44 Aircraft Propellers

Introduction

The modern propeller stands as a testament to the achievements of aeronautical engineering. Since the earliest days of flight, propellers have been the focus of continuous refinements and technological advancements, further shaping the evolution of aircraft designs. Today, companies such as Hartzell, Sensenich, and McCauley produce highly efficient, advanced propellers made of composite materials, aerodynamically optimized airfoil sections, and sophisticated blade geometries with swept leading edges to minimize compressibility effects. These modern designs, exemplified by the photograph below, reflect more than a century of progress in aerodynamics, materials science, and manufacturing techniques, closely paralleling and often driving broader innovations in aviation.

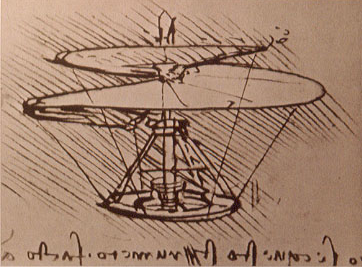

The earliest known use of propellers or rotors dates back to around 500 BC in ancient China, where children played with bamboo dragonflies. These were simple wooden toys consisting of a stick and blades that, when spun rapidly between the hands, would lift into the air. Leonardo da Vinci, in the 1480s, sketched the “aerial screw,” as shown in the figure below. This concept was an aerodynamic device derived from an Archimedes water screw, which some consider a precursor to the modern helicopter rotor. Although never built at its intended human-carrying scale,[1] Da Vinci’s design laid down the concept of using rotating wings to create an aerodynamic force parallel to their axis of rotation, a force called thrust.

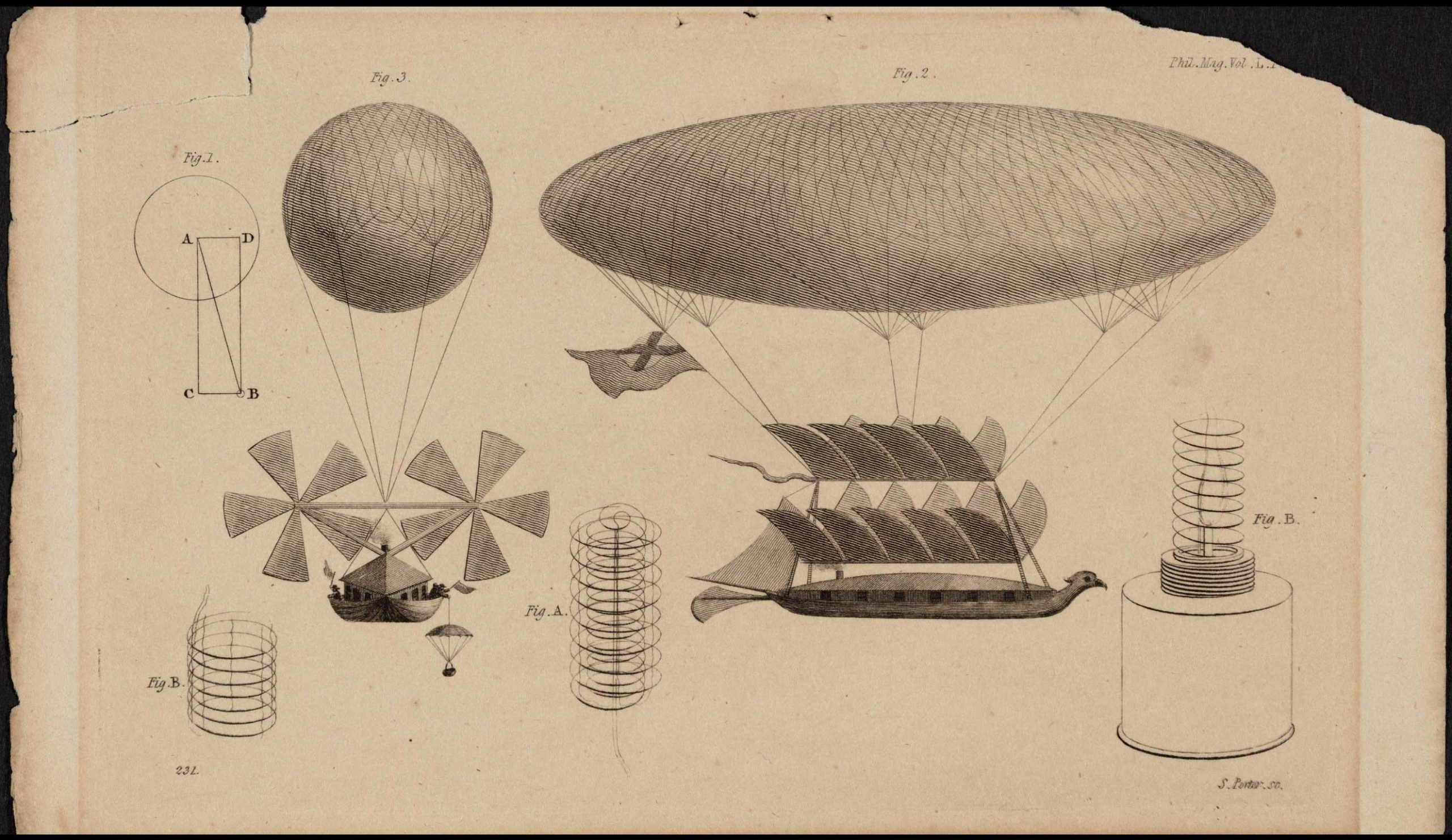

In the 19th century, George Cayley made significant contributions to understanding the principles of flight, experimenting with gliders and recognizing the need for a powerplant and propulsion mechanism if sustained flight was ever to be achieved. At least one of his airplane concepts and an airship, the latter shown in the illustration below, indicated that the means of propulsion was using “airscrews” or propellers. The power source was not specified, although the only option at the time would have been a steam engine.[2] The use of “screw” propellers for propulsion was nothing new, having been used in marine applications since the 1830s. Still, the propeller blade designs suitable for good efficiency in the air had yet to be determined. In the 1870s, Thomas Moy built the Aerial Steamer, an early powered aircraft with two, six-bladed propellers driven by a steam engine. The blades had geometric twist, their pitch becoming finer at the blade tips. Like the Cayley concept, however, although it did not fly, it was a step forward in critical thinking about how an airplane might be propelled.

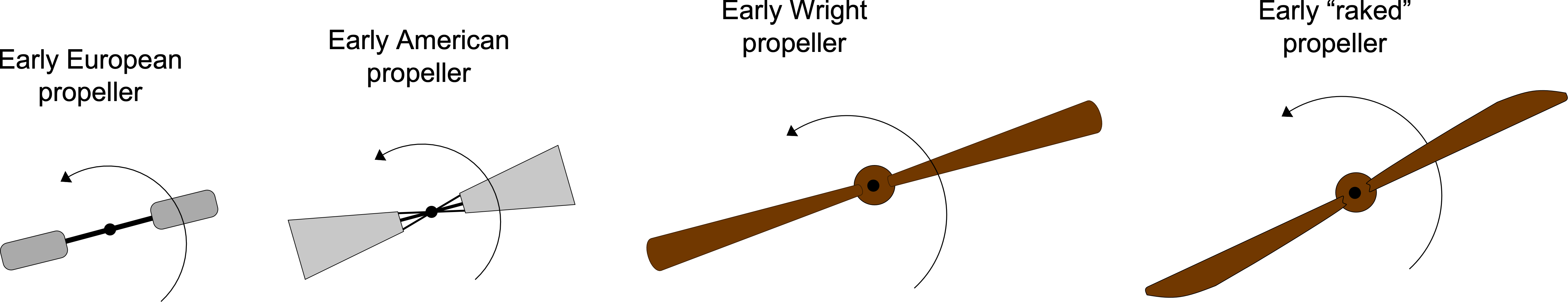

In 1903, the Wright brothers made the first successful, powered flight with their Wright Flyer, equipped with twin wooden propellers designed and built in their workshop. The Wrights discovered that there was no theory or other analysis to describe or predict propeller performance. The state of the art at the time was simply trial and error. They then set out to study the aerodynamics of propellers in a wind tunnel of their own design, demonstrating that long, thin (i.e., high-aspect-ratio) blades with nose-down twist (called washout) along their span yielded the best propulsive efficiency. By 1908, they had improved their propeller designs for the Wright Flyer III, enabling flights of much longer duration and range. Their “raked” propeller had a swept leading edge and more blade area toward the tip, as shown in the figure below. This design gave further efficiency improvements, allowing more of the limited engine power to be converted into thrust. The broader propeller tips were also structurally stiffer, preventing them from buzzing and fluttering, a shortcoming of many early propeller designs.

During WWI, propeller technology advanced rapidly to meet the demand for airplanes with greater performance. Initially, fixed-pitch wooden propellers carved from laminated spruce blocks were standard, as shown in the photograph below. However, as engine power and aircraft speeds increased, the limitations of wooden propellers quickly became evident, including cracking and delamination. They were also very vulnerable to damage in combat, with a single bullet through a wooden blade often causing its catastrophic failure.

While wood was easy to work with and, with sufficient skill, propellers could be carved to almost any shape, the quest for more durable propellers led to metal blades, initially made of steel. Steel offered significantly greater strength and resistance to damage, though it introduced additional challenges, such as increased weight and the need for more complex, expensive manufacturing processes. One of the earliest airplanes using steel propellers was the Handley Page O/400 bomber, which significantly improved its flight performance and reduced its vulnerability in the demanding conditions of long-range bombing missions under enemy fire.

With the formation of dedicated research institutions, such as the NACA and the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE), the aerodynamic principles governing propeller performance began to be systematically quantified. From the 1920s to the 1950s, NACA conducted wind tunnel tests and collated detailed data on propeller performance. Engineers experimented with various blade planforms, including tapered and hyperbolic shapes, as well as specific tip shapes and airfoil sections better suited to propellers. The RAE also researched propellers extensively, focusing on theoretical aerodynamic analyses, mainly by Hermann Glauert[3], supported also by wind tunnel measurements. These propeller developments laid the groundwork for more sophisticated airplane designs, contributing to the rapid evolution of aviation technology.

Materials like duralumin, an aluminum alloy invented in the mid-1920s, were used to make propellers lighter and stronger. Engineers soon began developing variable-pitch aluminum propellers, allowing pilots to adjust the blade pitch angles for optimal flight performance. This significantly improved propeller efficiency and airplane performance over a broader range of airspeeds. In the 1930s, Hamilton Standard introduced the first controllable pitch propeller. During takeoff and climbout, the pilot could use a lower blade pitch for optimal performance, then shift to a higher blade pitch for efficient cruising. This innovation soon led to the constant-speed propeller, which automatically adjusted blade pitch during flight using a governor [4] to maintain a constant rotational speed and continuously maximize the propeller’s propulsive efficiency.

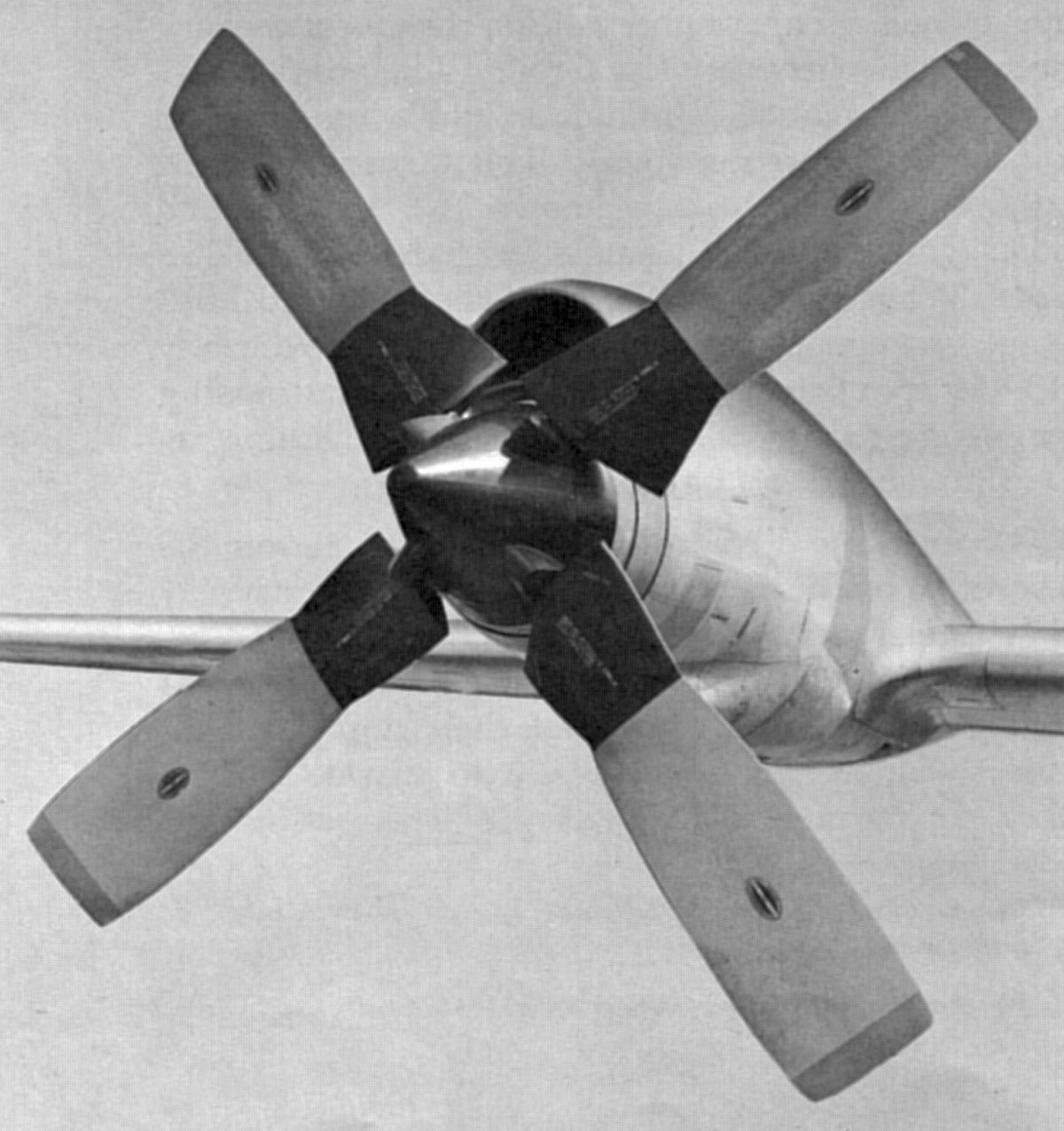

During WWII, propeller-driven aircraft technology reached new heights, with significant advancements in propeller design, aerodynamics, engine efficiency, structural reliability, and overall weight reduction. The introduction of propellers with more blades was another crucial development. Initially, two-blade and three-blade propellers were standard. Still, engineers soon realized that four-blade and five-blade designs were needed to absorb the power from increasingly powerful piston engines. Additional blades also provided smoother operation, reducing vibrations from the engine and propeller, and improving the airplane’s overall performance at higher airspeeds. As engine power levels increased further after the advent of supercharging and turbocharging, counter-rotating tandem propellers were used to prevent a single propeller from becoming prohibitively large and thereby absorbing all available engine power.

Iconic WWII aircraft, such as the British Supermarine Spitfire and the American North American P-51 Mustang, exemplified advancements in propeller and engine technology. The Spitfire, with its powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and Rotol four-bladed aluminum propeller design, as shown in the photograph below, achieved exceptional performance in terms of achievable airspeeds and operational altitude. Later models of the Spitfires were equipped with a five-bladed propeller powered by a version of the Rolls-Royce Griffon engine, representing the pinnacle of piston-engine and propeller performance. The P-51 Mustang, when fitted with a four-bladed Hamilton Standard propeller, became renowned for its long flight range, speed, and effectiveness as an escort fighter.

These technological improvements in propeller design were also applied to bombers and transport aircraft, such as the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, the Avro Lancaster, and the Douglas C-47. Propellers played a crucial role in improving the speed, altitude, and range of these aircraft, ultimately contributing to the Allied victory in WWII. The increased efficiency and reliability of propeller-driven airplanes enabled more effective long-range bombing campaigns, strategic airlift, and supply missions. Additionally, advancements in aerodynamics and engine integration enabled these aircraft to carry heavier payloads while maintaining maneuverability and endurance in combat operations.

The transition to using gas turbine (turbojet) engines after WWII soon surpassed the use of propellers in most military and commercial aviation. Nevertheless, propeller technology continued to evolve for specific applications, including high-speed fighter airplanes. However, the most significant interest in new propeller developments was in turboprop engines, which used a turboshaft to drive a propeller, offering high propulsive efficiency at lower speeds and altitudes than pure jet engines. This advancement made turboprop “jet” airliners ideal for shorter routes where fuel efficiency and short takeoff and landing capabilities, such as at regional airports, were critical.

The Lockheed L-188 Electra, which entered service in 1958, demonstrated the enduring significance of propeller-driven airplanes; one of its four-bladed propellers is shown in the photograph below. Airplanes like the Lockheed C-130 Hercules, the modern Airbus A400M Atlas, and the C-130J Super Hercules have since leveraged advances in turboprop technology to improve their efficiency, versatility, and reliability. Today, the turboprop remains a preferred propulsion system for many airplanes and can be found on high-performance single-engine aircraft, such as the Pilatus PC-12 and the Cessna Caravan 208.

While the basic engineering principles used in aircraft propeller design have remained unchanged for decades, numerous detailed improvements have led to continuous gains in propulsive efficiency and operational reliability. Propeller construction methods have continued to advance, using carbon and graphite composites to produce lighter, more aerodynamically efficient blades with reduced noise. Engineers continue to use techniques such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and computer-aided design (CAD) to further optimize propeller performance, tailoring them to specific engines, aircraft, and flight conditions.

Most modern propellers feature swept leading edges and thin airfoil sections, as illustrated in the photograph below. Scimitar propellers, which have highly swept blades made primarily of composite materials, were developed in the 1980s. Like the swept wings used on high-speed aircraft, these propeller blades delay the onset of drag rise and wave drag, allowing them to remain efficient propulsors at higher flight speeds and Mach numbers. They also reduce noise, a significant concern for all modern aircraft due to increasingly stringent ICAO noise standards. This swept-blade propeller design is used in many modern turboprop aircraft, including the ATR 72, Bombardier Dash 8, and Pilatus PC-12.

Ongoing developments in propeller designs for electrically powered airplanes focus on improving efficiency and reducing noise, particularly for urban air mobility (UAM) and unoccupied aerial vehicles (UAVs). Engineers are exploring innovative blade geometries and lightweight materials to create quiet, compact propeller systems that meet the unique demands of drones, electric airplanes, and eVTOL concepts. The goals include optimizing flight performance with multi-rotor systems and variable-pitch propellers, while leveraging advances in battery technology and manufacturing techniques. While the tipping point in favor of electric propulsion over traditional approaches is likely decades away, technology developments are progressing rapidly.

Learning Objectives

- Have an appreciation of the historical developments of propeller technology from the days of the Wright brothers to the present.

- Understand the basic operational principles of a propeller, including the methods used to calculate its thrust, the power required, and its efficiency.

- Be familiar with momentum theory and blade element theory when calculating the performance of a propeller.

- Know how to read and interpret a propeller performance chart.

- Understand the operational advantages of variable-pitch propellers compared to fixed-pitch designs.

- Know how to select a propeller to meet a performance requirement, including for low-Reynolds-number propellers.

Propeller Fundamentals

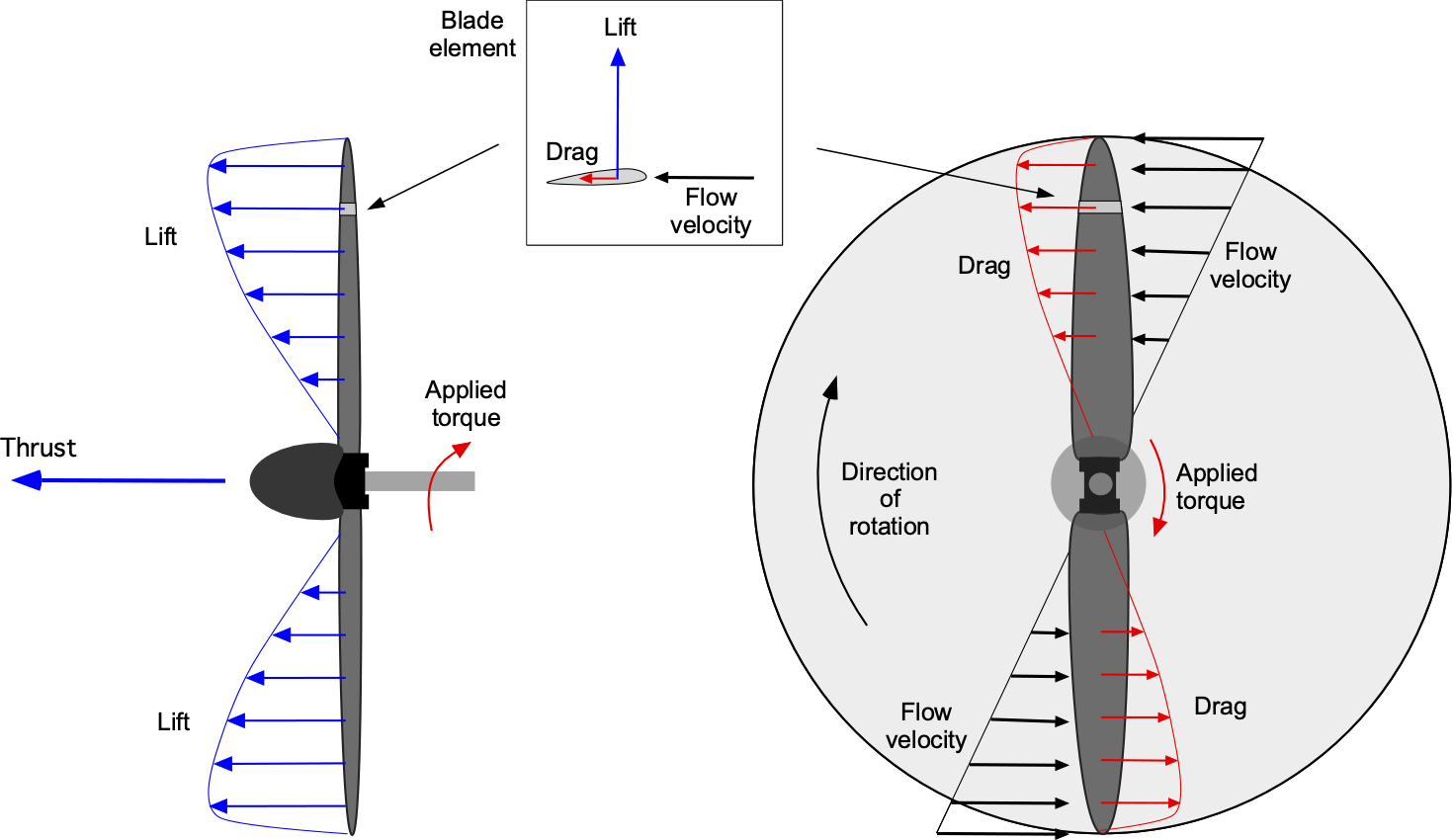

Propellers convert rotational motion into thrust by creating aerodynamic lift forces on their blades, which act as rotating wings. As the blade moves through the air, the airfoil’s shape creates an aerodynamic pressure difference between the upper and lower surfaces, generating lift. The resolved forward component of the lift vectors is known as the propeller’s thrust. The engine supplies torque to the propeller shaft, which, in turn, overcomes the drag forces on the blades and maintains their rotation. Sedulous propeller design maximizes thrust by optimizing blade geometry, angle of attack distribution, and rotational speed, ensuring that the engine’s power is converted into propulsive force with maximum efficiency.

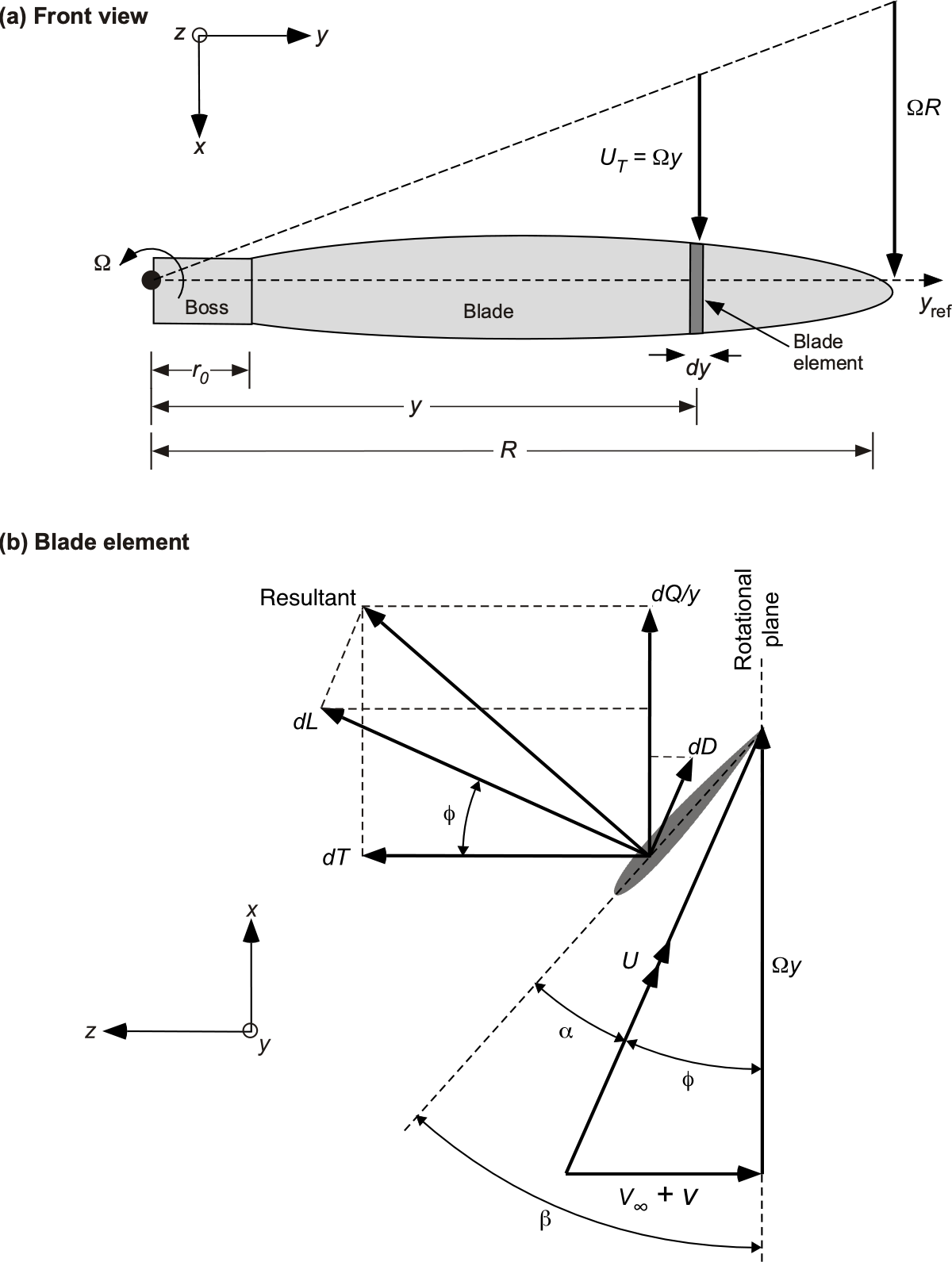

Velocity Triangle & Blade Twist

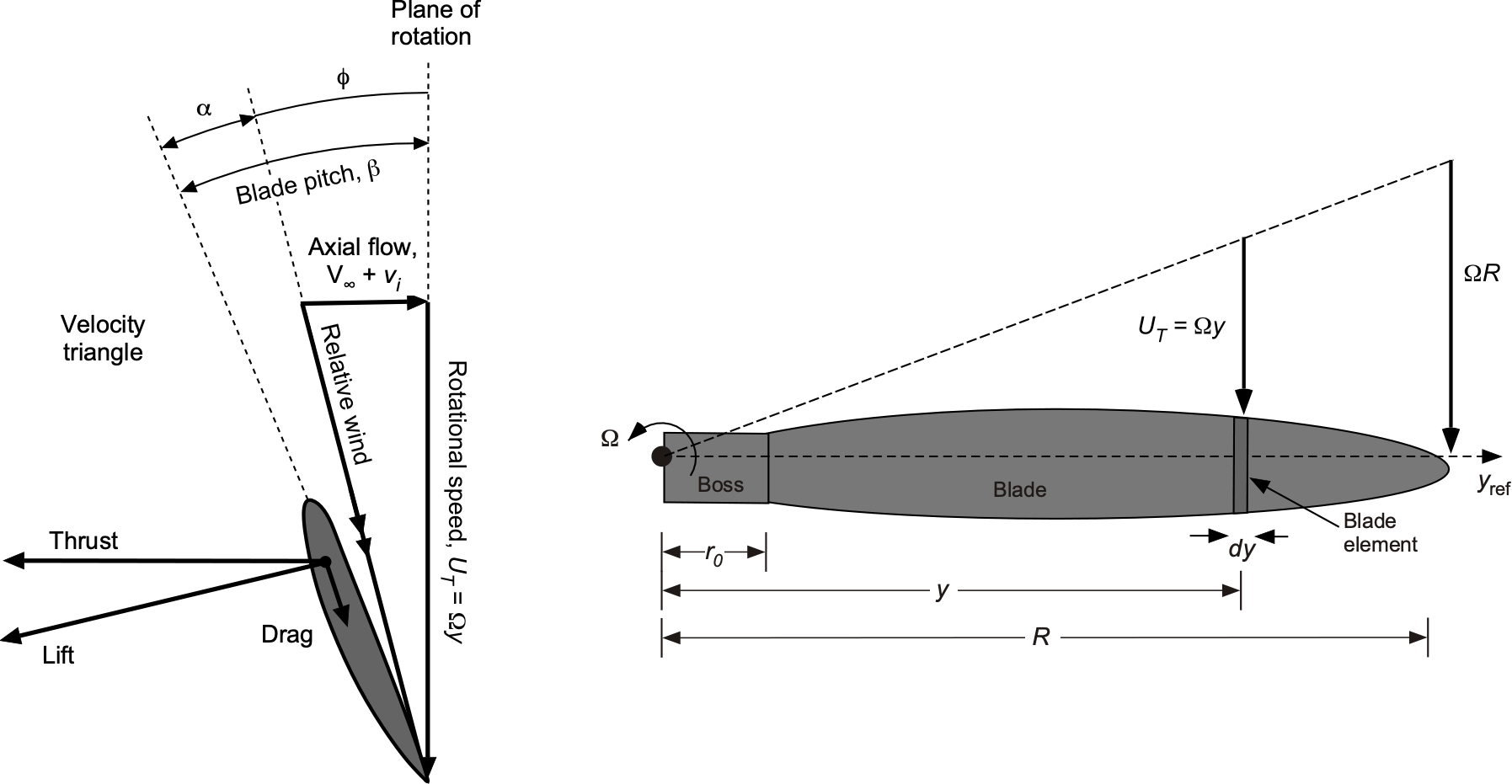

A notable design feature of propeller blades is their significant twist along their span, i.e., geometric washout. Each blade is composed of an airfoil section. Because of the variation of flow velocity along the blade, the twist ensures that the local angle of attack at each section remains near its most aerodynamically efficient value across the entire blade span. In practice, most sections should have angles of attack between about and

, or otherwise near their angle of attack for the peak lift-to-drag ratio, i.e.,

. The result is maximum thrust production for minimum torque and shaft power.

To understand why a propeller blade must be significantly twisted, consider the following analysis. Let be the radius of the propeller and let

be the spanwise distance from the axis of rotation to a blade element, as shown in the figure below. The corresponding nondimensional radius is

, and the root cutout, which is aerodynamically passive, is

. The angular velocity is

, and the tangential (in-plane) velocity increases linearly with

, i.e.,

. The local geometric blade pitch angle,

, is defined relative to the plane of rotation.

Assume that the axial velocity through the propeller disk is uniform, such that

. The total relative velocity (also known as the relative wind) at the blade section

is then

(1)

The inflow angle is

(2)

and so the sectional angle of attack is

(3)

Notice that the axial velocity is the sum of the freestream velocity (airspeed) and the induced velocity

, i.e.,

(4)

For a propeller in its normal working state during flight, , whereas for static thrust (hover)

, so that

. In either case,

is assumed to be uniform across the propeller disk, consistent with the Rankine-Froude actuator disk assumption, which is also a design goal to minimize losses.

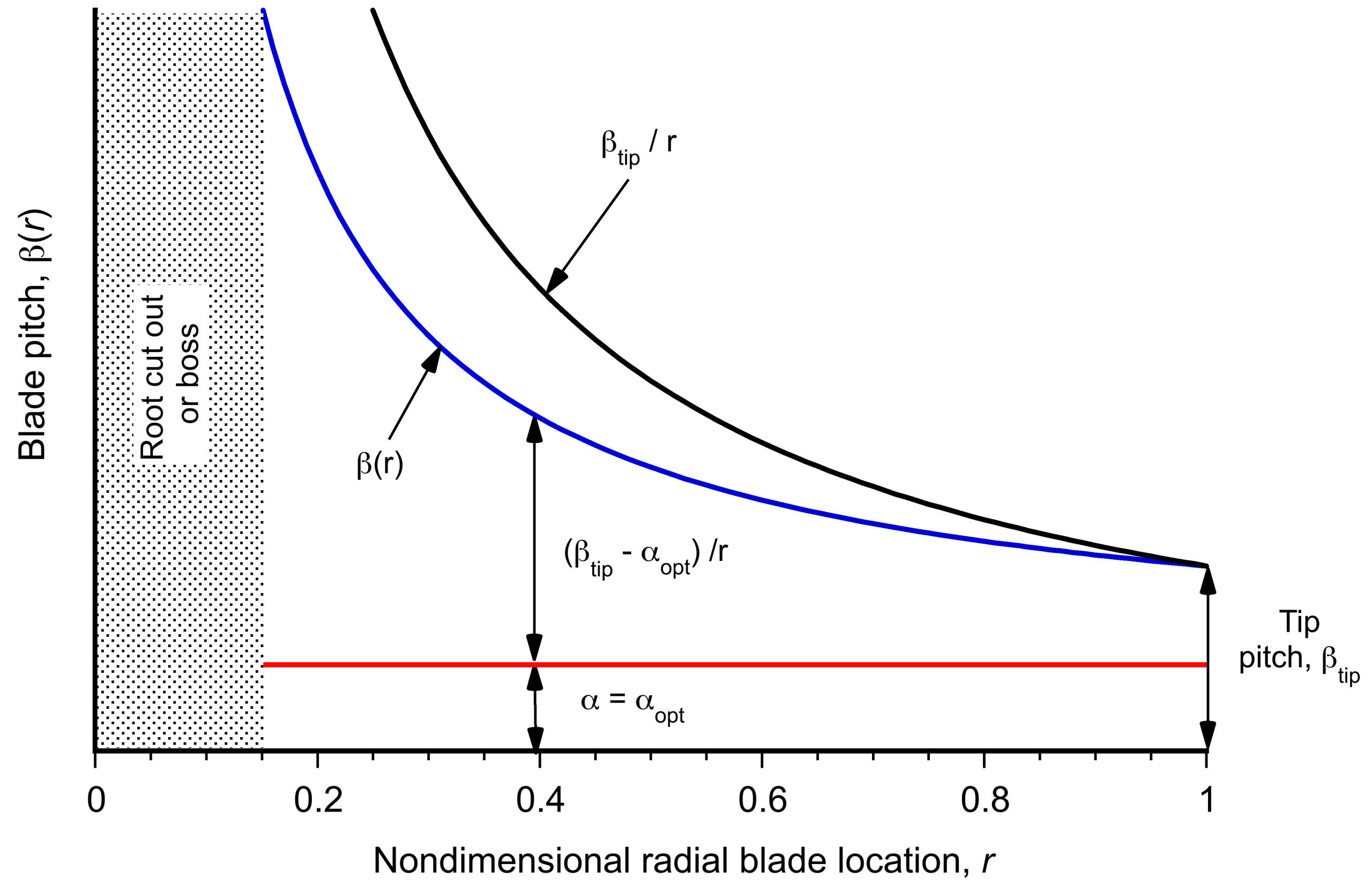

Under the assumption of a constant aerodynamic angle of attack, i.e., , it follows that

(5)

which suggests a canonical form for the twist distribution, i.e.,

(6)

because is a constant. This expression shows that

must follow a hyperbolic variation proportional to

, i.e., in general

(7)

as shown in the figure below. The twist angle is larger near the root and decreases toward the tip, thereby ensuring a constant angle of attack along the blade span. However, because of the variations in Mach number, Reynolds number, section thickness-to-chord ratio, and camber (i.e., zero-lift angle of attack, ), the best angle of attack is not necessarily a constant. The net twist will vary for different propellers based on their intended application, but the net washout angles may be as large as 40 degrees over the blade span; of course, these twist angles are significantly larger than those used on airplane wings.

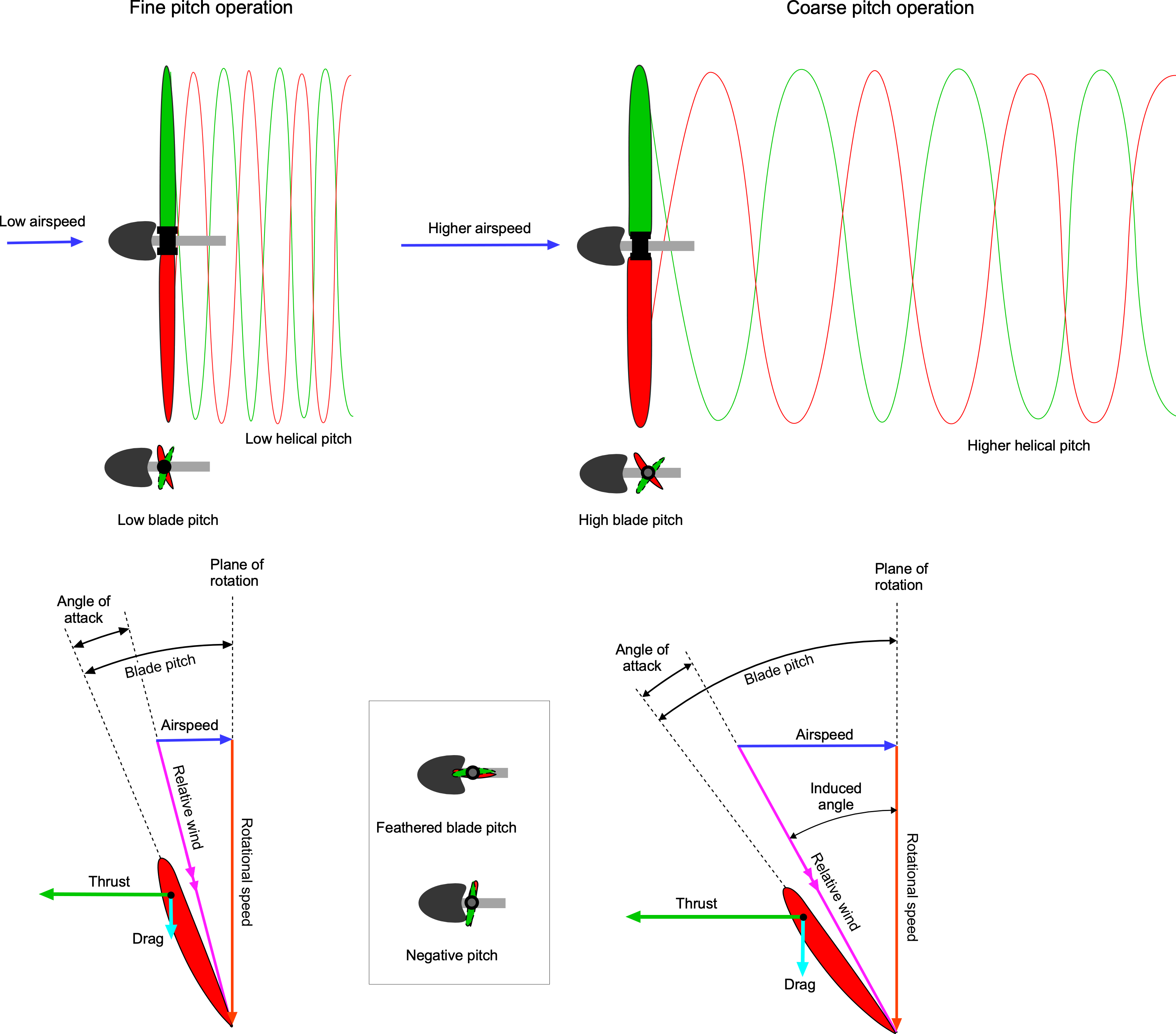

Fixed-Pitch Versus Variable Pitch

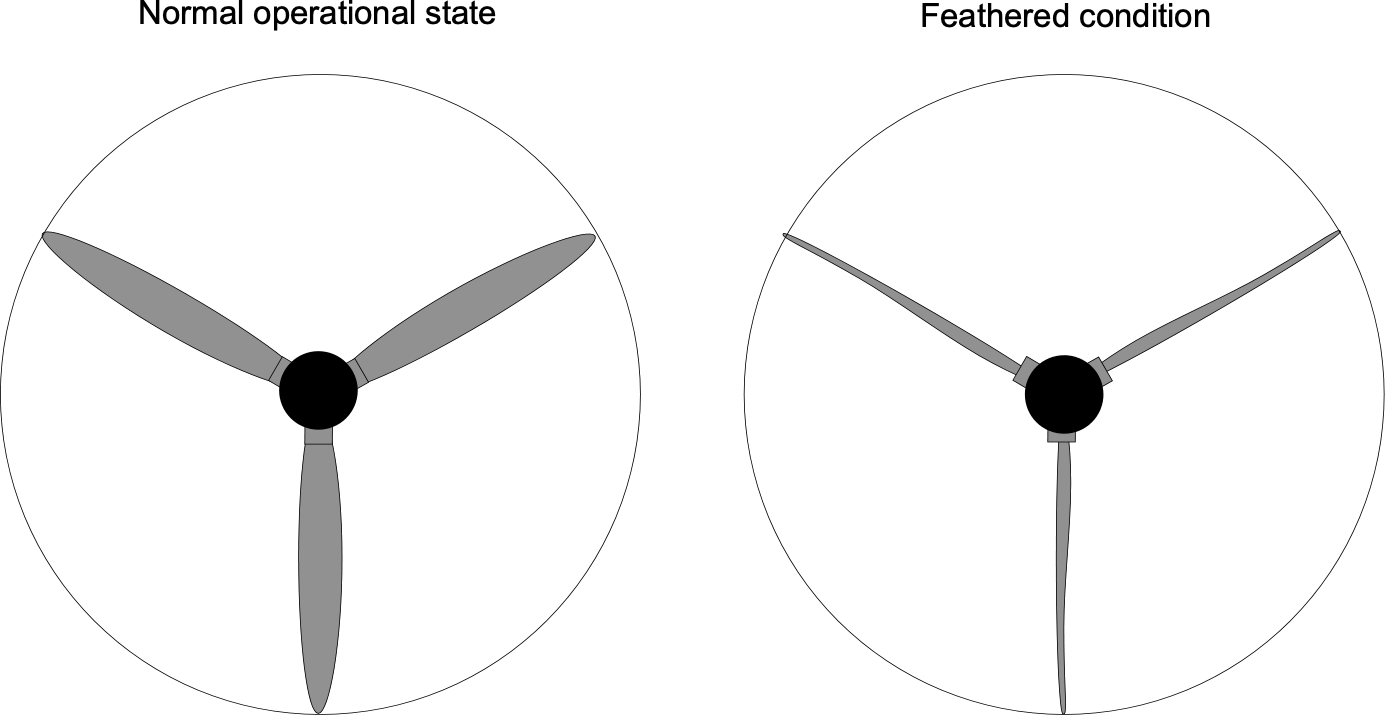

Fixed-pitch propellers have a narrow operating envelope; they are either suitable for takeoff and climb but perform poorly in cruise, or they are suitable for cruise but perform poorly in takeoff and climb. This is because at higher airspeeds, the blade section angles of attack on a propeller of fixed pitch will become progressively smaller, so the propeller produces progressively less thrust. The solution to this dilemma is to change the average blade pitch angles[5] to maintain or increase thrust production and allow the efficient operation of the propeller to be optimized as a function of the flight condition, the idea being shown in the figure below.

To maximize thrust and propulsive efficiency, a fine (low) blade pitch will be used for takeoff and landing, and a coarser (higher) blade pitch will be used for cruise flight. Regulating the blade pitch angles in this manner optimizes the propeller’s efficiency as a function of flight condition. Therefore, an aircraft equipped with a variable-pitch or constant-speed propeller can maintain high thrust and propulsive efficiency over a broader range of airspeeds. In cruise flight, a speed governor can automatically adjust the blade pitch to maintain the propeller’s constant rotational speed, thereby offloading much of the pilot’s workload for controlling the propeller pitch.

The highest thrust from the propeller will be limited by the onset of stall, just as a regular wing is limited in its angle of attack capability by stall. However, because the local incident Mach number varies from the root to the tip of the propeller, and the stall angle of attack of an airfoil decreases with increasing Mach number, the allowable angle of attack before stall decreases from the root to the tip. To this end, thin airfoil sections with higher lift-to-drag ratios and higher drag-divergence Mach numbers are used. However, the onset of stall will eventually occur if the blade pitch is increased too much, accompanied by a loss of thrust, an increase in power, and a marked drop in propulsive efficiency.

If the engine stops in flight, the propeller blades must be “feathered” into the airflow to reduce the otherwise high drag of the stationary blades. This means the leading edges of the blades will point almost directly into the airflow, as shown in the figure below. In this regard, strong springs are used on a constant-speed propeller so that the blades are automatically forced into the fully feathered position if the propeller stops rotating. The drag of an unfeathered stationary propeller is considerable, so an airplane with a fixed-pitch propeller will inevitably have a poor glide ratio. The propeller blades may sometimes be set to a negative pitch to produce negative thrust, thereby acting as an aerodynamic brake during landing. However, this latter feature is usually found only in high-performance turboprop aircraft.

Types of Propellers

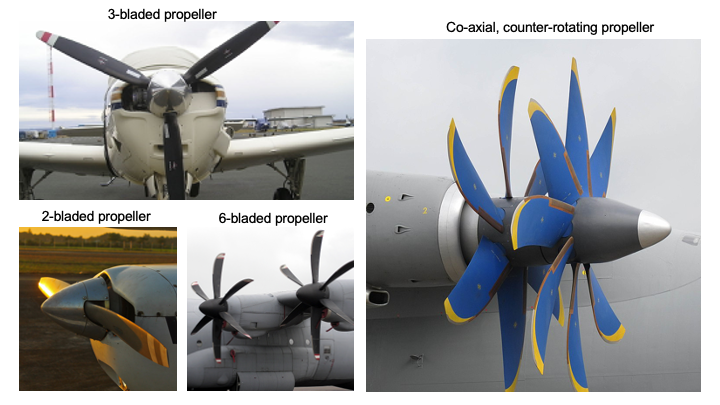

Many propeller types are in use, ranging from those with just two blades to those with four or more blades, some with fixed pitch and others with variable pitch, as shown in the photographs below. In addition, some propellers may have swept blades, a design feature that reduces compressibility drag at the tips when the airplane operates at higher flight speeds, similar to the design used on the wings of supersonic airplanes. As engine power increases, more blades (or a greater blade area) are required to deliver the power to the air as useful thrust. In some cases, to prevent the propeller diameter from becoming too large, counter-rotating propellers may be used to absorb the high power available from the engine shaft and generate thrust.

Propellers with more blades tend to be relatively more efficient (when compared at the same thrust and total blade area) because they act more like an actuator disk.[6] However, the propeller’s net efficiency depends on other factors, including operating speed (rpm or rps),[7] tip Mach number, blade section Reynolds numbers, diameter, and blade pitch. Today, there is an increasing emphasis on reducing propeller noise, which has driven engineers of modern designs (even on general aviation airplanes) to use more blades and smaller diameters with lower tip Mach numbers.

What is the difference between propeller power and torque?

Torque, given the symbol , is the rotational action applied to the propeller shaft, while angular velocity,

, is the speed at which the propeller rotates, measured in radians per second. Power,

, represents the rate at which energy is transferred and is given by the equation

. A high torque with low rotational speed results in lower power, whereas a lower torque with high rotational speed can still generate significant power. The key to efficient propeller performance is balancing

and

to achieve optimal thrust and efficiency across different flight conditions. For example, consider a propeller with high torque but lower rotational speed: if

= 50 Nm and

= 100 rad/s, then the power is

= 50

100 = 5000 W = 5 kW. Alternatively, if the propeller operates at lower torque but higher speed, say

= 25 Nm and

= 200 rad/s, the power remains the same at

= 25

200 = 5000 W = 5 kW.

Momentum Theory of the Single Propeller

The Rankine propeller theory,[8] also known as the Rankine-Froude theory,[9] provides a fundamental framework for understanding propeller performance. This theory models the propeller as an idealized actuator disk that imparts momentum to the air, creating a pressure jump across the disk. The physical problem is that the propeller does work on the air as it passes through the propeller disk; i.e., the propeller applies a force to the air in the downstream direction, changing its momentum and kinetic energy. As a result, the force on the propeller, which is produced because of a pressure difference between one side of the propeller disk and the other, is in the opposite direction to the force on the fluid, i.e., the thrust is directed upstream.

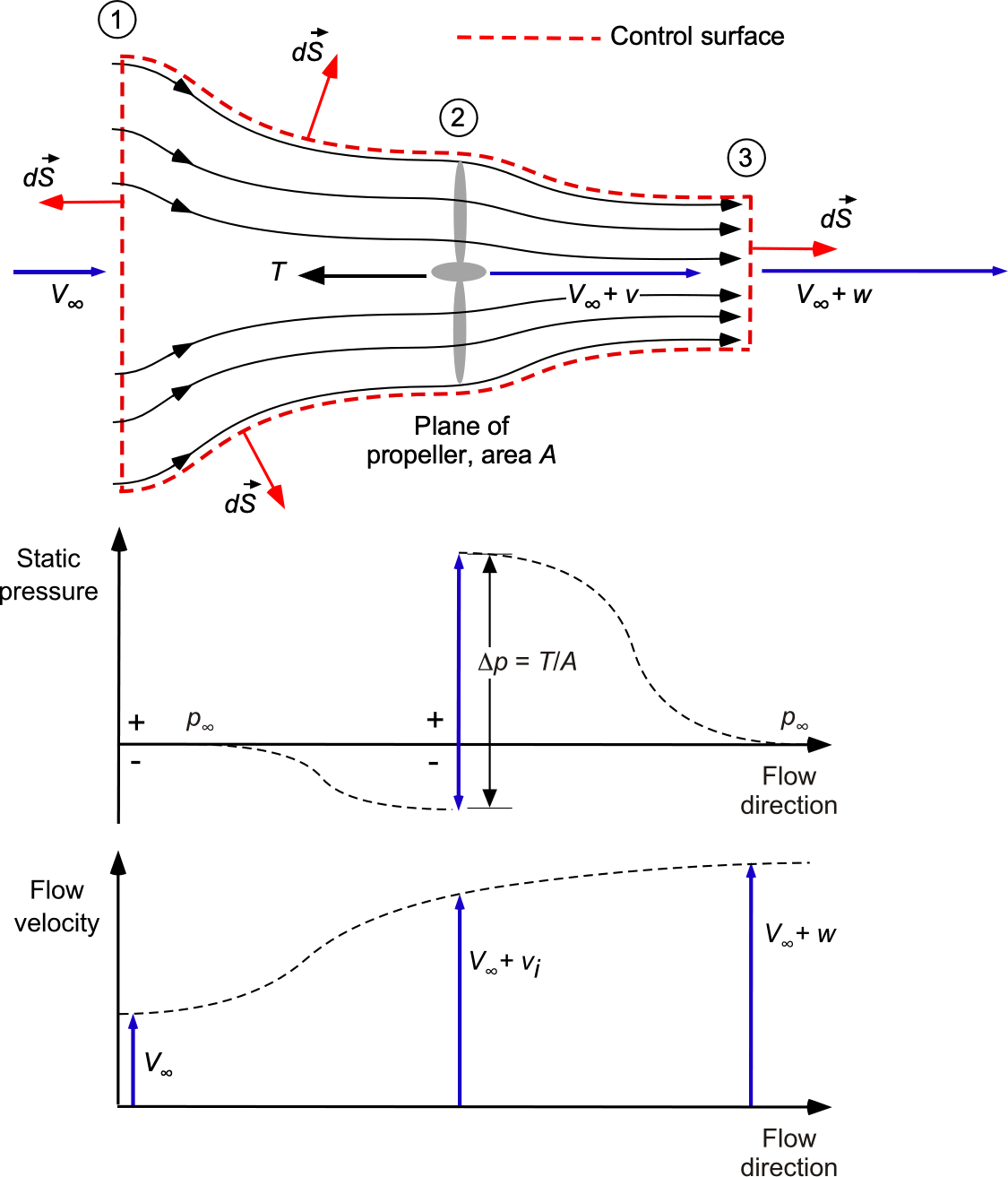

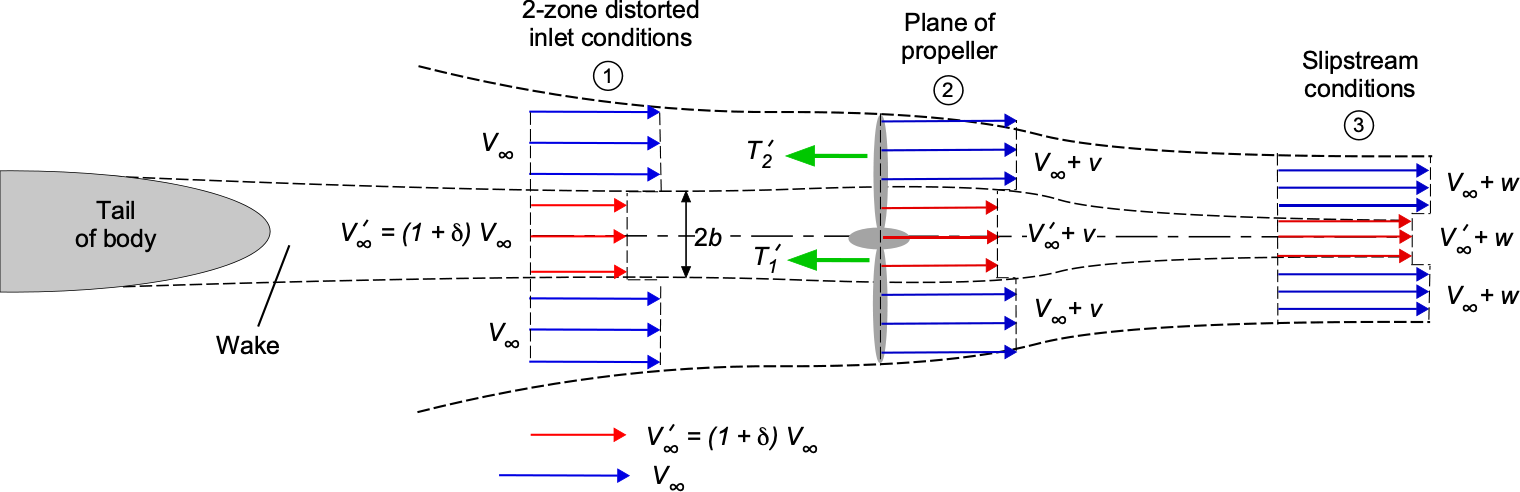

Flow Model

The flow model for the single propeller problem is shown in the figure below. The upstream and downstream sections labeled 1 and 2 bound the control volume. Remember that when the integral form of the conservation equations is used, then points out of the control volume by convention. The upstream or freestream (undisturbed) velocity is

, and the pressure there is

. It will be assumed it is uniform, which is a reasonable assumption unless the propeller is affected by a wing or another part of the airframe. It will also be assumed that a one-dimensional, steady, incompressible flow applies throughout, so that the flow velocities change only with downstream distance.

The flow is entrained and accelerated into the propeller, so at the plane of the propeller, the flow velocity is plus an increment

, i.e., the velocity there is

. The static pressure will also change there. The propeller works on the air to increase its momentum and kinetic energy, so the velocity downstream is

. In the slipstream, the static pressure will also recover to ambient conditions, i.e., the pressure downstream will slowly return to

.

Application of the Conservation Laws

The conservation of mass requires a constant mass flow through the control volume. The areas of the upstream and downstream parts of the streamtube (stations 1 and 2) are unknown, but the area of the propeller disk, , is known (

where

is the diameter of the propeller), so the mass flow rate through the propeller (and hence through the boundaries of the control volume) is

(8)

The conservation of momentum requires that the net change in momentum of the fluid (as applied by the propeller) is equal to the force on the fluid, i.e.,

(9)

where the direction of is downstream, and the thrust on the propeller,

, is in the opposite direction (pointing left in the figure) so that

(10)

The conservation of energy states that the work done on the propeller (to move it forward) plus the work done on the air (to create the aerodynamic force) must be equal to the gain in kinetic energy of the slipstream as it passes through the propeller, i.e.,

(11)

so that the power required for the propeller to produce the thrust

is

(12)

Notice that the term on the left-hand side of the above equation can be written as the sum of the

term, which is the work done to move the propeller forward, i.e., the useful work. The

term is the work done on the air or the induced power loss; the induced power is an irrecoverable power loss, which constitutes a loss in the propeller’s efficiency in producing useful work.

Induced Velocity

The induced velocity in the plane of the propeller can be found by substituting Eq. 10 into Eq. 12, which gives

(13)

Expanding out and simplifying gives

(14)

This result gives the relationship between and

, i.e.,

(15)

For the next step, take Eq. 10 and substitute in Eq. 8 (mass flow rate) and the connection between and

(

) to get

(16)

The induced velocity in the plane of the propeller can now be solved for in terms of thrust, i.e.,

(17)

and expanding out gives

(18)

The ratio is called the propeller disk loading. It can be seen that the latter equation is quadratic in

, which can be solved to get

(19)

for which there are two roots, i.e., from the term. Only one can be a physical root (the other one violates the assumed flow model, where the flow is assumed to be through the propeller from left to right), which is

(20)

(21)

Therefore, it will be apparent that for any given propeller producing a thrust , its induced velocity

will decrease rapidly with increasing airspeeds, i.e.,

. In the design of a propeller in its normal propulsive state, the induced losses can often be ignored compared to the profile losses.

Power Required

The corresponding power required to drive the propeller and produce a thrust, , becomes

(22)

The useful power for propulsion is , and the second term is the irrecoverable induced loss. Rearranging the preceding equation gives

(23)

This power equation can also be written non-dimensionally as

(24)

Notice that in the limiting case when the airspeed, , becomes high, then

, meaning that the induced losses tend to zero. Therefore, a greater fraction of the power delivered to the propeller goes into useful work to propel the airplane forward. However, in practice, some additional profile (non-lifting) power,

, will be required to overcome the viscous (shear) drag of the blades so that the total power required,

, can be written as

(25)

Propulsive Efficiency

The propulsive efficiency of the propeller can also be derived from the preceding analysis. The useful power for propulsion is so the efficiency of the propeller,

, can be written as

(26)

which shows that the propeller becomes more efficient at higher airspeeds, where the induced velocity becomes a smaller fraction of the airspeed. This result also confirms that the efficiency of the propeller at higher airspeeds as will be dictated by the profile losses on the blades, i.e.,

(27)

The profile power losses, denoted by , depend on the blade sections and the net blade area, which is measured by the propeller’s solidity or activity factor.

Activity Factor & Solidity

A parameter called the activity factor, , was used in the earliest days of propeller design. Its definition has originated within the industry rather than in any scientific context. The

is considered a measure of the propeller’s “aerodynamic activity” or effectiveness in producing thrust and is defined as

(28)

where is the number of blades,

is the reference chord length of the blade, and

is the diameter of the propeller. A higher activity factor indicates that the blades have more lifting area, enabling them to generate more thrust.

Definitions and Nomenclature

Notice that both and

have historically been used to denote the propeller diameter, and they may be used interchangeably. In the NACA literature, the preferred term for diameter is

. Similarly, the definition of the reference chord has been inconsistent, ranging from the local chord value at the 70%, 75%, or 80% radius station to a weighted chord based on the platform area distribution. So, it is essential to verify the specific definition used in any given context. Likewise, propeller efficiency may be denoted by

or

, with \ (\ eta_p \) preferred in modern usage.

Solidity, given the symbol , is a related dimensionless parameter, which is defined as the ratio of the total blade area to the disk area swept by the propeller, i.e.,

(29)

The scientific literature commonly uses total solidity for the entire propeller and “local” solidity for a specific blade section, which is more geometrically meaningful than the activity factor. The local solidity is given by

(30)

Notice that a reference or “mean” chord is used when considering total solidity. The most appropriate mean chord for a propeller is a “torque” weighted chord based on

(31)

where =

and

= 0.15

is a starting point or root cutout that accounts for the presence of the propeller hub or “boss.”[10] The reasoning for this

weighted chord equation is that the blade sections near the tips are much more aerodynamically effective than those near the root end and so more affect the propeller’s performance. In this regard, other definitions of the activity factor have been used, including

(32)

Therefore, verifying the definitions used when analyzing propeller data in a specific context is essential, especially before conducting any comparative analysis. To be meaningful, the performance characteristics of different propeller blade shapes or numbers of blades, for example, should be performed based on the same value of the activity factor or overall solidity.

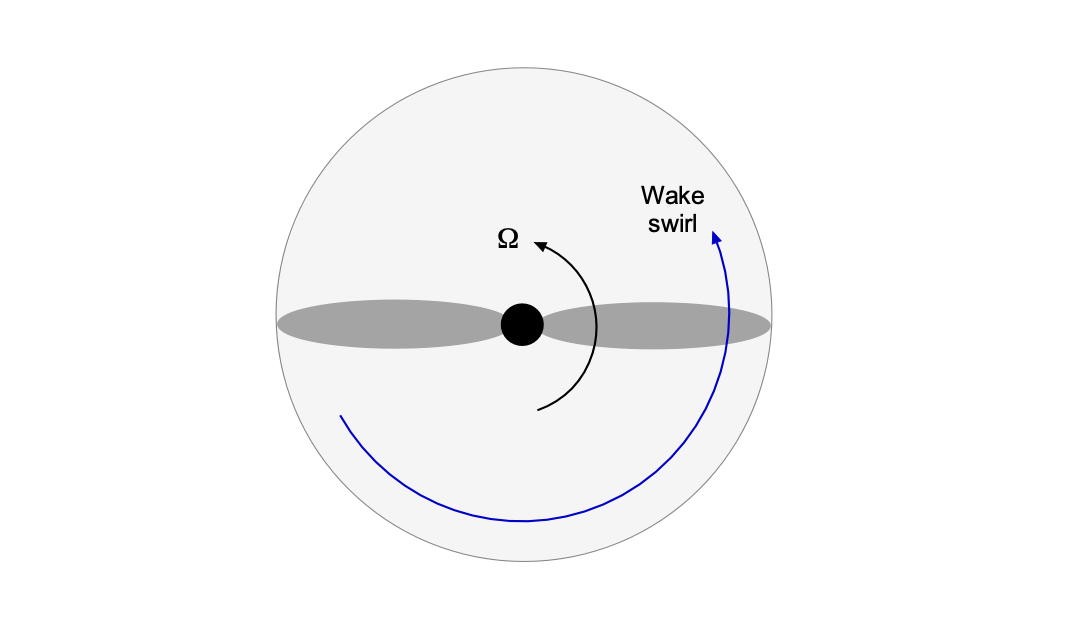

Wake Swirl Effects

Incorporating the swirl into the momentum theory involves adding a tangential in-plane velocity component to the otherwise purely axial flow, i.e., a rotational component parallel to the rotor’s plane of rotation. Rankine’s actuator disk theory considers only the axial momentum balance, assuming the flow is steady, inviscid, and incompressible, although Glauert further considered this term. When swirl is included, the average angular velocity component of the downstream flow must be considered, as it affects the power requirements and propulsive efficiency. While the effects are best considered within the framework of blade-element theory, an approximation can be derived from momentum theory.

Propeller swirl refers to the rotational velocity of the air in the downstream wake behind the plane of a propeller, which, in effect, creates a spiral or corkscrew flow, as shown in the figure below. This effect occurs because of viscosity, in which the propeller blades drag a certain amount of fluid as they rotate. The upshot imparts a rotational velocity component to the fluid, , as a consequence of generating thrust. The higher the thrust and torque, the more significant his effect. Swirl causes efficiency losses because some kinetic energy is lost to rotational fluid motion, in addition to that from thrust generation.

Recall that the thrust generated by a propeller with a pure axial velocity component,

, is given by

(33)

where is the mass flow rate through the propeller. The power

required to generate this thrust, considering the presence of an average swirl velocity,

, is

(34)

where the effective velocity, , is given by

(35)

Therefore, the power required is

(36)

which is greater than the power required for a pure translational change in momentum through the propeller.

In the wake of a propeller, the tangential velocity component, , can be derived from the angular momentum imparted by the propeller blades. The torque,

, generated by the propeller can be calculated using the relationship between torque and power, i.e.,

(37)

where is the power absorbed by the propeller and

is the angular velocity of the propeller. The time rate of change of angular momentum, which is a torque, is given by

(38)

where is the angular momentum. By using the relationship between torque and angular momentum, the effective radius at which the torque acts can be considered as the mean aerodynamic radius of the propeller, which can be approximated by

(39)

where is the propeller’s radius (=

). Finally, the average tangential velocity,

, is

(40)

In practice, the effect of wake swirl on propeller performance is minimal, perhaps reducing the overall propulsive efficiency by 1% to 2%. However, for large propellers driven by high-torque engines, the effects may reach 5%. Coaxial counter-rotating propellers, ducted propellers, and swirl recovery vanes have been employed to mitigate wake swirl and enhance net propulsive efficiency.

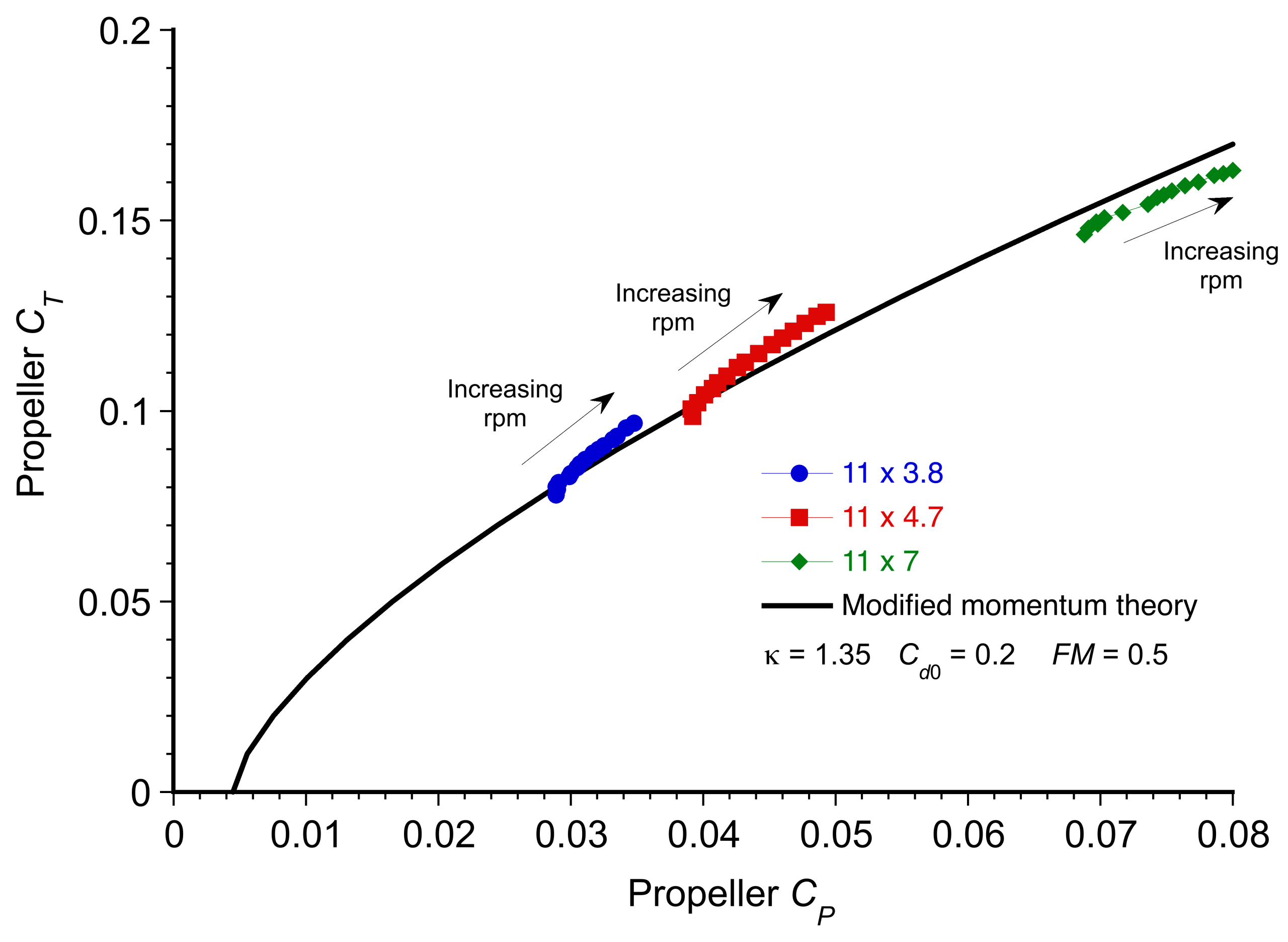

Propeller Performance Coefficients

The thrust coefficient for a propeller is a non-dimensional thrust and is defined as

(41)

where is the thrust generated by the propeller,

is the propeller’s diameter, and

is the number of revolutions of the propeller per second (rps). If the rotational angular velocity of the propeller is

, then

. The rotational speed is often measured in revolutions per minute (rpm), so rpm = 60

rps = 60

.

For a propeller, a non-dimensional airspeed called a tip speed ratio or advance ratio, given the symbol , is defined by

(42)

Finally, the power coefficient for a propeller is defined as .

Notice that the definitions of propeller thrust coefficient, advance ratio, and power coefficient differ from those used for helicopter rotors. It is essential not to confuse them. The table below clarifies the differences, where = 2

.

| Rotating-wing system | Thrust coefficient, |

Power coefficient, |

Advance ratio |

| Helicopter rotor | |||

| Propeller |

The momentum theory results for a propeller can be written in coefficient form. For the induced velocity, then

(43)

and for the induced power, then

(44)

The corresponding propulsive efficiency is then

(45)

Momentum Theory of the Tandem Propeller

Tandem coaxial propellers are arranged on the same axis but rotate in opposite directions, allowing for a more compact design than separate, non-coaxial propellers. Additionally, the opposing rotation of the propellers cancels out torque reaction effects, which can be very significant when large amounts of power and torque are being transmitted from the engine. In a tandem propeller system, two propellers are aligned along the same axis but operate at different stations, effectively working on the same slipstream. The second propeller acts on the accelerated flow produced by the first, leading to further acceleration and additional thrust.

There are two conditions of interest:

- The rear propeller is sufficiently separated to operate in the slipstream and induced velocity field of the front propeller.

- Both propellers are located so close that they share the same induced velocity.

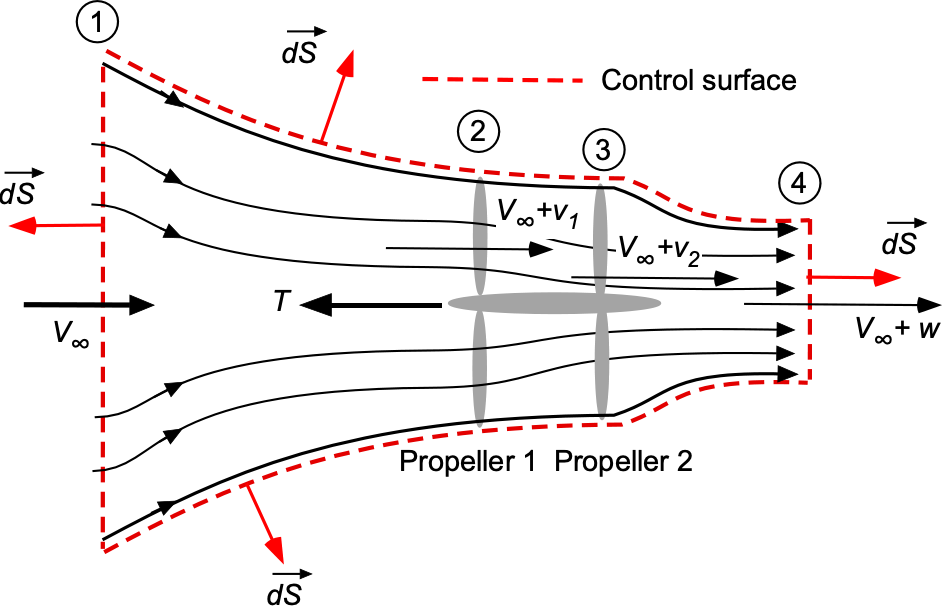

Separated Tandem Propellers

The mass flow rate through both propellers must be conserved for the tandem system, as shown in the figure below. If the first propeller increases the velocity from to

, and the second propeller further increases it to

, the mass flow rates through each propeller are

(46)

The thrust produced by each propeller can then be determined, i.e.,

(47)

The total thrust generated by the tandem system is then the sum of the thrusts produced by each propeller, i.e.,

(48)

The total power required is the sum of the power required by each propeller, i.e.,

(49)

The addition of the profile power is necessary to account for the drag associated with the propeller blades. It affects the overall efficiency of both single- and tandem-propeller systems. The efficiency of each propeller can be expressed as

(50)

For a tandem configuration with two propellers, the efficiency of each propeller is

(51)

Therefore, the overall efficiency of the tandem system can then be expressed as

(52)

Including profile power affects the efficiency calculation because both thrust production and the power required to overcome drag must be balanced. If the profile power becomes significant relative to the thrust generated, it will reduce overall efficiency, particularly at higher speeds where profile losses predominate. In this regard, it will be noted that

(53)

which is the same result as found for the single propeller, i.e., its net propulsive efficiency mostly depends on the profile power required.

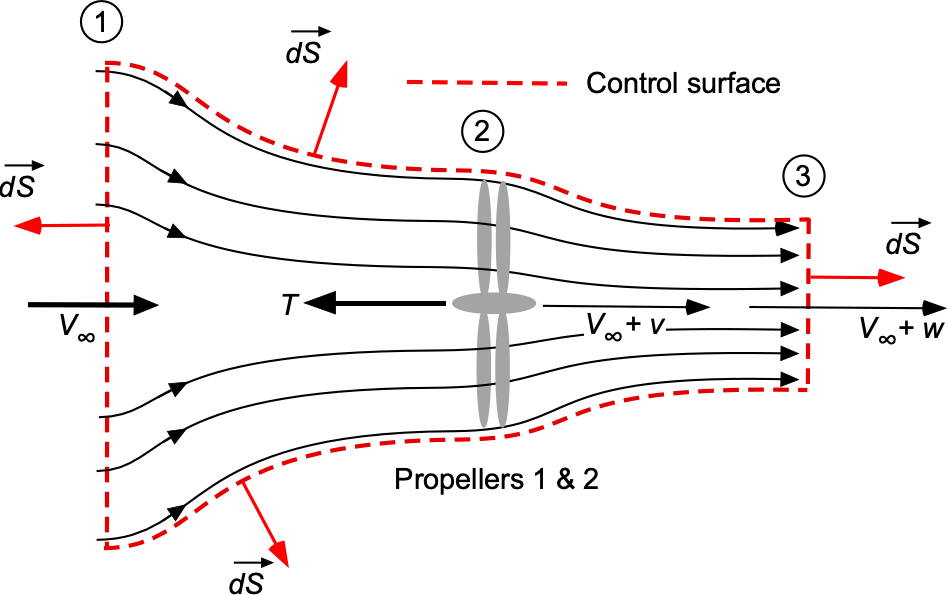

Tandem Propellers with Shared Induced Velocity

Now consider two tandem propellers positioned closely enough to share the same induced velocity increment , as shown in the figure below. The flow velocity at the propeller planes is

. The analysis simplifies under the assumption that the induced velocity is the same for both propellers. The mass flow rate through the tandem propeller system is

(54)

where is the area of each propeller disk, which is assumed to be the same for both propellers.

The thrust generated by each propeller can be expressed as

(55)

Because both propellers share the same induced velocity , the total thrust is

(56)

The power required for each propeller is given by

(57)

and

(58)

Therefore, the total power required is

(59)

The efficiency of the tandem propeller system can be analyzed by considering the ratio of useful work to the total power required. The useful work is related to the thrust produced and the forward velocity, . The efficiency of each propeller can be expressed as

(60)

Incorporating the profile power associated with the drag of the propeller blades, the overall efficiency of the tandem system can be expressed as

(61)

which again comes to

(62)

Comparing Efficiencies

A common issue in evaluating tandem versus single-propeller designs is the basis for comparison, such as constant net thrust, equal power input, or equivalent solidity, i.e., the ratio of blade area to disk area. Within the framework of momentum theory and its inherent assumptions, no configuration is inherently superior. At higher airspeeds, the profile power required by the blades becomes the dominant factor in determining net propulsive efficiency. Although counter-rotating propellers can recover some energy from wake swirl, this effect contributes only marginally to overall efficiency. It is rarely significant enough to favor one configuration over the other.

When comparing propulsive efficiencies, it is essential to account for the added complexity of managing power distribution between propellers, as well as the overall weight efficiency of the propulsion system. Depending on the specific design choices and operating conditions, a tandem propeller system may outperform or underperform relative to a well-optimized single propeller. The primary advantage of a tandem configuration is its ability to deliver the same power as a single large propeller while using a smaller overall diameter. Ultimately, the effectiveness of any propeller system depends on careful design and optimization to meet the required performance goals, subject to constraints such as size, weight, and cost. Generally, more blades result in higher weight and increased costs.

General Propeller Performance

A more accurate way to predict a propeller’s performance is to use blade-element theory, which can also aid in designing propeller blades for optimal efficiency. Developing a computer program to calculate propeller performance using the blade-element method is a relatively straightforward task. The principle used here is calculating the angle of attack and the corresponding lift and drag at each propeller blade section, as shown in the figure below. All blades are twisted along their span from root to tip, which is done to achieve good aerodynamic efficiency. Therefore, the local blade pitch varies from point to point along the span.

Notice that the relative flow angles and, hence, the angle of attack of the blade element are obtained by using the vector addition of the relative velocity components, i.e., the vector sum of the rotational velocity, , of the blade element as it rotates about the shaft and the freestream velocity,

, where the span position from the rotational axis is denoted by

. This combination yields what is typically referred to as the velocity triangle, which helps visualize and calculate the relative flow angles.

In the propeller theory, it is usually assumed that the induced velocity, , is small compared to the freestream (flight) velocity, i.e.,

, and can be neglected. However, at lower airspeeds, a good approximation for the average induced velocity over the propeller disk can be obtained using Eq. 20, i.e.,

(63)

Because is a function of thrust,

, and thrust is a function of

, including the induced inflow, an iterative approach is required.

Theoretical Development

The local pitch of the blade is as it varies along the span, so the angle of attack

of any blade section is

(64)

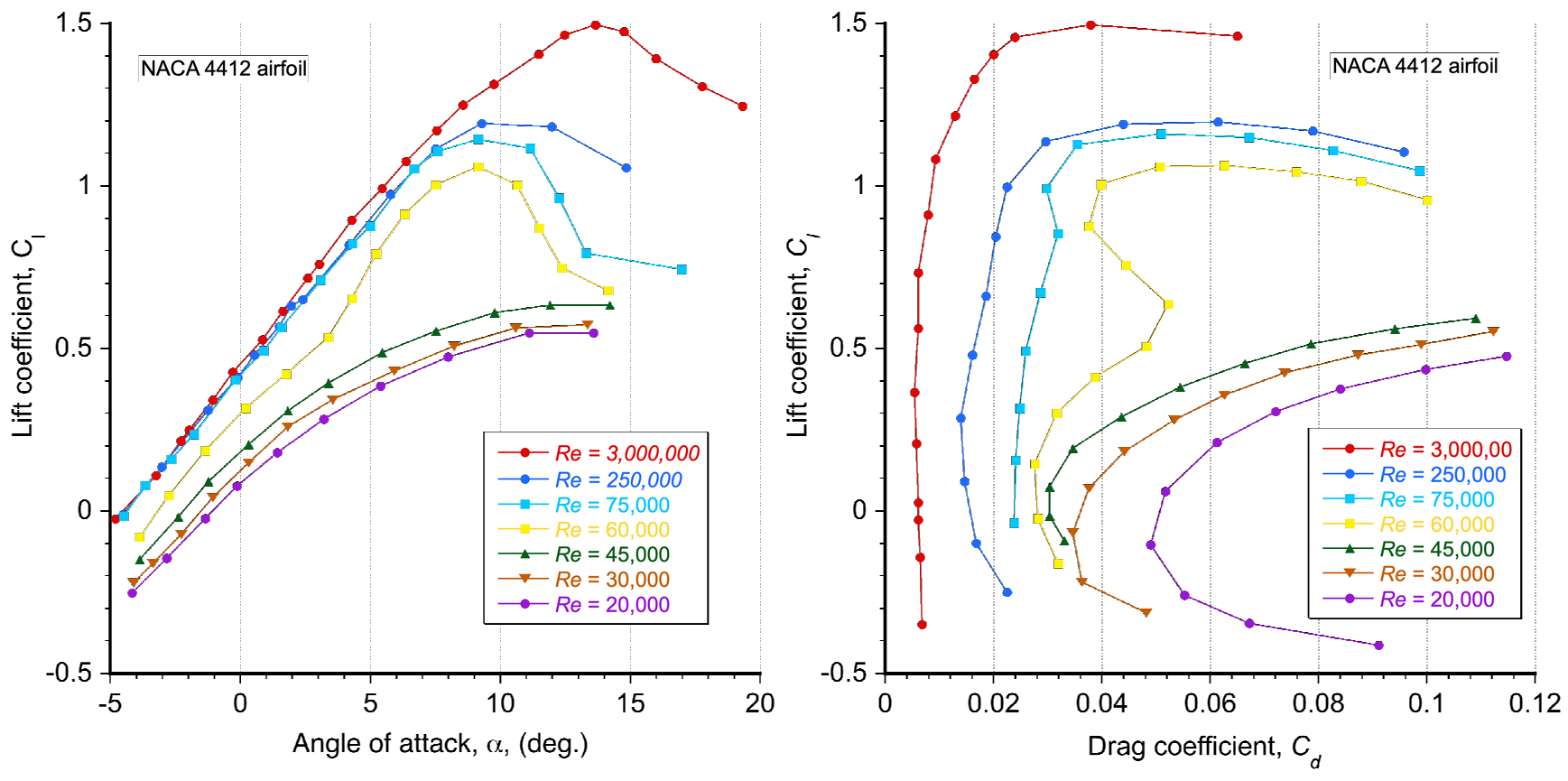

The lift coefficient on the blade element then follows as the product of the angle of attack of the blade and the local lift-curve slope of the airfoil section, i.e.,

(65)

where is measured from the zero-lift angle, recognizing that the lift-curve slope

will depend somewhat on the shape of the blade section used, as well as the local incident Mach number at the section, and to some extent, the Reynolds number too. The lift on a blade element will be

(66)

where is the local chord of the blade (

is the area of the blade element), and the resultant local velocity at the blade element,

, is

(67)

When the lift on all the sections of the propeller blade is obtained, then the net thrust of the propeller can be obtained by resolution of the local lift vectors in the direction of the thrust component, followed by spanwise integration, i.e.,

(68)

where is the number of propeller blades, and

is the propeller’s radius. The component of drag that affects thrust can be ignored. Additionally, it is reasonable to assume that the problem exhibits axisymmetry. Hence, the angles of attack at any given blade station are the same for any rotational angular position of the propeller blades. The integration process is usually performed numerically.

By analogous arguments, the power required to rotate the propeller will be

(69)

where is the local profile drag that again depends on the airfoil shape used on the blade and the incident Mach number. Notice the inclusion of the moment arm

to get to the torque (torque is a moment, so the product of a force times a distance or “arm”), and power is just the product of torque and angular velocity. In this case, however, the component of the lift

(which is the induced drag) will contribute to the net drag of the section and, hence, the torque and power required to rotate the blades.

If the section drag coefficient is known, then

(70)

However, the challenge with a propeller is to properly represent the section because it depends on the Mach number, in this case, the helical Mach number, i.e.,

(71)

where is the local speed of sound, i.e.,

). Of course, suppose the helical Mach number becomes too large and exceeds the drag divergence Mach number of the airfoil sections. In that case, the propeller’s efficiency will decrease rapidly.

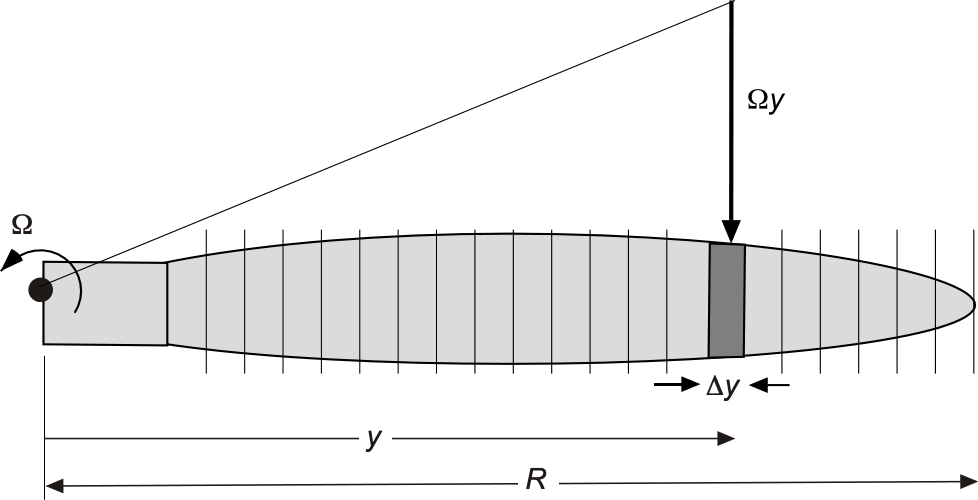

Numerical Implementation

The propeller blade can be discretized into segments, as shown in the figure below. To give any reasonable definition of the spanwise aerodynamic loads,

should be between 30 and 100. Each segment is then small enough to assume constant flow properties. Let

denote the spanwise position of the

-th segment, where

, and let

be the spanwise width of each segment.

For each segment, the resultant local velocity, , is computed using

(72)

and so the inflow angle is

(73)

The local angle of attack is then obtained using

(74)

The local lift coefficient, , is

(75)

If the drag coefficient is known or assumed, e.g.,

, it can be used directly; otherwise, the normal process is to interpolate from airfoil data tables (i.e., a table look-up approach) based on the local helical Mach number

. Reynolds number effects can also be included if such data are available.

Computing the lift force, , and the drag force,

, on each segment gives

(76)

Finally, the thrust and power contributions from all segments are then summed up using

(77)

which, for simplicity of illustration here, uses the trapezoidal rule of integration.

MATLAB code to implement the blade element theory analysis of a propeller. Including the inflow velocity is left as an exercise for the reader.

Show code/hide code.

% Constants and input parameters

rho = 1.225; % Air density (kg/m^3)

Omega = 200; % Rotational speed (rad/s)

V_inf = 50; % Free-stream velocity (m/s)

N_b = 3; % Number of blades

R = 1.5; % Propeller radius (m)

N = 100; % Number of segments

c = 0.1; % Chord length (m)

C_l_alpha = 5.7; % Lift-curve slope

C_d = 0.01; % Profile drag coefficient

% Discretize the blade span

y = linspace(0, R, N);

dy = y(2) – y(1);

% Initialize variables

J = V_inf / (Omega * R); % Advance ratio

beta_range = deg2rad(10:1:30); % Range of blade pitch angles in radians

C_T = zeros(size(beta_range));

C_P = zeros(size(beta_range));

for k = 1:length(beta_range)

beta = beta_range(k);

% Initialize variables for each pitch angle

V = sqrt((Omega * y).^2 + V_inf^2);

phi = atan(Omega * y / V_inf);

alpha = beta – phi;

% Lift coefficient

C_l = C_l_alpha * alpha;

% Calculate lift and drag forces on each segment

dL = 0.5 * rho * V.^2 * c .* C_l * dy;

dD = 0.5 * rho * V.^2 * c * C_d * dy;

% Thrust and Power calculation

T = N_b * sum(dL .* cos(phi));

P = Omega * N_b * sum((dL .* sin(phi) + dD .* y) * dy);

% Non-dimensional coefficients

C_T(k) = T / (rho * (Omega^2) * (R^4));

C_P(k) = P / (rho * (Omega^3) * (R^5));

end

% Plot the results

figure;

plot(J, C_T, ‘-o’);

xlabel(‘Advance Ratio, J’);

ylabel(‘Thrust Coefficient, C_T’);

title(‘Thrust Coefficient vs. Advance Ratio’);

figure;

plot(J, C_P, ‘-o’);

xlabel(‘Advance Ratio, J’);

ylabel(‘Power Coefficient, C_P’);

title(‘Power Coefficient vs. Advance Ratio’);

% Output results

fprintf(‘Advance Ratio (J): %.2f\n’, J);

fprintf(‘Thrust Coefficients (C_T):\n’);

disp(C_T);

fprintf(‘Power Coefficients (C_P):\n’);

disp(C_P);

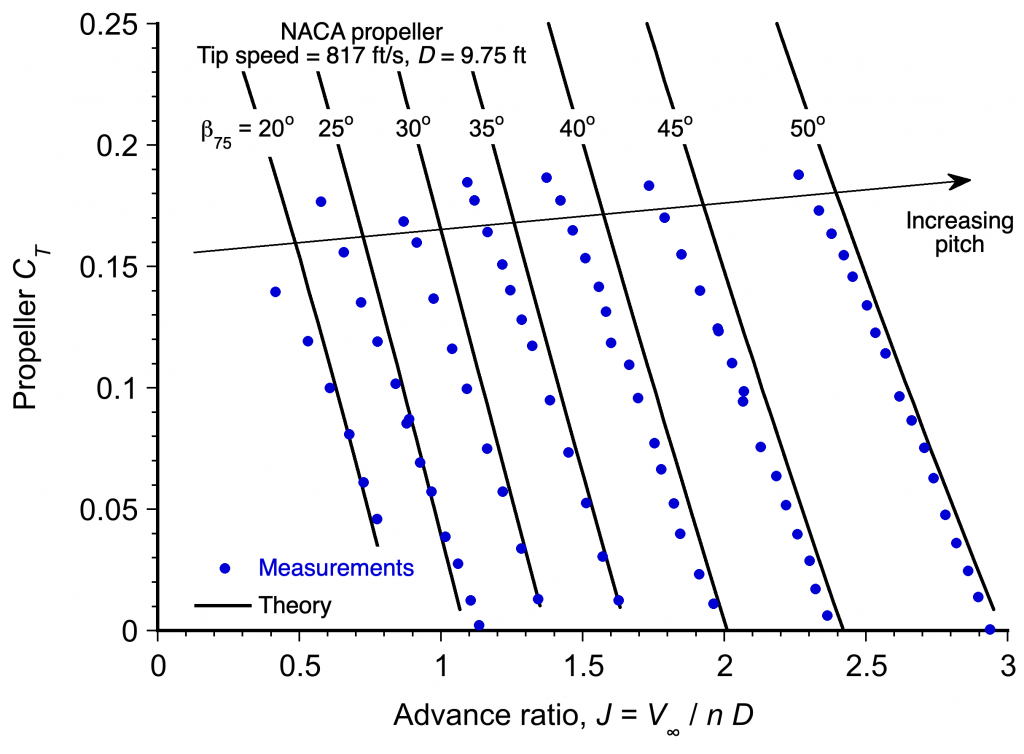

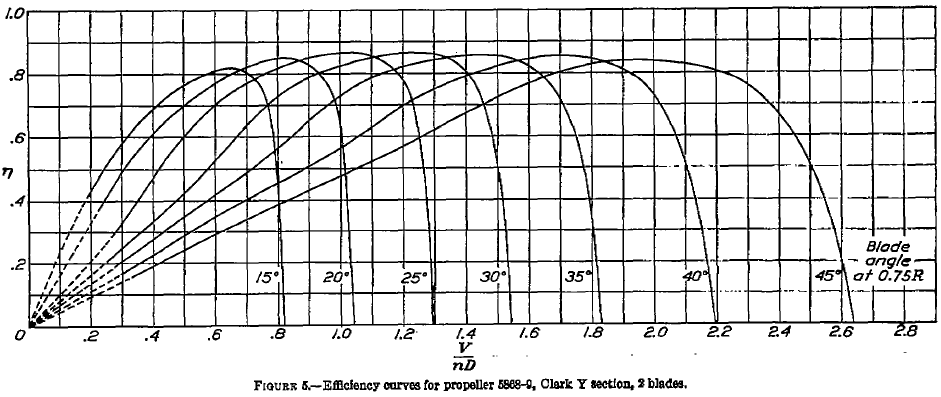

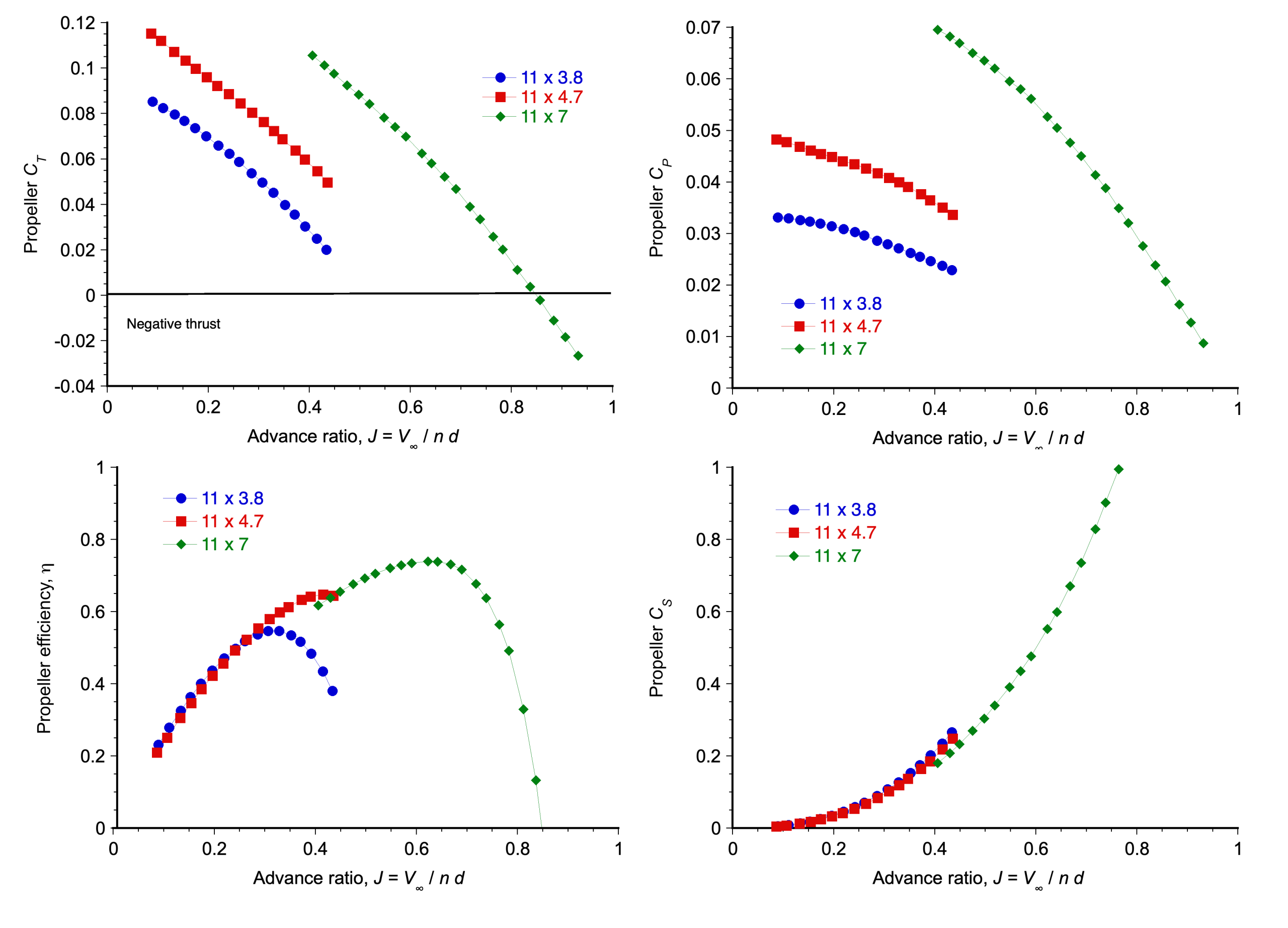

Propeller Performance Charts

Propeller performance curves are presented in terms of the thrust coefficient , power coefficient

, and propulsive efficiency

, respectively, analogous to how airfoil and wing aerodynamic coefficients are used.[11] All propellers have their characteristics quantified in this manner, and there is a separate set of curves for each reference blade pitch angle. By convention, the reference pitch angle

is not the angle of attack of the blade sections of the propeller but the reference pitch at the 75% blade span (i.e., at

), which is a geometric quantity and can be measured.

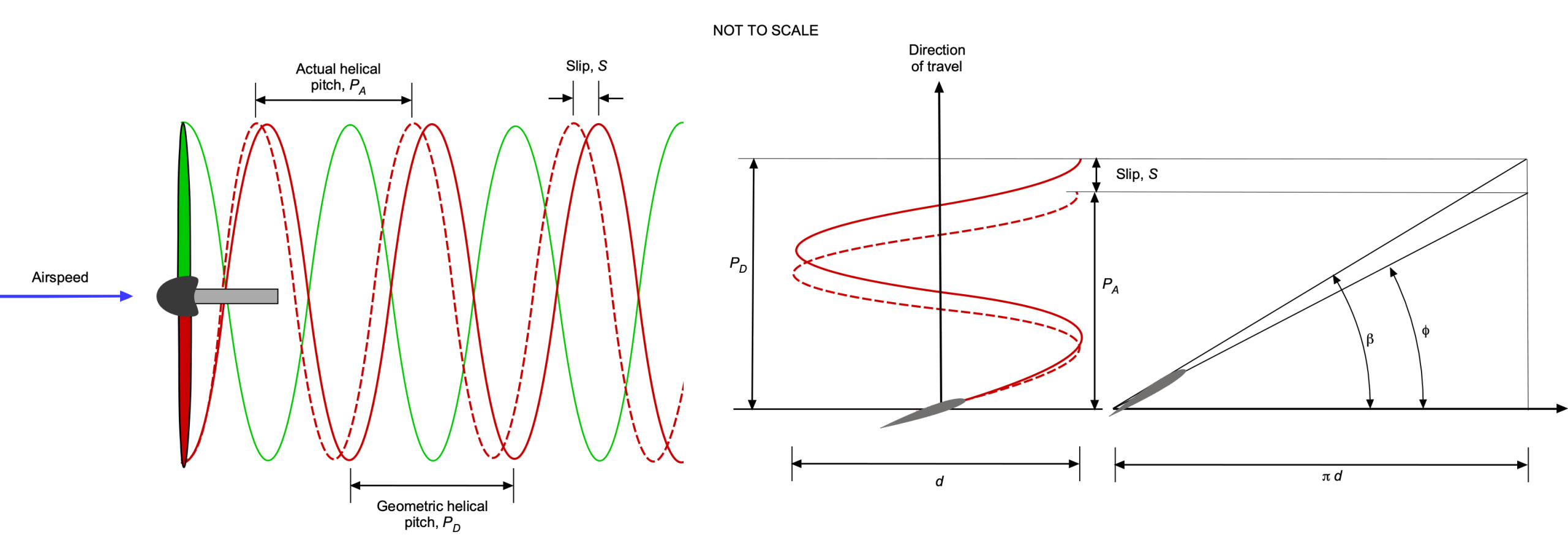

Helical Pitch and Slip

Often, the pitch of a propeller is measured in units of length rather than an angle. This refers to the geometric helical pitch traced by the reference blade section during one revolution, similar to a screw thread. Hence, the old name of a propeller is called an airscrew. As illustrated in the figure below, the helical pitch is the distance the propeller advances along its axis in one complete revolution, accounting for viscous effects. If the propeller were moving through a perfectly rigid medium (like a screw in a solid material), it would advance precisely the distance of its geometric pitch per revolution, as shown in the figure below. However, the propeller actually covers a shorter distance because the air deforms under its action, tracing out a helix with a lower pitch.

The helix angle, , describes the inclination of the path traced by a point on the propeller blade relative to the plane of rotation. A point on the propeller blade at radius

moves in a circular path with a circumferential distance per revolution given by

(78)

Simultaneously, the propeller advances axially by , which is given by

(79)

where is the airspeed and

is the rotational speed in revolutions per second. The helix angle

is given by

(80)

Substituting terms gives

(81)

For a reference span station, say , which is the conventional reference location for catalog data, the helix angle becomes

(82)

where is the propeller’s diameter.

A concept sometimes used to describe a propeller’s efficiency is slip, which quantifies the difference between the geometric pitch (theoretical advance per revolution) and the actual advance through the air. The propeller slip ratio, , is defined as

(83)

where is the geometric pitch, i.e., the distance the propeller would ideally move forward in one revolution, and

is the actual advance, i.e., the distance the propeller actually progresses through the air per revolution.

A high slip ratio indicates that the propeller is inefficient in converting rotational motion into forward thrust, whereas a low slip ratio (near zero) indicates more efficient operation. Ideally, the actual advance per revolution would equal the geometric pitch, but in practice, some slip is inevitable because of wake deformations that occur under the action of the propeller. While the slip ratio is sometimes used as an indicator of propeller performance, it has limited quantitative aerodynamic significance and should not be confused with propulsive efficiency.

Propeller Dimensions

Propeller dimensions are typically given in inches because of historical conventions in U.S. aviation, where USC units remain the industry standard for aircraft manufacturing and maintenance. This ensures consistency with aircraft manuals, FAA regulations, and existing designs, making it easier for pilots, mechanics, and manufacturers to communicate and compare specifications. Diameter and pitch are expressed in inches. For example, the Sensenich 69CK propeller has a 69-inch diameter and is available with helical pitch values ranging from 42 to 58 inches, offering options such as 69 x 42, 69 x 44, and so on. While metric conversions are used internationally, general aviation favors inches for compatibility and ease of use.

Advance Ratio

The propeller advance ratio, , is a fundamental aerodynamic parameter that helps determine a propeller’s efficiency and thrust production under different operating conditions. It connects forward motion, rotational speed, and propeller design, serving as a crucial non-dimensional parameter in propeller and rotor analysis. The advance ratio,

, is defined as

(84)

where is the airspeed (in units of m/s or ft/s),

is the rotational speed of the propeller (revolutions per second, fps), and

= diameter of the propeller (in units of m or ft). Physically, the advance ratio can be interpreted as the distance traveled by the propeller per revolution in terms of diameters, i.e., a non-dimensional distance or advance.

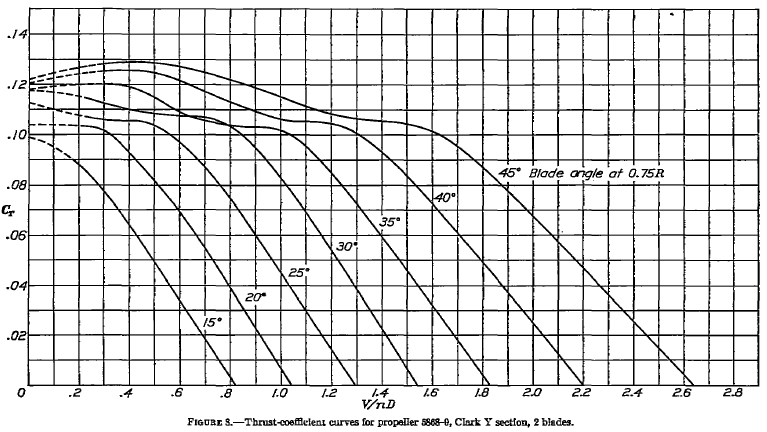

Thrust Coefficient

Recall that the thrust coefficient for a propeller is defined as

(85)

where is the thrust generated by the propeller,

is the propeller’s diameter, and

is the number of revolutions of the propeller per second. If the rotational angular velocity of the propeller is

, then

. Normally, the results for

and other propeller characteristics are plotted as a function of the advance ratio,

.

Representative versus

results for a propeller are shown in the figure below, with a separate curve for each reference blade pitch. Notice that the results from the blade element method discussed previously (i.e., the “theory”) agree well with the measurements.

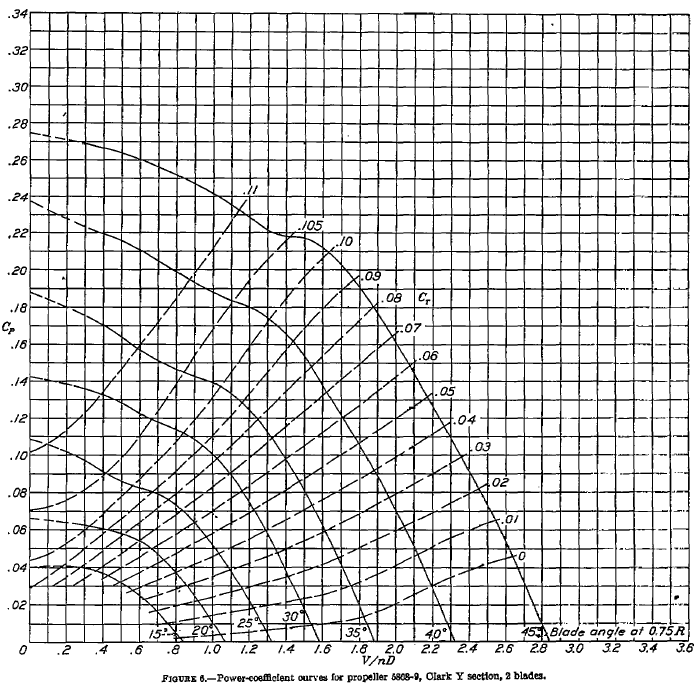

Power Coefficient

Recall that the corresponding power coefficient for the propeller is defined as

(86)

where would be the brake power, i.e., the power delivered to the propeller through the driving shaft. Normally, the torque,

, would be measured, so then

=

. The corresponding

versus

results for a propeller are shown in the figure below. Again, notice that the theory is in good agreement with the measurements.

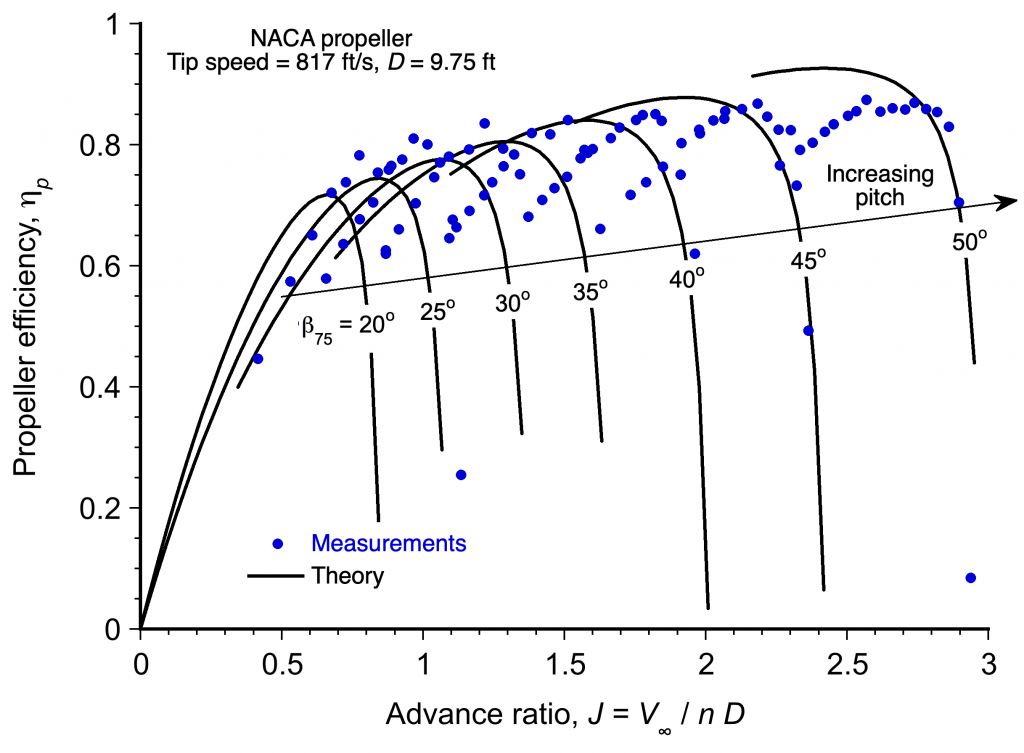

Propulsive Efficiency

Propeller efficiency measures how effectively the propeller converts available power into useful thrust. It is the ratio of useful power output (thrust power) to the total power input, i.e., engine power at the shaft or “brake” power. Propellers are typically designed for optimal performance at specific operating points. The propulsive efficiency of a propeller is defined as

(87)

which is just a non-dimensional statement that the propeller’s efficiency is the ratio of the useful power to the input power. Notice that the symbols or

are used to denote propeller efficiency, with

being preferred in most contexts to avoid confusion with the propulsion system’s overall efficiency.

Using the previous definitions of and

then

(88)

The corresponding representative versus

results for a propeller are shown in the figure below, again with one curve for each reference pitch angle.

Notice that for a given propeller operated with any given blade pitch and rotational speed

, its propulsive efficiency increases with increasing forward airspeed to reach a maximum and then diminishes rapidly. Consequently, a propeller of a given (fixed) blade pitch cannot operate with high propulsive efficiency over a wide range of values of

(or airspeed for a given rotational speed).

This latter outcome occurs because propeller blades are wings (rotating wings). All wings can only operate aerodynamically over relatively small ranges of the angle of attack, i.e., local blade section angles of attack between 2 and 14 degrees, depending on the local Mach number and Reynolds number. The local sectional angles of attack on the propeller depend not only on the rotational speed of the propeller and airspeed or advance ratio but also on how the propeller is twisted along its span. So, as airspeed changes, (propeller speed in terms of revolutions per second) is assumed constant. Then, the blade pitch must be increased to progressively maintain the angle of attack on the propeller. By gradually increasing the blade pitch, the best efficiency can be obtained over a much wider range of airspeeds, which is precisely the purpose of a continuously variable pitch or “constant speed” propeller.

Reference Blade Pitch

The reference geometric blade pitch angle of a propeller, often denoted , is measured at the section located at the 3/4 radius from the rotational axis, i.e., at

. The pitch angle is taken between the local chord line of that section and the plane of rotation. It should be noted that it is a purely geometric quantity and does not represent the aerodynamic angle of attack. At that station, a material point on the blade traces a helix whose geometric helical pitch is given by

(89)

Given a reported helical pitch value at 3/4 radius, the corresponding geometric pitch angle is

(90)

The significance of the 3/4-radius station lies in its use of blade-element theory. The power-weighted reference station is the radiuswise location at which an untwisted blade of constant angle

absorbs the same power as a hyperbolically twisted blade with

. Recall that the sectional velocity combines the rotational and axial components, i.e.,

(91)

where

(92)

Neglecting induced inflow corresponds to , so that

. The elemental torque is then

(93)

with

(94)

For small inflow angles, and

. Under an equal-thrust comparison, the induced torque satisfies

and cancels, so the profile torque provides the radiuswise weighting

.

For a blade with uniform chord with no root cutout, the power-weighted station is

(95)

Substituting gives the numerator as

(96)

and the denominator as

(97)

Forming the ratio and cancelling gives

(98)

In the small-inflow limit , then

(99)

which places the reference station at three-quarters radius. Increasing airspeed (larger ) moves the station slightly further inboard according to the closed-form expression above, but it remains close to

, which is why this location is used as a fixed reference. Once

is determined, the geometric helical pitch of the propeller can be reported as

(100)

Further Discussion of Propeller Performance

With this understanding of the flow at the blade section and the creation of thrust from the propeller, the various curves of ,

, and

, as shown previously, can now be explained in greater detail. At low values of

, the corresponding angles of attack of the blade sections are relatively high. So, the blade sections produce relatively high lift but are close to the point of stall. The propeller still produces thrust but requires high power and is inefficient. As airspeed and

increase, the blade sections operate at lower angles of attack and closer to their best section lift-to-drag ratios. As a result, thrust is maintained while drag on the blades decreases, leading to a significant increase in propulsive efficiency.

The lowest angles of attack will produce little lift on the blades or thrust on the propeller. However, there is a range of airspeeds (assuming blade pitch does not change) for which good propulsive efficiency is obtained. Therefore, the best aerodynamic efficiencies will only be obtained when all or most blade sections operate at or near the angles of attack that yield their best lift-to-drag ratio, which is typically between 2 and 8 degrees, depending on the incident Mach number.

There is eventually a point at higher airspeeds (or high ) where the blade sections encounter diminished angles of attack and higher helical Mach numbers, simultaneously decreasing thrust and efficiency unless the blade pitch increases further. Eventually, the blade pitch cannot be mechanically increased to improve efficiency, so efficiency decreases.

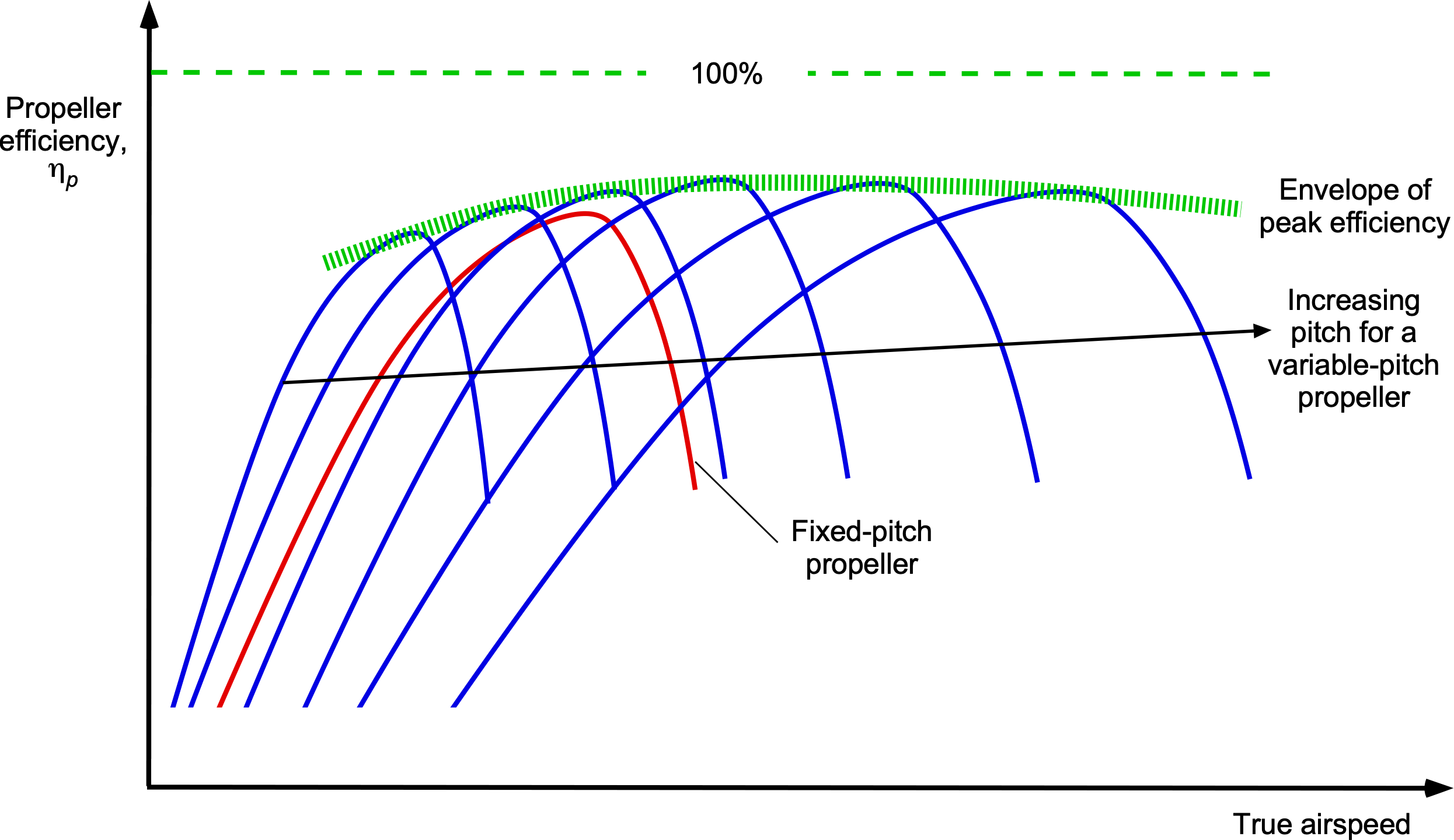

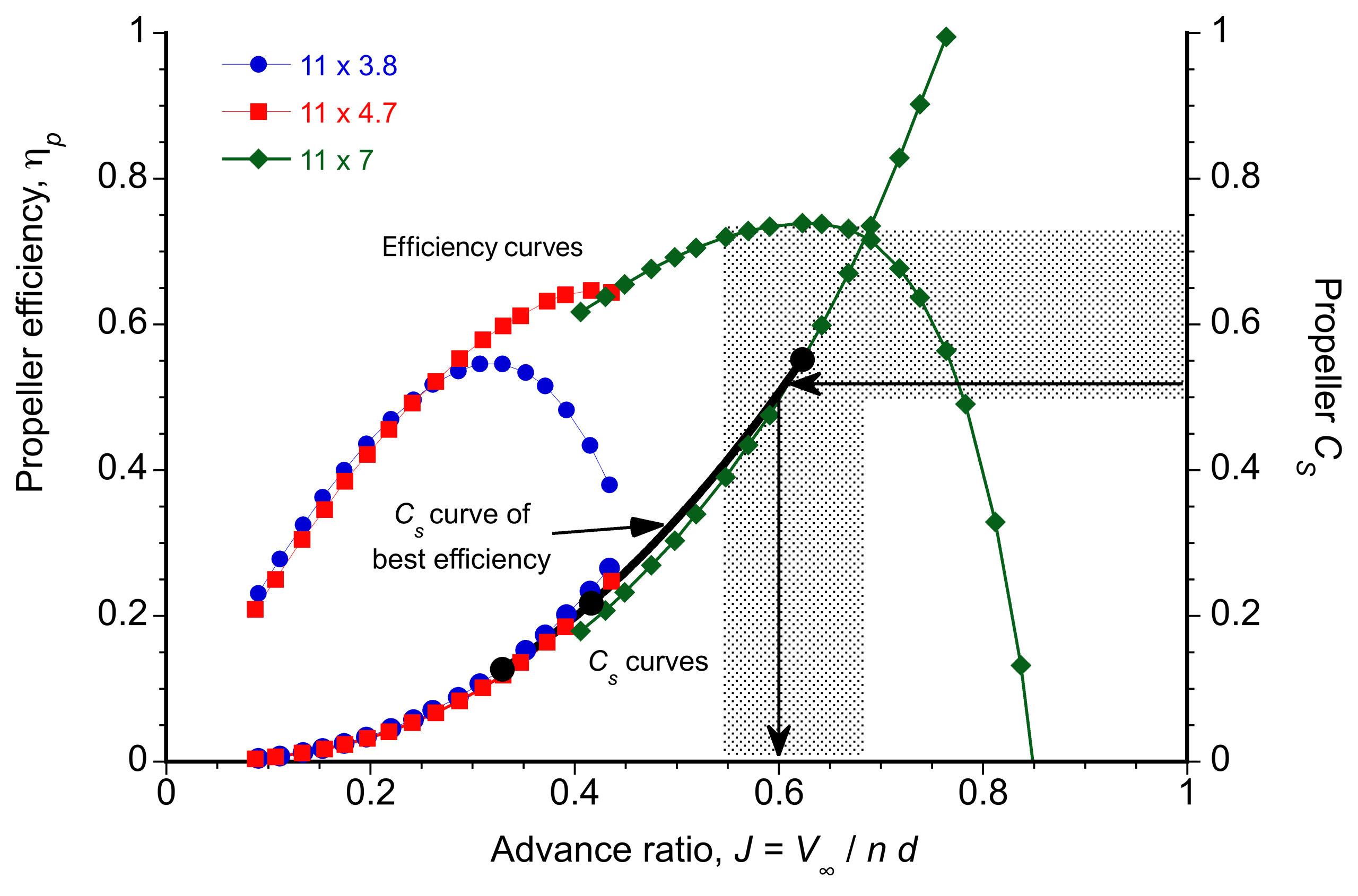

Propulsive Efficiency

The results also explain the differences in propulsive efficiency of fixed-pitch versus constant-speed propellers, as shown in the figure below. Notice that if the propeller pitch is fixed, its propulsive efficiency increases slowly with airspeed, reaches a maximum, and then decreases rapidly. The relatively low efficiency of a fixed-pitch propeller at low airspeeds results in poor takeoff and climb performance for the aircraft. Further increases in airspeed beyond the airspeed for peak efficiency will cause propeller efficiency to decrease precipitously. This behavior reduces the power delivered to the airstream as useful work, effectively setting an upper barrier to the airspeed achievable by the airplane.

The preceding situation is very different for a variable-pitch or constant-speed propeller, which can be set to a fine pitch for takeoff. This provides good propulsive efficiency and low airspeed, resulting in markedly better takeoff and climb performance for the airplane. As airspeed increases, the blade pitch can be adjusted to maintain a constant rpm schedule, allowing the propeller efficiency to closely track the peak efficiency envelope. This reason is why airplanes with constant-speed propellers have much better overall flight performance and can cruise at much higher airspeeds, as shown in the figure below. A constant-speed propeller also maintains a steady load on the engine, which is essential for long engine life.

Worked Example #1 – Calculating propeller performance

Refer to the propeller charts below, which are a standard performance presentation for all propellers. Assume that an actual propeller has a diameter of 7 ft and is a constant-speed propeller with a rotational speed of 2,000 rpm. The propeller operates at an equivalent density altitude of 8,000 ft ISA.

For each blade pitch angle measured at 75% radius and at the point of maximum propulsive efficiency in each case, estimate the following:

For each blade pitch angle measured at 75% radius and at the point of maximum propulsive efficiency in each case, estimate the following:

(a) What are the advance ratio values and corresponding airspeed values?

(b) What are the propeller thrust coefficient values and the propeller’s corresponding thrust?

(c) What are the values of the propeller power coefficient and the corresponding shaft torque and power required to rotate the propeller?

Show solution/hide solution.

(a) At the peak efficiency, the values of the advance ratio can be read off the first chart. We can easily do this to two decimal places; the chart can be digitized for better accuracy. We are also given information about the specific propeller, which is relatively small and would likely be for a general aviation aircraft, so in each case, we can calculate the corresponding airspeed for a given value of , i.e.,

so

It is best to use a table to show the results, i.e.,

| Blade pitch ( |

|||

| 15 | 0.82 | 0.65 | 151.7 |

| 20 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 191.3 |

| 25 | 0.87 | 1.04 | 242.7 |

| 30 | 0.87 | 1.25 | 292.7 |

| 35 | 0.86 | 1.45 | 338.3 |

| 40 | 0.86 | 1.70 | 398.7 |

| 45 | 0.84 | 1.95 | 455.0 |

(b) The propeller thrust coefficient can be read off the second chart for each value of the advance ratio, as was identified in the previous part. The thrust coefficient for a propeller is defined as

so the corresponding thrust (in units of force) from the propeller is

We are told that the propeller operates at an equivalent density altitude of 8,000 ft ISA. According to the ISA equations, the density at this altitude is 0.001869 slugs/ft. Inserting the information gives

Again, it is best to use a table to show the results, i.e.,

| Blade pitch ( |

|||

| 15 | 0.65 | 0.025 | 124.7 |

| 20 | 0.82 | 0.038 | 189.5 |

| 25 | 1.04 | 0.040 | 199.4 |

| 30 | 1.25 | 0.047 | 234.4 |

| 35 | 1.45 | 0.052 | 259.3 |

| 40 | 1.70 | 0.060 | 299.2 |

| 45 | 1.95 | 0.072 | 359.0 |

(c) The propeller power coefficient can be read off the third chart for each value of the advance ratio identified in the previous part. The power coefficient for a propeller is defined as

so the corresponding power needed to drive the propeller is

Inserting the known information gives

where the conversion to horsepower (hp) is obtained by dividing the result in ft-lb s by 550. Again, it is best to use a table to show the results, i.e.,

| Blade pitch ( |

|||

| 15 | 0.65 | 0.022 | 46.5 |

| 20 | 0.82 | 0.035 | 74.0 |

| 25 | 1.04 | 0.048 | 101.3 |

| 30 | 1.25 | 0.065 | 137.5 |

| 35 | 1.45 | 0.09 | 190.3 |

| 40 | 1.70 | 0.12 | 253.8 |

| 45 | 1.95 | 0.17 | 359.7 |

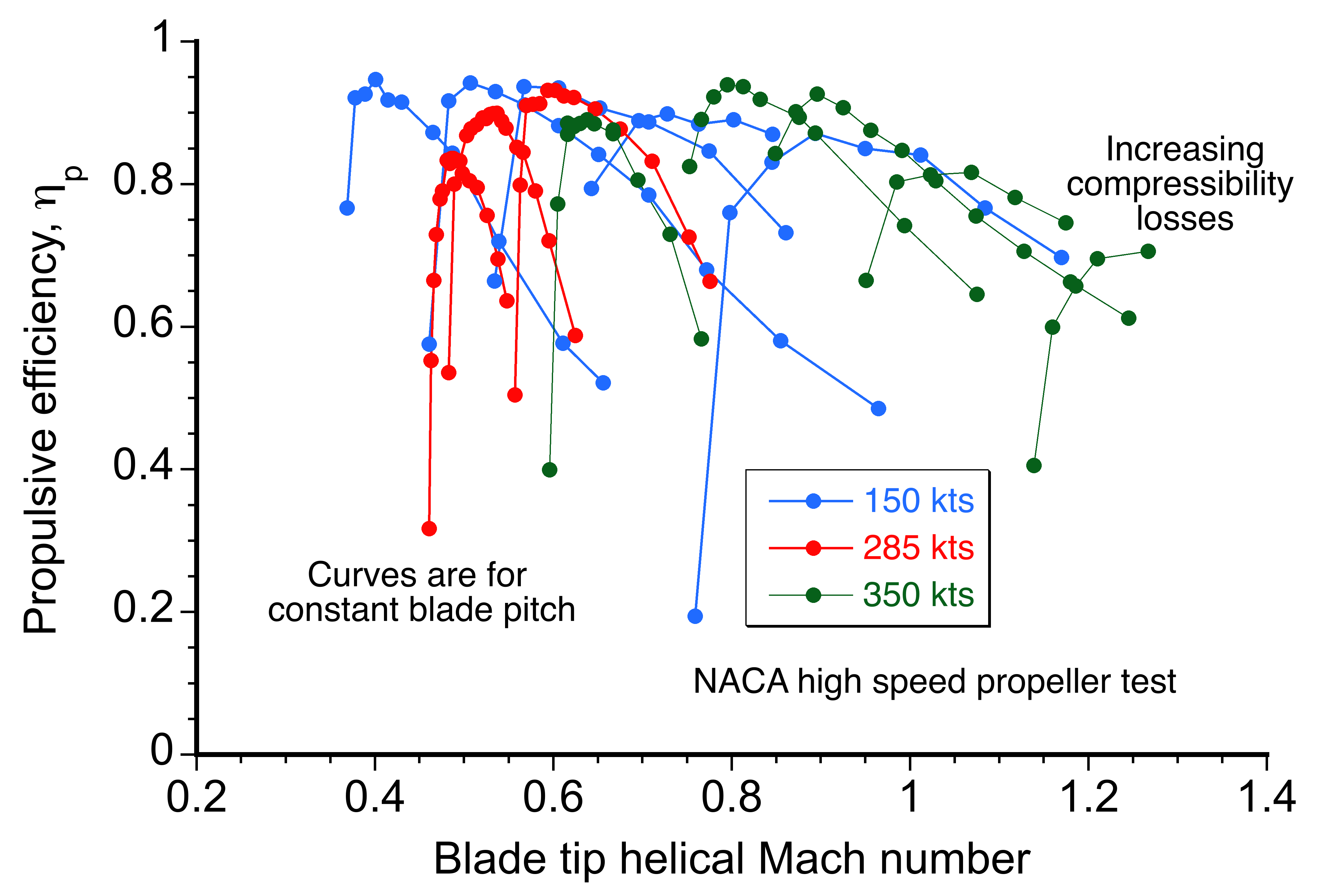

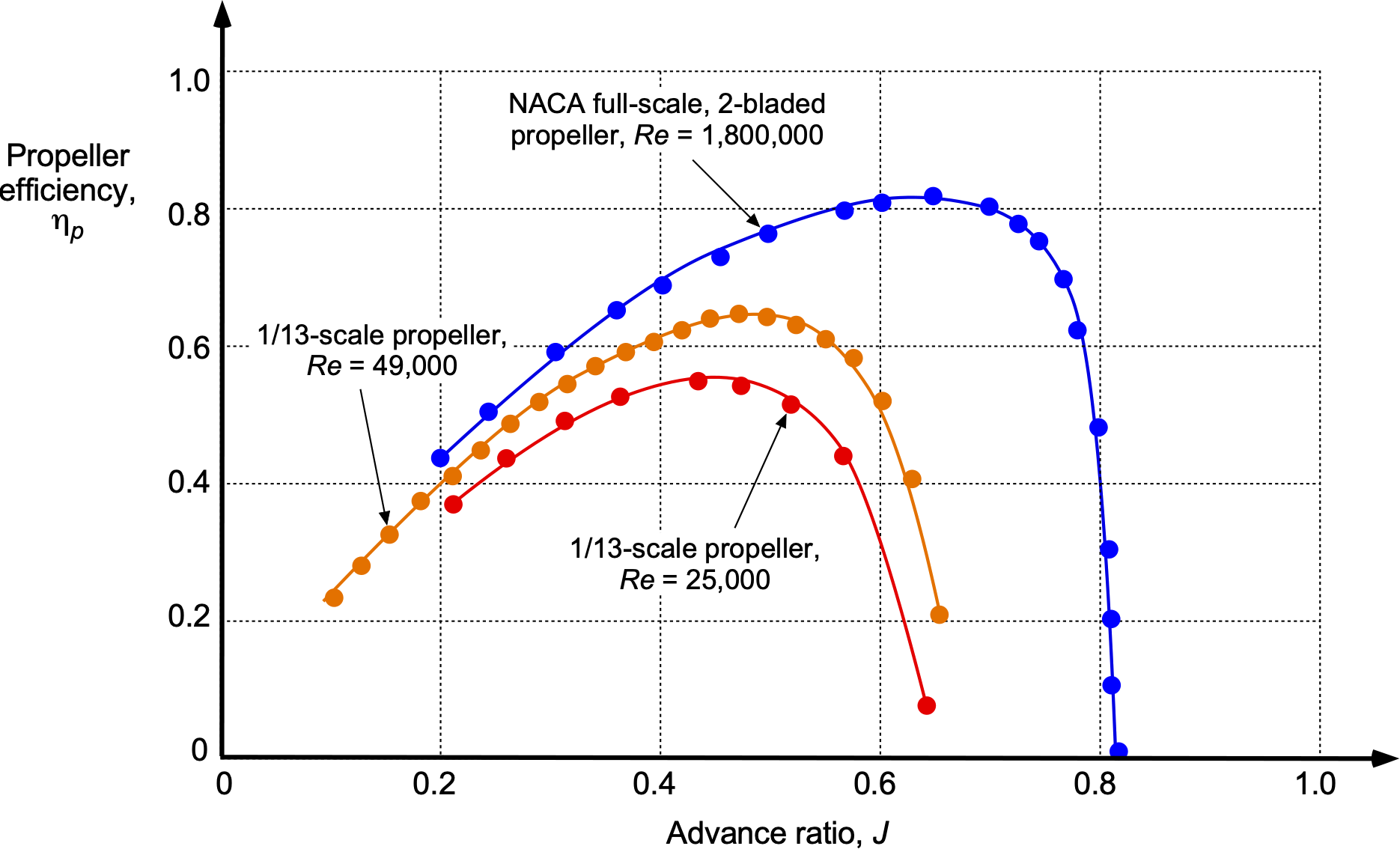

Helical Tip Mach Number

As airspeed and the values of increase, a concern is that the tip speed of the propeller can approach supersonic conditions. If this condition occurs, the propeller loses propulsive efficiency and produces more noise. This reduction in efficiency means that more power is required to make the same amount of thrust, which can adversely affect fuel consumption and overall flight performance. Supersonic airflow generates shock waves, resulting in a dramatic increase in propeller noise. A propeller’s noise is a significant concern in aviation, impacting passenger comfort, community acceptance, and regulatory compliance.

Let be the helical tip velocity based on the vector sum of the rotational and airspeed components at the blade elements. Therefore, the rotational tip speed of a propeller characterized by radius

or diameter

(= 2

) is

(101)

and so the helical tip speed of the propeller is

(102)

where is the forward airspeed. Therefore, the helical Mach number

will be

(103)

where is the speed of sound at the atmospheric conditions at which the propeller operates.

The measurements shown in the figure below, for a high-speed NACA propeller with thin blades, eventually reach supersonic helical-tip Mach numbers. In this case, the measurements were taken at a constant blade pitch to examine variations in rotational speed. Notice that rapid losses in propulsive efficiency (from a peak of about 0.95) are produced at higher airspeeds if the rotational tip speeds are kept at high values. Compressibility losses increase when the helical tip Mach number reaches about 0.8. While every propeller will be different, exceeding some limiting critical tip Mach number at the blade tip, which may be around 0.7 for a standard blade and 0.8 for a thin airfoil section and swept leading edge at the tip, can be expected to decrease propulsive efficiency, increase noise, or, more usually, both.

Propeller Noise

Propeller noise is a significant contributor to the acoustic signature of propeller-driven aircraft, particularly during takeoff, climb, and high-speed cruise flight. It originates from unsteady aerodynamic forces acting on the blades and from compressibility effects at high tip speeds. Unlike rotorcraft, conventional single-rotor airplane propellers do not experience blade-wake or blade-vortex interaction noise. Instead, the dominant sources are thickness noise, loading noise, compressibility noise, and shock waves originating at the blade tips.

Thickness noise arises from the periodic displacement of air by the rotating blades. This type of noise radiates at the blade-passing frequency and integer multiples of its harmonics. Aerodynamic forces generate loading noise, primarily from blade lift. It is most intense during high-thrust phases such as takeoff and climb. Both sources contribute to the prominent tonal peaks in the noise spectrum.

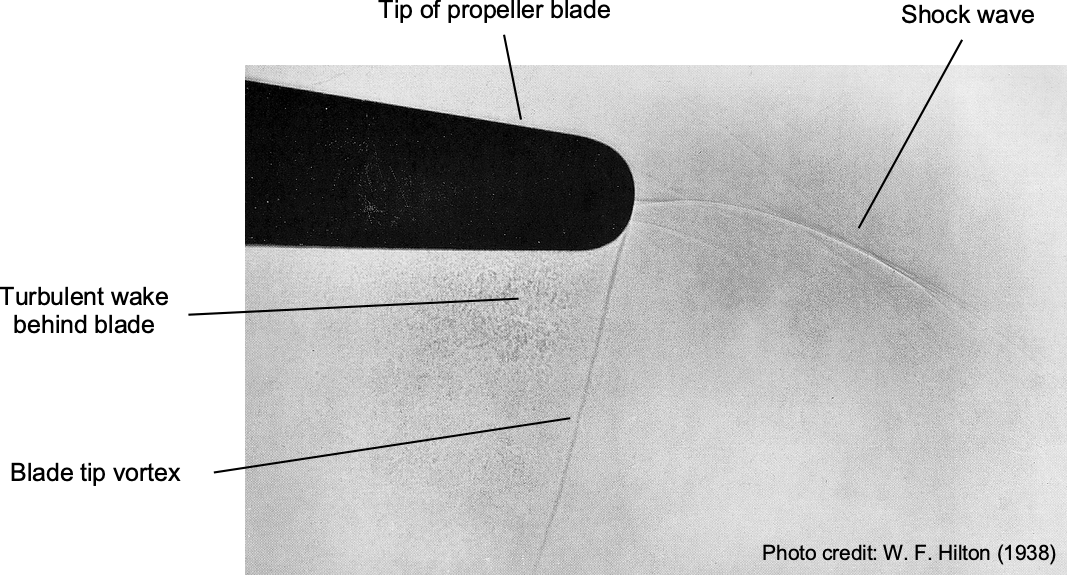

As the tip Mach number approaches or exceeds 0.85, compressibility effects become significant, and localized shock waves may form near the blade tips. This results in a significant increase in noise amplitude, harshness, and high-frequency content. The noise becomes impulsive in character and highly directional. The schlieren image below illustrates this phenomenon for , showing spiraling acoustic Mach waves forming at the blade tips. These waves compress and intertwine into a rotating analog of a Mach cone produced by an airplane flying near the speed of sound, similar in character to a forming sonic boom. Also visible are the tip vortex and the turbulent blade wake, which contribute additional high-frequency acoustic content.

The dominant source of propeller noise in airplane applications is loading or monopole noise, generated by unsteady aerodynamic forces acting on the rotating blades. These effects can be modeled as a dipole source, and the far-field acoustic power radiated by such a source increases rapidly with blade tip speed. From classical aeroacoustic theory, the acoustic power radiated by a rotating blade system can be approximated as

(104)

where is the radiated acoustic power,

is the freestream air density,

is the aerodynamic force on the blade,

is the angular velocity of the propeller,

is the blade radius, and

is the freestream speed of sound. The aerodynamic force scales with dynamic pressure, giving

. Therefore, substituting into the expression for

leads to

(105)

Furthermore, using the rotational tip Mach number gives

(106)

Because the sound pressure level (SPL) scales logarithmically with acoustic power, then

(107)

and finally leading to the propeller noise scaling law with tip Mach number, i.e., the sound pressure level is

(108)

In practice, empirical measurements often yield a slightly lower exponent due to effects other than ideal conditions, such as non-uniform inflow, installation interference, and atmospheric absorption. A more commonly used representation is

(109)

The dominant frequency of propeller noise corresponds to the blade-passing frequency, defined as

(110)

where is the number of blades and

is the shaft rotational frequency. Tonal components, associated with thickness and loading noise, tend to dominate the acoustic spectrum and are most intense at the blade-passing frequency and its harmonics. Broadband noise arises from turbulence ingestion, unsteady blade loading, and distorted inflow conditions. The radiation pattern is highly directional, with tonal noise being strongest in the plane of rotation, while loading noise is primarily radiated in a direction parallel to the thrust axis.

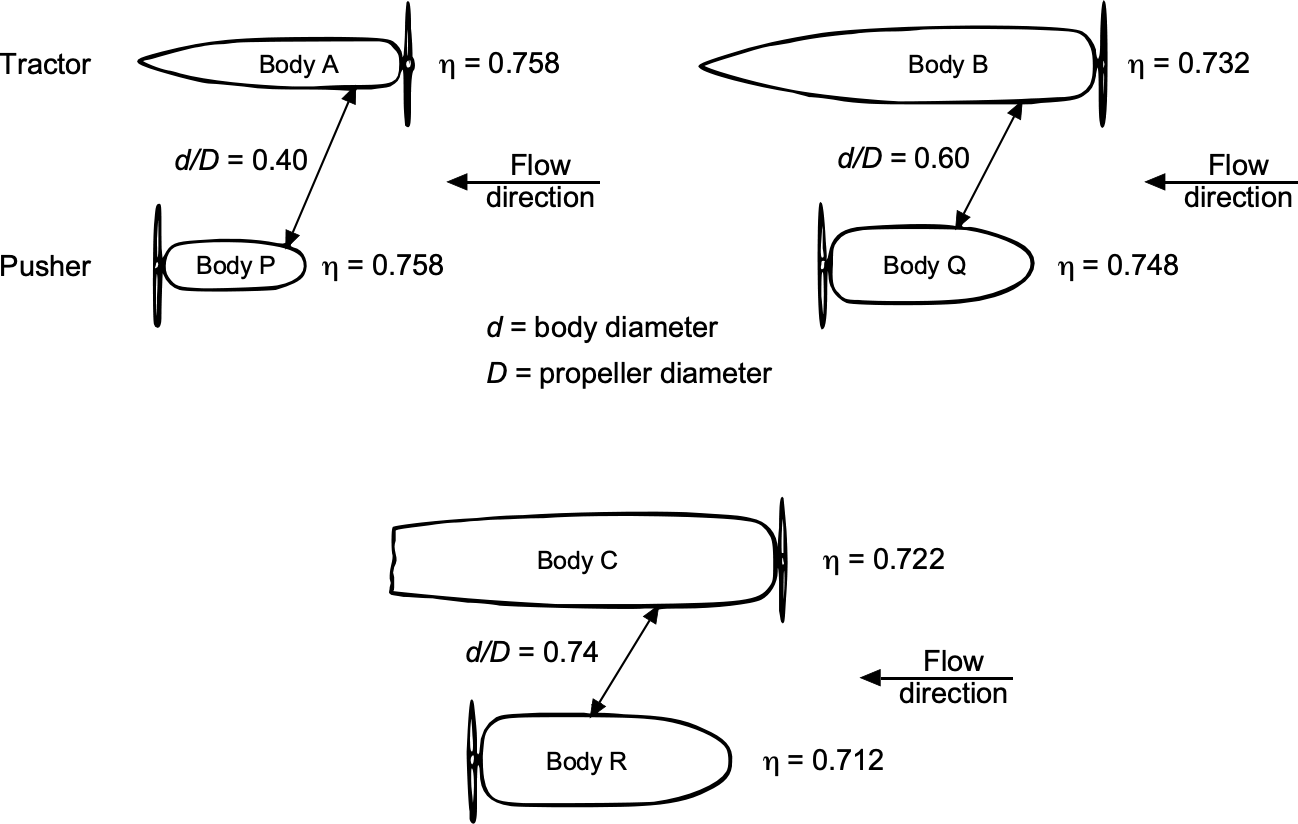

Several strategies exist to reduce propeller noise. Limiting tip speed is essential to avoid shock-induced impulsive noise, which can be managed by selecting a larger diameter or reducing the rotational speed. Increasing the number of blades reduces the per-blade loading and shifts tonal energy to higher, more attenuated frequencies. Careful blade design, including sweep, twist, and taper, helps minimize unsteady aerodynamic forces and delay the onset of compressibility effects. Finally, installation effects are critical; distorted inflow caused by fuselage or wing boundary layers can exacerbate noise, especially in pusher configurations. Tractor propeller arrangements, with cleaner inflow conditions, typically offer lower noise levels for a given thrust.

Example #2 – Calculating a propeller’s helical tip Mach number

Refer back to Worked Example #1. What are the propeller’s helical tip speed values and helical Mach number? Comment on your results. Note: The helical tip speed is the vector sum of the rotational speed at the tip of the propeller and the freestream (airspeed).

Show solution/hide solution.

Let be the helical tip velocity based on the vector sum of the rotational and airspeed components. The rotational tip speed of a propeller of diameter

is

where and so the helical tip speed of the propeller is

where is the forward airspeed. The helical Mach number

will be

where is the local speed of sound at the conditions at which the propeller operates. At 8,000 ft ISA density altitude,

1085.3 ft/s.As a final table to show the results, the helical tip speed and Mach number are:

| Blade pitch ( |

||||

| 15 | 0.65 | 151.7 | 748.6 | 0.69 |

| 20 | 0.82 | 191.3 | 757.6 | 0.70 |

| 25 | 1.04 | 242.7 | 772.2 | 0.71 |

| 30 | 1.25 | 292.7 | 788.9 | 0.73 |

| 35 | 1.45 | 338.3 | 807.3 | 0.74 |

| 40 | 1.70 | 398.7 | 833.5 | 0.77 |

| 45 | 1.95 | 455.0 | 862.8 | 0.79 |

We notice that for an airspeed above 400 ft/s, the propeller blade tips would likely begin to operate near or just beyond the critical Mach number (i.e., the onset of transonic flow), which for the thin tips of propeller blades is about 0.8. Under these conditions, the propeller will likely lose propulsive efficiency.

Propeller Selection Process

Propeller selection must match the aircraft’s mission, performance goals, and propulsion system. Key factors include thrust requirements across flight phases, powerplant type (piston, turboprop, or electric), cruise efficiency, and installation constraints. The propeller diameter has a significant impact on thrust, power consumption, and efficiency. Larger diameters enhance low-speed performance but may be limited by ground clearance, airframe geometry, or high tip speeds. At higher rpm, blade tips must remain subsonic to avoid compressibility losses and the rapid increase in noise associated with the tip Mach number.

The blade count affects the amount of thrust a propeller can produce for a given diameter. More blades allow the disk to absorb greater power, which is helpful for high-power engines or when the diameter is constrained by ground clearance or airframe layout. However, additional blades add weight, drag, and mechanical complexity, especially in variable-pitch systems. Blade geometry must also be optimized spanwise to maintain efficiency across varying inflow conditions. Key factors include the airfoil section, chord distribution, and twist, which typically follow a hyperbolic pattern from the root to the tip.

Variable-pitch or constant-speed propellers maintain propulsive efficiency by adjusting blade angles in flight and are standard on high-performance piston and turboprop aircraft. Material selection also matters. Wood is lightweight and inexpensive, but it is limited to low-power use under 200 shp (149.4 kW). In contrast, aluminum is at least three times stronger but approximately six times heavier by volume. Composite blades combine low weight with high strength, allowing for thinner, more efficient shapes in high-speed turboprop applications.

The propeller must also match the engine’s power and torque characteristics. Piston engines operate efficiently at lower rpm (less than 3,000) and can often drive propellers directly. Turboshaft engines typically require a reduction gearbox, although free-turbine designs are also common and efficient.[12] Electric motors, with high torque at low rpm, can also drive large, slow-turning propellers directly, in the range 4,000 to 8,000 rpm. Additional concerns for propeller integration include vibration, noise, and inflow distortion, particularly in pusher configurations affected by an upstream wake. A successful design will strike a balance among these factors to deliver efficient, reliable, and quiet propulsion that suits the aircraft and its mission.

Steps for Propeller Selection

The following are the specific steps that are involved in the selection of a propeller:

- Define the mission profile and flight envelope. These requirements may include the maximum takeoff weight, cruise speed and altitude, climb performance, and powerplant characteristics and limitations such as available power and allowable rotational speed (rpm) range. Airframe installation constraints, such as ground clearance or nacelle position, must also be considered.

- Estimate thrust and power requirements. Use aircraft drag estimates and mission analysis to determine the required thrust during takeoff, climb, and cruise. Combine this with available shaft power from the powerplant to calculate the required propeller efficiency.

- Select a candidate propeller diameter and rotational speed. Select a diameter that provides sufficient disk area for thrust without exceeding the tip Mach number limit of approximately 0.85 at the maximum propeller rpm, thereby minimizing compressibility losses.

- Choose or design a blade geometry. For custom designs, one can use blade-element theory (BET) or similar methods to determine the optimal twist and planform (chord) distributions. For off-the-shelf options, consult the manufacturer’s data sheets and performance characteristics (e.g.,

curves) to determine the thrust coefficient, power coefficient, and efficiency, which will help select the propeller.

- Calculate the advance ratio and match it to the performance requirements. Use the

parameter to find the operating point of the aircraft, then compare it to the propeller performance curves. One generally aims to operate the propeller near its peak efficiency at cruise, while still ensuring sufficient thrust and propulsive efficiency at lower airspeeds, such as takeoff.

- Determine whether variable pitch is required. If the flight conditions span a wide range of flight speeds or power settings, a variable-pitch propeller may be needed to maintain the propulsive efficiency. Fixed-pitch or ground-adjustable designs are simpler but can be optimized for only one flight condition.

- Evaluate structural and material choices. Consider blade loads, centrifugal forces, vibration, and the possibilities of material fatigue. Common materials include wood, aluminum, and composite, each with its own trade-offs in terms of weight, strength, durability, and cost.

- Integrate with the engine and airframe. Ensure compatibility with the engine’s torque curve and power output. It may be necessary to account for airframe-induced inflow distortion, especially in pusher configurations. Validate hub mounting, spinner clearance, and “ram” airflow to the cooling system.

- Test and refine the selection. After the preliminary design or selection, the propeller’s performance must be verified through ground runs and flight testing. Normally, aircraft manufacturers instrument the powerplant and aircraft to record enough parameters to verify or revise the prepropeller design as needed, based on flight test data.

Speed-Power Coefficient (Weick) Method

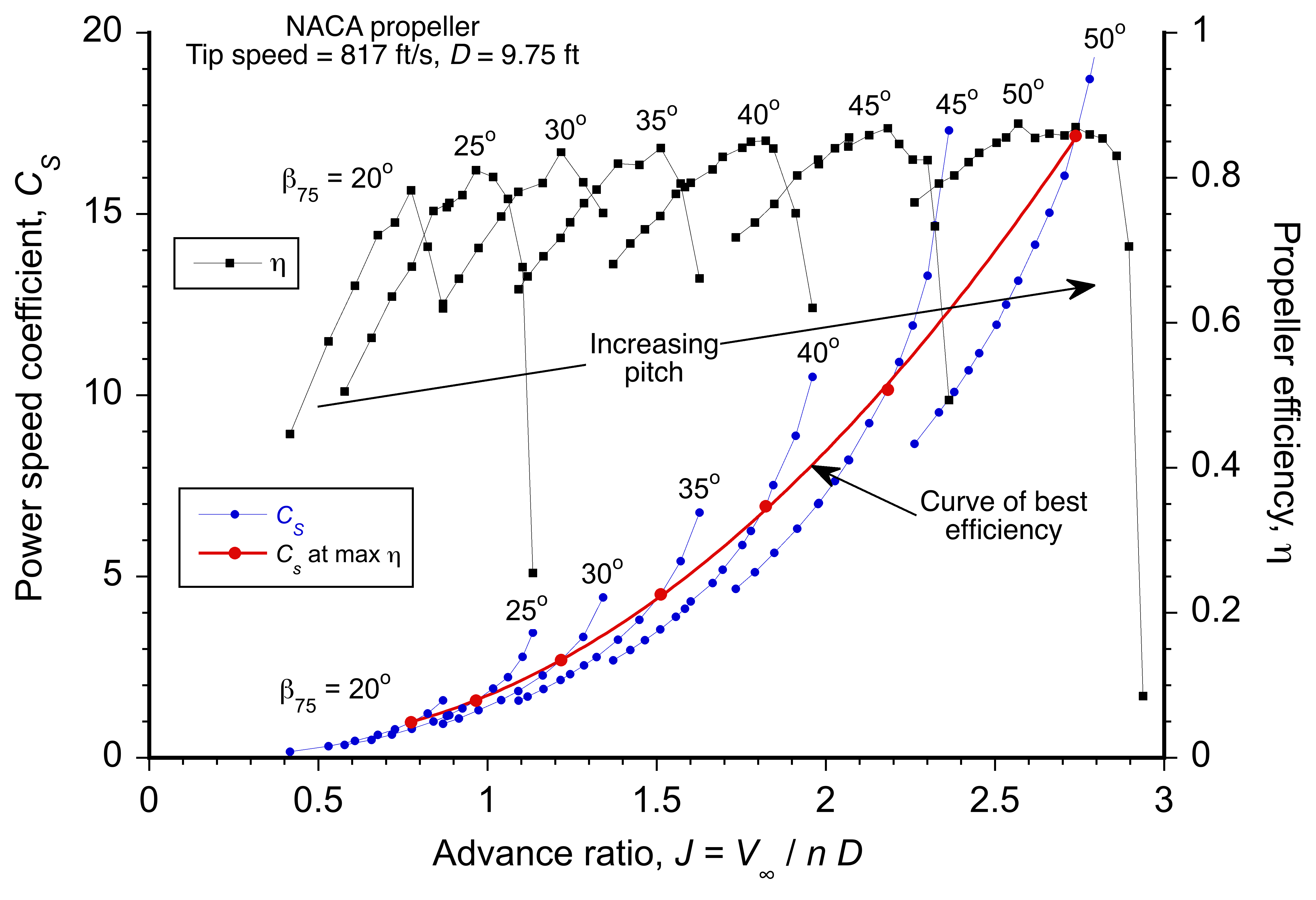

The speed-power coefficient, , is a non-dimensional parameter introduced by Fred Weick at NACA to characterize propeller performance independently of physical dimensions, such as diameter or blade pitch. Weick originally used the