1 United States

13 equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white. There is a blue rectangle in the upper hoist-side corner bearing 50 small, white, 5-pointed stars arranged in 9 offset horizontal rows of 6 stars (top and bottom) alternating with rows of 5 stars. The 50 stars represent the 50 states, the 13 stripes represent the 13 original colonies. Blue stands for loyalty, devotion, truth, justice, and friendship, red symbolizes courage, zeal, and fervency, while white denotes purity and rectitude of conduct. Commonly referred to by its nickname of Old Glory.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Stalactites and stalagmites, made of travertine, can be seen on the Frozen Niagara tour of Mammoth Cave in Kentucky. Travertine, or traveling stone, is made of limestone that has crystalized out of dripping water.

Photo Courtesy of CIA World Factbook

US Government – Constitution – Amendments – Branches

According to Britannica, the Constitution of the United States, written to redress the deficiencies of the country’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation (1781-89), defines a federal system of government in which certain powers are delegated to the national government and others are reserved to the states. The national government consists of executive, legislative, and judicial branches that are designed to ensure, through separation of powers and through checks and balances, that no one branch of government is able to subordinate the other two branches. All three branches are interrelated, each with overlapping yet quite distinct authority.

The US Constitution, the world’s oldest written national constitution still in effect, was officially ratified on June 21, 1788 (when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the document), and formally entered into force on March 4, 1789, when George Washington was sworn in as the country’s first president. Although the Constitution contains several specific provisions (such as age and residency requirements for holders of federal offices and powers granted to Congress), it is vague in many areas and could not have comprehensively addressed the complex myriad of issues (e.g., historical, technological, etc.) that have arisen in the centuries since its ratification. Thus, the Constitution is considered a living document, its meaning changing over time as a result of new interpretations of its provisions. In addition, the framers allowed for changes to the document, outlining in Article V the procedures required to amend the Constitution. Amending the Constitution requires a proposal by a two-thirds vote of each house of Congress or by a national convention called for at the request of the legislatures of two-thirds of the states, followed by ratification by three-fourths of the state legislatures or by conventions in as many states.

In the more than two centuries since the Constitution’s ratification, there have been 27 amendments. All successful amendments have been proposed by Congress, and all but one, the Twenty-First Amendment (1933), which repealed Prohibition, have been ratified by state legislatures. The first 10 amendments, proposed by Congress in September 1789 and adopted in 1791, are known collectively as the Bill of Rights, which places limits on the federal government’s power to curtail individual freedoms.

The First Amendment provides that Congress make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting its free exercise. It protects freedom of speech, the press, assembly, and the right to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

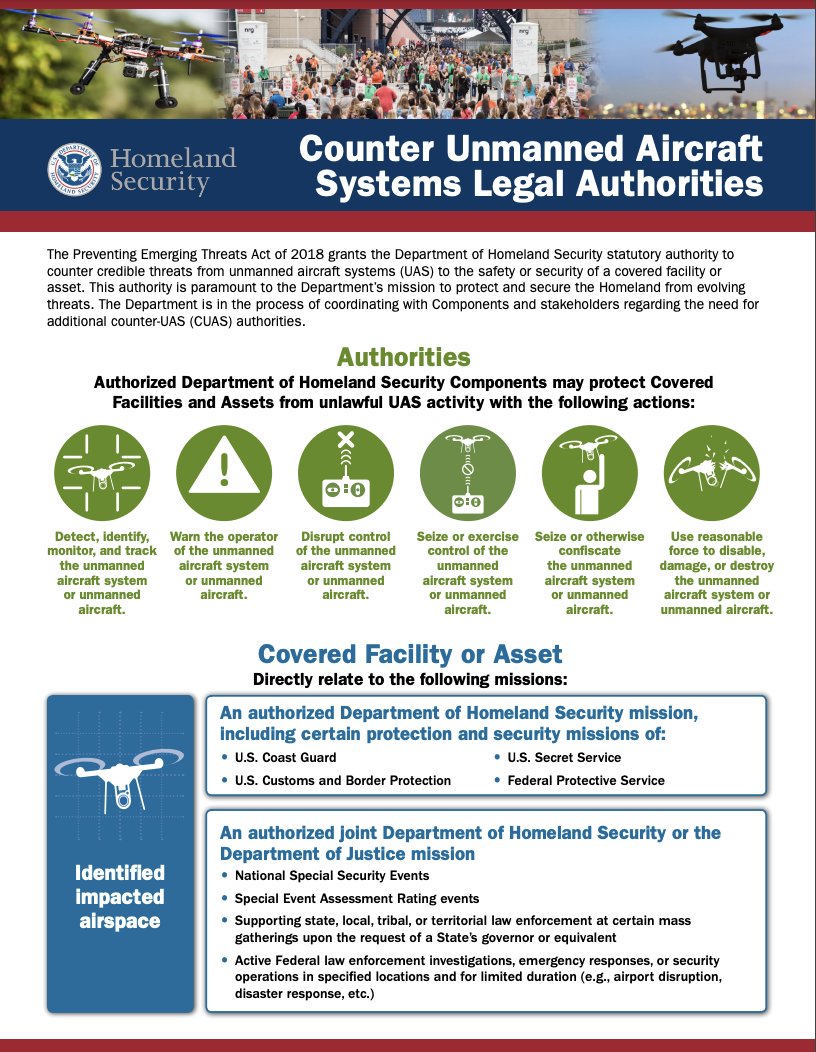

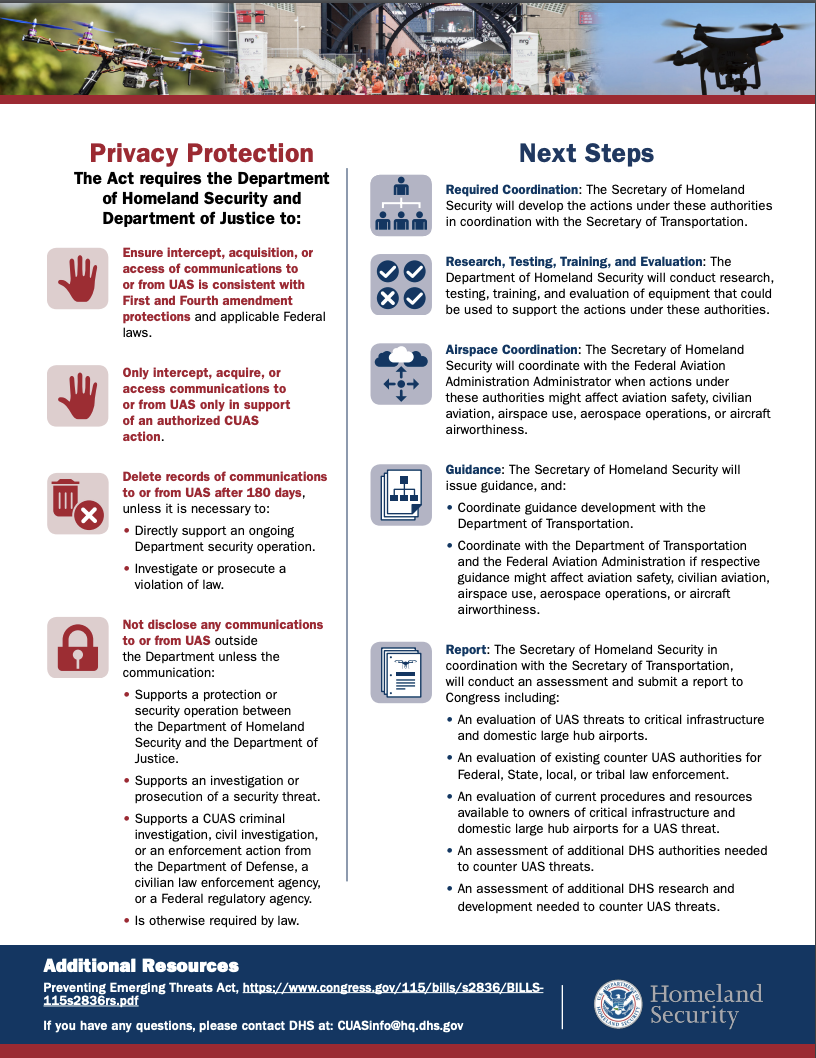

Secure Your Drone: Privacy and Data Protection Guidance – Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) developed this guidance to equip drone users and stakeholders with recommendations to protect their data and minimize privacy risks before, during, and after flying their drone. The guidance also includes an overview of the connected components of a drone – components that gather and communicate information via the internet or Bluetooth and are vulnerable to exploitation. Lastly, the guidance points to additional tools and resources, such as cybersecurity best practices, FAA information, and reporting recommendations.- 2023

The guarantees of the Bill of Rights are steeped in controversy, and debate continues over the limits that the federal government may appropriately place on individuals. One source of conflict has been the ambiguity in the wording of many of the Constitution’s provisions, such as the Second Amendment’s right “to keep and bear arms” and the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishments.” Also problematic is the Tenth Amendment’s apparent contradiction of the body of the Constitution; Article I, Section 8, enumerates the powers of Congress but also allows that it may make all laws “which shall be necessary and proper,” while the Tenth Amendment stipulates that “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” The distinction between what powers should be left to the states or to the people and what is a necessary and proper law for Congress to pass has not always been clear.

Between the ratification of the Bill of Rights and the American Civil War (1861–65), only two amendments were passed, and both were technical in nature. The Eleventh Amendment (1795) forbade suits against the states in federal courts, and the Twelfth Amendment (1804) corrected a constitutional error that came to light in the presidential election of 1800, when Democratic-Republicans Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr each won 73 electors because electors were unable to cast separate ballots for president and vice president. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments were passed in the aftermath of the Civil War. The Thirteenth (1865) abolished slavery, while the Fifteenth (1870) forbade denial of the right to vote to formerly enslaved men. The Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship rights to formerly enslaved people and guaranteed to every citizen due process and equal protection of the laws, was regarded for a while by the courts as limiting itself to the protection of formerly enslaved people, but it has since been used to extend protections to all citizens. Initially, the Bill of Rights applied solely to the federal government and not to the states. In the 20th century, however, many (though not all) of the provisions of the Bill of Rights were extended by the Supreme Court through the Fourteenth Amendment to protect individuals from encroachments by the states.

Notable amendments since the Civil War include the Sixteenth (1913), which enabled the imposition of a federal income tax; the Seventeenth (1913), which provided for the direct election of US senators; the Nineteenth (1920), which established woman suffrage; the Twenty-fifth (1967), which established succession to the presidency and vice presidency; and the Twenty-sixth (1971), which extended voting rights to all citizens 18 years of age or older.

The executive branch is headed by the president, who must be a natural-born citizen of the US, at least 35 years old, and a resident of the country for at least 14 years. A president is elected indirectly by the people through the Electoral College system to a four-year term and is limited to two elected terms of office by the Twenty-second Amendment (1951). The president’s official residence and office is the White House, located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W. in Washington, D.C. The formal constitutional responsibilities vested in the presidency of the US include serving as commander in chief of the armed forces; negotiating treaties; appointing federal judges, ambassadors, and cabinet officials; and acting as head of state. In practice, presidential powers have expanded to include drafting legislation, formulating foreign policy, conducting personal diplomacy, and leading the president’s political party.

The members of the president’s cabinet, the attorney general and the secretaries of State, Treasury, Defense, Homeland Security, Interior, Agriculture, Commerce, Labor, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, Transportation, Education, Energy, and Veterans Affairs, are appointed by the president with the approval of the Senate; although they are described in the Twenty-fifth Amendment as “the principal officers of the executive departments,” significant power has flowed to non-cabinet-level presidential aides, such as those serving in the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the Council of Economic Advisers, the National Security Council (NSC), and the office of the White House Chief of Staff; cabinet-level rank may be conferred to the heads of such institutions at the discretion of the president. Members of the cabinet and presidential aides serve at the pleasure of the president and may be dismissed by him at any time.

The executive branch also includes independent regulatory agencies such as the Federal Reserve System and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Governed by commissions appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate (commissioners may not be removed by the president), these agencies protect the public interest by enforcing rules and resolving disputes over federal regulations. Also part of the executive branch are government corporations (e.g., the Tennessee Valley Authority, the National Railroad Passenger Corporation [Amtrak], and the US Postal Service), which supply services to consumers that could be provided by private corporations, and independent executive agencies (e.g., the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Science Foundation, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration), which comprise the remainder of the federal government.

The US Congress, the legislative branch of the federal government, consists of two houses: the Senate and the House of Representatives. Powers granted to Congress under the Constitution include the power to levy taxes, borrow money, regulate interstate commerce, impeach and convict the president, declare war, discipline its own membership, and determine its rules of procedure.

With the exception of revenue bills, which must originate in the House of Representatives, legislative bills may be introduced in and amended by either house, and a bill, with its amendments, must pass both houses in identical form and be signed by the president before it becomes law. The president may veto a bill, but a veto can be overridden by a two-thirds vote of both houses. The House of Representatives may impeach a president or another public official by a majority vote; trials of impeached officials are conducted by the Senate, and a two-thirds majority is necessary to convict and remove the individual from office. Congress is assisted in its duties by the General Accounting Office (GAO), which examines all federal receipts and expenditures by auditing federal programs and assessing the fiscal impact of proposed legislation, and by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), a legislative counterpart to the OMB, which assesses budget data, analyzes the fiscal impact of alternative policies, and makes economic forecasts.

The House of Representatives is chosen by the direct vote of the electorate in single-member districts in each state. The number of representatives allotted to each state is based on its population as determined by a decennial census; states sometimes gain or lose seats, depending on population shifts. The overall membership of the House has been 435 since the 1910s, though it was temporarily expanded to 437 after Hawaii and Alaska were admitted as states in 1959. Members must be at least 25 years old, residents of the states from which they are elected, and previously citizens of the United States for at least seven years. It has become a practical imperative, though not a constitutional requirement, that a member be an inhabitant of the district that elects him. Members serve two-year terms, and there is no limit on the number of terms they may serve. The speaker of the House, who is chosen by the majority party, presides over debate, appoints members of select and conference committees, and performs other important duties; he is second in the line of presidential succession (following the vice president). The parliamentary leaders of the two main parties are the majority floor leader and the minority floor leader. The floor leaders are assisted by party whips, who are responsible for maintaining contact between the leadership and the members of the House. Bills introduced by members in the House of Representatives are received by standing committees, which can amend, expedite, delay, or kill legislation. Each committee is chaired by a member of the majority party, who traditionally attained this position on the basis of seniority, though the importance of seniority has eroded somewhat since the 1970s. Among the most important committees are those on Appropriations, Ways and Means, and Rules. The Rules Committee, for example, has significant power to determine which bills will be brought to the floor of the House for consideration and whether amendments will be allowed on a bill when it is debated by the entire House.

Each state elects two senators at large. Senators must be at least 30 years old, residents of the state from which they are elected, and previously citizens of the United States for at least nine years. They serve six-year terms, which are arranged so that one-third of the Senate is elected every two years. Senators also are not subject to term limits. The vice president serves as president of the Senate, casting a vote only in the case of a tie, and in his absence the Senate is chaired by a president pro tempore, who is elected by the Senate and is third in the line of succession to the presidency. Among the Senate’s most prominent standing committees are those on Foreign Relations, Finance, Appropriations, and Governmental Affairs. Debate is almost unlimited and may be used to delay a vote on a bill indefinitely. Such a delay, known as a filibuster, can be ended by three-fifths of the Senate through a procedure called cloture. Treaties negotiated by the president with other governments must be ratified by a two-thirds vote of the Senate. The Senate also has the power to confirm or reject presidentially appointed federal judges, ambassadors, and cabinet officials.

The judicial branch is headed by the Supreme Court of the United States, which interprets the Constitution and federal legislation. The Supreme Court consists of nine justices (including a chief justice) appointed to life terms by the president with the consent of the Senate. It has appellate jurisdiction over the lower federal courts and over state courts if a federal question is involved. It also has original jurisdiction (i.e., it serves as a trial court) in cases involving foreign ambassadors, ministers, and consuls and in cases to which a US state is a party.

Most cases reach the Supreme Court through its appellate jurisdiction. The Judiciary Act of 1925 provided the justices with the sole discretion to determine their caseload. In order to issue a writ of certiorari, which grants a court hearing to a case, at least four justices must agree (the “Rule of Four”). Three types of cases commonly reach the Supreme Court: cases involving litigants of different states, cases involving the interpretation of federal law, and cases involving the interpretation of the Constitution. The court can take official action with as few as six judges joining in deliberation, and a majority vote of the entire court is decisive; a tie vote sustains a lower-court decision. The official decision of the court is often supplemented by concurring opinions from justices who support the majority decision and dissenting opinions from justices who oppose it.

Because the Constitution is vague and ambiguous in many places, it is often possible for critics to fault the Supreme Court for misinterpreting it. In the 1930s, for example, the Republican-dominated court was criticized for overturning much of the New Deal legislation of Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the area of civil rights, the court has received criticism from various groups at different times. Its 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which declared school segregation unconstitutional, was harshly attacked by Southern political leaders, who were later joined by Northern conservatives. A number of decisions involving the pretrial rights of prisoners, including the granting of Miranda rights and the adoption of the exclusionary rule, also came under attack on the ground that the court had made it difficult to convict criminals. On divisive issues such as abortion, affirmative action, school prayer, and flag burning, the court’s decisions have aroused considerable opposition and controversy, with opponents sometimes seeking constitutional amendments to overturn the court’s decisions.

At the lowest level of the federal court system are district courts. Each state has at least one federal district court and at least one federal judge. District judges are appointed to life terms by the president with the consent of the Senate. Appeals from district-court decisions are carried to the US courts of appeals. Losing parties at this level may appeal for a hearing from the Supreme Court. Special courts handle property and contract damage suits against the United States (United States Court of Federal Claims), review customs rulings (United States Court of International Trade), hear complaints by individual taxpayers (United States Tax Court) or veterans (United States Court of Appeals for Veteran Claims), and apply the Uniform Code of Military Justice (United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces).

Because the US Constitution establishes a federal system, the state governments enjoy extensive authority. The Constitution outlines the specific powers granted to the national government and reserves the remainder to the states. However, because of ambiguity in the Constitution and disparate historical interpretations by the federal courts, the powers actually exercised by the states have waxed and waned over time. Beginning in the last decades of the 20th century, for example, decisions by conservative-leaning federal courts, along with a general trend favoring the decentralization of government, increased the power of the states relative to the federal government. In some areas, the authority of the federal and state governments overlap; for example, the state and federal governments both have the power to tax, establish courts, and make and enforce laws. In other areas, such as the regulation of commerce within a state, the establishment of local governments, and action on public health, safety, and morals, the state governments have considerable discretion. The Constitution also denies to the states certain powers; for example, the Constitution forbids states to enter into treaties, to tax imports or exports, or to coin money. States also may not adopt laws that contradict the US Constitution.

The governments of the 50 states have structures closely paralleling those of the federal government. Each state has a governor, a legislature, and a judiciary. Each state also has its own constitution.

Mirroring the US Congress, all state legislatures are bicameral except Nebraska’s, which is unicameral. Most state judicial systems are based upon elected justices of the peace (although in many states this term is not used), above whom are major trial courts, often called district courts, and appellate courts. Each state has its own supreme court. In addition, there are probate courts concerned with wills, estates, and guardianships. Most state judges are elected, though some states use an appointment process similar to the federal courts and some use a nonpartisan selection process known as the Missouri Plan.

State governors are directly elected and serve varying terms (generally ranging from two to four years); in some states, the number of terms a governor may serve is limited. The powers of governors also vary, with some state constitutions ceding substantial authority to the chief executive (such as appointment and budgetary powers and the authority to veto legislation). In a few states, however, governors have highly circumscribed authority, with the constitution denying them the power to veto legislative bills.

Most states have a lieutenant governor, who is often elected independently of the governor and is sometimes not a member of the governor’s party. Lieutenant governors generally serve as the presiding officer of the state Senate. Other elected officials commonly include a secretary of state, state treasurer, state auditor, attorney general, and superintendent of public instruction.

State governments have a wide array of functions, encompassing conservation, highway and motor vehicle supervision, public safety and corrections, professional licensing, regulation of agriculture and of intrastate business and industry, and certain aspects of education, public health, and welfare. The administrative departments that oversee these activities are headed by the governor.

Each state may establish local governments to assist it in carrying out its constitutional powers. Local governments exercise only those powers that are granted to them by the states, and a state may redefine the role and authority of local government as it deems appropriate. The country has a long tradition of local democracy (e.g., the town meeting), and even some of the smallest areas have their own governments. There are some 85,000 local government units in the United States. The largest local government unit is the county (called a parish in Louisiana or a borough in Alaska). Counties range in population from as few as 100 people to millions (e.g., Los Angeles county). They often provide local services in rural areas and are responsible for law enforcement and keeping vital records. Smaller units include townships, villages, school districts, and special districts (e.g., housing authorities, conservation districts, and water authorities).

Municipal, or city, governments are responsible for delivering most local services, particularly in urban areas. At the beginning of the 21st century there were some 20,000 municipal governments in the United States. They are more diverse in structure than state governments. There are three basic types: mayor-council, commission, and council-manager governments. The mayor-council form, which is used in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago, and thousands of smaller cities, consists of an elected mayor and council. The power of mayors and councils vary from city to city; in most cities the mayor has limited powers and serves largely as a ceremonial leader, but in some cities (particularly large urban areas) the council is nominally responsible for formulating city ordinances, which the mayor enforces, but the mayor often controls the actions of the council. In the commission type, used less frequently now than it was in the early 20th century, voters elect a number of commissioners, each of whom serves as head of a city department; the presiding commissioner is generally the mayor. In the council-manager type, used in large cities such as Charlotte (North Carolina), Dallas (Texas), Phoenix (Arizona), and San Diego (California), an elected council hires a city manager to administer the city departments. The mayor, elected by the council, simply chairs the council and officiates at important functions.

As society has become increasingly urban, politics and government have become more complex. Many problems of the cities, including transportation, housing, education, health, and welfare, can no longer be handled entirely on the local level. Because even the states do not have the necessary resources, cities have often turned to the federal government for assistance, though proponents of local control have urged that the federal government provide block-grant aid to state and local governments without federal restrictions.

The framers of the US Constitution focused their efforts primarily on the role, power, and function of the state and national governments, only briefly addressing the political and electoral process. Indeed, three of the Constitution’s four references to the election of public officials left the details to be determined by Congress or the states. The fourth reference, in Article II, Section 1, prescribed the role of the Electoral College in choosing the president, but this section was soon amended (in 1804 by the Twelfth Amendment) to remedy the technical defects that had arisen in 1800, when all Democratic-Republican Party electors cast their votes for Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, thereby creating a tie because electors were unable to differentiate between their presidential and vice presidential choices. (The election of 1800 was finally settled by Congress, which selected Jefferson president following 36 ballots.)

In establishing the Electoral College, the framers stipulated that “Congress may determine the Time of chusing [sic] the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.” In 1845 Congress established that presidential electors would be appointed on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November; the electors cast their ballots on the Monday following the second Wednesday in December. Article I, establishing Congress, merely provides (Section 2) that representatives are to be “chosen every second Year by the People of the several States” and that voting qualifications are to be the same for Congress as for the “most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.” Initially, senators were chosen by their respective state legislatures (Section 3), though this was changed to popular election by the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913. Section 4 leaves to the states the prescription of the “Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives” but gives Congress the power “at any time by Law [to] make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.” In 1875 Congress designated the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November in even years as federal election day.

This table below summarizes the three branches of US Government

| Executive branch | Legislative branch | Judicial branch |

| POTUS issues:

Executive Orders Presidential Memoranda Proclamations Published in Federal Register |

2 chambers – house and senate

House – 435 members elected Senate 100 members elected Several committees and subcommittees perform the work creating bills that become law |

SCOTUS – supreme law of the land

Courts of Appeal (13) Federal District Courts (94)

|

| US Constitution Article II Section 3 | US Constitution Article I | US Constitution Article III Section 1 |

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

The Civil Aviation Authority for the US is the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

You may find a brief history of the FAA quite fascinating!

The FAA provides air traffic services for the NAS.

The FAA has a Dynamic Regulatory System which is a comprehensive knowledge center of regulatory and guidance material from the Office of Aviation Safety and other Services and Offices.

Drone regulations may be found on the FAA UAS Web Pages.

Penalties, under Administrative Law, for violating these regulations may be found in FAA Order 2150.3 FAA Compliance and Enforcement Program

The FAA also has a YouTube channel for useful drone videos!

The FAA has the authority to create a comprehensive regulatory system governing the safe and efficient management of UAS and AAM operations, including non-commercial operations at ground-level altitudes, above private property, and within state boundaries following the laws Congress has passed under its Constitutional Commerce Clause powers.

In addition, following the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, the state and local laws affecting the field of aviation safety and the efficient use of airspace are federally preempted, (FAA Office of the Chief Counsel, State and Local Regulation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems UAS Fact Sheet), although non-federal government entities may still issue specific laws pertaining to UAS that do not touch this federally preempted field.

The US DOT has communicated it is the FAA’s “long-held position that . . . [FAA] has the responsibility to regulate aviation safety and the efficiency of the airspace within the navigable airspace, which may extend down to the ground.” This authority and responsibility to regulate all aircraft operations down to the ground are based in part on 49 U.S.C. § 40103(b)(1), from Congress’s Air Commerce Act of 1926 legislation enacted in the context of crewed aircraft. As currently codified, that provision authorizes the FAA to regulate “the use of the navigable airspace . . . to ensure the safety of aircraft and the efficient use of [that] airspace,” and “navigable airspace” is defined as the airspace above minimum safe flight altitudes prescribed by FAA regulations.

Although the FAA has not issued regulations prescribing minimum safe flight altitudes for UAS or AAM, DOT officials have told the Government Accountability Office in interviews, “It is the Department’s stance that, for purposes of the definition of the term navigable airspace, zero feet (‘the blades of grass’) is the minimum altitude of flight for UAS.” (Government Accountability Office, 2020.) UAS operations at ground level also are supported by 49 U.S.C. § 44701(a)(5) which directs the FAA to issue “air commerce” safety regulations. The officials noted that because “air commerce,” in contrast to “navigable airspace,” is not defined by a minimum altitude, FAA may regulate UAS and other “aircraft” in the stream of interstate commerce even when they are on the ground. Support also comes from 49 U.S.C. § 40103(b)(2), which among other things directs FAA to issue air traffic regulations for “protecting individuals and property on the ground.”

The FAA points to the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, to rule that state and local laws affecting the field of aviation safety and the efficient use of airspace are federally preempted although non-federal government entities may still issue laws and ordinances pertaining to UAS and AAM that are not in this preempted category. In particular, according to the FAA, it is responsible for air safety “from the ground up,” including for UAS and AAM operations. In addition, “navigable airspace,” “air commerce,” and “national airspace system” statutes and rules are cited by FAA as supporting its regulation of UAS and AAM operations from the ground up. The agency refers throughout the preamble to one of its UAS rulemakings to the regulation of UAS operations now as in the general “airspace of the United States” (Fed. Reg. 72438 (Dec. 31, 2019).

The Federal Aviation Act of 1958 – established that “the FAA, was passed by Congress for the purpose of centralizing in a single authority the power to frame rules for the safe and efficient use of the nation’s air space.”

Federal code 49 U.S.C. 44701(a)(5) allows the FAA to prescribe regulations and minimum standards necessary for safety in air commerce and national security,” and this allowance leaves “some room for state and local UAS laws, albeit recommending that state authorities first consult federal aviation authorities in such matters.” Jurisprudence on the Federal Aviation Act shows that where there are pervasive regulations in an area, the Federal Aviation Act preempts all state claims in that area, particularly air safety.

US National Airspace System (NAS)

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

The airspace over the USA, per ENR 1.4, contains the following two categories of airspace or airspace areas:

(1) Regulatory (Class A, B, C, D, and E airspace areas, restricted, and prohibited areas) and

(2) Non regulatory (military operations areas (MOAs), warning areas, alert areas, controlled firing areas (CFAs), and National Security Areas (NSAs).

Within these two categories there are four types:

(1) Controlled (A, B, C, D, E);

(2) Uncontrolled (G);

(3) Special Use; and

(4) Other airspace.

National Airspace System Status – Dashboard

The Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK), Chapter 15 explains in more detail.

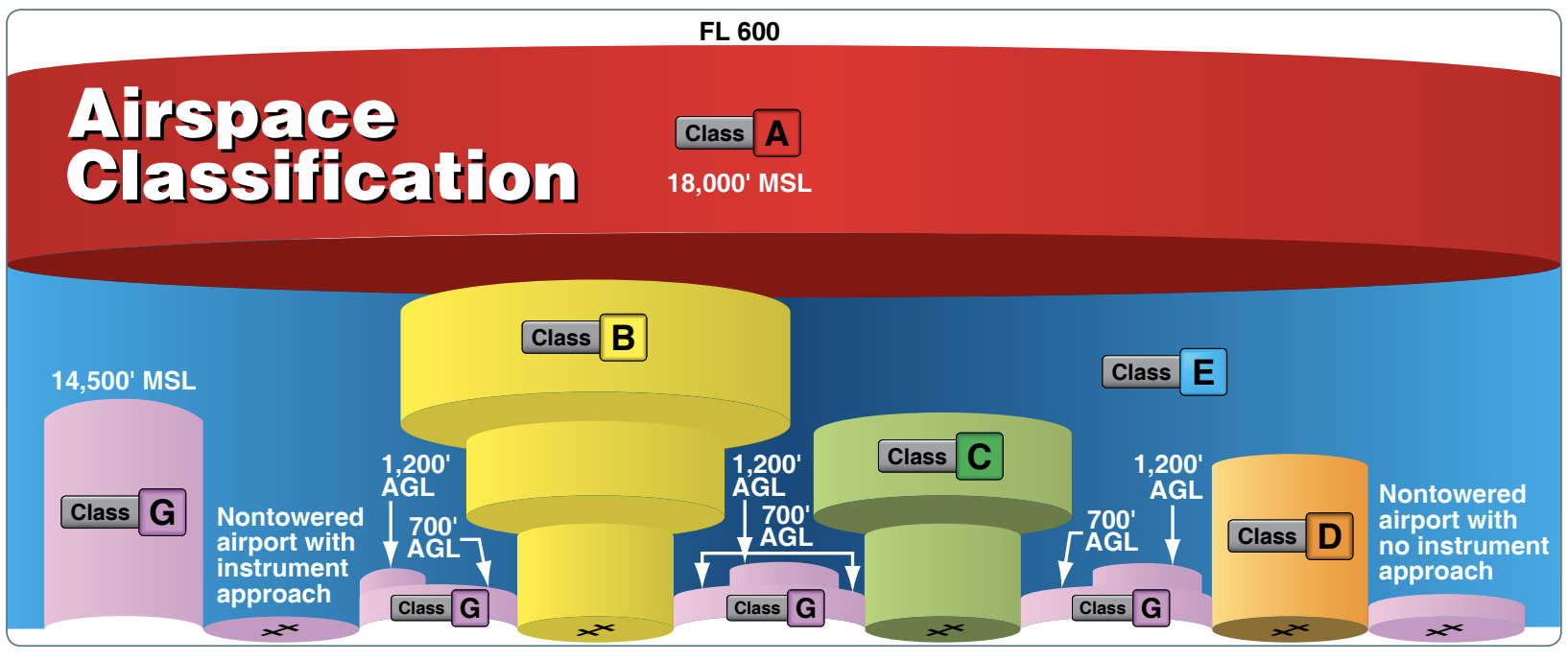

Photo from FAA PHAK, Chapter 15

Class A Airspace

Generally the airspace from 18,000 feet MSL up to and including flight level (FL) 600, including the airspace overlying the waters within 12 nautical miles (NM) of the coast of the 48 contiguous states and Alaska.

Unless otherwise authorized, all operation in Class A airspace is conducted under instrument flight rules (IFR).

Class B Airspace

Generally airspace from the surface to 10,000 feet MSL surrounding the nation’s busiest airports in terms of airport operations or passenger enplanements.

The configuration of each Class B airspace area is individually tailored, consists of a surface area and two or more layers (some Class B airspace areas resemble upside-down wedding cakes), and is designed to contain all published instrument procedures once an aircraft enters the airspace.

ATC clearance is required for all aircraft to operate in the area, and all aircraft that are so cleared receive separation services within the airspace.

Class C Airspace

Generally airspace from the surface to 4,000 feet above the airport elevation (charted in MSL) surrounding those airports that have an operational control tower, are serviced by a radar approach control, and have a certain number of IFR operations or passenger enplanements.

Although the configuration of each Class C area is individually tailored, the airspace usually consists of a surface area with a five NM radius, an outer circle with a ten NM radius that extends from 1,200 feet to 4,000 feet above the airport elevation.

Each aircraft must establish two-way radio communications with the ATC facility providing air traffic services prior to entering the airspace and thereafter must maintain those communications while within the airspace.

Class D Airspace

Generally airspace from the surface to 2,500 feet above the airport elevation (charted in MSL) surrounding those airports that have an operational control tower.

The configuration of each Class D airspace area is individually tailored and, when instrument procedures are published, the airspace is normally designed to contain the procedures.

Arrival extensions for instrument approach procedures (IAPs) may be Class D or Class E airspace.

Unless otherwise authorized, each aircraft must establish two-way radio communications with the ATC facility providing air traffic services prior to entering the airspace and thereafter maintain those communications while in the airspace.

Class E Airspace

The controlled airspace not classified as Class A, B, C, or D airspace.

A large amount of the airspace over the United States is designated as Class E airspace.

This provides sufficient airspace for the safe control and separation of aircraft during IFR operations.

Chapter 3 of the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) explains the various types of Class E airspace.

Sectional and other charts depict all locations of Class E airspace with bases below 14,500 feet MSL.

In areas where charts do not depict a class E base, class E begins at 14,500 feet MSL.

In most areas, the Class E airspace base is 1,200 feet AGL.

In many other areas, the Class E airspace base is either the surface or 700 feet AGL.

Some Class E airspace begins at an MSL altitude depicted on the charts, instead of an AGL altitude.

Class E airspace typically extends up to, but not including, 18,000 feet MSL (the lower limit of Class A airspace).

All airspace above FL 600 is Class E airspace.

Class G Airspace

Uncontrolled airspace or Class G airspace is the portion of the airspace that has not been designated as Class A, B, C, D, or E.

It is therefore designated uncontrolled airspace.

Class G airspace extends from the surface to the base of the overlying Class E airspace.

Although ATC has no authority or responsibility to control air traffic, pilots should remember there are visual flight rules (VFR) minimums that apply to Class G airspace.

Special use airspace or special area of operation (SAO) is the designation for airspace in which certain activities must be confined, or where limitations may be imposed on aircraft operations that are not part of those activities.

Certain special use airspace areas can create limitations on the mixed use of airspace.

The special use airspace depicted on instrument charts includes the area name or number, effective altitude, time and weather conditions of operation, the controlling agency, and the chart panel location.

On National Aeronautical Charting Group (NACG) en route charts, this information is available on one of the end panels.

Special use airspace usually consists of:

• Prohibited areas

• Restricted areas

• Warning areas

• Military operation areas (MOAs)

• Alert areas

• Controlled firing areas (CFAs)

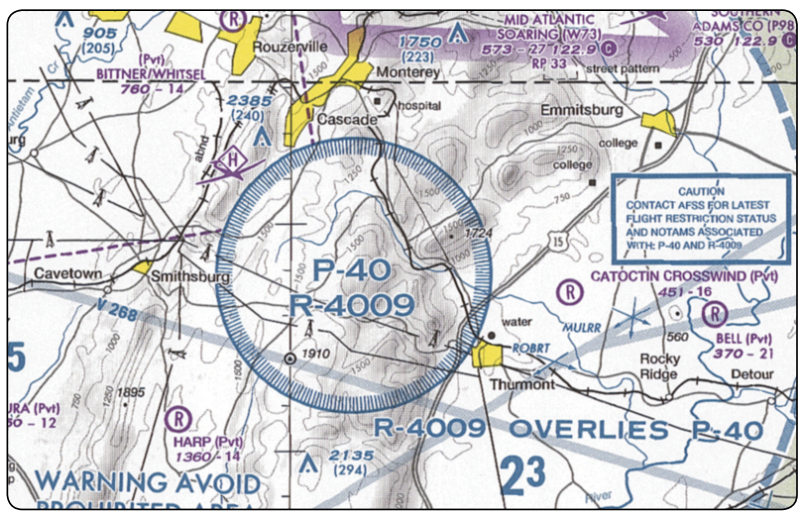

Prohibited Areas

Contain airspace of defined dimensions within which the flight of aircraft is prohibited.

Such areas are established for security or other reasons associated with the national welfare.

These areas are published in the Federal Register and are depicted on aeronautical charts.

The area is charted as a “P” followed by a number (e.g., P-40).

Examples of prohibited areas include Camp David and the National Mall in Washington, D.C., where the White House and the Congressional buildings are located.

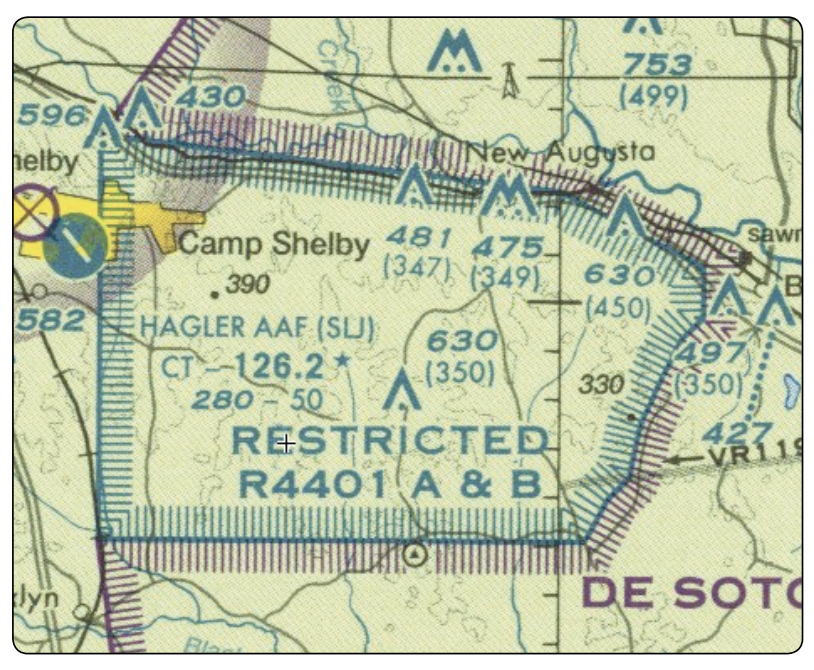

Restricted Areas

Areas where operations are hazardous to nonparticipating aircraft and contain airspace within which the flight of aircraft, while not wholly prohibited, is subject to restrictions.

Activities within these areas must be confined because of their nature, or limitations may be imposed upon aircraft operations that are not a part of those activities, or both.

Restricted areas denote the existence of unusual, often invisible, hazards to aircraft (e.g., artillery firing, aerial gunnery, or guided missiles).

IFR flights may be authorized to transit the airspace and are routed accordingly.

Penetration of restricted areas without authorization from the using or controlling agency may be extremely hazardous to the aircraft and its occupants.

ATC facilities apply the following procedures when aircraft are operating on an IFR clearance (including those cleared by ATC to maintain VFR on top) via a route that lies within joint-use restricted airspace:

1. If the restricted area is not active and has been released to the FAA, the ATC facility allows the aircraft to operate in the restricted airspace without issuing specific clearance for it to do so.

2. If the restricted area is active and has not been released to the FAA, the ATC facility issues a clearance that ensures the aircraft avoids the restricted airspace.

Restricted areas are charted with an “R” followed by a number (e.g., R-4401) and are depicted on the en route chart appropriate for use at the altitude or FL being flown.

FAA Restricted Airspace – Special Flight Rules Area (SFRA)

The Washington D.C. Metropolitan Area Special Flight Rules Area (DC SFRA) is roughly a circular area with a 30 nautical mile (about 33 statute miles) radius around Washington, D.C., and surrounds the Flight-Restricted Zone (FRZ). The Leesburg Executive Airport is located on the boundary of the SFRA. The Leesburg Maneuvering Area was developed to ease access into and out of Leesburg airport. The current Code of Federal Regulations detail proper procedures to access the area. Flight exercise operations at non-controlled tower airports within the SFRA (but not within the DC FRZ) must be conducted in accordance with 14 CFR section 93.339 (C).

There are a number of requirements for aircraft flying within the SFRA:

- Pilots must obtain an advanced clearance from FAA air traffic control to fly within, into, or out of the SFRA.

- Aircraft flying within the SFRA must have an altitude-encoding transponder and it must be operating.

- FAA air traffic control must assign a four-digit number that identifies the aircraft by call sign or registration number when it gives a pilot clearance to fly in the SFRA.

- While flying within the SFRA, the pilot must be in direct contact with air traffic control unless cleared to the local airport traffic advisory frequency.

The Flight-Restricted Zone (FRZ) extends approximately 15 nautical miles (about 17 statute miles) around Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. The airport is located in Arlington County, VA, four miles from downtown Washington, D.C. The FRZ has been in effect since September 11, 2001.

The only non-governmental flights allowed within the FRZ without a waiver are scheduled commercial flights into and out of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. Airlines operating charter flights that support the U.S. government may land at Joint Base Andrews Air Force Base or Ronald Reagan Washington National Airports without a waiver and under certain conditions per FDC NOTAM 8/3032.

Certain general aviation flights may be authorized to fly within the FRZ.

Waiver applications and Transportation Security Administration (TSA) authorizations

Pilots who have been vetted by the TSA are allowed to fly in and out of the three Maryland general aviation airports. Other commercial air carrier flights can be vectored into the FRZ by air traffic controllers. Some approved news and traffic-reporting aircraft are allowed to operate under certain conditions within the FRZ. Contact TSA Maryland Three Program mdthree@tsa.dhs.gov for any questions.

Prohibited Area 56 (P-56) – P-56A & B – are prohibited areas surrounding the White House, the National Mall, and the vice president’s residence in Washington, D.C. The only aircraft that are allowed to fly within these prohibited areas are specially authorized flights that are in direct support of the U.S. Secret Service, the Office of the President, or one of several government agencies with missions that require air support within P-56. These prohibited areas have been in effect for about 50 years.

P-56A covers approximately the area west of the Lincoln Memorial (Rock Creek Park) to east of the Capitol (Stanton Square) and between Independence Avenue and K Street up to 18,000 feet.

P-56B covers a small circle with a radius of about one nautical mile (about 1.2 statute miles) surrounding the Naval Observatory on Massachusetts Avenue up to 18,000 feet.

Visual Warning System for the SFRA – In some situations, NORAD (the North American Aerospace Defense Command) uses a warning signal to communicate with pilots who fly into the SFRA or FRZ without authorization. The signal uses highly focused red and green lights in an alternating red/ red/green signal pattern. This signal is directed at specific aircraft suspected of making unauthorized entry into the SFRA/FRZ that are on a heading or flight path that may be interpreted as a threat, or that operate contrary to the operating rules for the SFRA/FRZ.

The beam will not injure the eyes of pilots, aircrews or passengers, regardless of altitude or distance from the source.

If pilots are in communication with air traffic control and this signal is directed at their aircraft, they are advised to immediately tell air traffic control that they are being illuminated by a visual-warning signal. If this signal is directed at a pilot who is not communicating with air traffic control, that pilot should turn to a heading away from the center of the FRZ/SFRA as soon as possible and immediately contact air traffic control on an appropriate frequency. If a pilot is unsure of the frequency, he or she should contact air traffic control on VHF guard frequency 121.5 or UHF guard 243.0.

Failure to follow these procedures may result in interception by military aircraft and/or the use of force. This applies to all aircraft operating within the SFRA, including Department of Defense, law enforcement, and aeromedical operations.

FAASTeam Course ALC-405 – Free course

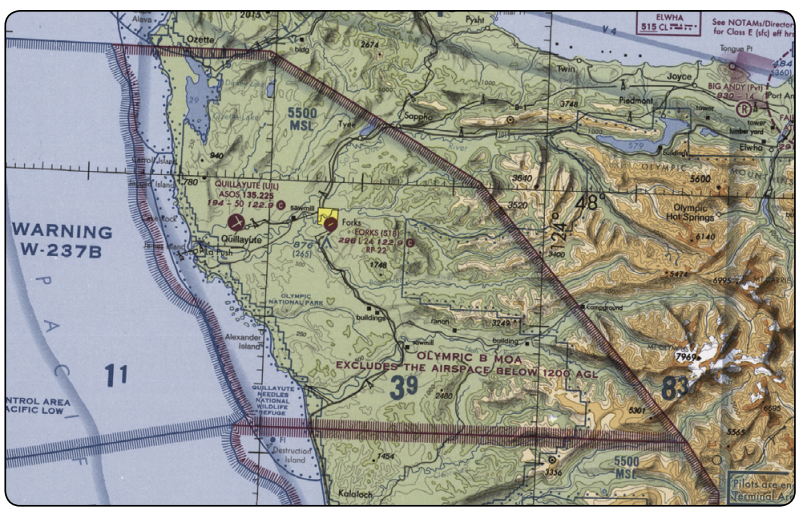

Warning Areas

Similar in nature to restricted areas; however, the US government does not have sole jurisdiction over the airspace.

A warning area is airspace of defined dimensions, extending from 3 NM outward from the coast of the United States, containing activity that may be hazardous to nonparticipating aircraft.

The purpose of such areas is to warn nonparticipating pilots of the potential danger.

A warning area may be located over domestic or international waters or both.

The airspace is designated with a “W” followed by a number (e.g., W-237).

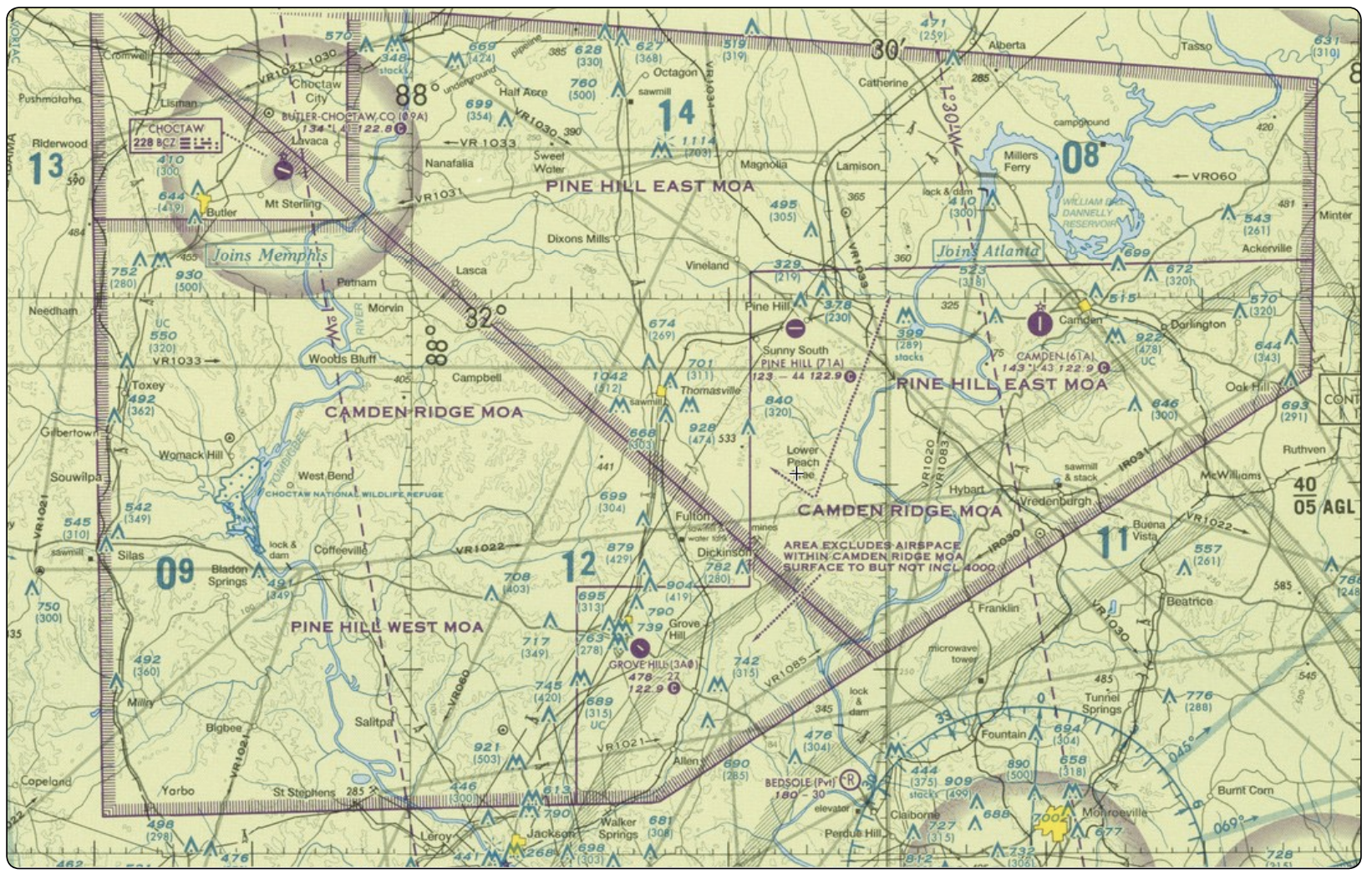

Military Operation Areas (MOAs)

MOAs consist of airspace with defined vertical and lateral limits established for the purpose of separating certain military training activities from IFR traffic.

Whenever an MOA is being used, nonparticipating IFR traffic may be cleared through an MOA if IFR separation can be provided by ATC. Otherwise, ATC reroutes or restricts nonparticipating IFR traffic.

MOAs are depicted on sectional, VFR terminal area, and en route low altitude charts and are not numbered (e.g., “Camden Ridge MOA”).

However, the MOA is also further defined on the back of the sectional charts with times of operation, altitudes affected, and the controlling agency.

Alert Areas

Depicted on aeronautical charts with an “A” followed by a number (e.g., A-211) to inform nonparticipating pilots of areas that may contain a high volume of pilot training or an unusual type of aerial activity.

Pilots should exercise caution in alert areas.

All activity within an alert area shall be conducted in accordance with regulations, without waiver, and pilots of participating aircraft, as well as pilots transiting the area, shall be equally responsible for collision avoidance.

Controlled Firing Areas (CFAs)

CFAs contain activities that, if not conducted in a controlled environment, could be hazardous to nonparticipating aircraft.

The difference between CFAs and other special use airspace is that activities must be suspended when a spotter aircraft, radar, or ground lookout position indicates an aircraft might be approaching the area.

There is no need to chart CFAs since they do not cause a nonparticipating aircraft to change its flight path.

General term referring to the majority of the remaining airspace.

It includes:

• Local airport advisory (LAA)

• Military training route (MTR)

• Temporary flight restriction (TFR)

• Parachute jump aircraft operations

• Published VFR routes

• Terminal radar service area (TRSA)

• National security area (NSA)

• Air Defense Identification Zones (ADIZ) land and water based and need for Defense VFR (DVFR) flight plan to operate VFR in this airspace

• Intercept Procedures and use of 121.5 for communication if not on ATC already Flight Restricted Zones (FRZ) in vicinity of Capitol and White House

• Special Awareness Training required by 14 CFR 91.161 for pilots to operate VFR within 60 NM of the Washington, DC VOR/DME

• Wildlife Areas/Wilderness Areas/National Parks and request to operate above 2,000 AGL

• National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Areas off the coast with requirement to operate above 2,000 AGL

• Tethered Balloons for observation and weather recordings that extend on cables up to 60,000

Local Airport Advisory (LAA)

An advisory service provided by Flight Service Station (FSS) facilities, which are located on the landing airport, using a discrete ground-to-air frequency or the tower frequency when the tower is closed.

LAA services include local airport advisories, automated weather reporting with voice broadcasting, and a continuous Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS)/Automated Weather Observing Station (AWOS) data display, other continuous direct reading instruments, or manual observations available to the specialist.

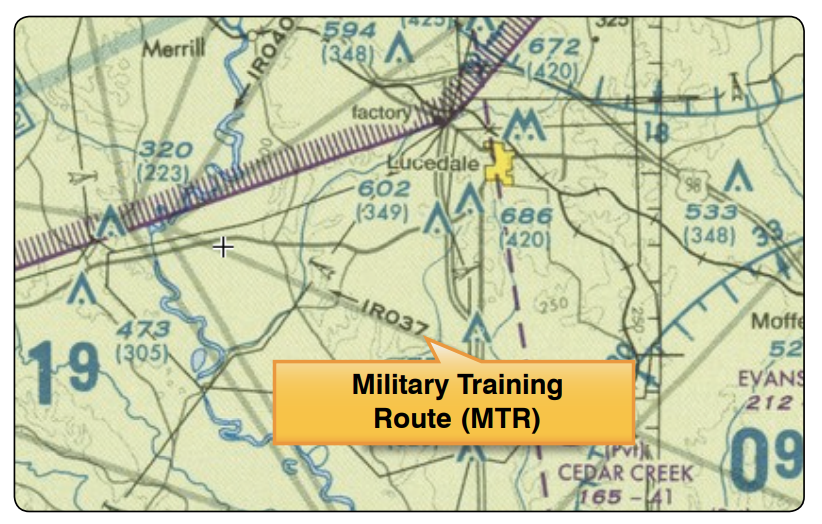

Military Training Routes (MTRs)

MTRs are routes used by military aircraft to maintain proficiency in tactical flying.

These routes are usually established below 10,000 feet MSL for operations at speeds in excess of 250 knots.

Some route segments may be defined at higher altitudes for purposes of route continuity.

Routes are identified as IFR (IR), and VFR (VR), followed by a number.

MTRs with no segment above 1,500 feet AGL are identified by four number characters (e.g., IR1206, VR1207).

MTRs that include one or more segments above 1,500 feet AGL are identified by three number characters (e.g., IR206, VR207).

IFR low altitude en route charts depict all IR routes and all VR routes that accommodate operations above 1,500 feet AGL.

IR routes are conducted in accordance with IFR regardless of weather conditions.

VFR sectional charts depict military training activities, such as IR, VR, MOA, restricted area, warning area, and alert area information.

Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFR)

A flight data center (FDC) Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) is issued to designate a TFR.

The NOTAM begins with the phrase “FLIGHT RESTRICTIONS” followed by the location of the temporary restriction, effective time period, area defined in statute miles, and altitudes affected. The NOTAM also contains the FAA coordination facility and telephone number, the reason for the restriction, and any other information deemed appropriate.

The pilot should check the NOTAMs as part of flight planning.

Some of the purposes for establishing a TFR are:

• Protect persons and property in the air or on the surface from an existing or imminent hazard.

• Provide a safe environment for the operation of disaster relief aircraft.

• Prevent an unsafe congestion of sightseeing aircraft above an incident or event, that may generate a high degree of public interest.

• Protect declared national disasters for humanitarian reasons in the State of Hawaii.

• Protect the President, Vice President, or other public figures.

• Provide a safe environment for space agency operations.

Since the events of September 11, 2001, the use of TFRs has become much more common.

There have been a number of incidents of aircraft incursions into TFRs that have resulted in pilots undergoing security investigations and certificate suspensions.

It is a pilot’s responsibility to be aware of TFRs in their proposed area of flight.

One way to check is to visit the FAA website, and verify that there is not a TFR in the area.

Parachute Jump Aircraft Operations

Published in the Chart Supplement U.S. (formerly Airport/Facility Directory). Sites that are used frequently are depicted on sectional charts.

Published VFR Routes

For transitioning around, under, or through some complex airspace.

Terms such as VFR flyway, VFR corridor, Class B airspace VFR transition route, and terminal area VFR route have been applied to such routes.

These routes are generally found on VFR terminal area planning charts.

Terminal Radar Service Areas (TRSAs)

TRSAs are areas where participating pilots can receive additional radar services.

The purpose of the service is to provide separation between all IFR operations and participating VFR aircraft.

The primary airport(s) within the TRSA become(s) Class D airspace.

The remaining portion of the TRSA overlies other controlled airspace, which is normally Class E airspace beginning at 700 or 1,200 feet and established to transition to/ from the en route/terminal environment.

TRSAs are depicted on VFR sectional charts and terminal area charts with a solid black line and altitudes for each segment.

The Class D portion is charted with a blue segmented line.

Participation in TRSA services is voluntary; however, pilots operating under VFR are encouraged to contact the radar approach control and take advantage of TRSA service.

National Security Areas (NSAs)

NSAs consist of airspace of defined vertical and lateral dimensions established at locations where there is a requirement for increased security and safety of ground facilities.

Flight in NSAs may be temporarily prohibited by regulation under the provisions of 14 CFR Part 99, and prohibitions are disseminated via NOTAM.

Pilots are requested to voluntarily avoid flying through these depicted areas.

It is worth noting that the Armed Forces follow Title 10 of the US Code, and military UAS integration occurs with other government departments.

Informed by the FAA’s draft vision document, Charting Aviation’s Future: Operations in an Info-Centric NAS

Describes future operations in the NAS, with initial capabilities expected to be operational by approximately 2035

Provides a high level description of the integrated future environment

Level 1 concept for the enterprise in accordance with the FAA’s Operational Concept Hierarchy

Broad in scope and describes NAS operations in general terms, serving as the frame of reference for lower-level concepts

Airport Data & Information Portal (ADIP)

The Airport Data and Information Portal (ADIP) helps the FAA collect airport and aeronautical data to meet the demands of the Next Generation National Airspace System.

Guided by Advisory Circulars (ACs), the Airport Sponsor or proponents are key links in the information chain.

Use the Airport Data and Information Portal to access airport data and submit changes matching defined business rules.

FAA lines of business are notified once data has been submitted and approved.

Federal v. State v. Local Powers (Federal and State Preemption)

State sovereignty has been a major issue in American political history.

The founders of the republic designed a federal system that established supremacy for the US government within the realm of its delegated authority while also protecting the sovereign interests of the states.

Certain powers are given to the federal government through the Constitution, and all other matters are reserved to the states through the Tenth Amendment.

This means that each state government is also a sovereign entity.

We therefore have two levels of sovereignty: the federal government and the state governments.

The US Constitution Article VI declares that federal law is the “Supreme Law of the Land.”

As a result, when a federal law conflicts with a state or local law, the federal law will supersede the other laws. This is commonly known as “preemption.”

Congress has vested the FAA with authority to regulate the areas of airspace use, management and efficiency, air traffic control, safety, navigational facilities, and aircraft noise at its source. 49 USC §§ 40103, 44502, and 44701-44735.

Congress has directed the FAA to “develop plans and policy for the use of the navigable airspace and assign by regulation or order the use of the airspace necessary to ensure the safety of aircraft and the efficient use of airspace.” 49 USC § 40103(b)(1).

Congress has further directed the FAA to “prescribe air traffic regulations on the flight of aircraft (including regulations on safe altitudes)” for navigating, protecting, and identifying aircraft; protecting individuals and property on the ground; using the navigable airspace efficiently; and preventing collision between aircraft, between aircraft and land or water vehicles, and between aircraft and airborne objects. 49 USC § 40103(b)(2).

A consistent regulatory system for aircraft and use of airspace has the broader effect of ensuring the highest level of safety for all aviation operations.

To ensure the maintenance of a safe and sound air transportation system and of navigable airspace free from inconsistent restrictions, FAA has regulatory authority over matters pertaining to aviation safety.

In 2015, to address the potential clash between federal and state and local laws, the FAA published a State and Local Regulation of UAS Fact Sheet, which has since been updated… please keep reading!

In this fact sheet the FAA was clear:

UAS are aircraft subject to regulation by the FAA to ensure safety of flight, and safety of people and property on the ground. States and local jurisdictions are increasingly exploring regulation of UAS or proceeding to enact legislation relating to UAS operations. In 2015, approximately 45 states have considered restrictions on UAS. In addition, public comments on the FAA’s proposed rule, “Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems” (Docket No. FAA-2015-0150), expressed concern about the possible impact of state and local laws on UAS operations. Incidents involving unauthorized and unsafe use of small, remote-controlled aircraft have risen dramatically. Pilot reports of interactions with suspected unmanned aircraft have increased from 238 sightings in all of 2014 to 780 through August of this year [2015]. During this past summer, the presence of multiple UAS in the vicinity of wildfires in the western US prompted firefighters to ground their aircraft on several occasions. This fact sheet is intended to provide basic information about the federal regulatory framework for use by states and localities when considering laws affecting UAS. State and local restrictions affecting UAS operations should be consistent with the extensive federal statutory and regulatory framework pertaining to control of the airspace, flight management and efficiency, air traffic control, aviation safety, navigational facilities, and the regulation of aircraft noise at its source.

In 2018 the FAA again reiterated the need for states to avoid stepping on federal toes.

Congress has provided the FAA with exclusive authority to regulate aviation safety, the efficiency of the navigable airspace, and air traffic control, among other things. State and local governments are not permitted to regulate any type of aircraft operations, such as flight paths or altitudes, or the navigable airspace. However, these powers are not the same as regulation of aircraft landing sites, which involves local control of land and zoning. Laws traditionally related to state and local police power – including land use, zoning, privacy, and law enforcement operations – generally are not subject to federal regulation. Cities and municipalities are not permitted to have their own rules or regulations governing the operation of aircraft. However, as indicated, they may generally determine the location of aircraft landing sites through their land use powers.

In 2023, the FAA released an Updated Fact Sheet (2023) on State and Local Regulation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) issued by the FAA, Office of the Chief Counsel, and the United States Department of Transportation, Office of the General Counsel, discussing legal considerations applicable to state and local regulation of UAS.

Like its 2015 predecessor, the Fact Sheet is a guide for state and local governments as they respond to the increased use of UAS in the national airspace.

The 2023 Fact Sheet:

- summarizes well-established legal principles regarding federal authority for regulating the efficiency of the airspace, including the operation or flight of aircraft, which includes, as a matter of law, UAS

- reviews the federal responsibility for ensuring the safety of flight, as well as the safety of people and property on the ground as a result of the operation of aircraft

- sets forth the basic preemption framework applicable to UAS:

-

- States and local governments may not regulate in the fields of aviation safety or airspace efficiency but generally may regulate outside those fields

- A state or local law will be preempted if it conflicts with FAA regulations

- State or local laws affecting commercial UAS operators are more likely to be preempted

As substantial air safety issues are implicated when state or local governments attempt to regulate the operation of aircraft in the national airspace, but legitimate state and local interests in health and safety exist in other contexts, the updated Fact Sheet provides examples of laws addressing UAS that would be subject to federal preemption and others that would likely pass muster.

The updated Fact Sheet concludes with a discussion of Enforcement Matters and Contact Information for Questions.

The FAA Office of the Chief Counsel’s Aviation Litigation Division is available to answer questions about the principles set forth in this fact sheet and to discuss with you the intersection of Federal, state, and local regulation of aviation, generally, and UAS operations, specifically.

State Preemption

Rulemaking Procedure (or how CFRs are born!)

Agencies, like the FAA, get their authority to issue regulations, CFRs, from laws, statutes, enacted by Congress.

Congress may also pass a law that more specifically directs an agency to solve a particular problem or accomplish a certain goal.

An agency must not take action that goes beyond its statutory authority or violates the Constitution.

Agencies must follow an open public process when they issue regulations, according to the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).

This includes publishing a statement of rulemaking authority in the Federal Register (government website) for all proposed and final rules.

The guiding document to the rulemaking process discusses the Petition for Rulemaking, NPRM, Federal Register, Comment Period, interim rule, direct final rule, and effective date, among others.

In a nutshell, Congress mandates the FAA to create CFRs, or the FAA receives a “Petition for Rulemaking” from a member of the public.

The NPRM, drafted by the FAA is then placed on the Federal Register to notify the public and to give them an opportunity to submit comments.

The proposed rule and the public comments received on it form the basis of the final rule.

In general, the FAA will specify a comment period ranging from 30 to 60 days.

For complex rulemakings, the FAA may provide for longer time periods, like 180 days or more.

But they may also use shorter comment periods when that can be justified.

At the end of the comment period, several committees review the comments, and then a final rule is issued.

Final rules have preambles (which provide aviation attorneys like myself insight into the FAA’s thinking).

They are placed on the Federal Register together with a summary and an effective date.

Generally, the rule is effective no less than 30 days after the date of publication in the Federal Register.

If the agency wants to make the rule effective sooner, it must cite “good cause” (persuasive reasons) as to why this is in the public interest.

FAADroneZone Portal

The FAADroneZone is the FAA’s official website for managing your drones whether you fly for recreation, education, government, or business. You use this to register, apply for waivers and airspace authorizations, get recognized as a community-based organization, submit an accident report, among other things.

The FAA recognizes 4 kinds of drone flyer

The FAA recognizes 4 kinds of drone flyer:

(1) Recreational

The law requires that all recreational flyers pass an aeronautical knowledge and safety test and provide proof of passage if asked by law enforcement or FAA personnel. The Recreational UAS Safety Test, TRUST, was developed to meet this requirement.

(2) Educational

(3) Government and Public Safety

This includes Federal, State, Tribal, and Territorial Agencies, law enforcement, and public safety entities. These are defined in AC 00-1.1B – Public Aircraft Operations – Manned and Unmanned.

(4) Commercial

With respect to drone operator documents, drone operators flying in the NAS are required to show certain documents to law enforcement, the NTSB, the TSA, and the FAA upon request. The rules governing the particular flight and the official making the request determine what documents a drone pilot must present.

A recreational flyer operating in accordance with 49 USC § 44809 is required to show their drone registration and proof of TRUST completion to law enforcement upon request. These requirements are listed in 49 USC § 44809 paragraphs (a)(7) and (a)(8). They are not required to show photo identification or airspace authorization to law enforcement.

A remote pilot operating in accordance with 14 CFR part 107 must provide their remote pilot certificate, drone registration, and photo identification upon request from law enforcement. These requirements are listed in 14 CFR §107.7.

2012 – FAA Modernization and Reform Act (FMRA)

2012 – Congress passed the FAA Modernization and Reform Act (FMRA) of 2012, PL 112-95. Section 333 of PL 112-95 directed the Secretary of Transportation to determine whether UAS operations posing the least amount of public risk and no threat to national security could safely be operated in the NAS and, if so, to establish requirements for the safe operation of these systems in the NAS.

2016 – FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act (FESSA)

2016 – Congress enacted the FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act (FESSA) which amended the definition of an SUAS and provided for numerous security, R&D, and usage provisions. It also introduced the concept of remotely identifying operators of UA, as well as gave birth to what we now know as the Special Governmental Interest (SGI) process for expediting approvals for emergency response operations.

2016 – 14 CFR Part 107 – Commercial Drone Rules

2016 – As part of its ongoing efforts to integrate UAS operations in the NAS and in accordance with Section 333, the FAA issued a final rule adding part 107, integrating civil small UAS into the NAS. Part 107 allows small UAS operations for many different purposes without requiring airworthiness certification, exemption, or a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA).

The FAA publishes the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) to make readily available to the aviation community the regulatory requirements placed upon them.

14 CFR Part 107 – Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS)

If you have a small drone that is less than 55 pounds, you can fly for work or business by following the Part 107 guidelines.

First use the FAA user identification tool

Some operations will require a waiver

You can become an FAA-Certified Drone Pilot by Passing the Knowledge Test

To be eligible to get your Remote Pilot Certificate, you must be:

- At least 16 years old

- Able to read, write, speak, and understand English

- Be in a physical and mental condition to safely fly a UAS

Review Knowledge Test Suggested Study Materials provided by the FAA

Create an Integrated Airman Certification and Rating Application (IACRA) profile prior to registering for the knowledge test

Take the Knowledge Test at an FAA-approved Knowledge Testing Center

Once you’ve passed your test, for a remote pilot certificate (FAA Airman Certificate and/or Rating Application) login the FAA Integrated Airman Certificate and/or Rating Application system (IACRA) to complete FAA form 8710-13

Review the full process to get your Remote Pilot Certificate

Register your Drone with the FAA

You should become familiar with:

Title 14 – Aeronautics and Space

BVLOS – Obstruction Shielding Waivers

SGI – Special Government interest Waivers

2024 – Parachute-Equipped Drones Can Fly Over Crowds

The following is a list of the 6 categories of airspace access approval and the process used in the approval of that access.

- Section 44809 – which addresses operations by recreational operators. Operations in the NAS are restricted to at or below 400 ft AGL in Class G airspace and controlled airspace based on pre-coordinated approval through the FAA LAANC Smart Application program.

- 14 CFR Part 107 – for civil and commercial operations not allowed under the 14 CFR Part 107 rule or LAANC Smart Application for controlled airspace, applicant applies in the FAA Drone Zone web Portal for specific airspace authorization.

- 44807 Exemption – Exemption holder received generic blanket COA for operations in class G at or below 400 ft AGL. For operations not covered under the blanket Class G COA, applicant applies for COA within the COA Online Application Processing System (CAPS) Online Portal.

- Experimental Category – The COA in support of the Operating Limitations document issued by the CMS, is issued through coordination with the FAA Air Traffic Policy office who coordinates with the 3 Air Traffic Operational Support Group Service Centers for the processing of the COA.

- Public Aircraft Operations – the Public Agency applies for the approved COA within the COA Online Application Processing system (CAPS) online portal.

- Type Certificated Aircraft – The applicant applies for the approved COA within the COA Online Application Processing system (CAPS) online portal.

AC 107-2A – Small UAS

The FAA issues Advisory Circulars (AC) to inform the aviation public in a systematic way of nonregulatory material.

Unless incorporated into a regulation by reference, the contents of an AC are not binding on the public. ACs are not mandatory and do not constitute a regulation. The contents do not have the force and effect of law and are not meant to bind the public in any way, and the document is intended only to provide clarity to the public regarding existing requirements under the law or agency policies.

Advisory Circulars are issued in a numbered subject system corresponding to the subject areas of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).

AC 107-2A – Small UAS

FAA UAS Waiver Process

Learn how the FAA processes UAS requests with JO 7200.23D – Processing of Unmanned Aircraft Systems Requests.

This order provides guidance for Headquarters, Service Centers, and Air Traffic Managers on air traffic policies and prescribes procedures for the planning, coordination, and services involving the processing of applications for the operation of UAS in the NAS.

Unless otherwise indicated in this order, all applications are processed at the Service Centers.

However, in the case of certain high priority applications, the Headquarters may choose to process the application.

This order establishes air traffic policy for the processing of authorization and waiver requests for UAS operations in the NAS.

An unmanned aircraft system that is operated underground for mining purposes must not be subject to regulation or enforcement by the FAA under title 49, United States Code, Section 355.

2018 – FAA Reauthorization Act

2018 – The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 repealed the Special Rule for Model Aircraft of FMRA 2012 and replaced it with the Exception for limited recreational operations; and also repealed Section 333 of FMRA 2012 and replaced it with a risk-based approach under Section 44807. However, those rules under Part 107 did not permit SUA operations at night or over people without a waiver. Section 2209 of FESSA was again mentioned in this act.

In the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018, Congress addressed privacy and UAS.

SEC. 357. UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEMS PRIVACY POLICY.

SEC. 358. UAS PRIVACY REVIEW.

SEC. 375. FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION AUTHORITY.

SEC. 378. SENSE OF CONGRESS.

In the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018, Congress addressed UAS crimes.

SEC. 381. UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEMS IN RESTRICTED BUILDINGS OR GROUNDS.

SEC. 382. PROHIBITION.

SEC. 384. UNSAFE OPERATION OF UNMANNED AIRCRAFT.

49 USC 44809 – Recreational Drone Rules

The rule for operating UAS under 55 pounds in the NAS is 14 CFR 107.

However, if you want to fly your UAS for purely recreational purposes, there is a limited statutory exception (“carve out”) that provides a basic set of requirements.

A recreational flight is one that is not operated for a business or any form of compensation.

However, financial compensation, or the lack of it, is not what determines if the flight is recreational or commercial.

Non-recreational purposes include things like taking photos to help sell a property or service, roof inspections, or taking pictures of a high school football game for the school’s website.

Goodwill or other non-monetary value can also be considered indirect compensation.

This would include things like volunteering to use your UAS to survey coastlines on behalf of a non-profit organization.

Recreational flight is simply flying for fun or personal enjoyment.

The Exception for Limited Operation of Unmanned Aircraft (49 USC 44809) or “carve out” is the law that describes how, when, and where you can fly UAS for recreational purposes.

Following these rules will keep people, your drone, and the NAS safe:

- Fly only for recreational purposes (personal enjoyment).

- Follow the safety guidelines of an FAA-recognized Community Based Organization (CBO). Read AC 91-57C.

- Keep your drone within your visual line of sight or use a VO who is co-located (physically next to) and in direct communication with you.

- Give way to and do not interfere with manned aircraft.

- Fly at or below 400 feet in controlled airspace (Class B, C, D, and surface E designated for an airport) only with prior authorization by using LAANC or FAADroneZone.

- Fly at or below 400 feet in Class G (uncontrolled) airspace.

- Take The Recreational UAS Safety Test (TRUST) and carry proof of test passage.

- Have a current registration, mark your drones on the outside with the registration number, and carry proof of registration with you. If your drone requires an FAA registration number it will be also required to broadcast Remote ID information.

- Do not operate your drone in a dangerous manner.

- Do not interfere with emergency response or law enforcement activities.

- Do not fly under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

Individuals violating any of these rules, and/or operating in a dangerous manner, may be subject to FAA enforcement action.

As of February 20, 2023, Recreational Flyers may request an airspace authorization to operate in controlled airspace at night through LAANC.

As a recreational flyer you can fly in controlled airspace if you have an airspace authorization from the FAA prior to flight through LAANC or the FAA’s Drone Zone.

In LAANC enabled areas authorizations are provided to drone pilots through companies approved by the FAA.

These companies are known as FAA-Approved UAS Service Suppliers (FAA LAANC USSs).

The companies have built desktop and mobile applications through which drone pilots submit their authorization request and receive other safety critical information related to their flight.

The companies provide near-real time airspace authorizations at pre-approved altitudes on the UAS Facility Maps.

All companies provide information about the maximum altitude you can fly in a specific location and whether or not your flight is in controlled or uncontrolled airspace.

Follow these steps to get approval to fly through LAANC:

– Register your drone

– Take The Recreational UAS Safety Test (TRUST).

– Apply on the date you wish to fly (requests may be submitted up to 90 days in advance of your planned flight).

– Select the exact time, altitude and location where you wish to fly. Make sure you select to fly at or below the altitude defined by the UAS Facility Maps (this will show up automatically in your LAANC provide app).

FAA Drone Zone provides authorizations for airports that are not LAANC-enabled, however it does not provide authorizations in near-real time.

All requests are processed manually at the FAA Air Traffic Service Centers.

Only apply for authorization at or below approved altitudes on the UAS Facility Maps.

Airspace Authorization through FAA Drone Zone:

– Log into the FAA Drone Zone under The Exception for Recreational Flyers

– Select “Airspace Authorization”.

– Fill in the required fields – Review and submit your information to the FAA.

– Upon submission you will receive a reference number for your application.

– You may check you application status anytime by logging back into the FAA DroneZone.

– If you have questions while filling out the request, contact the UAS Support Center.

On August 7, 2023, the FAA released Agency Information Collection Activities: Requests for Comments; Clearance of Continued Approval of Information Collection: Limited Recreational Unmanned Aircraft Operation Applications – Comments closed 10-6-2023

AC 91-57C – Exception for Limited Recreational Operations of UA

The FAA issues Advisory Circulars (AC) to inform the aviation public in a systematic way of nonregulatory material.

Unless incorporated into a regulation by reference, the contents of an AC are not binding on the public. ACs are not mandatory and do not constitute a regulation. The contents do not have the force and effect of law and are not meant to bind the public in any way, and the document is intended only to provide clarity to the public regarding existing requirements under the law or agency policies.

Advisory Circulars are issued in a numbered subject system corresponding to the subject areas of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).

AC 91-57C – Exception for Limited Recreational Operations of Unmanned Aircraft

Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) Waiver

Flying Sites in Class G Airspace Granted Higher Altitudes

AMA has been granted a National Authorization allowing their members at AMA club sites in Class G airspace to operate above 400 feet above ground level (AGL) for routine, day-to-day activities.

Based on their location in Class G airspace, their site has a new altitude limit of up to 700 feet or 1,200 feet AGL.

Know Before You Fly