2 Canada

Two vertical bands of red (hoist and fly side, half width) with white square between them. An 11-pointed red maple leaf is centered in the white square. The maple leaf has long been a Canadian symbol.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of CIA World Factbook

An “Old World” floor mosaic of Europe in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, Canada is a constitutional monarchy. The titular head is the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom (locally called the king or queen of Canada), who is represented locally by a governor-general (now always Canadian and appointed by the Canadian prime minister). In practice, however, Canada is an independent federal state established in 1867 by the British North America Act. The act created a self-governing British dominion (recognized as independent within the British Empire by Britain in 1931) and united the colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Canada into the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, and Ontario. Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territories were acquired from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869, and from them Manitoba was created and admitted to the confederation as a province in 1870; its extent was enlarged by adding more areas from the territories in 1881 and 1912. The colonies of British Columbia and Prince Edward Island were admitted as provinces in 1871 and 1873, respectively. In 1905, Saskatchewan and Alberta were created from what remained of the Northwest Territories and admitted to the confederation as provinces. In 1912, the provinces of Quebec and Ontario were enlarged by adding areas from the Northwest Territories. In 1949, Newfoundland and its mainland dependency, Labrador, joined the confederation following a popular referendum (the province was officially renamed Newfoundland and Labrador in 2001). The Yukon Territory (renamed Yukon in 2003) was separated from the Northwest Territories in 1898, and Nunavut was created from the eastern part of the territories in 1999. Thus, Canada now consists of 10 provinces and 3 territories, which vary greatly in size.

All vestiges of British control ended in 1982, when the British Parliament passed the Canada Act, which formally made Canada responsible for all changes to its own constitution. The Canada Act (also known as the Constitution Act) is not an exhaustive statement of the laws and rules by which Canada is governed. Broadly speaking, the Canadian constitution includes other statutes of the United Kingdom; statutes of the Parliament of Canada relating to such matters as the succession to the throne, the demise of the crown (i.e., death of the monarch), the governor-general, the Senate, the House of Commons, electoral districts, elections, and royal style and titles; and statutes of provincial legislatures relating to provincial legislative assemblies. Many of the rules and procedures of Parliament are not laid down in the Constitution Act but are established by (often British) convention and precedent.

The Official Languages Act of 1969 declares that the English and French languages “enjoy equality of status and equal rights and privileges as to their use in all the institutions of the Parliament and Government of Canada.”

Federal legislative authority is vested in the Parliament of Canada, which consists of the sovereign (governor-general), the House of Commons, and the Senate. Both the House of Commons, which has 338 directly elected members, and the Senate, which normally consists of 105 appointed members, must pass all legislative bills before they can receive royal assent and become law. Both bodies may originate legislation, but only the House of Commons may introduce bills for the expenditure of public funds or the imposition of any tax. The House of Commons is more powerful than the Senate, whose chief functions include investigation, reviewing government legislation, and debating key national and regional issues.

The governor-general, who holds what is now a largely ceremonial position, is appointed by the reigning monarch of the Commonwealth upon the advice of the Canadian government. The governor-general formally summons, prorogues, and dissolves Parliament, assents to bills, and exercises other executive functions. After a general election, the governor-general calls on the leader of the party winning the most seats in the House of Commons to become prime minister and to form a government. The prime minister then chooses a cabinet, generally drawn from among the members of the House of Commons from that same party. Almost all cabinet ministers head executive departments, and the cabinet, led by the prime minister, develops all policies and secures passage of legislation.

The ministers of the crown, as members of the cabinet are called, are chosen generally to represent all regions of the country and its principal cultural, religious, and social interests. Although they exercise executive power, cabinet members are collectively responsible to the House of Commons and remain in office only so long as they retain its confidence. The choice of the Canadian electorate not only determines who shall govern Canada but also, by deciding which party receives the second largest number of seats in the House, designates which of the major parties becomes the official opposition. The function of the opposition is to offer intelligent and constructive criticism of the existing government.

The Canada Act divides legislative and executive authority between the federal government and the provinces. Among the main responsibilities of the national government are defense, trade and commerce, banking, credit, currency and bankruptcy, criminal law, citizenship, taxation, postal services, fisheries, transportation, and telecommunications. In addition, the federal government is endowed with a residual authority in matters beyond those specifically assigned to the provincial legislatures, including the power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of Canada.

Provincial political institutions and constitutional usages mirror those operating at the federal level. In each province the sovereign is represented by a lieutenant governor appointed by the governor-general in council, usually for a term of five years. The provincial lieutenant governor exercises powers similar to those of the federal governor-general.

Each province holds elections for a single-chamber legislative assembly, from which a premier and cabinet are selected; legislators serve for five-year terms. The provinces have powers embracing mainly matters of local or private concern such as property and civil rights, education, civil law, provincial company charters, municipal government, hospitals, licenses, management and sale of public lands, and direct taxation within the province for provincial purposes. The vast and sparsely populated regions of northern Canada lying outside the 10 provinces, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut, are administered by the federal government, but they elect members to the House of Commons and enjoy local self-government.

A major part of Canada’s constitutional development has occurred gradually through judicial interpretation and constitutional convention and through executive and administrative coordination at the federal and provincial levels of government. Through such devices, the national and provincial legislatures have been able to retain their separate jurisdictions over different aspects of the same matters. Regular meetings of provincial premiers and the federal prime minister are held to discuss federal-provincial jurisdictional issues, generally ensuring an accommodation that gives fair assurances to the aspirations of the provinces without disrupting the integrated national structure of Canada.

Because municipal government falls under the jurisdiction of the provinces, there are 10 distinct systems of municipal government in Canada, as well as many variations within each system. The variations are attributable to differences in historical development and in area and population density. Thus, the legislature of each province has divided its territory into geographic areas known generally as municipalities and, more particularly, as counties, cities, towns, villages, townships, rural municipalities, or municipal districts.

The county system as understood in Britain or the United States exists only in southern Ontario and southern Quebec. County councils are composed of representatives from rural townships, towns, and villages and provide a second level of services for the whole county. This two-tiered municipal government was first extended to urban areas when Metropolitan Toronto was established in 1953. A number of other highly urbanized areas in Ontario have since adopted a metropolitan or regional form of government to deal with common areawide problems. More recently, cities such as Toronto have been further amalgamated with their surrounding districts; at the same time, the number of representative councillors has been reduced.

The more than 4,500 incorporated municipalities and local government districts in Canada have various powers and responsibilities suited to their classification. A municipality is governed by an elected council. The responsibilities of the municipalities are generally those most closely associated with the citizens’ everyday life, well-being, and protection. In addition to local municipal government, there are numerous local boards and commissions, some elected and others appointed, to administer education, utilities, libraries, and other local services.

The sparsely populated areas of the provinces are usually administered as territories by the provincial governments. Aboriginal self-government became an increasingly important issue during the last two decades of the 20th century.

Canadian courts of law are independent bodies. Each province has its police, division, county, and superior courts, with the right of appeal being available throughout provincial courts and to the federal Supreme Court of Canada. At the federal level, the Federal Court has civil and criminal jurisdictions with appeal and trial divisions. All judges, except police magistrates and judges of the courts of probate in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, are appointed by the governor-general in council, and their salaries, allowances, and pensions are fixed and paid by the federal Parliament. Judges serve in office until age 75, at which time they are required to retire. Criminal law legislation and procedure in criminal matters is under the jurisdiction of the Parliament of Canada. The provinces administer justice within their boundaries, including organizing civil and criminal codes and establishing civil procedure. Since 1982, when the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was incorporated into the constitution, the interpretative role of the Supreme Court has increased significantly.

Transport Canada

Transport Canada is the department within the Government of Canada responsible for developing regulations, policies and services of road, rail, marine and air transportation in Canada. It is part of the Transportation, Infrastructure and Communities portfolio.

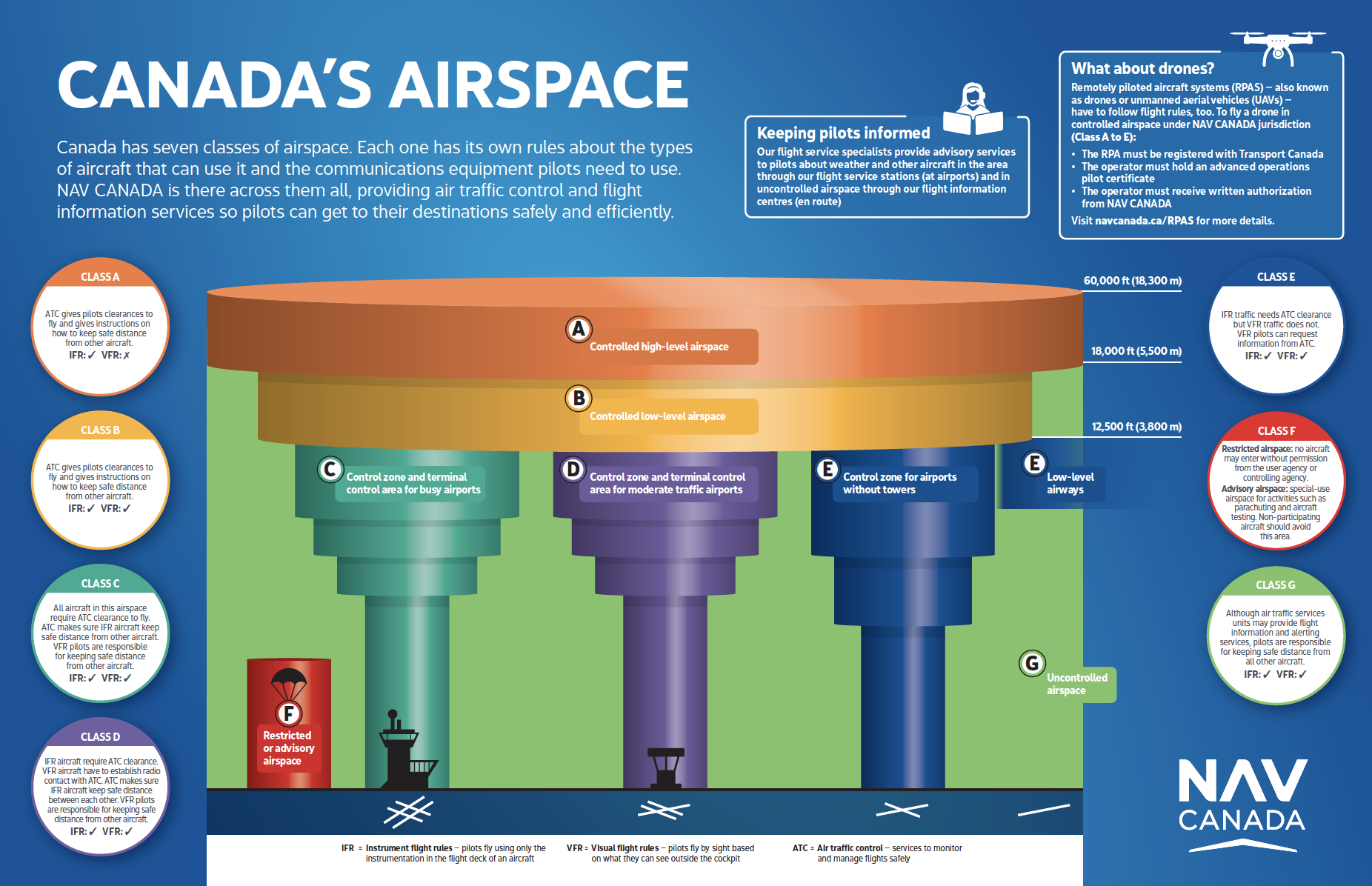

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

Nav Canada

ATC is handled by NAV CANADA

NAV CANADA manages 18 million square kilometres of Canadian and oceanic airspace. Their air traffic controllers direct planes, either from the cab of a control tower or on a radar screen in an area control center (ACC), 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. They work with pilots operating all types of planes, from single-engine aircraft to large multi-engine jets. Air traffic controllers ensure aircraft maintain vertical, lateral or time separation, while following strictly defined rules, procedures, and regulations.

Designated Airspace Handbook and other great resources.

Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM) – TP 14371 provides flight crews with a single source for information on rules and procedures for aircraft operation in Canadian airspace. It has been developed to bring together pre-flight reference information of a lasting nature into a single primary document. Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) details may be found on pages 431 to 458.

Drone Regulations

Drone Regulations may be found on Transport Canada website.

2025 Summary of changes to Canada’s drone regulations

Transport Canada’s Drone Strategy to 2025

Transport Canada’s Drone Strategy to 2025

CARs – Part IX – RPAS

Drone pilots must respect all other laws, such as:

Relevant sections of the Criminal code:

Offenses against Air or Maritime Safety

Trespass act of the province

Laws relating to voyeurism and privacy

It’s worth reading this excellent briefing on privacy for drone pilots.

Transport Canada will fine individuals and corporations for breaking these rules.

Drone Innovation and Collaboration

Provinces and Territories of Canada

Newfoundland and Labrador – NF and LB

Prince Edward Island – PEI

Quebec – PQ

Saskatchewan – SK

C-UAS

Counter Uncrewed Aerial Ssystems Concept Development

Counter Uncrewed Aerial Systems Sandbox 2024

Applicable laws include:

Radiocommunication Act – Sections 4(4) and 9(1)(b)

Radiocommunication Act Exemption Order [Jammers – Royal Canadian Mounted Police]

Criminal Code – Sections 342.1 and 342.2

Case study of drone collision in Canada – Aug. 10, 2021 – Cessna 172 and a 15-pound DJI Matrice M210

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

Canadian Advanced Air Mobility Consortium

Update on AAM implementation in Canada

2024 – Transport Canada Drone Infrastructure Testing Goes to Phase 2

Bilateral agreements facilitate the reciprocal airworthiness certification of civil aeronautical products imported/exported between two signatory countries. A Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement (BAA) or Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement (BASA) with Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA) provides for airworthiness technical cooperation between the FAA and its counterpart civil aviation authorities.

Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement – Executive Agreement

Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (Revision 3)

FAA-TCCA Bilateral Enhancement Roadmap, Issue 1

2016 Notification of Policy Deviation Memorandum for FAA Order 8130.21H

Flight Standards Agreements

Implementation Procedures for Licensing (IPL), Revision 1

Simulator Implementation Procedures (SIP)

Maintenance Implementation Procedures (MIP)

Obtaining Certification Approval from this Country

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

2025 – Canadian AAM group welcomes new national board members

2025 – Volatus Aerospace gains approval for BVLOS drone flights at night

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 3 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

2024 – CORRIDAIR Project: Awarded $2 Million from Quebec for Sustainable Air Mobility

2024 – Collaboration to Increase Autonomy in Advanced Air Mobility Solutions in Quebec

2023 – Limosa partners with BAC Aerospace to begin historic Canadian eVTOL certification process

2023 – Jaunt’s Cote joins board of Aero Montreal to help build Quebec as AAM center

2022 – VPorts creates electric AAM corridors between Quebec and U.S.

2022 – CAAM and CARTAMS “to develop five year UAM roadmap for Canada”

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone in the city of Toronto.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in, and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?