time of booster burnout, say

, can be written as

(57)

where is the fraction of propellant mass remaining in the core at booster burnout.

Notice that the mass of propellant, , used in a given time,

, is

, so the mean equivalent exhaust velocity,

, can also be written as

(58)

Therefore, the launch of parallel rocket stages can be presented using the sum of pseudo-serial stages, where for stage “0”, with the boosters and the core together, then

(59)

For stage “1” after booster separation, the initial mass will be

(60)

where is the fraction of propellant mass remaining in the core at booster burnout. The final mass after the stage 1 core burns out will be

(61)

where is the fraction of propellant mass remaining in the core at booster burnout.

Therefore, for stage 1, then

(62)

The values of the remaining stages,

, are then calculated as a serial launcher, as before, i.e., the final launch velocity

will be

(63)

Again, it can be assumed that this velocity is redirected as a tangential velocity, allowing the payload to achieve an orbital path.

Burnout Conditions for a Non-Vertical Launch

To place a payload into a stable circular orbit, a launch vehicle must impart sufficient energy to overcome gravity and atmospheric drag, and achieve both the correct altitude and velocity vector. In realistic scenarios, the trajectory is not vertical but gradually transitions from vertical to horizontal flight using what is known as a gravity turn, allowing the vehicle to align its velocity vector with the local horizon at burnout.

For a circular orbit at burnout, the vehicle must travel horizontally at velocity such that the gravitational acceleration provides the necessary centripetal acceleration, i.e., using the universal law of gravitation gives

(64)

where is the gravitational constant,

is the mass of Earth,

is the Earth’s radius, and

is the altitude at burnout. Solving for the required altitude gives

(65)

Notice that this relationship sets a geometric constraint in that orbital velocity and altitude are not independent.

The total velocity increment required from the launch vehicle must equal or exceed the orbital velocity from losses, i.e.,

(66)

In high-altitude ascent, aerodynamic drag is negligible, and steering losses can often be minimized. The dominant loss is from gravity, i.e.,

(67)

where is the pitch angle and

is the burn time. For an approximate analysis, then

(68)

where is the average value of

over the during the thrust phase or burnout time

. Substituting into Eq. 66 gives the approximate required velocity increment as

(69)

The achievable velocity increment is governed by the rocket equation, i.e.,

(70)

where is the effective exhaust velocity of stage

,

is the initial mass, and

is the burnout mass. For a two-stage vehicle, then

(71)

Equating this to Eq. 69 sets the design constraint for orbital insertion.

The altitude gained during thrust is computed by integrating the vertical velocity component, i.e.,

(72)

A simple estimate using average values gives

(73)

where and

are the average velocity and pitch angle, respectively, during

. This approximation captures the tradeoff between thrust direction and vertical altitude gain.

To design an ascent trajectory that leads to orbital insertion, one must determine the orbital altitude using Eq. 65, estimate gravity losses from Eq. 69, compute propulsion performance via Eq. 70, and confirm that the altitude and horizontal velocity at burnout are consistent with orbital conditions. This framework supports preliminary trajectory design, staging analysis, and mission feasibility studies.

Check Your Understanding #3 – Non-vertical launch

A two-stage launch vehicle is designed to place a 300 kg satellite into a circular low Earth orbit (LEO) at an altitude of 200 km. The first stage uses a propulsion system with a specific impulse of = 285 s, and the second stage has

= 326 s. The vehicle consists of a first stage with 8,000 kg of propellant and 80 = kg of structure, and a second stage with 2,500 kg of propellant and 250 kg of structure. The payload mass is 300 kg. Assume standard gravity

= 9.81 m/s2, negligible drag, and an average pitch profile such that

= 0.85. The total powered flight time is estimated to be

= 85 s. Determine whether the rocket can deliver the required velocity increment to achieve orbit, and calculate the burnout altitude.

Show solution/hide solution.

The orbital velocity required for a circular orbit at is computed from

(74)

Using the values m

/kg/s

,

kg,

m, and

m, the orbital radius is

m, then

The total required velocity increment is increased by gravity losses, i.e.,

(75)

Substituting values gives

To determine whether the rocket can deliver this velocity, we can use the rocket equation in terms of the specific impulse. The effective exhaust velocity for each stage is

The initial mass at launch is

For stage 1:

The second stage begins with

Therefore,

The total velocity increment delivered by the two stages is

which exceeds the required by approximately 135 m/s, providing a modest margin for steering corrections or minor unmodeled losses.

To estimate the burnout altitude, assume an average velocity magnitude 4,317 m/s. With

, the average vertical component is

. The burnout altitude is estimated as

Substituting the values gives

The rocket reaches a burnout altitude of approximately 183 km, close to the target orbit of 200 km. A brief circularization maneuver at apogee would complete orbital insertion.

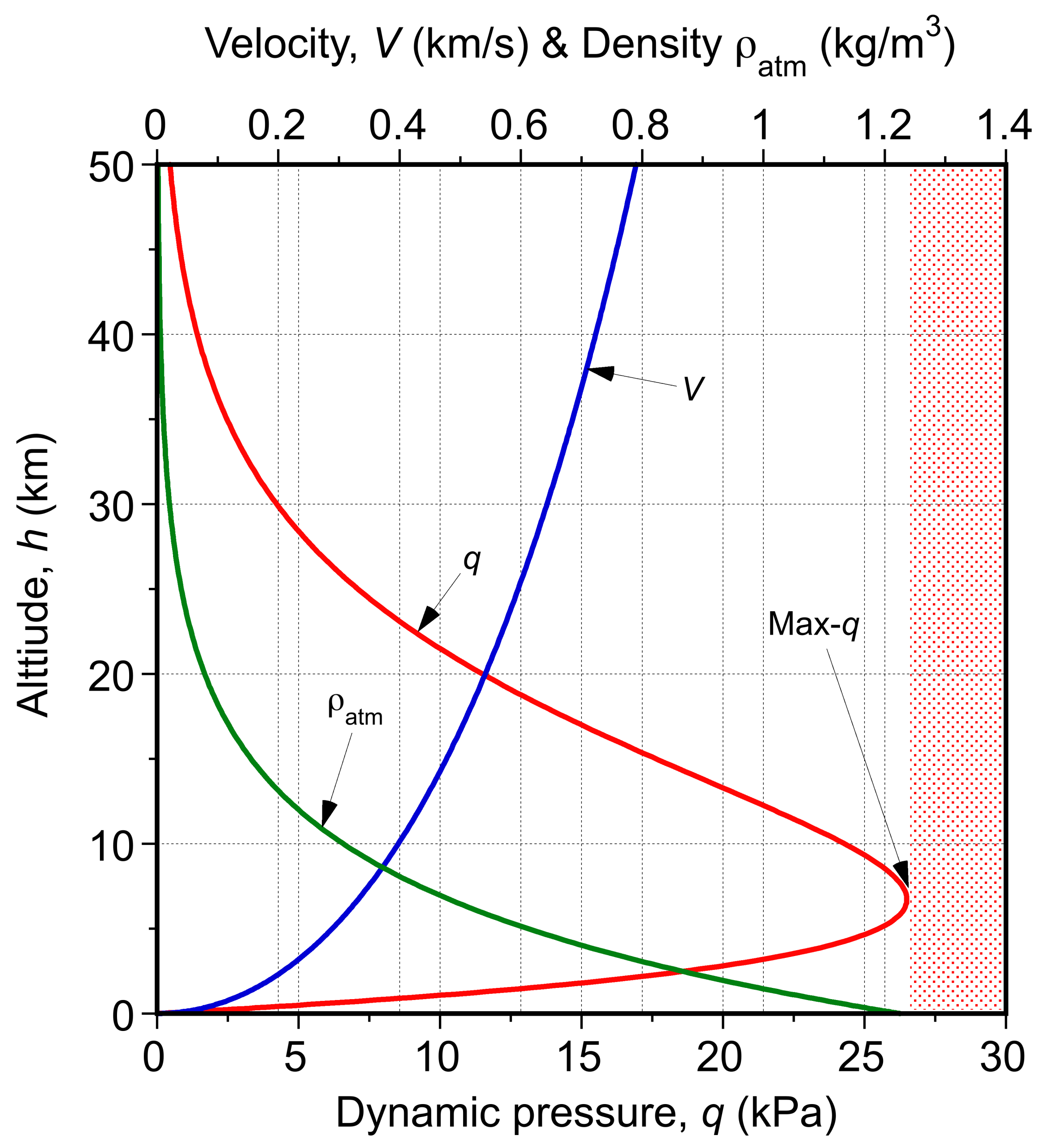

Maximum Dynamic Pressure (“Max-q ”)

During the ascent of a launch vehicle, the aerodynamic loads on the structure are determined by the dynamic pressure, i.e.,

(76)

where is the atmospheric density at altitude

, and

is the true flight velocity through the air. Immediately after liftoff, the vehicle is moving relatively slowly, so the dynamic pressure is small even though the air density is relatively high. At higher altitudes, the vehicle may be traveling at several kilometers per second, but the density is so low that \ (q \) is again small. Between these two extremes, there is an intermediate flight condition where the opposing trends of decreasing

and increasing

produce a maximum in

. This condition is referred to as the point of maximum dynamic pressure, or “max-

,” and it is a critical point in the launch envelope.

The velocity, altitude, and time at which the max- occurs can be determined by differentiating Eq. 76 with respect to time, which gives

(77)

Assuming the standard exponential atmosphere, then

(78)

where is the density scale height, which is usually taken as

7.2 km in the lower atmosphere. Substituting Eq. 78 into Eq. 77 gives

(79)

For a flight-path angle , the vertical velocity is

(80)

At the instant of maximum dynamic pressure, , so combining Eq. 79 and Eq. 80 gives

(81)

This result has a clear physical meaning: at max-, the acceleration along the trajectory,

, is exactly balanced by the rate at which the decreasing air density reduces the aerodynamic loading along the flight path. If

is greater than the right-hand side of Eq. 81, then

is still increasing; if it is smaller, then

has already begun to decrease. For a nearly vertical ascent, where

, the condition reduces to

. A shallower ascent, as in a gravity turn, delays the occurrence of max-

to a higher altitude and later time in the flight trajectory.

The engineering importance of max- is that it defines the point at which the vehicle and payload experience peak aerodynamic forces and moments. The structural design requirements for the launch vehicle are often driven by the loads that occur at this point. In addition to structural concerns, the product

, i.e., dynamic pressure times angle of attack, must remain below specified limits to prevent excessive lateral aerodynamic loading and structural bending. Guidance and control laws are therefore designed to schedule

appropriately. In most launch vehicles, the engines are throttled down in the seconds before max-

to limit the dynamic pressure to a predetermined safe value, and then throttled back up once the vehicle has climbed into the less dense air.

A representative medium-lift launch vehicle is shown in the figure below. Mmax- typically occurs about 60–80 s after liftoff, at an altitude of 11 to 15 km, when the velocity is approximately 0.4 to 0.55 km s

and the dynamic pressure reaches values of 25 to 40 kPa (about 3.6 to 5.8 psi). These values depend on the ascent profile and the vehicle’s thrust-to-weight ratio, but they provide a helpful reference.

Variable Thrust (Throttling) Conditions

The motion of a rocket with variable exhaust velocity and thrust can be analyzed by considering conservation of momentum. Neglecting external forces such as gravity and aerodynamic drag, the governing equation is

(82)

where is the instantaneous mass of the rocket,

is its velocity,

is the mass flow rate (negative), and

is the exhaust velocity, now assumed to vary as a function of mass. Rearranging the force balance gives

. Integrating from an initial mass

to a final mass

, and corresponding velocities

to

, gives

(83)

so that

(84)

This is a more general form of the rocket equation, in which the exhaust velocity depends on the propellant mass. If is constant, the classic form is recovered. Otherwise, the integral must be evaluated based on the specific functional dependence of

on

.

Suppose the rocket is throttled during flight, causing the exhaust velocity to vary with mass according to a power law of the form

(85)

where is the exhaust velocity at the initial mass

and

is a throttling exponent. Substituting into the integral gives

(86)

Evaluating the integral for gives

(87)

so that

(88)

If approaches zero, corresponding to no throttling and constant exhaust velocity, then the classic rocket equation is again recovered as the limiting case. Using a Taylor expansion,

(89)

so that

(90)

This result shows that throttling, by varying the exhaust velocity during the burn, modifies the usual logarithmic dependence of on the mass ratio. Throttling down, such as at the conditions of maximum dynamic pressure, corresponds to small positive values of

. In practice, throttling the rocket engine slightly reduces the achievable

compared to the ideal constant-exhaust-velocity case.

Missiles & Ballistics

Ballistic trajectories refer to the paths that missiles or artillery projectiles follow from their launch point to their intended targets. Predicting these trajectories is crucial in determining the missile’s flight path, range, and target accuracy. Missile trajectories can vary significantly depending on the type of missile, its intended purpose, the required range, the altitude at which it flies, and the guidance system it employs.

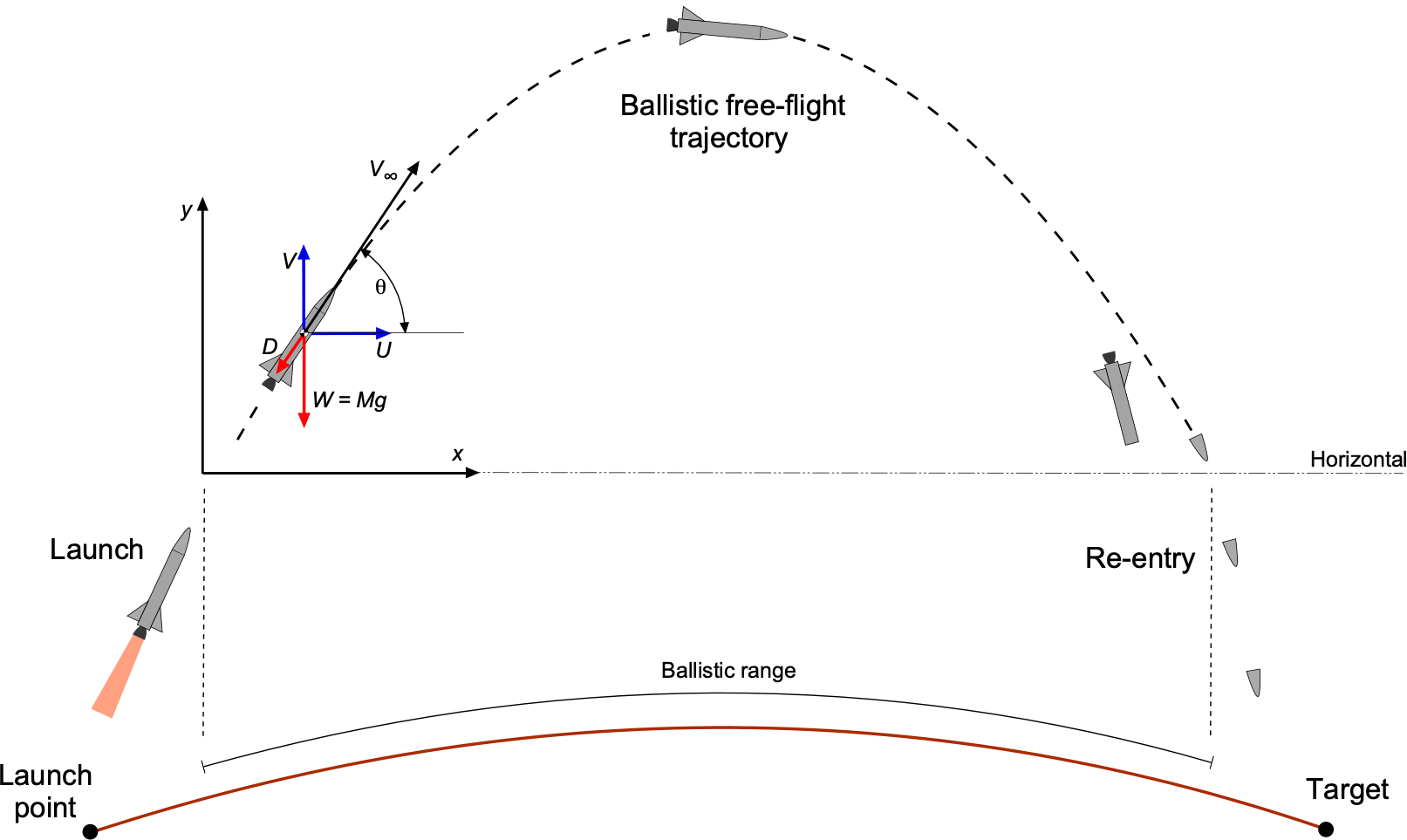

Ballistic missiles follow a trajectory primarily influenced by gravity and the initial launch conditions. They are launched into the atmosphere either vertically or at a steep angle. They then follow a parabolic or elliptical path well into the stratosphere or the edges of space, eventually re-entering the lower atmosphere and impacting their target. Ballistic missiles are known for their high speed and relatively long-range targeting capabilities.

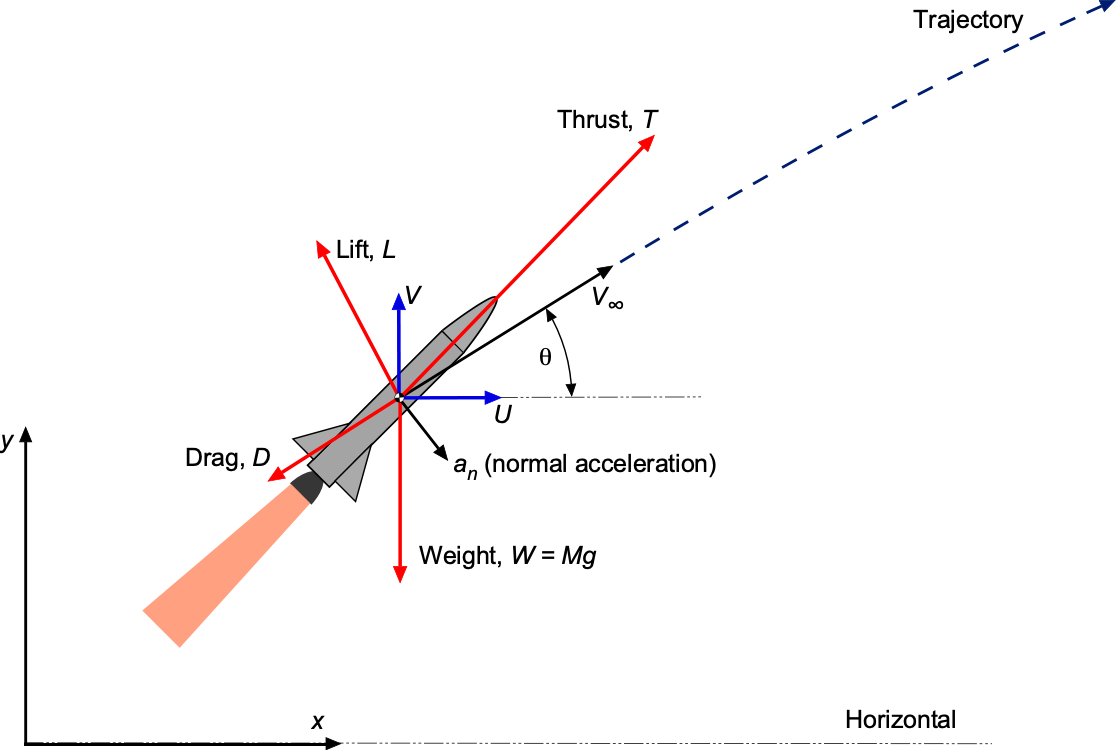

Consider the equations of motion of a missile, as shown in the figure below. For the direction parallel to the flight path, then

(91)

where is the mass of the missile acting at its center of gravity, and

is its acceleration in the direction of the flight path.

Similarly, the equation of motion perpendicular to the flight path is

(92)

where is the distance along the flight path, i.e.,

, where

is the instantaneous radius of curvature of the flight trajectory. The second equation of motion is then

(93)

In principle, Eqs. 91 and 93 can be solved to predict the launch trajectory of the missile, much in the manner considered previously using the rocket equation. However, the process is much more complicated than this and requires several more assumptions and approximations to obtain any useful results. Likewise, with the re-entry trajectory, there are many variables to consider, not just limited to simple dynamics and aerodynamics.

In the following more elementary exposition, assume that after the initial launch to high altitude, the rocket engine cuts off so that the thrust, , is zero, as shown in the figure below. Also, assume that

, so there is no aerodynamic lift.

The equations of motion now become

(94)

The aerodynamic drag on the missile is given by the standard formula that

(95)

where the drag coefficient, , is based on the reference area,

, which, by convention, is usually the maximum cross-sectional area of the missile. Let the aerodynamic drag be expressed in the form

(96)

where

(97)

where the mean value comprises an average of the aerodynamic drag over the ballistic trajectory. Therefore,

(98)

However,

(99)

so that

(100)

Letting , which seems a reasonable assumption, especially for a long-range ballistic missile, gives

(101)

Separating the variables and integrating them gives

(102)

This equation has a solution

(103)

where is the value of

at

. Therefore,

(104)

(105)

Consider now the equation of motion in the -direction, which becomes

(106)

Therefore,

(107)

and so

(108)

Integrating the preceding equation gives

(109)

noticing that at

. By dividing both sides of the foregoing equation by

, then

(110)

(111)

Therefore, Eqs. 105 and 111 will give the approximate position of the missile’s trajectory in terms of time, .

When the aerodynamic drag is small, i.e., the ballistic trajectory is mostly in the higher atmosphere or in space, then and the equations of motion reduce to

(112)

as well as

(113)

where is the initial velocity. These are the classic equations for the parabolic trajectory of any unpowered projectile, such as an artillery shell.

It can be shown that the total flight time, , of the missile or projectile for level ground, i.e., assuming the launch point and target are at the same height,

, is given by

(114)

where is the initial launch angle of elevation of the projectile. The corresponding range,

, is

(115)

The maximum range occurs when = 45

, i,e.,

.

These preceding equations, collectively, are sometimes referred to as the Laws of Ballistics or the Artilleryman’s Range Equations. However, if the variation of is accounted for during high-altitude flight using the inverse-square law of gravitational attraction, then the trajectory will be elliptic. The effect would be to increase the range of a high-altitude projectile slightly.

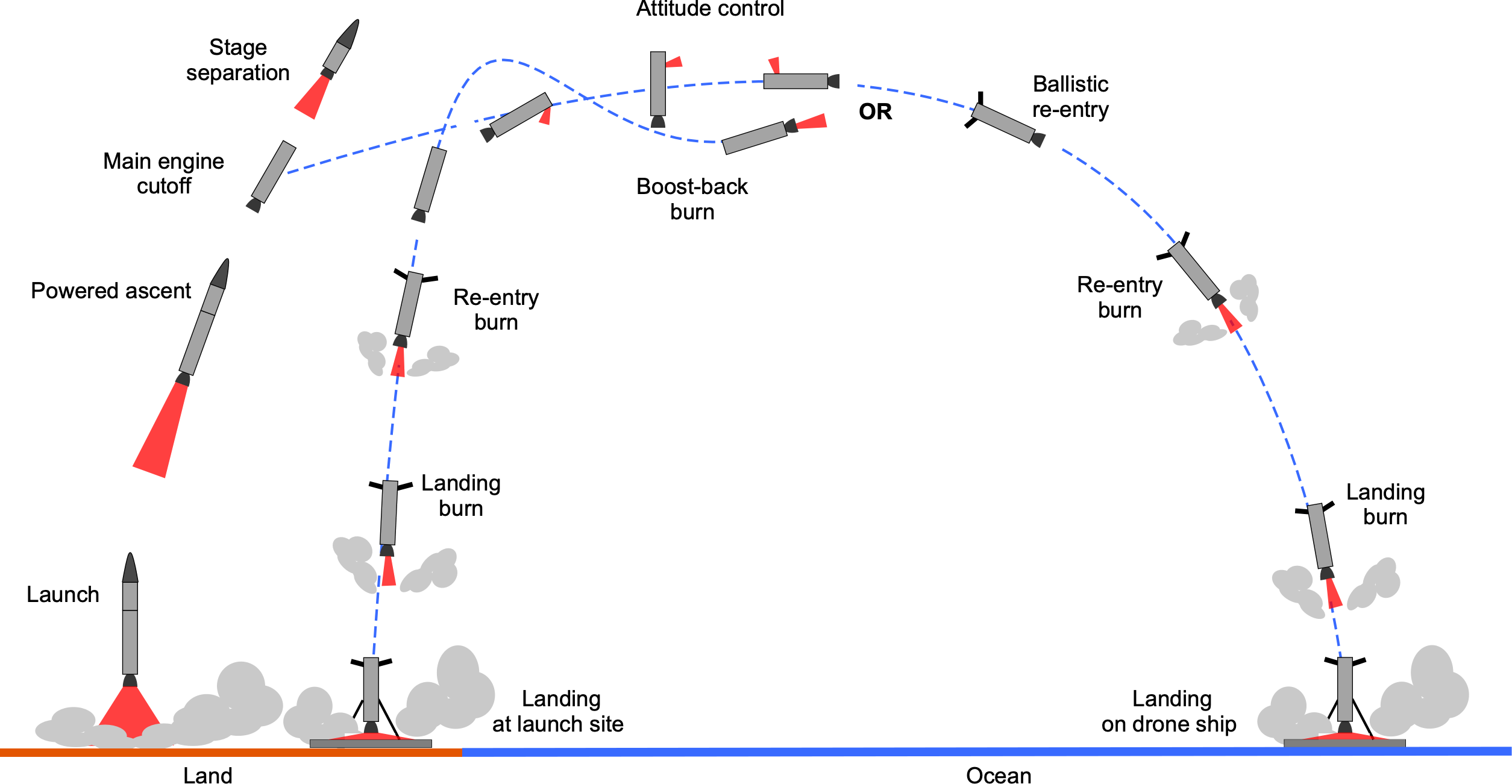

Falcon 9 Booster Re-entry

Reusable launch vehicles are revolutionizing space flight and reducing the cost of sending a payload into orbit. The James Bond film You Only Live Twice, which was released in 1967, introduced the concept of a reusable rocket in popular culture, depicting a spacecraft launched into orbit by SPECTRE, completing its mission of capturing another spacecraft, and returning to Earth for reuse. Though fictional at the time, the concept became a reality with the Space Shuttle and is now being further advanced by companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin.

Falcon 9’s first-stage booster recovery is a remarkable engineering achievement, combining an advanced knowledge of aerothermodynamics, flight dynamics, and guidance and control into a single, integrated system. The process begins with a drag-governed ballistic entry, using aerodynamic forces to dissipate most of the booster’s potential and kinetic energy. This is followed by two retro-burns of the rocket motors and a precisely timed landing maneuver. Guidance algorithms continuously update the flight trajectory based on real-time values of velocity, altitude, and atmospheric conditions. The goals in achieving a successful booster recovery are:

-

- Accurately predict and control the descent trajectory so the recovered booster arrives at the landing site on the correct flight path, velocity, and attitude.

- Determine the optimum amount of propellant required for each burn (boost-back, re-entry, landing) to ensure a safe, precise touchdown within the available propellant mass budget.

- Manage the flight path of the booster to minimize kinetic heating and the associated thermal loads.

While predicting the details of the optimal re-entry and recovery trajectory requires numerical solutions of the equations of motion with a realistic atmospheric model (e.g., the exponential model or the piecewise atmospheric model for from the troposphere to the thermosphere), the sequence of steps can be described analytically to illustrate the key principles.

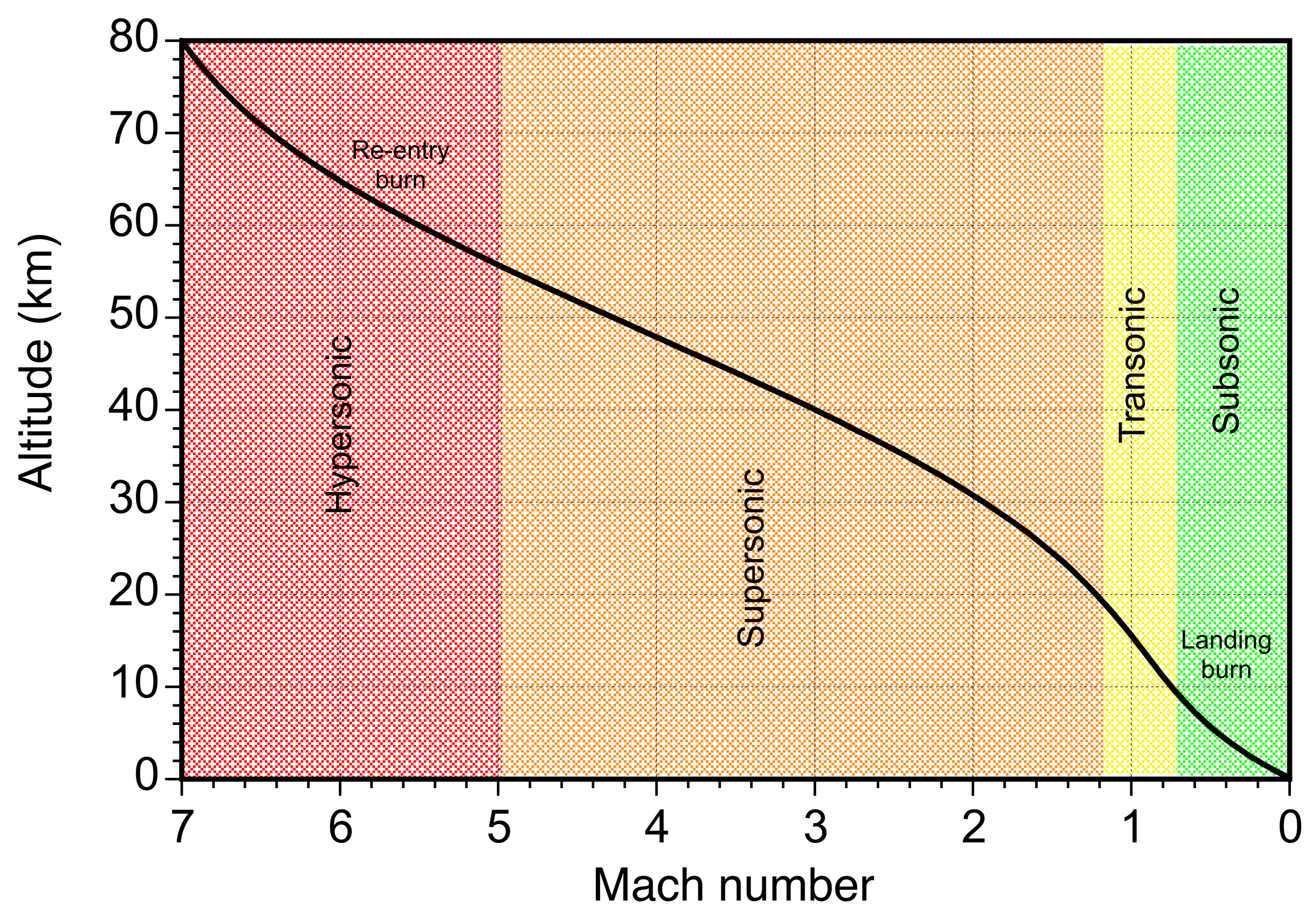

Stage Separation

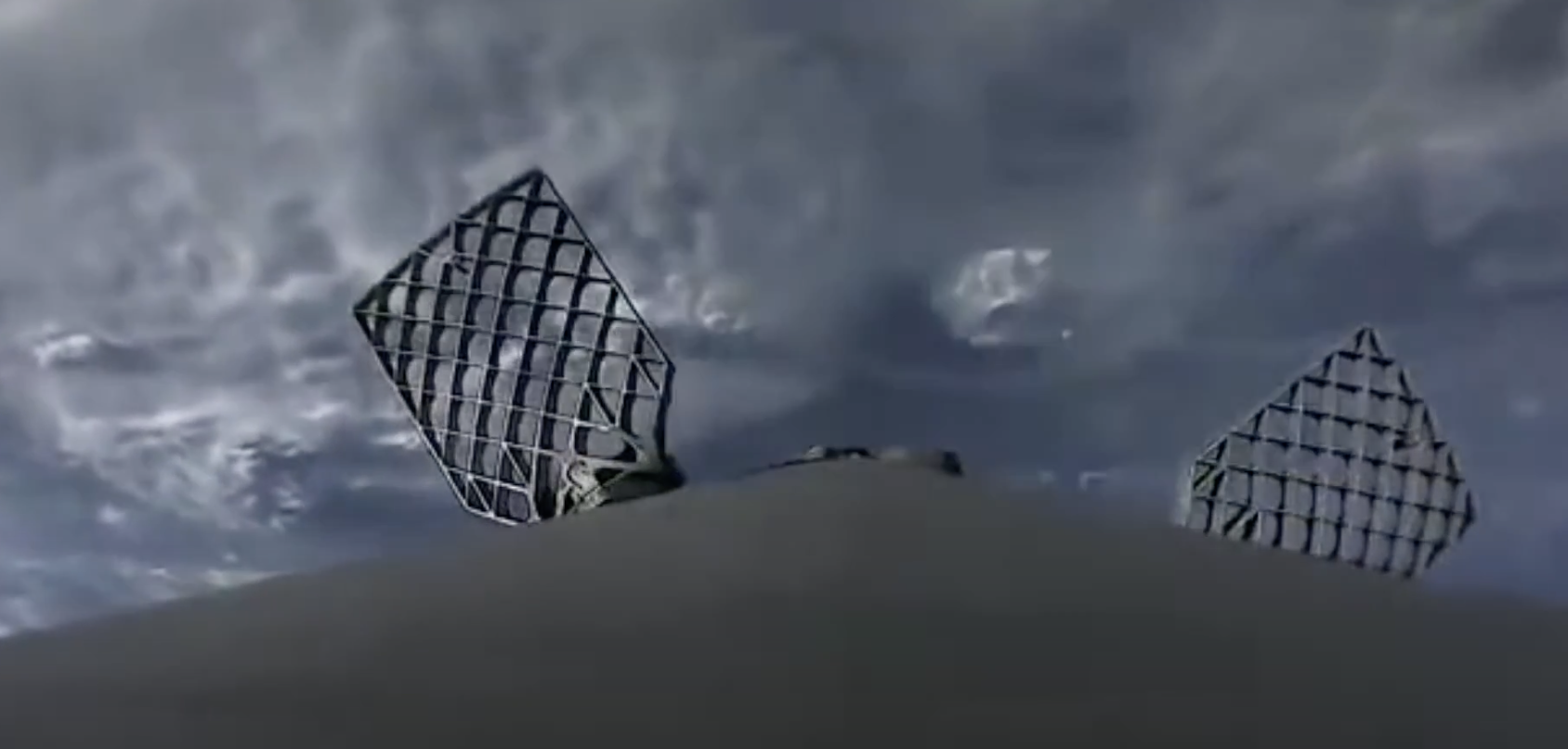

After stage separation at an altitude of about 70 km and a velocity of about 8,000 km/h (about 2,220 m/s, which is in the Mach 6–8 hypersonic regime at this altitude), the booster continues on an upward ballistic trajectory to an apogee of about 120 km at a velocity of 7,000 km/h (1,944 m/s). Then it begins its return to Earth in an engines-first orientation, as shown in the figure below. Cold gas thrusters, which are small nitrogen attitude control jets, manage the orientation of the booster and prevent it from tumbling during the high-altitude, low dynamic-pressure portion of re-entry.

The grid fins are also deployed (except during a boost-back maneuver), which helps with aerodynamic braking and control. However, the density is so low at altitudes over 100 km that drag does not become significant until the vehicle drops below about 80 km. The booster exhibits passive tail-first directional stability. As the aerodynamic center of pressure shifts toward the top (now the tail) of the booster and the center of mass moves toward the base (now the nose) as a result of the empty propellant tanks, this results in a form of pendular stability. It also places the nine Merlin engines into the oncoming flow, creating a high-drag configuration that enables rapid deceleration and significantly slows the booster before it reaches the denser lower atmosphere. The engines and propulsion hardware, along with the surrounding base heat shield, are designed to withstand the kinetic heating during reentry.

The overall descent of the booster follows a nominally ballistic trajectory, governed by gravity and aerodynamic forces, and interrupted only by brief periods of thrust from the boost-back burn (if used) and the re-entry burn. In the initial ballistic phase, the deceleration of the booster can be represented by the sum of gravity and aerodynamic terms, i.e., according to the principles of ballistics, the equation of motion for the booster is approximately

The equation of motion can be approximated by

(116)

where is its velocity,

is the initial mass of the booster at first-stage burnout, and

is the atmospheric density profile for a given height

. In addition,

is the base area of the booster and

is the area of the grid-fins.

is the drag coefficient of the booster in the tail-first flight orientation, which is typically in the range

to

for cylindrical-like bluff bodies. The drag coefficient,

, of the grid-fins is more complex to model and is considered next. For sub-orbital heights, as in this case, it is usually assumed that

.

The booster has both horizontal velocity and vertical (downward) velocity

, so the total relative flow velocity is

. Splitting into horizontal (

) and height (

) components gives

(117)

with the kinematic relations and

, noting that the

velocity, and hence the downrange distance, is affected by the amount of aerodynamic drag. These ODEs are then numerically solved to estimate the flight trajectory. When the booster is in flight, guidance algorithms continuously update the required trajectory to follow the estimated trajectory. In trajectory prediction, calculating the ballistic coefficient is a useful cross-check of how quickly the booster will decelerate, i.e., using

(118)

with lower values producing faster deceleration and with kinetic heating. Immediately after separation, the stage enters the hypersonic regime, where aerodynamic heating rates are high but the dynamic pressure and aerodynamic drag remain relatively low.

Boost-Back Burn

The boost-back burn maneuver, if performed, alters the landing point from a downrange drone ship to a pad near the launch site by reversing the booster’s horizontal velocity after launch, thereby imparting a component opposite to that of the typical ballistic trajectory. After stage separation, which occurs at a velocity of about 6,000 km/h (approximately 1.67 km/s), the booster is commanded to perform a backflip maneuver. A burn follows, which significantly reduces its downrange velocity and distance. The grid-fins are not deployed during a boost-back maneuver. During the burn, the vehicle continues to coast upward on a ballistic trajectory, reaching a peak altitude (apogee) of about 150 km at a velocity of roughly 1,000 km/h (0.28 km/s). Some of the booster’s initial kinetic energy is converted into gravitational potential energy, which is why its altitude increases even as its velocity decreases.

From an energy perspective, the booster initially possesses mechanical energy per unit mass given by

(119)

where and

are the horizontal and vertical velocity components, respectively, and

is the nominal altitude at stage separation. The boost-back burn imparts a velocity change

, which reduces the horizontal velocity and may increase the vertical velocity if the thrust vector is pitched upward. Therefore,

(120)

Treating the burn as impulsive and neglecting aerodynamic drag, the change in specific kinetic energy across the burn is

(121)

so that

(122)

Recognizing that , then

(123)

The post-burn mechanical energy per unit mass is

(124)

and during the subsequent ballistic coast (no thrust, drag neglected), energy is conserved, so remains constant as some kinetic energy is converted into gravitational potential energy. A reduction in

from

to

, combined with an increase in

, can raise the apogee even as the total velocity decreases.

This boost-back maneuver requires a significant additional mass of propellant, reducing the propellant available for the launch and, therefore, lowering the maximum payload mass to orbit compared with a downrange drone-ship recovery. The required velocity change in the burn to follow the required trajectory can be estimated from the rocket equation using

(125)

where is the booster’s mass immediately before the burn and

is the mass of propellant needed for the burn, i.e.,

(126)

Grid-Fins

The four deployable grid-fins (which are not a SpaceX invention) mounted near the top of the booster, as shown in the photograph below, provide both aerodynamic drag (i.e., braking) and control during the supersonic, transonic, and subsonic phases of descent. When deployed, the booster flies with its engines at the front, so the fins are positioned at the top of the booster (now its tail), where they provide directional stability and drag. In this respect, they function like a steerable parachute, generating both stabilizing and controllable aerodynamic forces.

Grid-fins have relatively high drag coefficients when they are placed normal to the flow, typically in the range of about = 0.6–0.8 at subsonic speeds, rising to 0.8–1.5 in the transonic and supersonic regimes. At a local flow angle

, set by the vehicle attitude, and with a commanded fin deflection

, the effective angle of attack is

(127)

where is the control-effectiveness factor, i.e., in the manner used for a flap or any other aerodynamic control surface. A canonical drag coefficient model for a grid-fin is

(128)

where is the minimum drag coefficient, typically about 0.2, and

is an empirical constant that represents the behavior of a particular grid-fin design. Notice that the

dependence in the grid-fin drag model arises from the combination of two effects; the projected frontal area of the fin to the freestream grows approximately as

, while the perpendicular dynamic pressure scales as

. Multiplying these effects then gives a cubic dependence on angle of attack.

Therefore, the equation of motion becomes

(129)

where with the boost-back burn or

without it.

The orientation of each grid-fin can be separately controlled to provide precise steering, allowing the stage to be placed on the exact flight trajectory needed for landing. The resulting aerodynamic forces and moments, combined with reaction control thrusters in the near-vacuum upper portion of the trajectory, maintain the booster’s correct attitude for a well-controlled descent profile.

Re-Entry Burn

Between the boost-back burn (if performed) and the re-entry burn, the descent remains predominantly ballistic. The re-entry burn is performed at approximately 60 km and at a velocity of between 5,000 km/h and 7,000 km/h (1.39 km/s to 1.94 km/s, or at a Mach number between 4 and 6), as shown in the flight profile below. This burn reduces the velocity by 3,000 km/h (0.83 km/s). Only three of the nine Falcon rocket motors are used for this burn. The required propellant mass for the burn can be estimated from the rocket equation using

(130)

where is the booster’s mass immediately before the burn and

is the propellant mass required, i.e.,

(131)

The mass of the booster after the re-entry burn is now when including the boost-back burn, or

without the boost-back burn.

As the booster stage descends into denser air, it progressively decelerates through the supersonic regime, where the peak dynamic pressure usually occurs at an altitude of around 15 km and a velocity of 3,000 km/h (Mach 2–3). Because the dynamic pressure is and the kinetic heating rate scales as

, even a modest velocity reduction has a significant effect on the structural and thermal loads. Heating is most severe across the entire engine section, including the nozzles, support structures, the surrounding base heat shield, and the grid fins that project into the flow. Early Falcon 9 flights used aluminum grid fins, but these were later replaced with cast-titanium fins to withstand higher re-entry temperatures.

Landing-Burn

While still supersonic, the bow and tail shockwaves extend to the ground as sonic booms, which can be heard over considerable distances downrange from the flight path. As the vehicle passes through transonic conditions, rapid, nonlinear changes in aerodynamic coefficients occur, and shock waves move across the grid-fins, requiring careful control of the booster’s trajectory. Below Mach 0.8, the flow is fully subsonic, and the booster, which is now slowing down quickly in the thicker lower atmosphere, is stabilized for the start of the landing burn. The landing burn, which uses a single engine, commences at an altitude of approximately 2.5 km when the booster is traveling at about 900 km/h (0.25 km/s). In the final seconds of descent, the landing burn negates the remaining velocity of the booster, i.e., using the rocket equation gives

(132)

where is the booster’s mass immediately before the burn and

is the propellant mass required for the landing burn, i.e.,

(133)

Therefore, the total propellant mass required for recovering the booster is

(134)

including the boost-back maneuver, if one is used. The booster, just about to touch down, is shown in the photograph below.

The timing of the landing burn is critical. Starting too early wastes propellant and can result in a hover above the landing pad, while starting too late risks a hard landing. A “hover-slam” profile is therefore flown, in which the booster touches down with a small rate of descent and the engines shut down at the instant of touchdown. As of 2025, SpaceX has performed booster landings over 500 times.

Summary & Closure

Payloads launched into space encompass a wide range of missions, including communication satellites, weather satellites, scientific instruments, crewed spacecraft, and planetary exploration probes. Payload mass and size are critical considerations in the design and selection of a launch vehicle. Heavier payloads and missions requiring higher orbital altitudes require larger, more powerful rockets capable of delivering greater energy. Missions to low Earth orbit (LEO), such as those involving Earth observation or communication satellites, require less total energy than missions to geostationary orbit or interplanetary destinations. Launch vehicle configurations are carefully tailored to meet mission requirements, optimizing performance and minimizing costs.

Understanding launch vehicle performance requires an appreciation of the fundamental principles governing rocket flight. The rocket equation describes the ideal velocity increment achievable by a rocket, i.e.,

where and

are the initial and final masses, and

is the equivalent exhaust velocity. However, actual missions require a greater

than the ideal value because of losses associated with gravity, aerodynamic drag, and steering. Gravity losses, which typically amount to 1.5 to 2.5 km/s, arise from the continuous downward pull of Earth’s gravitational field during ascent. Drag losses, associated with aerodynamic resistance in the atmosphere, typically contribute 0.1-0.3 km/s. Steering losses, incurred when the rocket’s thrust vector is not perfectly aligned with its velocity vector, typically range from 0.1 to 0.5 km/s.

Because of the inherent limitations of carrying all propellant in a single stage, launch vehicles often employ multiple stages. Staging allows the vehicle to discard empty structural mass and engines, improving the effective mass ratio and making orbit more attainable. The performance of each stage depends critically on its propellant mass fraction, i.e., the fraction of its initial mass that is usable propellant, and structural mass fraction, i.e., the fraction dedicated to tanks, engines, and support systems.

The efficiency of a rocket engine is characterized by its specific impulse, , which relates directly to the exhaust velocity through the expression

where is the standard gravitational acceleration. Higher values of

enable rockets to achieve a given

with less propellant, increasing mission efficiency. Launch trajectories are carefully shaped to optimize energy use. Rockets perform a gravity turn shortly after liftoff, arcing over gradually to build horizontal velocity while minimizing steering losses.

Commercial companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin have contributed to the development of new rocket technologies, including reusable launch vehicles and commercially operated crewed spacecraft. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft, for example, provides transportation to and from the International Space Station under contract with governmental agencies. Commercial satellite launches for communications, navigation, and Earth observation have also become an established sector of the space industry. Additionally, there is active development of human spaceflight for non-governmental purposes, including space tourism initiatives.

5-Question Self-Assessment Quickquiz

For Further Thought or Discussion

- Consider a staged vehicle for which all

values are the same. How can

be maximized?

- How does a rocket navigate and change its course during flight?

- What is the role of aerodynamics in rocket design?

- How do scientists and engineers calculate the optimal launch trajectory for a rocket?

- What are the challenges of reusing rockets, and why is rocket reusability important?

- Can you name some famous rockets and their notable achievements?

- How has rocket technology evolved, and what are the prospects for rocketry?

Other Useful Online Resources

To learn more about rockets, launch vehicles, and other spacecraft, check out these helpful online resources:

- An article on the history of rockets by NASA

- Great video: The Evolution of Space Rockets.

- The U.S.’s first person in space, Alan Shepard, launches on a Mercury Redstone rocket.

- Saturn V: The rocket that took humans to the Moon – The Saturn V Story.

- Experience the flight of Apollo 11.

- STS-134 – The final launch of the Space Shuttle Endeavour.

- Artemis I Launch to the Moon – Official NASA Broadcast – Nov. 16, 2022.

- First test flight of the SpaceX Falcon Heavy.

- SpaceX Falcon Heavy launches the NASA Psyche – see video here.

- SpaceX Starship SN10 launch and landing – see video here.

- Blastoff! Blue Origin launches 33 payloads.

- Scott Manley’s excellent YouTube channel on everything to do with spaceflight!