31 Airfoil Shapes

Introduction

Aerospace engineers must know how to select or design suitable cross-sectional wing shapes, often called airfoil profiles or airfoils, for use on a diverse range of flight vehicles such as subsonic, transonic, and supersonic airplanes, space launch vehicles, as well as helicopter rotors, propeller blades, drones, and unoccupied aerial vehicles (UAVs), eVTOL concepts, etc. To this end, not all airfoils are created equal; different airfoil shapes are better suited to one application than another. For example, airfoils used on the wings of low-speed airplanes are generally thicker (in terms of thickness-to-chord ratio) and have greater camber. Airfoils for high-speed aircraft, especially those designed for supersonic flight, are significantly thinner, with more pointed leading edges and less camber.

Historically, the design of airfoil shapes for specific applications has evolved through a synergistic process that combines theoretical analysis, wind-tunnel testing, and flight testing. Today, engineers often begin by selecting candidate airfoil shapes with the desired characteristics and then employing mathematical models, perhaps even detailed Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations, to predict their aerodynamic performance. Measurements made in tunnels can validate these predictions, providing empirical data for any geometric design changes and aerodynamic refinements of the airfoil section. Subsequent flight testing may further validate the selected airfoil(s), enabling engineers to iteratively refine airfoil designs based on measured aircraft performance. Throughout this process, considerations specific to the intended application must be integrated to ensure that the optimized airfoil shapes meet the aerodynamic and performance requirements of the particular aircraft or other flight vehicle.

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the historical evolution of airfoil sections for aircraft applications.

- Identify and explain the significance of the critical geometric parameters that define the shape of an airfoil.

- Know how to construct a NACA airfoil profile geometrically using a camberline shape, thickness envelope, and nose radius.

- Understand the differences in the shapes between subsonic, transonic, and supersonic airfoil sections.

History of Airfoils

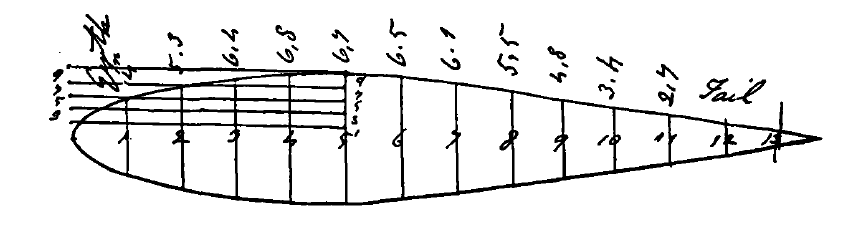

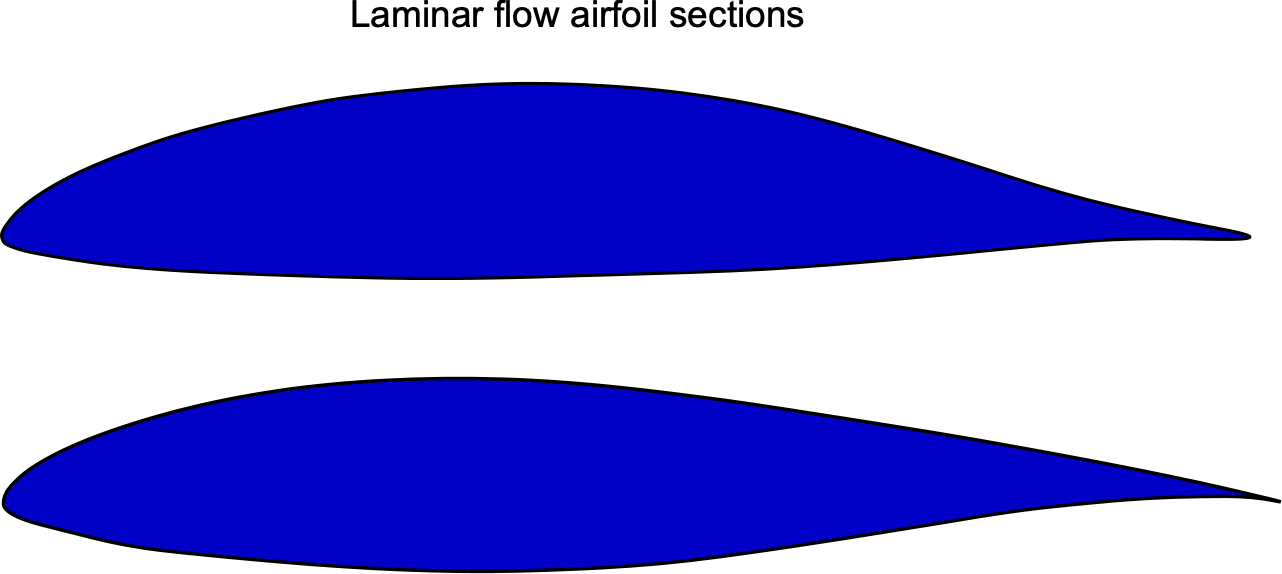

Historically, the most suitable airfoils for most practical engineering applications were obtained through an evolutionary process. In this regard, theory and experimentation (e.g., wind tunnel testing) have been used to design airfoils that meet specific operating requirements for different airplane types. George Cayley, often revered as the “Father of Aeronautics,” delineated the problem of sustentation, i.e., aerodynamic lift, from that of drag, i.e., the component of aerodynamic resistance. Cayley made essential observations about drag, including “It has been found by experiment that the shape of the hinder part of the spindle is of as much importance as that of the front in diminishing resistance.” Cayley referred to the shape of a wing as spindle-shaped and obtained the profile shown in the drawing below[1] by measuring the cross-sectional shape of a trout, which, interestingly enough, conforms closely to modern low-drag “laminar” airfoil sections.

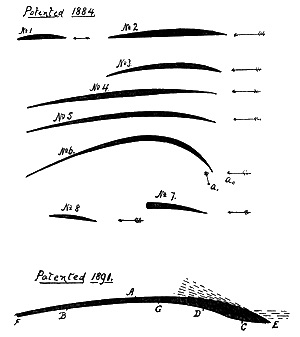

Some of the earliest known airfoil sections considered for aircraft concepts were patented in the 1880s by Horatio Phillips, as shown in the figure below, which were inspired by the cross-section of bird wings. Taking inspiration from nature is nothing new in engineering, but history shows that it should not necessarily be a basis for our engineering. Notice the thin, highly cambered profile shapes, which are now known to have poor aerodynamic efficiency compared to modern airfoils, at least under the operating conditions of most flight vehicles[2]. Phillips also tested these airfoils in one of the very first wind tunnels.

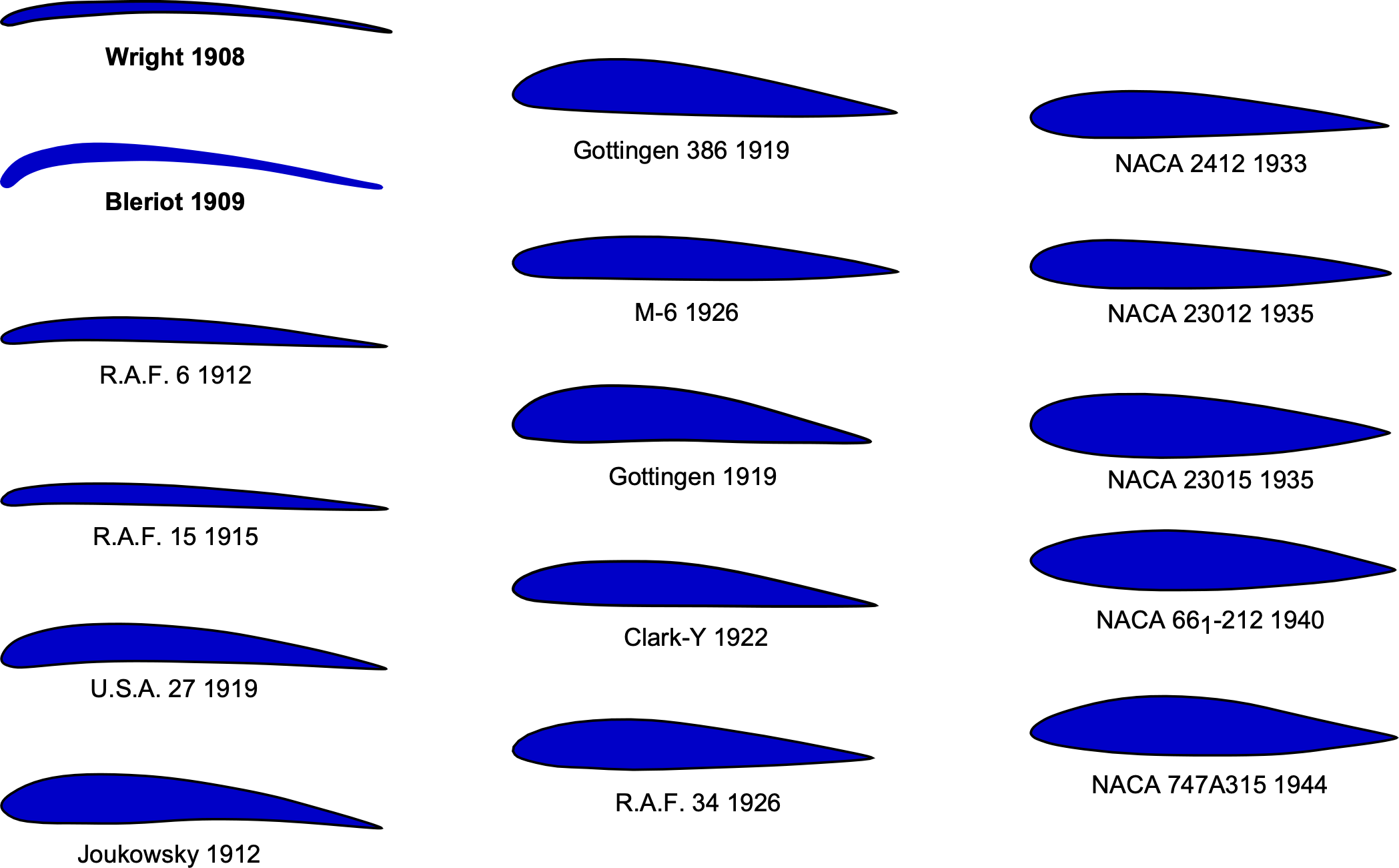

Gustave Eiffel conducted additional experiments using an open-return (single-passage) wind tunnel. The Wright brothers also built and used an open-return wind tunnel, which proved instrumental to the success of their 1903 Flyer. They recognized that not only was the airfoil cross-section important for wing efficiency, but also the wing span-to-chord ratio, known as the aspect ratio. The figure below illustrates the rapid evolution of airfoil shapes tailored for aircraft applications between 1908 and 1944, with the thin, highly cambered airfoil sections used on early airplanes soon being relegated to history.

Wind-tunnel work to measure airfoil characteristics was soon followed by the development of validated numerical methods to predict chordwise pressure distributions and airfoil characteristics, eliminating the need for as many wind-tunnel measurements. Computational tools for designing airfoils with specific aerodynamic characteristics first became available in the 1920s. The development of the thin-airfoil theory by Max Munk (in the U.S.) and Hermann Glauert (in the U.K.) during the 1920s led to a better understanding of how the camber affected an airfoil’s lift, drag, and pitching moment.

The problem of defining the airfoil pressure distribution for an airfoil with thickness and arbitrary shape was tackled by Theodorsen & Garrick in the early 1930s. The design of practical airfoil profiles was further aided by methods such as the conformal transformation, first developed by Prandtl & Tietjens. This latter approach enabled the computation of pressure distributions and the resulting lift and pitching moment characteristics of some specially shaped “Joukowsky” airfoils. The aerodynamic properties of Joukowsky airfoils were measured in wind tunnel tests starting in the late 1920s at the AVA in Göttingen, Germany, and by the NACA in the U.S. from 1930 onward.

Today, it is possible to predict the aerodynamic characteristics of airfoils with high confidence using popular computer codes, such as XFoil, which is widely available. Even today, however, measurements of airfoil characteristics in wind tunnels have proven more reliable than calculations, particularly at higher angles of attack, higher subsonic and transonic Mach numbers, or lower Reynolds numbers.

There are thousands of airfoils in current use, most of which have been selected or adapted to optimize performance for specific flight-vehicle applications. A common question is what airfoil section(s) are used on particular aircraft. Jane’s All The World’s Aircraft is a reliable source of information for civil aircraft, often requiring a visit to the university library’s reference section. A comprehensive online list of airplanes and the airfoil(s) that they use has also been prepared.

Design Requirements

Design requirements for airfoil sections are essential to ensure optimal performance in various applications such as aircraft wings, tail surfaces, and other aerodynamic surfaces. The specific design requirements may vary depending on the intended use and performance objectives, but here are some typical design considerations for airfoil sections:

- Obtaining high values of the maximum attainable lift coefficient before flow separation and stall occur.

- The minimization of drag over a broad range of operating conditions.

- The attainment of a particular value of nose-up or nose-down pitching moment.

- The ability to reach high values of the lift-to-drag ratio, perhaps also at specific angles of attack.

- A high critical Mach number, i.e., the freestream Mach number when supersonic flow first develops over the airfoil.

- Good lift-to-drag ratio in supersonic flight over a broad range of angles of attack.

There has recently been much interest in designing efficient airfoils for use at the very low flow speeds and low Reynolds numbers found on drones and UAV systems. These require detailed knowledge of boundary layer development, including the transition from laminar to turbulent boundary layers. Airfoil characteristics at low Reynolds numbers below 10 are usually quite different from those at higher Reynolds numbers above

, often showing remarkably poor aerodynamic efficiencies.

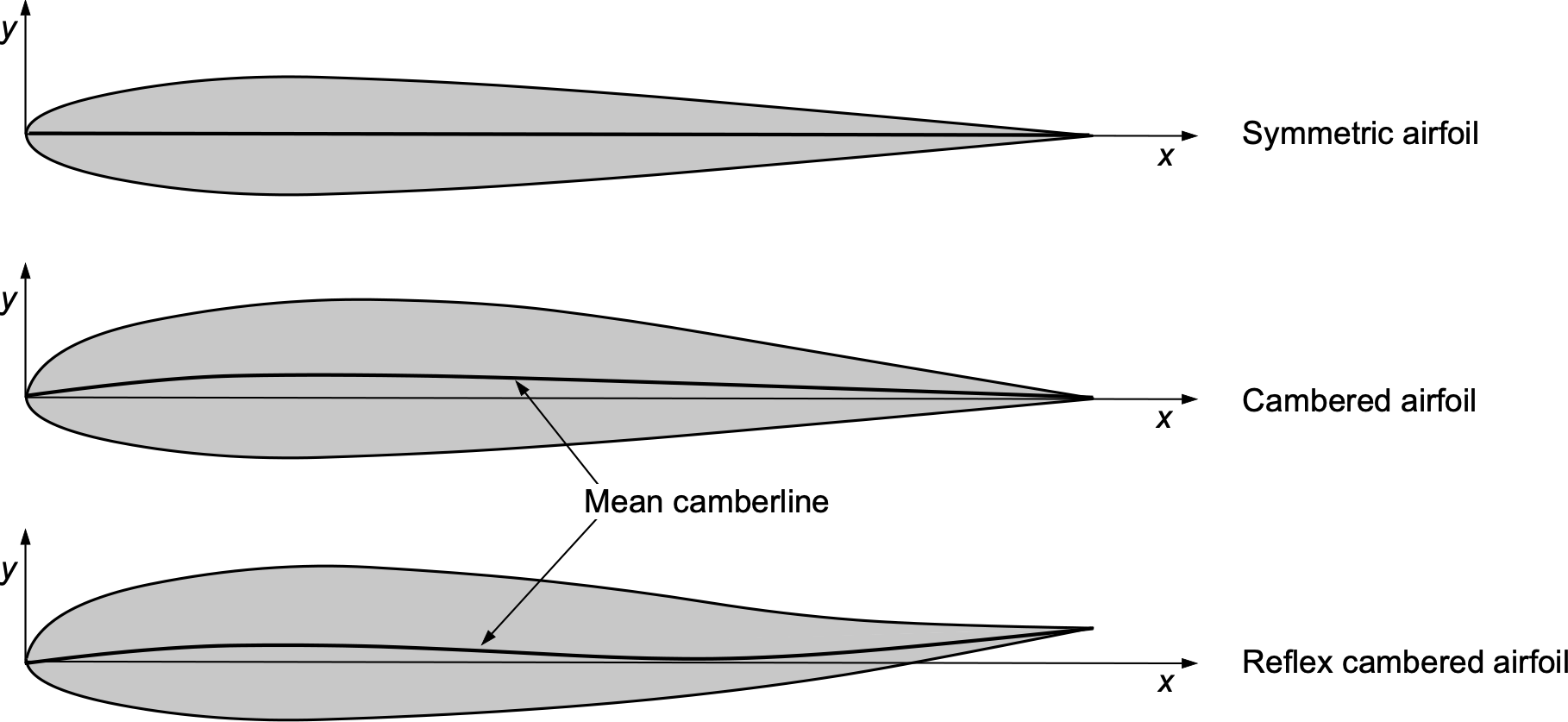

Airfoil Geometry

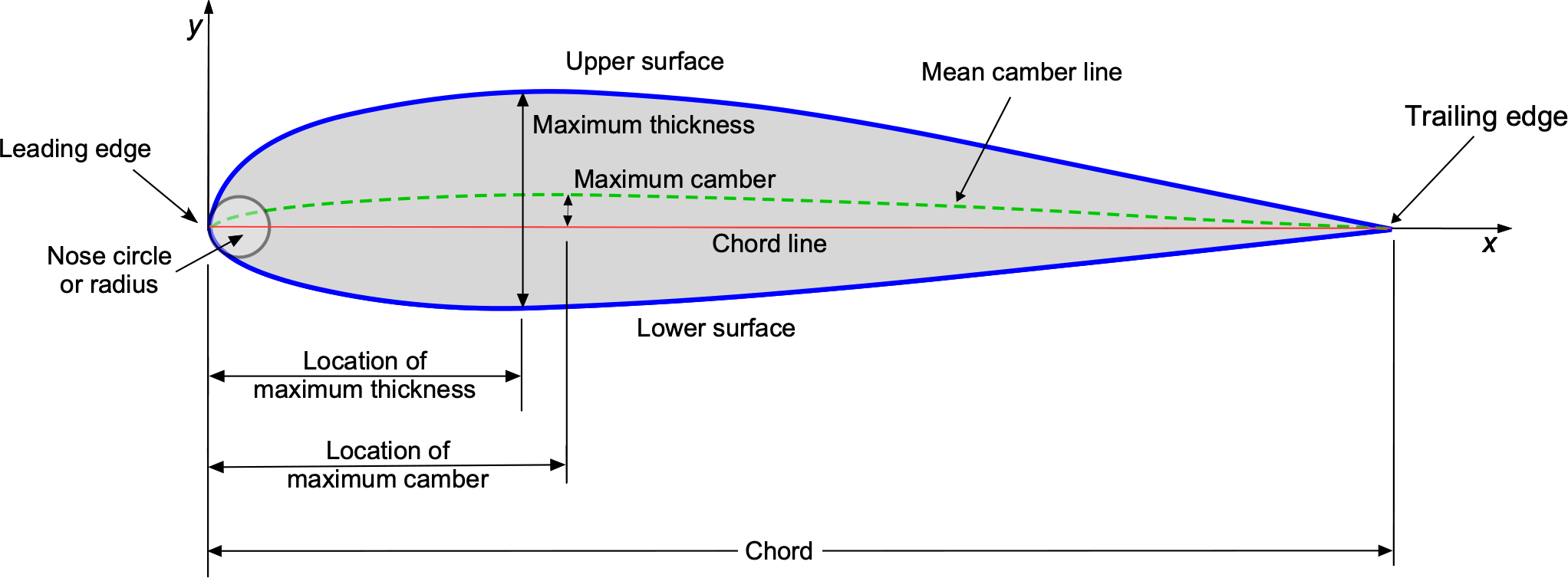

The basic geometry of an airfoil is described in terms of a profile shape or envelope that defines the curvature of its upper and lower surfaces. As shown in the figure below, airfoils can be either symmetric, meaning they have the same shape and curvature on both the upper and lower surfaces, or cambered, which means they have different shapes on the upper and lower surfaces. In addition, some airfoils have camber, where the trailing edge region has an upward or negative camber, known as reflex camber, which is often used on flying wings, helicopters, and autogiros.

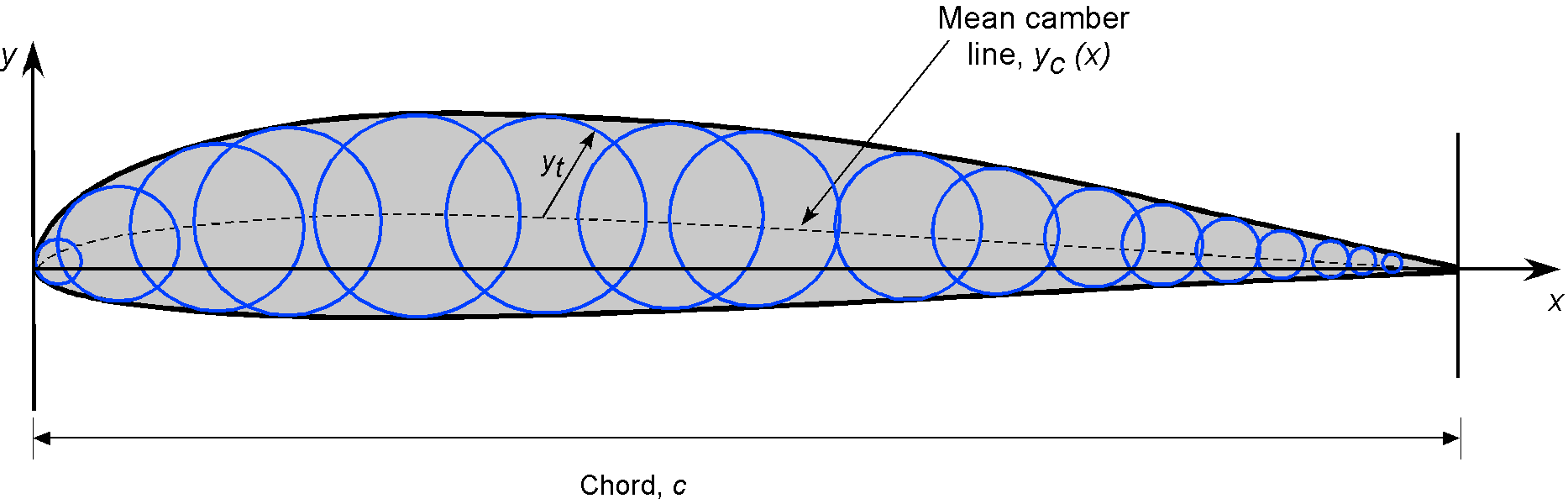

As shown in the following figure, the critical length dimension of an airfoil profile is defined in terms of its chordline; the chord is defined as the distance measured from the leading edge of the airfoil profile to its trailing edge. However, in the geometric construction of airfoil profiles, it is necessary to be more precise about how exactly the profile shape is defined, including the value and position of the maximum thickness (thickness-to-chord ratio), the value and position of the maximum camber, as well as the nose shape, such as its radius of curvature.

In most geometric constructions of airfoil profiles, the airfoil’s thickness envelope is defined so that the upper and lower camber surfaces evolve if the thickness is plotted perpendicular to the slope of a defined mean camberline. The mean camber of the airfoil profile measures its average curvature, and the shape and amount of the mean camber will also affect the shape and curvature of the airfoil’s upper and lower surfaces. There is a formalized geometric process for tracing the envelope in terms of the coordinates of the upper and lower profile shapes, which can also be tabulated for various purposes, such as plotting, creating a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) grid, or for use in computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM). In addition, the leading-edge shape of the airfoil is often defined geometrically by a nose radius, which also affects the airfoil’s aerodynamic characteristics.

Other geometric parameters of interest for airfoils include the maximum thickness and maximum camber, typically defined as ratios relative to the chord: the maximum thickness-to-chord ratio and the maximum camber ratio. The chordwise positions of these latter parameters can also be defined and used to describe the shape of the airfoil profile, particularly in relation to their effects on aerodynamic characteristics. For example, it is known that increasing the camber at the leading edge of an airfoil can increase its maximum lift coefficient to a certain point; however, camber will also increase pitching moments.

NACA Method of Drawing Airfoil Shapes

As early as 1920, research institutions in Europe and the U.S.A. began systematic measurement of the aerodynamic characteristics of airfoils already in practical use. This work organized the results into families of airfoils that produce specific aerodynamic characteristics. With a catalog of airfoils featuring measured aerodynamic characteristics, aircraft designers could quickly select the most suitable airfoil profile for their particular application.

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or the NACA, which is always pronounced as “N-A-C-A” and never “NACA,” conducted the most comprehensive and systematic study of the effect of airfoil shape on aerodynamic characteristics. Existing cambered airfoils, such as the Clark-Y and Gottingen sections, were known from the earliest wind tunnel experiments to have good aerodynamic characteristics. Therefore, the NACA used these airfoils as a basis; these airfoils had geometrically similar profiles when the camber was removed, and the airfoils were reduced to the same thickness-to-chord ratio. A polynomial curve fit defined the resulting thickness shape, which became fundamental to many subsequent NACA airfoil families, i.e., the classic NACA 00-series symmetric airfoils.

Geometric Construction

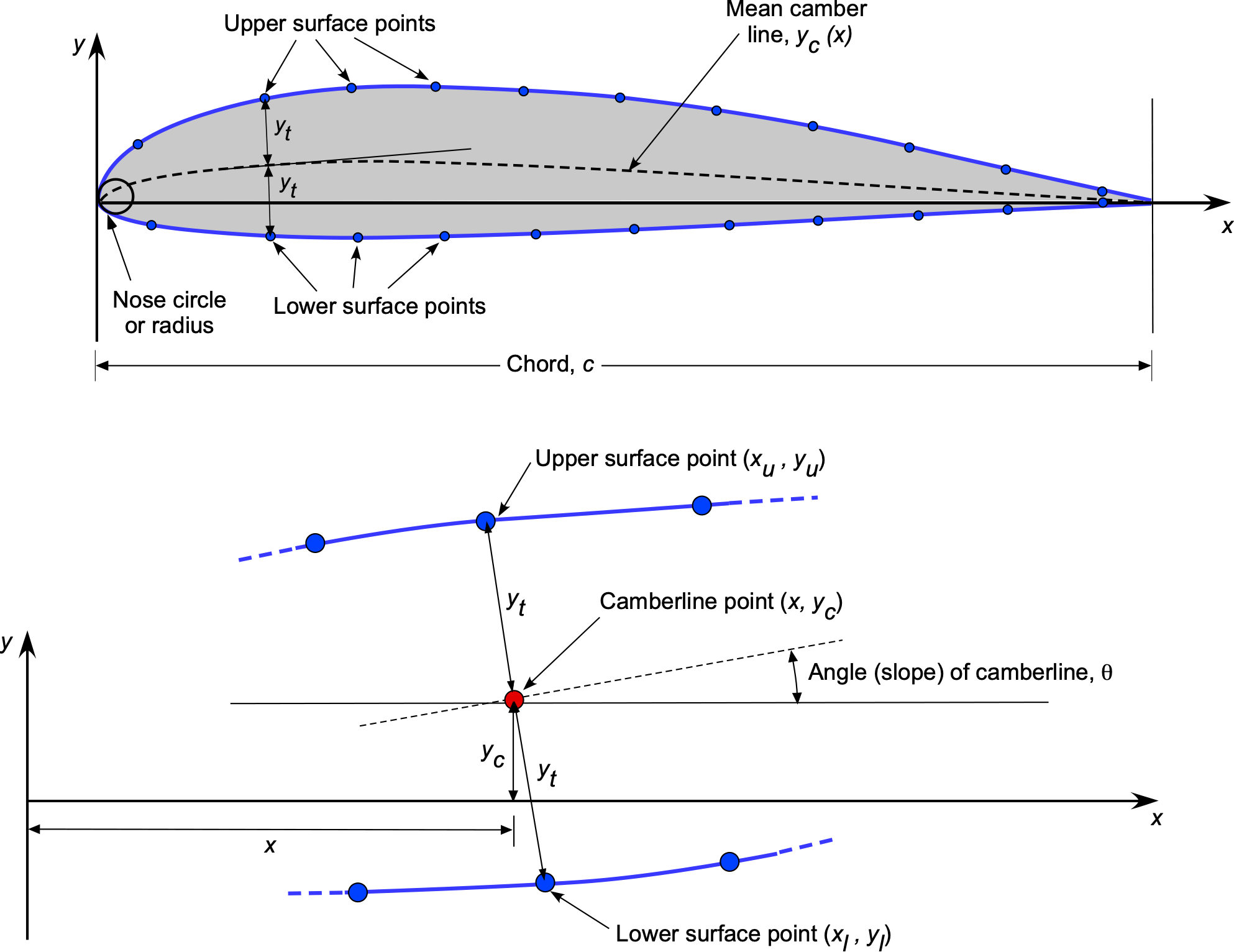

In the NACA method of defining the shape of an airfoil, a coordinate system is placed at the nose of the airfoil and is defined in terms of the and

distances, as shown in the figure below. The airfoil profile is then constructed of a series of upper and lower points by using a thickness shape

distributed around a camber line

by plotting the thickness perpendicular to the slope of the camberline, as detailed in the lower part of the figure.

(1)

The slope angle, , of the camberline is given by

(2)

where expresses the shape of the camberline. For airfoils with small camber, i.e., small values of surface slope angle

, applying the thickness along the

axis is a reasonable approximation; however, it is no longer necessary today because the process can be easily programmed on a computer.

It is usually preferred to plot airfoils using non-dimensional coordinates such that and

, i.e., coordinates non-dimensionalized with respect to the chord,

, so that

(3)

The slope angle, , of the camberline is given by

(4)

where expresses the shape of the camberline.

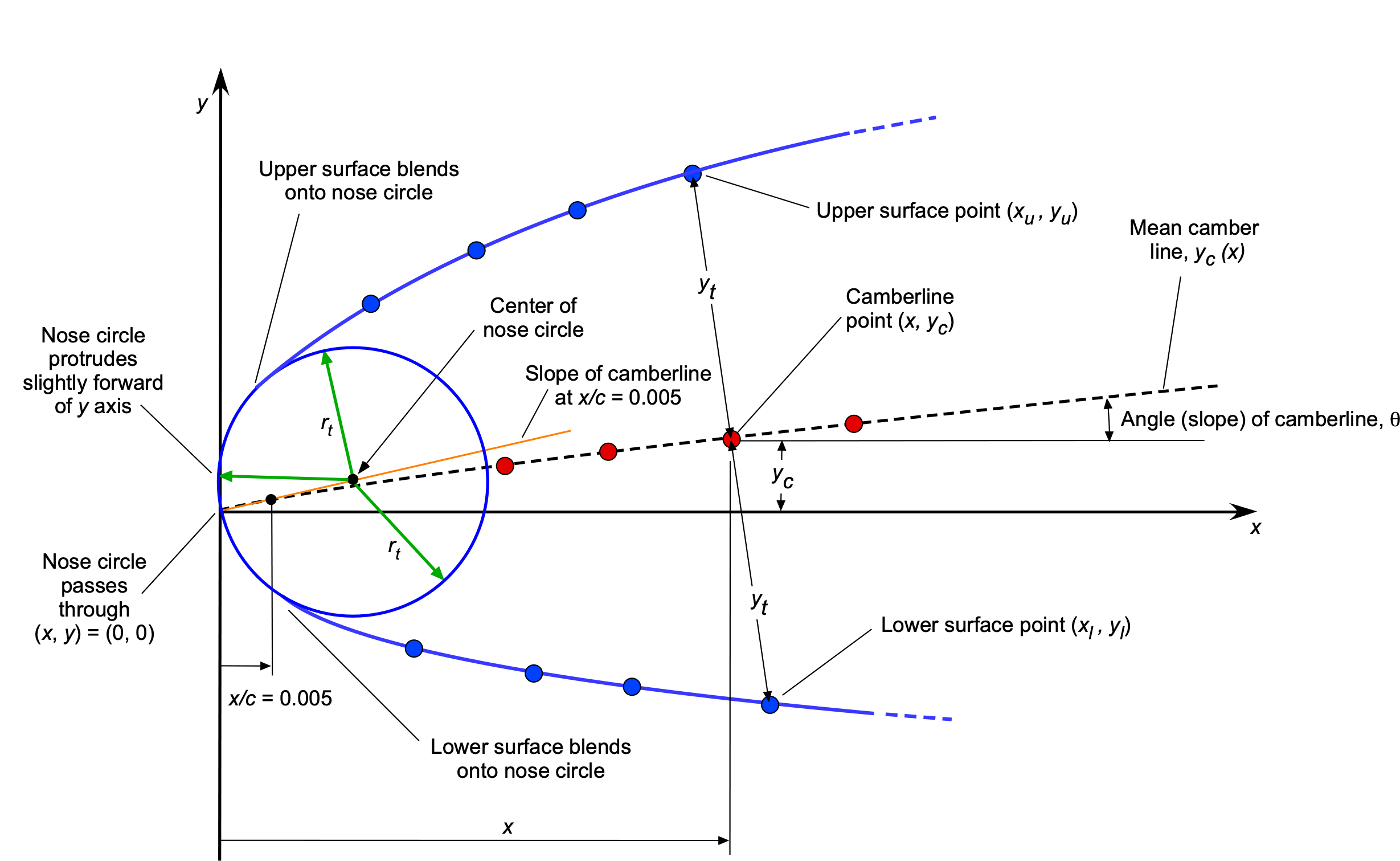

Nose Radius

The nose curvature or radius, , must also be formally located on the profile and is obtained with an inscribed circle. The center for the leading edge radius (defined by a circle) is found by drawing a straight line through the end of the chord at the origin of the axes, but with a slope equal to the slope of the camberline at

0.005, and then moving a distance along this line equal to the leading edge radius, as shown in the figure below. The resulting point then becomes the origin location for the leading-edge nose circle. Notice that the center of the nose circle will not lie on the mean camberline but at a point slightly above it.

An artifact of this construction method is that the leading edge of the airfoil protrudes very slightly beyond the -axis; however, this effect is of no practical significance, as it does not significantly affect the aerodynamic characteristics. For a symmetric airfoil, the center of the nose circle lies on the

-axis. In all cases, the nose circle is drawn and geometrically blended into the upper and lower surface coordinates; care should be taken when numerically implementing this process.

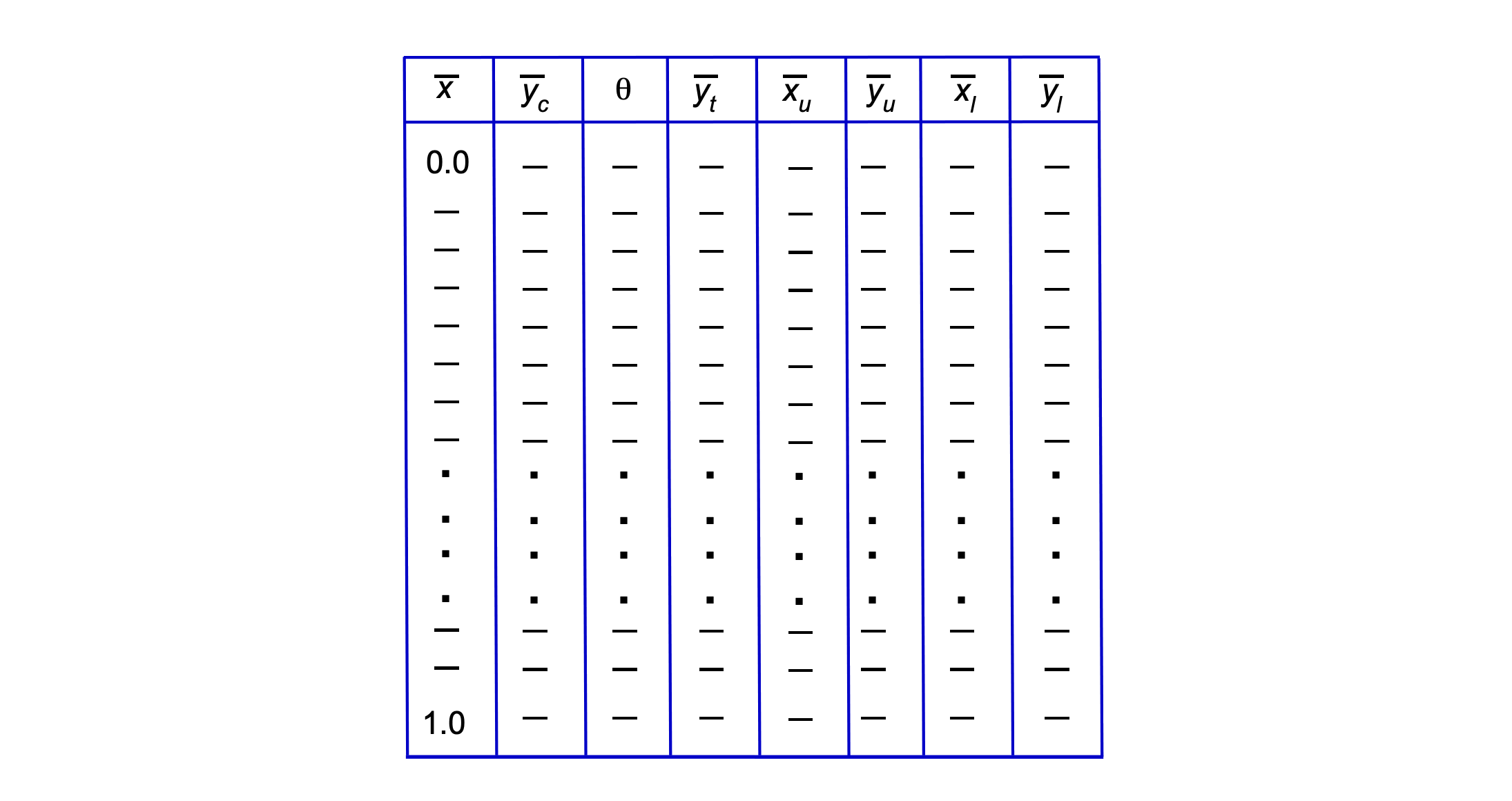

Airfoil Coordinates

The various upper and lower surface points can be exported to a data file, as shown in the figure below, and the airfoil’s final shape is then obtained by connecting the points. Generally, more points are needed in the nose region of the airfoil due to the section’s higher curvature. To give a reasonable approximation of the shape, 100 points should be used. For a CFD grid, CNC machine, or 3-D additive printing, the file may need to contain 500 to 1,000 points across the airfoil’s chord.

It will be noted that the NACA airfoils are designed to have a finite thickness at their trailing edges, due to manufacturing considerations. While a genuinely sharp trailing edge is theoretically ideal for facilitating smooth airflow and minimizing drag, it presents challenges in fabrication. By allowing a small, finite thickness at the trailing edge, the structural integrity and durability of the wing section can be ensured without significantly compromising its aerodynamic performance.

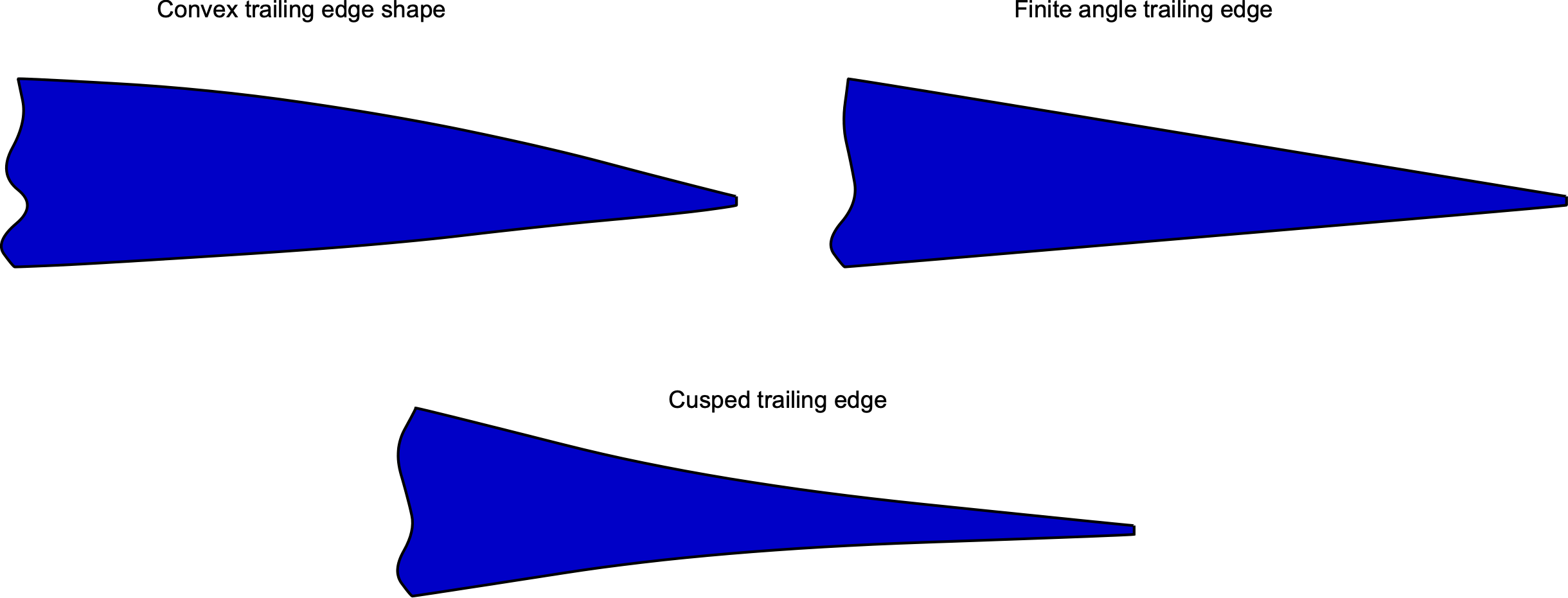

Trailing-Edge Shapes

Airfoil sections can have various trailing-edge shapes. The three general trailing edge shapes found in practice are convex, finite angle, and cusped, as shown in the figure below. As previously discussed, all these shapes will have a finite thickness at the trailing edge, meaning they are not infinitely thin but will have some thickness when implemented on an actual wing or airfoil.

Trailing-edge shapes include convex, finite-angle, and cusped. The convex trailing edge curves outward, away from the airfoil surface. This trailing edge has a sharp edge that forms an angle with the airfoil surface and terminates at a finite angle. Finite-angle trailing edges are commonly used in certain airfoil designs to achieve specific aerodynamic characteristics. A cusped trailing edge has a sharp, pointed shape. This trailing-edge type is less common and is typically used in specialized airfoil designs that require precise control over flow separation. The choice of trailing-edge shape depends on the specific requirements of the aerodynamic design, including maximum lift, minimum drag, and stall characteristics.

Circle Method of Airfoil Construction

Another way of drawing an airfoil section graphically is to compose it first as a series of circles of radius (or

if done non-dimensionally as a fraction of the chord) centered on the camberline, as shown in the figure below. The upper and lower surfaces of the airfoil are then formed from curves drawn tangential to all of the circles. While this method offers a simple graphical construction that can be helpful for visualizing the overall process of drawing an airfoil section, it is best to construct the surface shapes and tabulate the data points as previously described.

Connection to Aerodynamic Characteristics

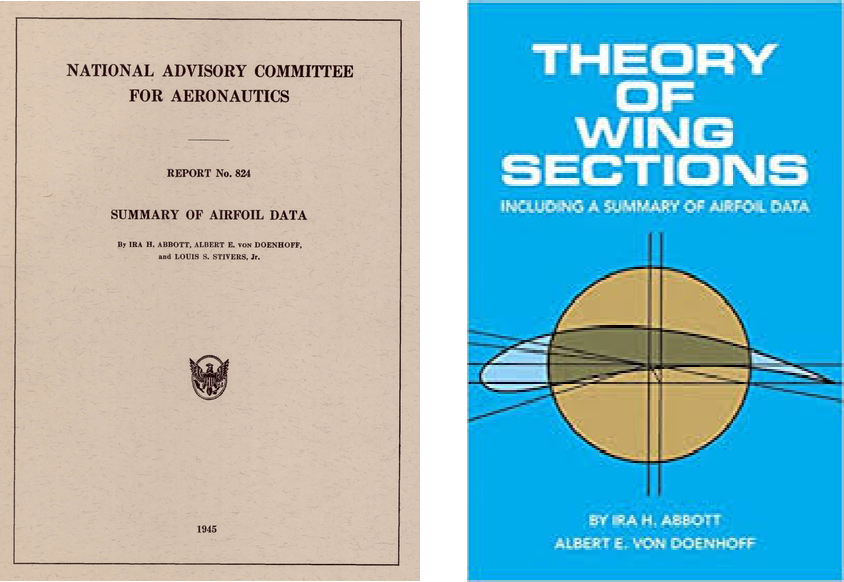

The foregoing NACA approach also allowed for the systematic construction of several families of airfoil sections differing only by a single geometric parameter, such as camber, the location of the maximum camber, the maximum thickness-to-chord ratio, and its location. The primary geometric characteristics that affect the airfoil characteristics include the maximum camber, its distance aft of the leading edge, and the leading-edge nose curvature (nose radius). The various families of airfoils developed by NACA were then tested in the wind tunnel to measure the effects of varying the critical geometrical parameters on the lift, drag, and pitching moment characteristics as a function of angle of attack, as well as, in some cases, the chord Reynolds number and Mach number.

This was a monumental undertaking by the engineers at NACA, and even today, it remains one of the most definitive catalogs of aerodynamic measurements on low-speed airfoil sections. A summary of the results is documented in considerable detail in the NACA report, later published in the second half of the book “Theory of Wing Sections, Including a Summary of Airfoil Data” by Ira H. Abbott and A. E. von Doenhoff.

Symmetrical NACA Airfoils

Symmetrical airfoil sections are often chosen for the horizontal and vertical tail surfaces of airplanes and other aircraft. The upper () and lower (

) surfaces of the NACA 00-series (sometimes designated as 00-XX) or four-digit symmetrical sections are described by the polynomial

(5)

where ,

, and

, i.e., the geometry of the airfoil and the coordinates are expressed as a fraction of its chord or for

. The coefficients

through

were obtained by a curve fit to the best-known airfoil shapes when they were all reduced to the same thickness-to-chord ratio. They are given by:

= 0.2969 ,

= 0.1260,

= 0.3516,

= 0.2843 and

= 0.1015. The factor of

is used to scale the coordinates to the correct thickness-to-chord ratio.

The shape of the airfoil is then obtained by plotting as a function of

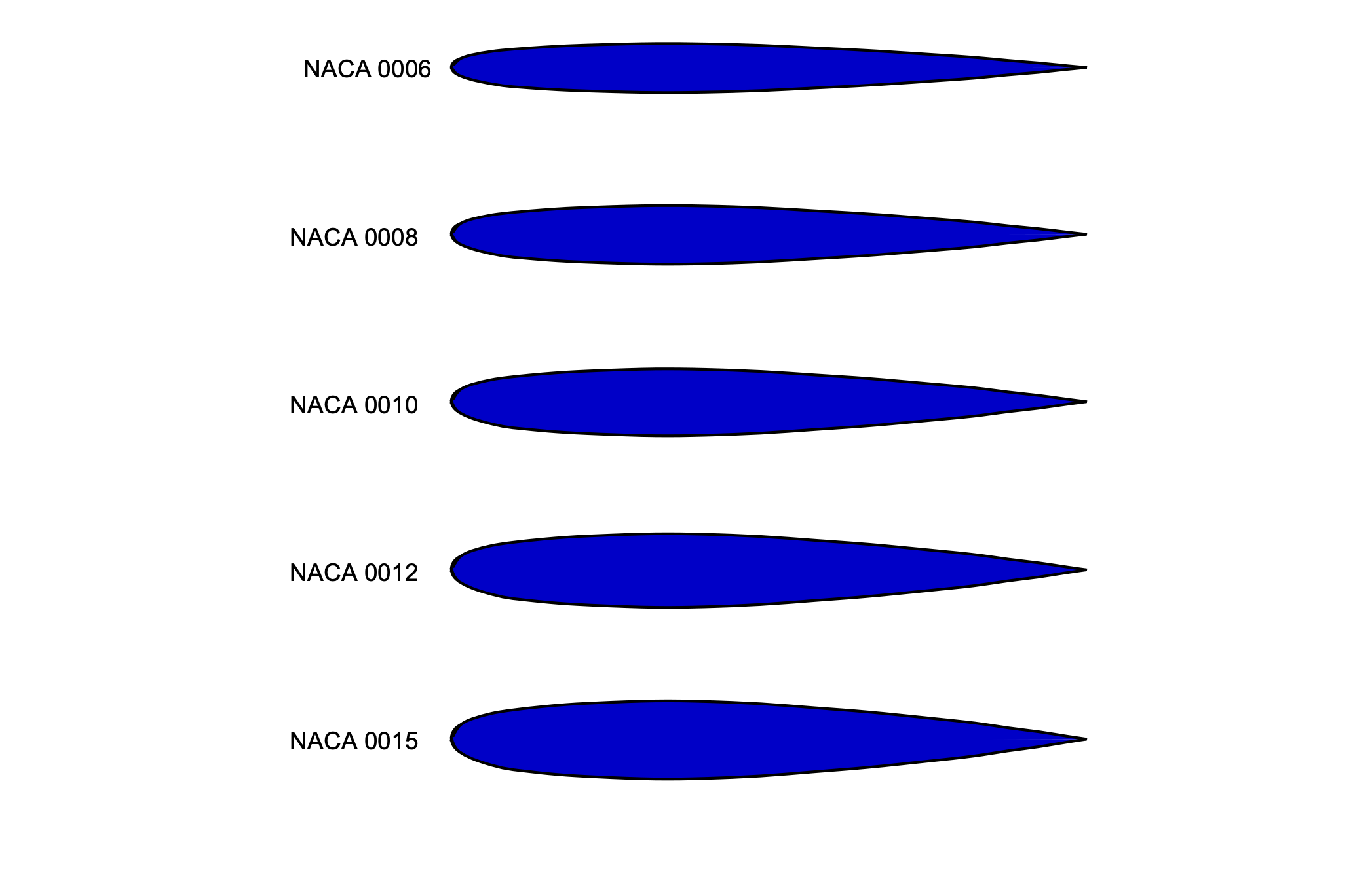

and for any number of points; at least 50 points and, more typically, 100 points will be required to define the airfoil shape to good fidelity. The corresponding leading-edge nose radius of the airfoil is given by

(6)

which is smoothly blended into the upper and lower surfaces to give a circular arc shape at the leading edge, as previously described. The nose radius must be included; otherwise, the airfoil shape is incomplete, and the leading edge will become pointed. Examples of the NACA 00-series symmetric airfoils are shown in the figure below. The number denotes the thickness-to-chord ratio in percent of the chord; e.g., a NACA 0015 has a 15% thickness-to-chord ratio, which means .

Cambered NACA Airfoils

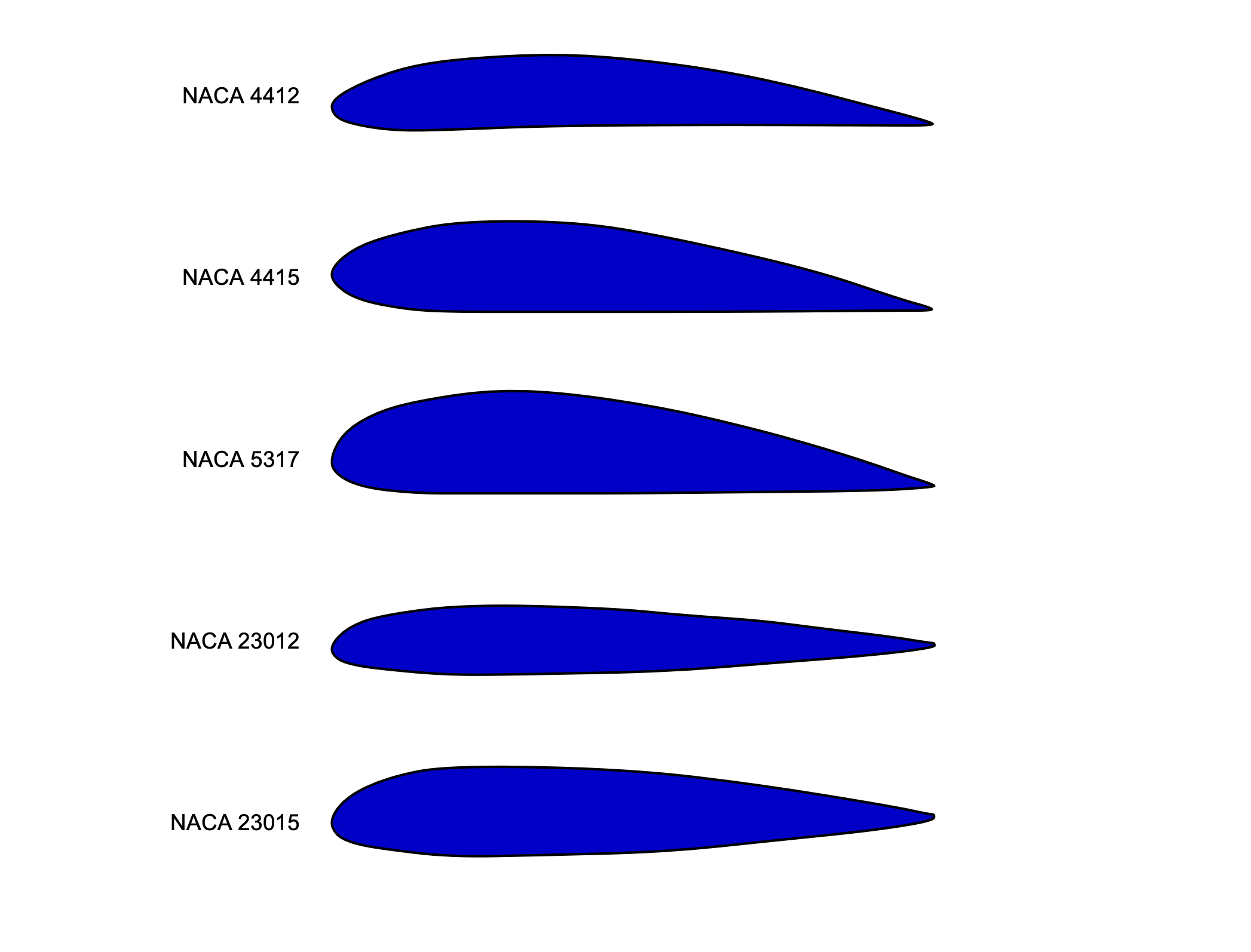

As previously discussed, cambered airfoils are constructed by distributing the thickness envelope (as defined above) around a mean camberline shape. The camberline shape is specified as a function of

, i.e.,

. Precisely, the thickness envelope is plotted perpendicular to the camberline to trace out the profiles of the upper and lower surfaces. There are many camber line profiles in the NACA portfolio, including the two- and three-digit camber lines, as shown in the figure below. The first two digits define the amount of camber and the chordwise location of maximum camber. For example, the NACA 2408 has a 2% camber, the maximum camber location is at 40% of the chord length, and the airfoil is 8% thick.

NACA Two-Digit Camberlines

The simplest cambered airfoils are used to form the NACA 4-digit series, which comprises the standard NACA four-digit thickness envelopes and the following camberline based on two coefficients, i.e.,

(7)

where is the maximum camber (100

is the first of the four digits),

is the location of the maximum camber, with 10

being the second digit in the NACA 4-digit airfoil description. Notice that the camberline is in two parts: one for the front of the airfoil and the other for the rear. The slopes of the camberline are

(8)

NACA Three-Digit Camberlines

The NACA three-digit mean (camber) lines are also very popular and are given in this case in terms of two equations and three coefficients, i.e.,

(9)

where the coefficients of the camberline are given in the table below. Notice, again, that the camber line is expressed in two parts.

| Mean Line | |||

| 210 | 0.05 | 0.0580 | 361.4 |

| 220 | 0.10 | 0.1260 | 51.64 |

| 230 | 0.15 | 0.2025 | 15.957 |

| 240 | 0.20 | 0.2900 | 6.643 |

| 250 | 0.25 | 0.3910 | 2.230 |

The forward and aft slopes of the camberline are

(10)

Other NACA Airfoils

Modifications to the NACA four-digit and five-digit series of airfoil sections include the addition of reflex camber to produce a zero pitching moment, as well as changes in the nose radius and position of thickness to enhance maximum lift capability. These modifications aimed to enhance the versatility and performance of specific airfoil classes for a broader range of applications, including low-speed aircraft, tailless designs, high-lift configurations, and helicopter rotors.

Modified 4-Digit Airfoil

These airfoils are an extension of the standard 4-digit 00-series, designed to allow variations in the leading-edge radius and the location of maximum thickness. The numbering system is expressed as NACA 00XX-IT, where 00XX denotes the standard 4-digit symmetric airfoil designation, and the IT suffix indicates a modification to the thickness distribution. The suffix parameters are defined as: is the designation of the value of the leading-edge radius;

is the chordwise position of the maximum thickness in tenths of the chord.

The leading-edge radius for these airfoils is given by

(11)

or by

(12)

If = 6, this value corresponds to the leading-edge radius of the standard 4-digit symmetric 00XX airfoils.

For example, the designation NACA 0012-74 refers to a symmetrical airfoil with a maximum thickness-to-chord ratio, but the maximum thickness is now located at

and a leading-edge radius of

, which is larger than the standard value for the 4-digit airfoils.

NACA 3-Digit 231-Series Reflexed Airfoils

The camberline for the NACA 3-digit 231-series reflexed airfoils is of some interest because they are designed to give zero-pitching moments about the 1/4-chord axis. In this regard, they are considered suitable for rotor blades (e.g., those of a helicopter or an autogiro) because they need to minimize torsional twisting moments on the blades. The camberline of these airfoils is defined by two equations, i.e.,

(13)

where ,

,

, and

.

The slopes of the camberline are

(14)

NACA Six-Digit Series

Another set of NACA airfoils that have seen some use on various aircraft is the six-digit series. These airfoils were designed to achieve lower drag, higher drag divergence Mach numbers, and higher maximum lift coefficients. Their profiles are conducive to maintaining an extensive run of laminar flow over the leading-edge region, thereby lowering skin friction drag, at least over a range of angles of attack limited to low lift coefficients.

This latter goal is achieved using camberlines that produce a more uniform pressure loading from the leading edge to a distance . After that, the loading decreases linearly to zero at the trailing edge. The favorable pressure gradients tend to give the airfoils lower drag than other airfoils, at least over a limited range of attack angles. Unfortunately, surface contaminants or other disturbances that cause transition quickly spoil the characteristics of laminar-flow airfoils, sometimes resulting in significant adverse effects.

Many designator combinations are used in the NACA six-digit airfoil number system, which can become quite complicated. For example, consider the NACA 64-215

section. In this case, the number 6 denotes the airfoil series, and the number 4 represents the position of minimum pressure in tenths of the chord for the basic symmetric section. The number 3 denotes the range of lift coefficient in tenths above and below the design lift coefficient for which low drag may be obtained. The number 2 after the dash indicates a design lift coefficient of 0.2, and the number 15 denotes a 15% thickness-to-chord ratio.

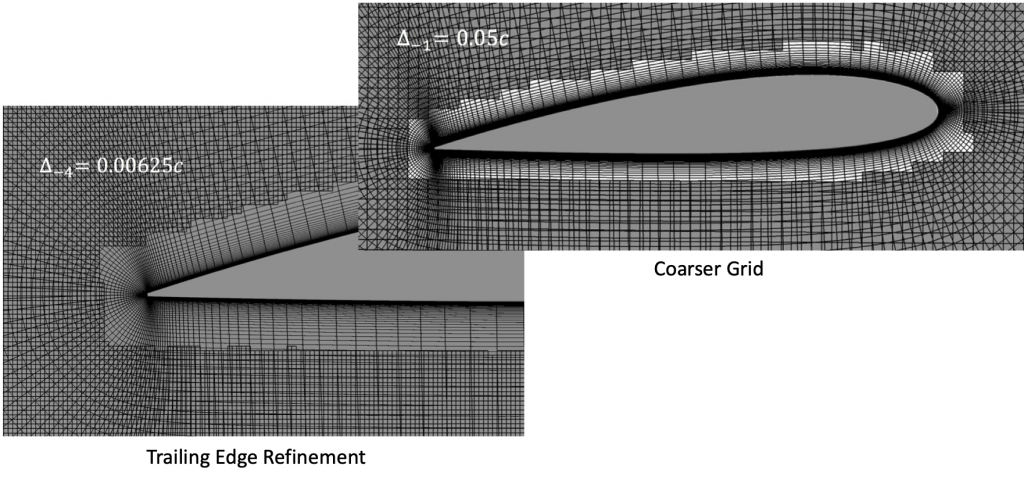

Grid Generation for CFD

The numerical generation of airfoil coordinates can also produce input points, grids, or meshes for calculating their aerodynamic characteristics using programs like XFOIL or other methods, such as computational fluid dynamics. CFD grids are composed of discrete cells over which the conservation laws of fluid mechanics can be applied. An example of a grid about an airfoil section is shown in the figure below. Refinement of the grid is needed near the airfoil surface to resolve the thin boundary layers. Grid refinement may also be required at the trailing edge to model the merging of the upper and lower surface boundary layers and the development of the downstream wake.

The resulting flow solution can then be used to calculate various properties around the airfoil, including local pressure and local Mach number. CFD methods can also be used to design the shape of an airfoil to obtain a specified level of performance. However, this tends to be lengthy because of its iterative nature and slow numerical convergence. Nevertheless, the ability to design airfoil shapes on a computer, to a certain extent, is much quicker than testing numerous prospective shapes in a wind tunnel.

The grid generation process for CFD solutions can take various forms, including both structured and unstructured. Structured grids are geometrically regular, whereas unstructured grids have more randomly distributed points, a valuable approach that can reduce the computational time required to find a flow solution. Several software tools are available to engineers to help create grids for particular airfoil shapes. The fidelity of the resulting aerodynamic solution strongly depends on the grid, especially the number of grid points, which can reach many millions. Of course, the numerical cost (and time) to obtain a solution increases commensurately with the number of grid points.

Other Types of Airfoils

Various airfoil types are used, each tailored to meet specific design goals and performance criteria for a particular flight vehicle. These include supersonic, propeller, and low-Reynolds-number airfoils, each distinguished by unique geometric features. The specialized design of these airfoils enables aircraft and other aerodynamic vehicles to achieve their best performance in alignment with their intended functions and operational demands.

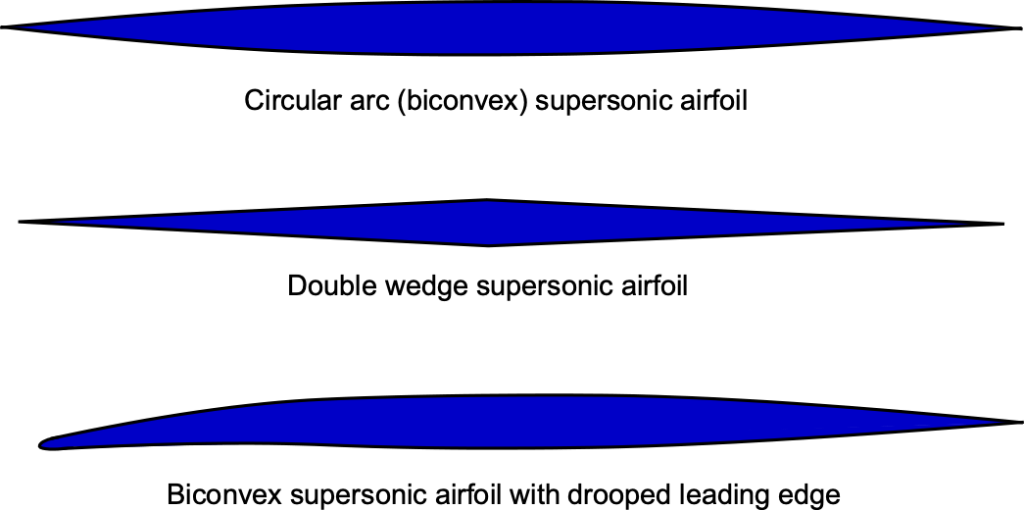

Supersonic Airfoils

The well-rounded, cambered airfoil sections, which are well-suited to subsonic flight speed, are generally inappropriate for high-speed and supersonic flight. Supersonic airfoils are distinguished by their geometric shapes, which are characterized by being thin (i.e., having a low thickness-to-chord ratio) and featuring sharp leading edges. Supersonic airfoils generally have thinner sections formed of either angled planes called double-wedge airfoils or opposed circular arcs called biconvex airfoils, as shown below. The sharp leading edges on supersonic airfoils prevent the formation of a detached bow shock in front of the airfoil, which is a significant source of drag called wave drag.

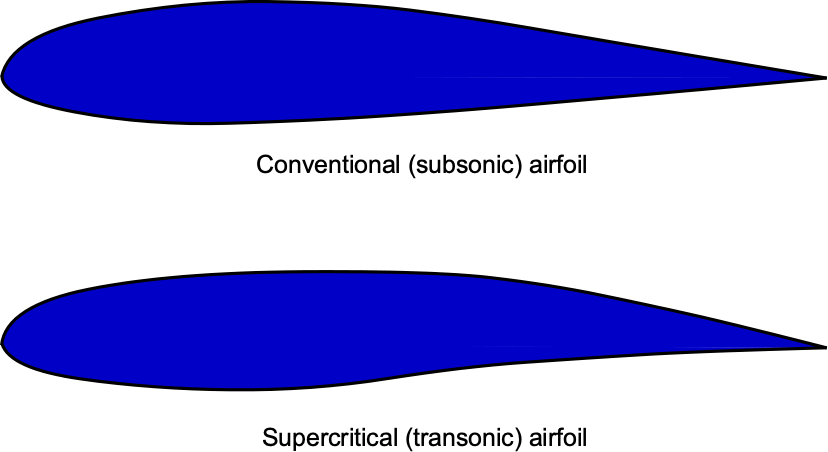

Supercritical Airfoils

Because commercial airliners have been designed to reach higher and higher cruise speeds approaching the speed of sound, i.e., for flight at transonic Mach numbers over 0.8, this requirement has led to the design of a unique wing shape called a supercritical wing. A supercritical wing also uses a supercritical airfoil to reduce the strength of shock waves, thereby reducing wave drag. This principle is used in transonic wing and airfoil design to control the expansion of the flow to supersonic speed and its subsequent recompression. The upshot is a delay in the onset of supercritical flow on the airfoil’s upper surface (i.e., when the flow first becomes supersonic), which reduces wave drag for a given freestream Mach number or increases the Mach number before the drag rise occurs.

The figure below shows that the classic supercritical airfoil shape is distinctive. It has a point of maximum thickness fairly aft on the chord, with a relatively flat upper surface with a slight camber. However, such airfoils also tend to have significant camber at their trailing edges, compensating for the lift reduction from the front part of the airfoil section. Supercritical airfoils were extensively studied and refined during the 1960s by Richard Whitcomb and the NACA. Today, all commercial jet airliners utilize a form of supercritical airfoil, which enables them to cruise with high efficiency at flight Mach numbers exceeding 0.8.

Laminar Flow Airfoils

Sailplanes and other specific aircraft utilize laminar flow airfoils, designed to maximize the extent of the laminar boundary layer over the airfoil’s leading edge, thereby substantially reducing skin friction drag. Franz Xavier “FX” Wortmann designed a series of airfoils, known as the FX-airfoils, specifically for sailplane applications, examples of which are shown in the figure below.

The geometric shapes of these airfoils differ from those used on most airplanes and are designed to have a point of maximum thickness close to the mid-chord. This shape produces a favorable pressure gradient over the leading edge, helping the boundary layer remain smooth and laminar farther downstream. Laminar flow produces lower skin friction and drag on the airfoil. The downside is that such airfoils typically produce lower maximum lift coefficients, i.e., a stall occurs at lower angles of attack. Such airfoils are also very sensitive to the surface finish, which must be glassy-smooth and free of contamination (e.g., bugs and fingerprints) to realize the low “laminar” drag values.

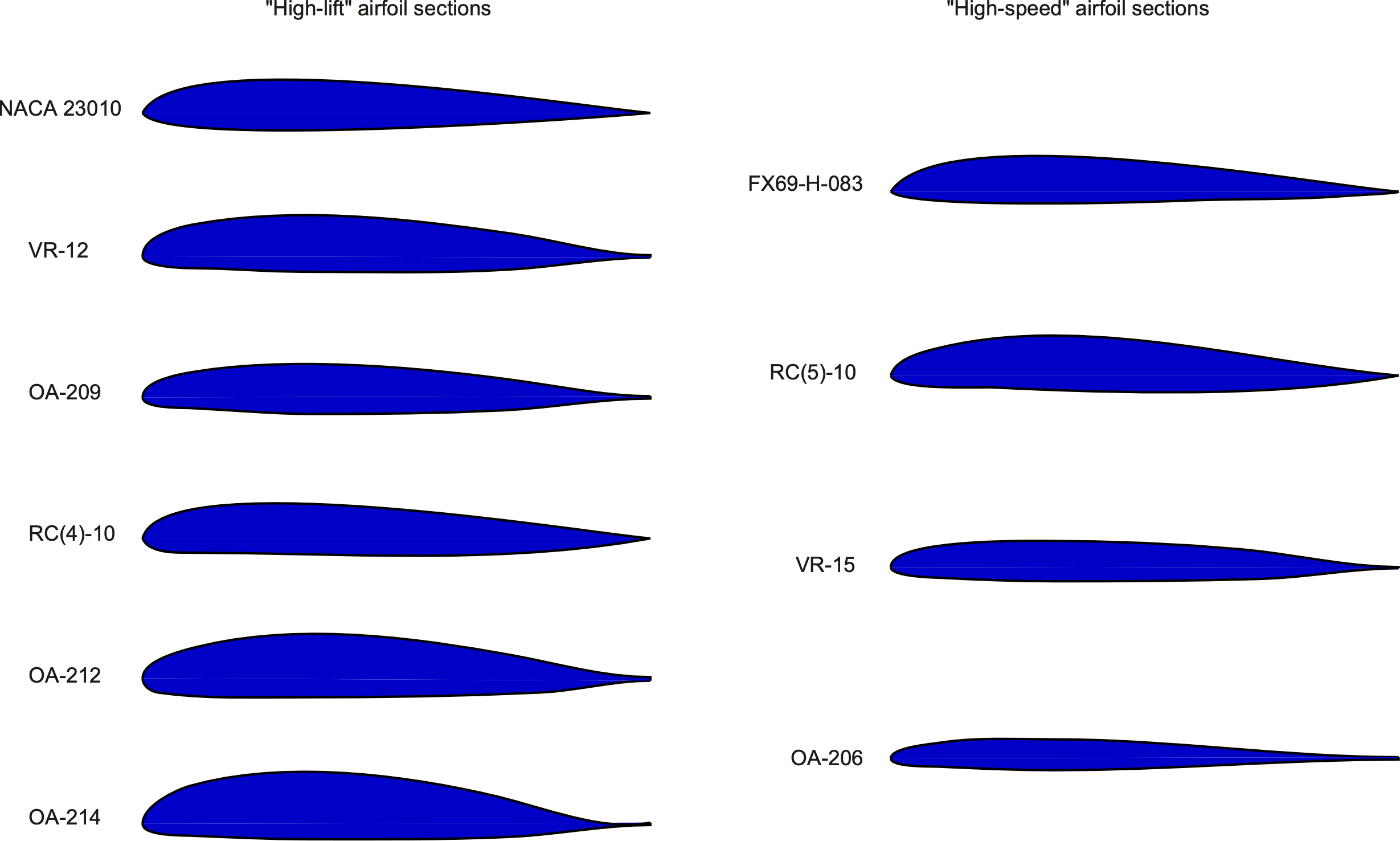

Rotorcraft Airfoils

Rotorcraft airfoil sections are specifically designed to enhance the aerodynamic performance of rotor blades in helicopters, autogiros, and other types of rotorcraft. These airfoil sections address the unique aerodynamic challenges of rotorcraft, including operation at high angles of attack near stall, transonic flow, the need for both high lift and low drag, and low pitching moments.

Several specific airfoil designs have been tailored for different performance aspects, as shown in the figure below. Each is well known for its high performance in rotorcraft applications. These airfoils are designed to improve hovering capabilities by generating high lift coefficients. Additionally, they are optimized to maximize their lift-to-drag ratios, improving the overall efficiency and speed of the rotorcraft, particularly during forward flight. The need for low-pitching moments on blades means that some airfoils are distinctly reflexed. Some airfoils in the series are also optimized for transonic flow conditions, which can occur at rotor blade tips.

Extensive wind tunnel testing and modern computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations have validated the aerodynamic performance of these airfoil sections, providing detailed insights into their behavior under various flight conditions. Developing these rotorcraft airfoil sections has positively impacted the design and performance of modern helicopters and other rotorcraft, enabling them to carry a greater payload and fly faster.

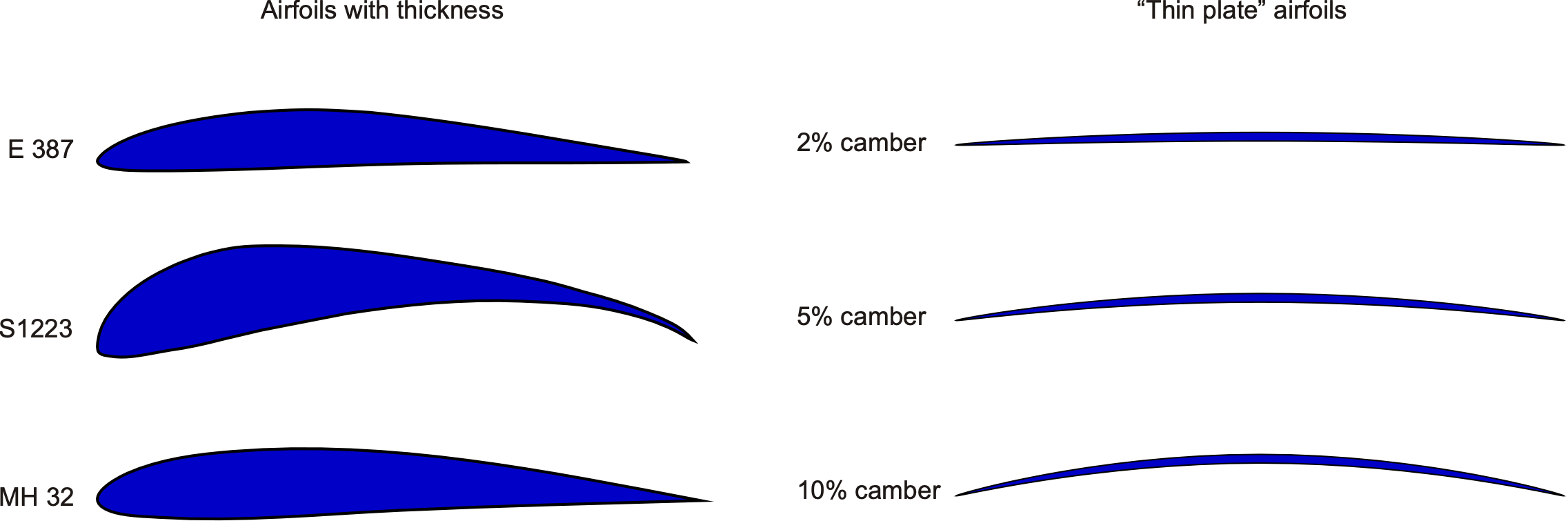

Low Reynolds Number Airfoils

So-called “low Reynolds number airfoils” are designed to perform efficiently at low chord Reynolds numbers, typically encountered in small-scale aircraft such as drones and UAVs. In this context, low Reynolds numbers are defined as those below 10 based on the airfoil chord and perhaps as low as 10

in some applications. Under these conditions, the boundary layer flows over the airfoil tends to remain laminar for a longer downstream distance along the chord. Still, the boundary layers are thicker compared to operations at higher chord Reynolds numbers. The formation of a long separation bubble on the top (suction) surface is a characteristic of such low-Reynolds-number flows, followed by a transition to turbulence. However, laminar flow separation and abrupt stall can also occur if the airfoil shape is improperly designed for low Reynolds number applications.

Low Reynolds number airfoils are specifically designed to achieve higher lift-to-drag ratios than those obtained with more conventional airfoil shapes when operated at these low Reynolds numbers. Some design considerations for low-Reynolds-number airfoil sections include a well-rounded leading edge and a prolonged favorable pressure gradient along the leading edge to encourage a long run of laminar flow. These airfoils are typically designed with camber and thickness distributions that maintain laminar flow to at least mid-chord. Their corresponding shapes produce relatively mild adverse pressure gradients over the aft part of the airfoil, thereby preventing premature stall.

The figure below shows examples of airfoils designed for low-Reynolds-number applications. These include the Eppler E387, known for its good performance at low Reynolds numbers and often used in model aircraft; the S1223, designed to maximize lift and minimize drag for small UAVs; and the more conventionally styled MH 32, used in various small-scale applications. A distinctive feature of these airfoils is a point of maximum thickness relatively far aft of the leading edge. This produces a favorable pressure gradient over the leading-edge region and helps the boundary layer remain laminar for as long as possible.

In some respects, conventional aerodynamic wisdom does not apply to the design of low-Reynolds-number airfoils. Indeed, wind tunnel tests and CFD calculations with thin plates have surprisingly shown that such airfoil shapes can outperform conventional airfoils with thickness in terms of lift production and aerodynamic efficiency at low Reynolds numbers, especially if they use some camber. Thin, plate-like airfoils have also been shown to be less sensitive aerodynamically to changes in chord Reynolds number (below 10) compared to conventional airfoils, making them more robust in applications with variable flow conditions, such as along the blade span of small-scale rotors and propellers.

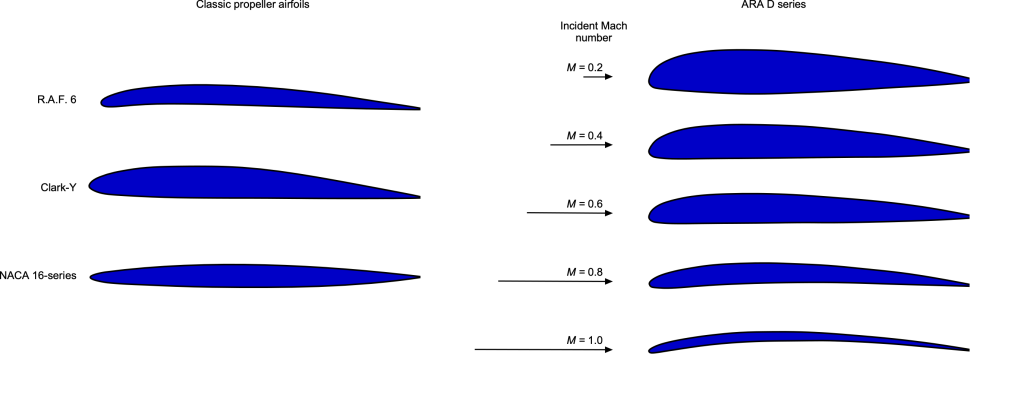

Propeller Airfoils

Propeller airfoils are the cross-sectional shapes of the propeller blades, designed to efficiently convert rotational motion into thrust. Airfoils for propeller applications have traditionally been “flat-bottom” Clark Y series with a lower surface, constrained, in part, by the manufacturing limitations of metal propellers. Propellers have also used the R.A.F. 6 airfoil, with the thickness being reduced at the blade tip. The classic choice at the tips of many propeller blades is the NACA 16 “transonic” series, characterized by maximum thickness at approximately 50% chord and a relatively sharp leading edge (i.e., a small leading-edge radius).

Many contemporary propellers use the Clark Y profile for the inner 50% of the blade, transitioning to the NACA 16 series (perhaps with some camber) in the outer part to take advantage of its higher drag-divergence Mach number. The extreme blade tips of propellers are usually as thin as structurally possible. The aerodynamic principle is to delay the onset of supersonic flow when the propeller operates at high airspeeds and high helical Mach numbers, thereby minimizing subsequent thrust and efficiency losses.

Modern propellers utilize sophisticated blade shapes that optimize the blade section angle of attack to maximize thrust and minimize drag. In the 1970s, the ARA D series of propeller airfoil sections[3]These airfoils were developed to address and alleviate previous manufacturing constraints associated with the transition to composite propeller blade manufacturing.[4] The Aircraft Research Association ARA D series airfoils, which are shown in the figure below, featured increased camber on the underside, a drooped leading edge to prevent stall at high angles of attack, and a more rounded leading edge radius. Thicker airfoils are required at the blade root to withstand the structural loads resulting from bending, torsion, and centrifugal forces. The maximum camber is positioned well forward at 10% for low-sectional Mach number applications, moving back to 30% at higher Mach numbers to delay shock wave formation and drag rise. As shown in the figure, the ARA D section for is very thin, with a thickness-to-chord ratio of 3%, and significantly cambered, at only 5%. In each case, the trailing edge is designed to be “blunt” for manufacturing reasons. Most propeller manufacturers have followed the same direction as the ARA D series, but these are primarily proprietary airfoils with limited dissemination.

These improvements to the airfoil sections along the blade span of a propeller aim to increase thrust and efficiency, especially in applications with high helical Mach numbers, by delaying shock formation and drag rise at the blade tips. The ARA D and similar advanced propeller airfoils significantly outperform legacy designs by optimizing camber and thickness distributions along the blade span, enhancing sectional lift-to-drag ratios, and preventing stall at higher thrust. The upshot of these enhancements is higher propulsive efficiency, which is crucial for modern high-speed propeller-driven aircraft, while also contributing to reduced noise (lower shock wave strength) and improved fuel efficiency.

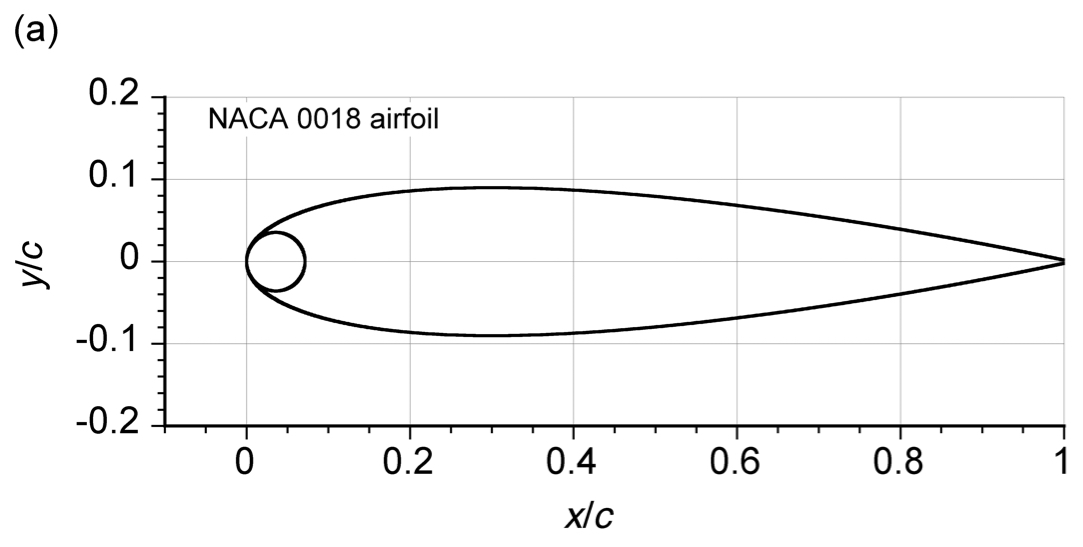

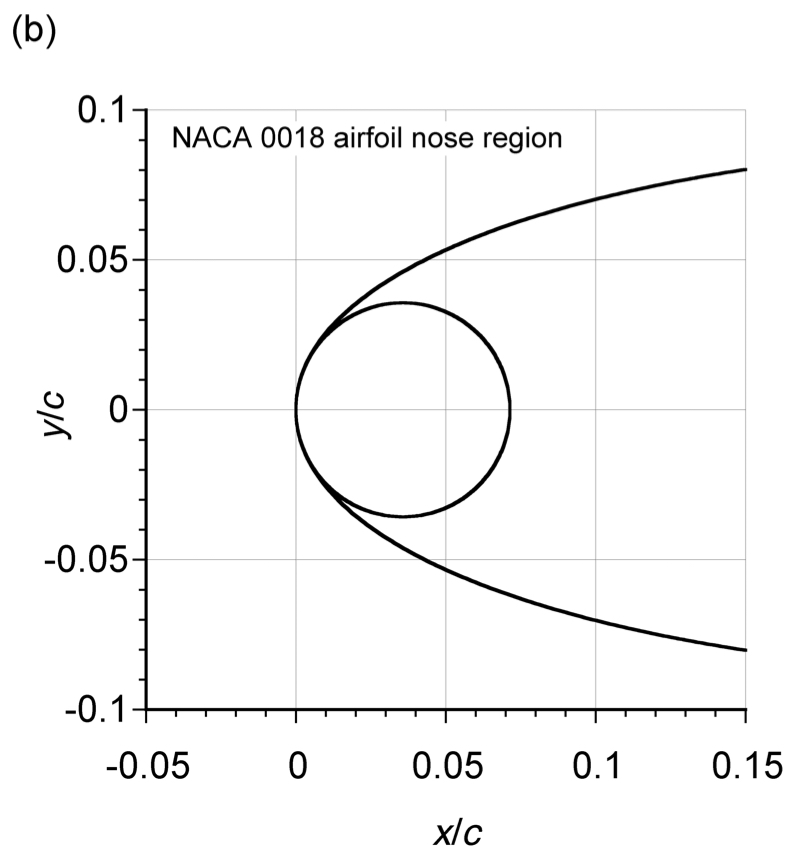

Examples to Try

There are many airfoils to choose from, but for the student, understanding the NACA method of geometric airfoil construction is valuable. It is a systematic and mathematically straightforward approach, and the algorithm lends itself naturally to computer programming. For example, the shape of a NACA 0018 airfoil takes no more than plotting the shape of the upper and lower surfaces using

(15)

where, in this case, . The corresponding leading-edge radius of the airfoil is

.

The shape of the airfoil is obtained by plotting as a function of

; the results can be tabulated for any number of specified discrete points along the chord line, but 50 to 100 is usually enough for a good definition, as shown in the two figures below. For practical reasons, all NACA airfoils have a finite thickness at their trailing edges, so the values of

at

are non-zero. Recall that the nose curvature or radius,

, must also be formally located on the profile and is obtained with an inscribed circle. The center of the leading edge radius for a symmetric airfoil lies on the

axis.

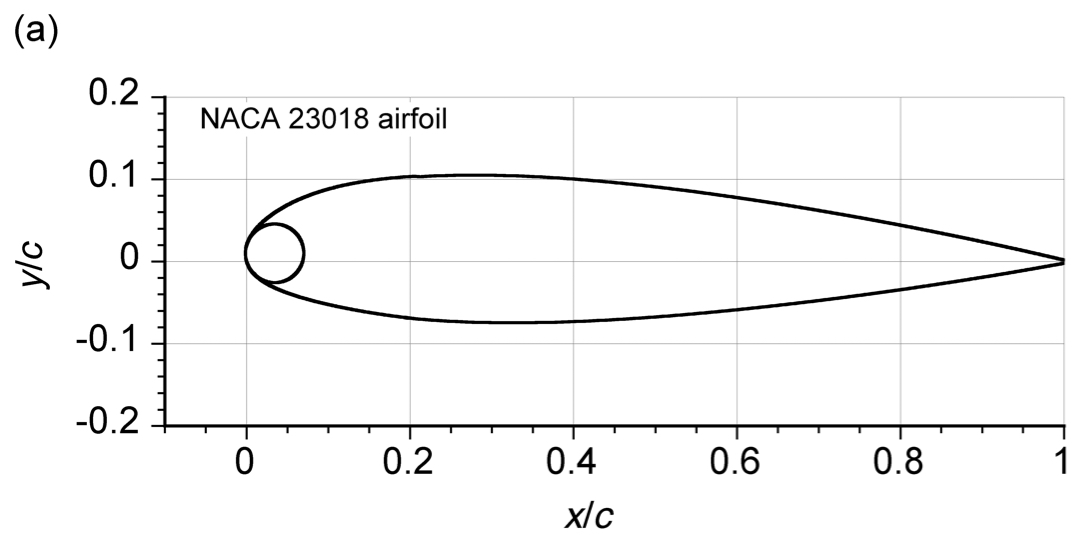

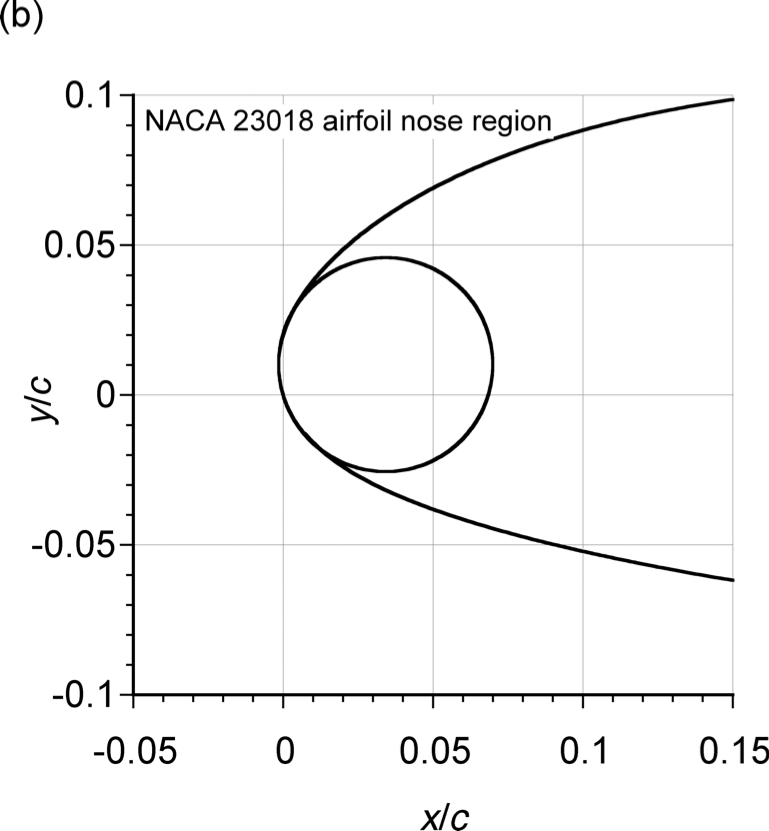

The NACA 23018 airfoil section is a cambered airfoil comprised of the NACA 0018 thickness envelope (described above) wrapped around the NACA 230 mean camberline, as given by

(16)

where ,

and

for the 230 camberline. The slope of the camber line is

(17)

and the slope angle of the camberline is . The coordinates are then

(18)

The resulting NACA 23018 airfoil is shown in the two figures below. Again, it is essential to properly locate the nose radius. In the case of a cambered airfoil, the center of the leading edge radius is found by drawing a straight line through the end of the chord at the origin of the axes, but with a slope equal to the slope of the camberline at and then moving a distance along this line equal to the leading edge radius. It is apparent on the enlarged plot of the nose region that the leading-edge part of the nose radius protrudes very slightly forward of the

axis (small negative values of

); this is an artifact of the construction technique and is of no practical significance when building a wing with such an airfoil.

MATLAB code to draw a cambered NACA 230-series airfoil. Other NACA camberlines can also be examined more thoroughly to understand the drawing process for NACA airfoil shapes.

Click here to show/hide the MATLAB code.

clc

clear

close all

t = 0.12;

m = 0.2025; %location of maximum camber

k1 = 15.957; %constant

r = 1.1019.*(t^2); %radius of leading edge circle

x1 = linspace(r/3,m,round(m.*500)); %x coordinates nose circle to m

x2 = linspace(m,1,round((1-m).*500)); %x coordinates m to 1

y_cam_1 = (1./6).*k1.*((x1.^3)-(3.*m.*(x1.^2))+((m.^2).*(3-m).*x1)); %camber line y coord 0 to m

y_cam_2 = (1./6).*k1.*(m.^3).*(1-x2); %camber line y coord m to 1

x = [x1 x2]; %merged x coordinates

y_cam = [y_cam_1 y_cam_2]; %merged y camber coordinates

dy_cam_1 = (1./6).*k1.*((3.*(x1.^2))-(6.*m.*x1)+((m.^2).*(3-m))); %derivative of camber line 0 to m

dy_cam_2 = -(1./6).*k1.*(m.^3).*ones(1,length(x2)); %derivative of camber line m to 1

dy_cam = [dy_cam_1 dy_cam_2]; %merged derivative of camber line

theta = atan(dy_cam); %slope of camber line

y_t = 5.*t.*((0.29690.*sqrt(x))-(0.12600.*x)-(0.35160.*(x.^2)) +(0.28430.*(x.^3))-(0.10150.*(x.^4))); %thickness equation

x_upper = x-(y_t.*sin(theta)); %x coordinates of upper surface

x_lower = x+(y_t.*sin(theta)); %x coordinates of lower surface

y_upper = y_cam+(y_t.*cos(theta)); %y coordinates of upper surface

y_lower = y_cam-(y_t.*cos(theta)); %y coordinates of lower surface

%end points to close off the trailing edge

x_end_up = x_upper(end);

x_end_low = x_lower(end);

y_end_up = y_upper(end);

y_end_low = y_lower(end);

dy_cam_005 = (1./6)*k1*((3*(0.005^2))-(6.*m*0.005)+((m^2).*(3-m)));; %derivative of camber line at x = 0.005

theta_005 = atan(dy_cam_005); %slope of camber line at x = 0.005

h = r*cos(theta_005); %center of nose circle x direction

k = r*sin(theta_005); %center of nose circle y direction

x_circ = linspace(h-r,h+r,100); %x coordinates of nose circle

y_circ_upper = sqrt((r.^2)-((x_circ-h).^2))+k; %y coordinates upper half circle

y_circ_lower = -sqrt((r.^2)-((x_circ-h).^2))+k; %y coordinates lower half circle

figure

hold on

% plot(x,y_cam,’k-‘)

plot(x_upper,y_upper,’k-‘)

plot(x_lower,y_lower,’k-‘)

plot([x_end_up,x_end_low],[y_end_up,y_end_low],’k-‘) % Close off blunt trailing edge

plot(x_circ,y_circ_upper,’k-‘)

plot(x_circ,y_circ_lower,’k-‘)

hold off

slim([-0.1 1.1])

slim([-0.2 0.2])

label(‘x/c’)

label(‘y/c’)

x0=5;

y0=5;

width=500;

height=180;

set(gcf,’units’,’points’,’position’,[x0,y0,width,height])

Summary & Closure

Using the most suitable airfoil section or sections is crucial to the success of wing design, whether for subsonic, transonic, or supersonic applications, as well as other concepts such as rotary-wing designs and UAVs. To this end, various airfoil sections have been geometrically tailored to achieve the best aerodynamic performance in specific flight conditions, such as cruise flight at the highest possible airspeed and Mach number. For example, thicker, more cambered airfoils with rounded noses are better suited to slower flight speeds and low Mach numbers. In contrast, thin airfoils with sharp leading edges are ideal for high speeds and supersonic Mach numbers. Special supercritical airfoil sections have been developed for transonic flight conditions, where many airliners operate. These sections reduce wave drag and prevent boundary-layer separation behind the shock wave, enabling airliners to cruise more efficiently at speeds closer to the speed of sound.

At low Reynolds numbers, typical of small UAVs and certain atmospheric flight conditions, the aerodynamic performance requirements differ significantly from those at higher Reynolds numbers. Conventional airfoils may experience early flow separation, leading to high drag and poor lift performance. Low-Reynolds-number airfoils are specifically designed to operate efficiently under these conditions. Thin plates, in particular, can outperform conventional airfoils in these conditions by delaying flow separation and promoting reattachment. Helicopter airfoils, or rotor blades, face unique aerodynamic challenges because of the widely varying flow conditions they encounter, necessitating designs that optimize performance in both hover and forward flight. Likewise, propeller blade sections must be designed to accommodate the variable Mach number and chord Reynolds number across the blade span.

5-Question Self-Assessment Quickquiz

For Further Thought or Discussion

- Conduct research on laminar flow airfoil sections. What geometric features are incorporated into these airfoils to produce laminar flow over the surfaces?

- What airfoil shapes will likely be used for supersonic flight? Are there any NACA supersonic airfoil sections?

- Research the types of airfoils used on propeller blades. Why are different airfoils with different thicknesses along the blade span used on propellers?

- What airfoils are likely to be used on wind turbines, and why?

- What are the main parameters used to describe the geometry of an airfoil section?

- Can you describe the concept of the chord line and camber of an airfoil section?

Other Useful Online Resources

There are many more resources on airfoils to explore:

- All about airfoils on Wikipedia.

- The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has compiled airfoil coordinates and related links. Here is the guide to many uses from the UIUC Airfoil Data site.

- Visit this site for some interesting airfoil drawing tools.

- A NASA site is about how the shape of an airfoil affects lift.

- YouTube video on how airfoil shapes can affect lift generation.

- Airfoil shape basics video on YouTube.

- Information about grids and CFD calculations about airfoils.

- Learn about Richard Witcomb’s contributions to transonic airfoil design here.

- Taken from "Aeronautical & Miscellaneous NoteBook of Sir George Cayley," Cambridge University Press, 1933. ↵

- But consideration of flight at small scales and low Reynolds numbers less than 10

suggests that thin airfoil profiles have better aerodynamic characteristics than thicker airfoils. ↵

- Bocci, A. J., "A New Series of Airfoil Sections Suitable for Airplane Propellers," Aeronautical Quarterly, February 1977, pp. 59–73. ↵

- Composite materials allow for a high degree of latitude in the design of the blade shapes. ↵