110 Spain

Three horizontal bands of red (top), yellow (double width), and red with the national coat of arms on the hoist side of the yellow band. The coat of arms is quartered to display the emblems of the traditional kingdoms of Spain (clockwise from upper left, Castile, Leon, Navarre, and Aragon) while Granada is represented by the stylized pomegranate at the bottom of the shield. The arms are framed by two columns representing the Pillars of Hercules, which are the two promontories (Gibraltar and Ceuta) on either side of the eastern end of the Strait of Gibraltar. The red scroll across the two columns bears the imperial motto of “Plus Ultra” (further beyond) referring to Spanish lands beyond Europe. The triband arrangement with the center stripe twice the width of the outer dates to the 18th century.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

The neo-Gothic facade of the Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Santa Eulalia in Barcelona (built 13th-15th centuries).

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, from 1833 until 1939 Spain almost continually had a parliamentary system with a written constitution. Except during the First Republic (1873–74), the Second Republic (1931–36), and the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), Spain also always had a monarchy. For a complete list of the kings and queens regnant of Spain.

From the end of the Spanish Civil War in April 1939 until November 1975, Spain was ruled by Gen. Francisco Franco. The principles on which his regime was based were embodied in a series of Fundamental Laws (passed between 1942 and 1967) that declared Spain a monarchy and established a legislature known as the Cortes. Yet Franco’s system of government differed radically from Spain’s modern constitutional traditions.

Under Franco the members of the Cortes, the procuradores, were not elected on the democratic principle of one person, one vote but on the basis of what was called “organic democracy.” Rather than representing individual citizens, the procuradores represented what were considered the basic institutions of Spanish society: families, the municipalities, the universities, and professional organizations. Moreover, the government, appointed and dismissed by the head of state alone, was not responsible to the Cortes, which also lacked control of government spending.

In 1969 Franco selected Juan Carlos de Borbón, the grandson of King Alfonso XIII, to succeed him as head of state. When Franco died in 1975, Juan Carlos came to the throne as King Juan Carlos I. Almost immediately the king initiated a process of transition to democracy that within three years replaced the Francoist system with a democratic constitution.

The product of long and intense negotiations among the leading political groups, the Spanish constitution was nearly unanimously approved by both houses of the legislature (it passed 551–11 with 22 abstentions) in October 1978. In a December referendum, the draft constitution was then approved by nearly 90 percent of voters. The constitution declares that Spain is a constitutional monarchy and advocates the essential values of freedom, justice, equality, and political pluralism. It also provides for the separation of powers into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Although the monarch is the head of state and the country’s highest representative in international affairs, the crown’s role is defined as strictly neutral and apolitical. The monarch is also commander in chief of the armed forces, though without actual authority over them, and the symbol of national unity. For example, when the new democratic constitution was threatened by a military coup in 1981, Juan Carlos in military uniform addressed the country on national television, defusing the uprising and saving the constitution. The monarch’s most important functions include the duty to summon and dissolve the legislature, appoint and accept the resignation of the prime minister and cabinet ministers, ratify laws, declare wars, and sign treaties decided upon by the government.

The legislature, known as the Cortes Generales, is composed of two chambers (cámaras): a lower chamber, the Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados), and an upper chamber, the Senate (Senado). As with most legislatures in parliamentary systems, more power is vested in the lower chamber. The Congress of Deputies has 350 members, who are elected to four-year terms by universal suffrage. The Senate is described in the constitution as the “chamber of territorial representation,” but only about one-fifth of the senators are actually chosen as representatives of the autonomous communities. The rest are elected from the 47 mainland provinces (with each province having four senators), the islands (the three largest having four and the smaller ones having one each), and Ceuta and Melilla (having two each).

The executive consists of the prime minister, the deputy prime minister, and the members of the cabinet. After consultation with the Cortes, the monarch formally appoints the prime minister; the cabinet ministers, chosen in turn by the prime minister, are also formally appointed by the monarch. The executive handles domestic and foreign policy, including defense and economic policies. Since the executive is responsible to the legislature and must be approved by a majority vote, the prime minister is usually the leader of the party that has the most deputies. The Congress of Deputies can dismiss a prime minister through a vote of no confidence.

For most of the period after 1800, Spain was a highly centralized state that did not recognize the country’s regional diversity. Decades of civil unrest followed Isabella II’s accession to the throne in 1833, as factions warred over the role of the Roman Catholic Church, the monarchy, and the direction of Spain’s economy. The constitution of the short-lived First Republic called for self-governing provinces that would be voluntarily responsible to the federal government; however, decentralization led to chaos, and by 1875 the constitutional monarchy was restored. For the rest of the 19th century, Spain remained relatively stable, with industrial centers such as the Basque region and Catalonia experiencing significant economic growth while most of the rest of Spain remained poor. Following Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War (1898), many Spaniards viewed their country’s political and economic systems as unworkable and antiquated. Groups in Catalonia, the Basque region, and Galicia who wanted to free their regions from the “Castilian corpse” began movements for regional autonomy, and a number of influential regional political parties consolidated their strength. One of the stated goals of the Second Republic was to grant autonomy to the regions, as it did to Catalonia and the Basque provinces; however, self-government for these regions was not reinstated after the Civil War.

During the Franco years the democratic opposition came to include regional autonomy as one of its basic demands. While the 1978 constitution reflected this stance, it also was the product of compromise with the political right, which preferred that Spain remain a highly centralized state. The result was a unique system of regional autonomy, known as the “state of the autonomies.”

Article 2 of the constitution both recognizes the right of the “regions and nationalities” to autonomy and declares “the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation.” Title VIII states that “Adjoining provinces with common historic, cultural and economic characteristics, the islands and the provinces with a historical regional identity” are permitted to form autonomous communities.

The constitution classifies the possible autonomous communities into two groups, each of which has a different route to recognition and a different level of power and responsibility. The three regions that had voted for a statute of autonomy in the past, Catalonia, the Basque provinces, and Galicia, were designated “historic nationalities” and permitted to attain autonomy through a rapid and simplified process. Catalonia and the Basque Country had their statutes approved in December 1979 and Galicia in April 1981. The other regions were required to take a slower route, although Andalusia was designated as an exception to this general rule. It was not a “historic nationality,” but there was much evidence, including mass demonstrations, of significant popular support for autonomy. As a result, a special, quicker process was created for it.

By May 1983 the entire country had been divided into 17 comunidades autónomas (autonomous communities): the Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia, Andalusia, Asturias, Aragon, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile and León, Castile-La Mancha, Extremadura, Navarra, La Rioja, and the regions of Madrid, Murcia, and Valencia. In 1995 two autonomous cities, Ceuta and Melilla, were added.

The basic political institutions of each community are similar to those of the country as a whole. Each has a unicameral legislature elected by universal adult suffrage and an executive consisting of a president and a Council of Government responsible to that legislature.

The powers (competencias) to be exercised by the regional governments are also stated in the constitution and in the regional statute of autonomy. However, there were differences between the “historic nationalities” and the other communities in the extent of the powers that were initially granted to them. For the first five years of their existence, those communities that had attained autonomy by the slow route could assume only limited responsibilities. Nevertheless, they had control over the organization of institutions, urban planning, public works, housing, environmental protection, cultural affairs, sports and leisure, tourism, health and social welfare, and the cultivation of the regional language (where there was one). After five years these regions could accede to full autonomy, but the meaning of “full autonomy” was not clearly defined. The transfer of powers to the autonomous governments has been determined in an ongoing process of negotiation between the individual communities and the central government that has given rise to repeated disputes. The communities, especially Catalonia and Andalusia, have argued that the central government has dragged its feet in ceding powers and in clarifying financial arrangements. In 2005 the Cortes granted greater autonomy to Catalonia, declaring the region a nation in 2006.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the Spanish state had yet to achieve a form of regional government that was wholly acceptable to all its communities, but, whenever that happens, it will almost inevitably be an asymmetrical form in which the range of powers held by the regional governments will vary widely from one community to another.

There are two further levels of government below the national and regional, provincias and municipios (provinces and municipalities). Their powers and responsibilities are set out in the Basic Law on Local Government (1985).

The provinces, in existence since 1833, originally served as transmission belts for the policies of the central government. Although they still perform this function, the provinces now also bring together and are dependent on the governments of the municipalities.

There are more than 8,000 municipal governments (ayuntamientos). Each has a council, a commission (a kind of cabinet), and a mayor (alcalde). Municipal councillors are elected by universal adult suffrage through a system of proportional representation. As in elections to the national parliament, votes are cast for party lists, not for individual candidates.

Municipal governments may pass specific local regulations so long as they conform to legislation of the national or regional parliament. While municipal governments receive funds from the central government and the regions, they can also levy their own taxes; in contrast, provincial governments cannot.

A provincial council (Diputación Provincial) is responsible for ensuring that municipalities cooperate with one another at the provincial level. The main function of these councils is to provide a range of services not available to the smaller municipalities and to develop a provincewide plan for municipal works and services. There are no provincial councils in the autonomous regions that comprise one province (Asturias, Navarra, La Rioja, Cantabria, Madrid, and Murcia). In the Basque Country, provincial councils are elected directly by universal adult suffrage. The islands, too, choose their corporate body by direct election; each of the seven main Canary Islands and the main Balearic Islands elect island councils (Cabildo Insular and Consell Insular, respectively).

The judicial system, known as the poder judicial, is independent of the legislative and executive branches of government. It is governed by the General Council, which comprises lawyers and judges.

There are a number of different levels and types of courts. At the apex of the system is the Supreme Court, the country’s highest tribunal, which comprises five chambers. The National Court (Audiencia Nacional) has jurisdiction throughout Spain and is composed of three chambers (criminal, administrative, and labour). Each autonomous community has its own high court of justice (Tribunal Superior de Justica), and all the provinces have high courts called the audiencias that try criminal cases. Below these are courts of first instance, courts of judicial proceedings (which do not pass sentences), penal courts, and municipal courts. Created by law in 1981 and reporting to the Cortes, the ombudsman (defensor del pueblo) defends citizens’ rights and monitors the activities of all branches of government.

The Constitutional Court (Tribunal Constitucional), which is not part of the judiciary, is responsible for interpreting the constitution and the constitutionality of laws and for settling disputes between central and regional powers regarding constitutional affairs. The Constitutional Court is composed of 12 members who are formally appointed by the monarch after being elected by three-fifths of both the Congress of Deputies and the Senate (four members each) and by the executive and the General Council (two members each).

Civil / National Aviation Authority (CAA/NAA)

The General Directorate of Civil Aviation is the body that designs the strategy and defines the aviation policy, prepares and proposes regulations and coordinates the agencies, entities and entities attached to the Department with functions in civil aviation. The State Aviation Safety Agency, responsible for ensuring the safety of civil aviation and the protection of user rights, is one of these entities, and works with full functional independence for the best achievement of its goals.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

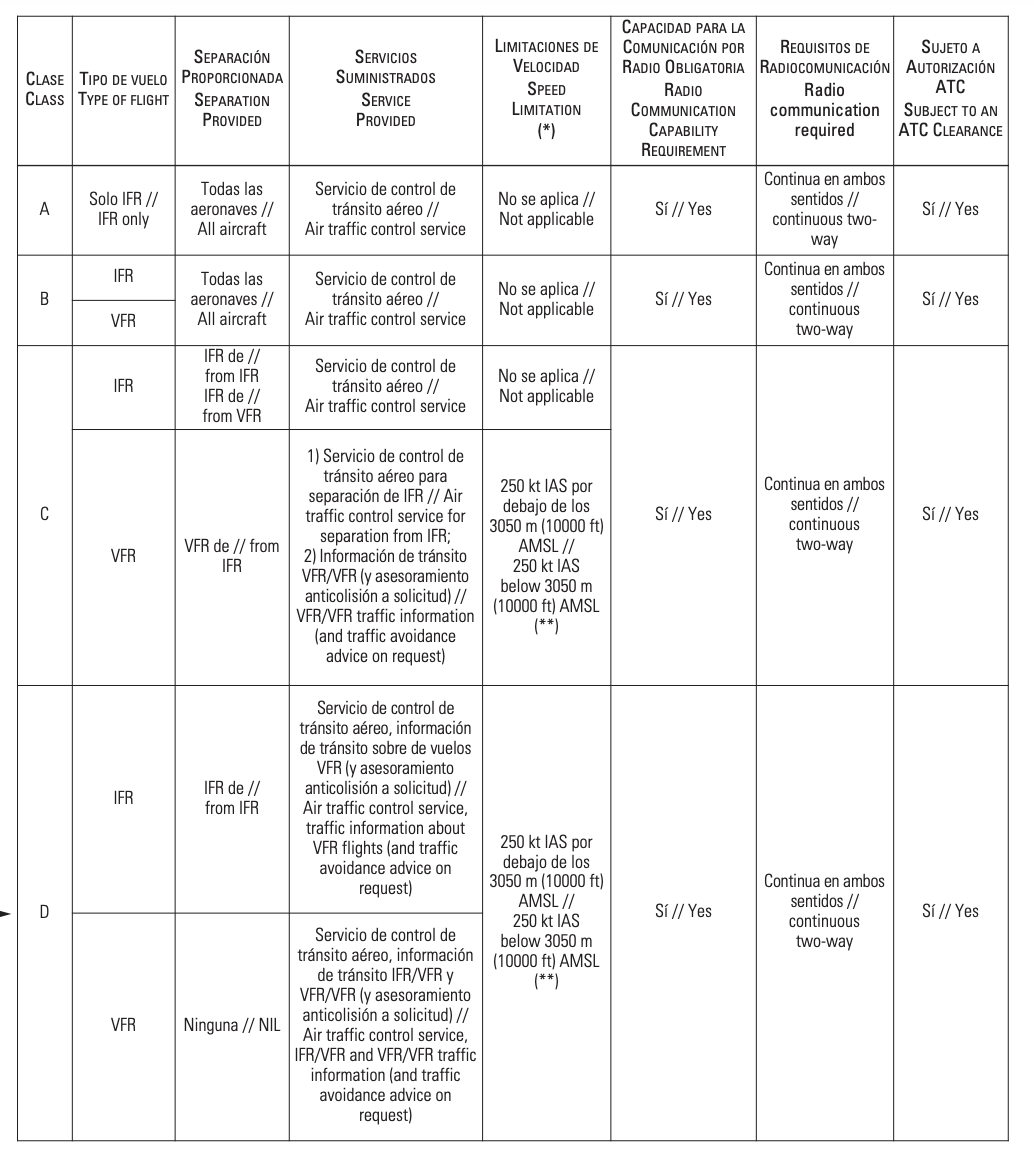

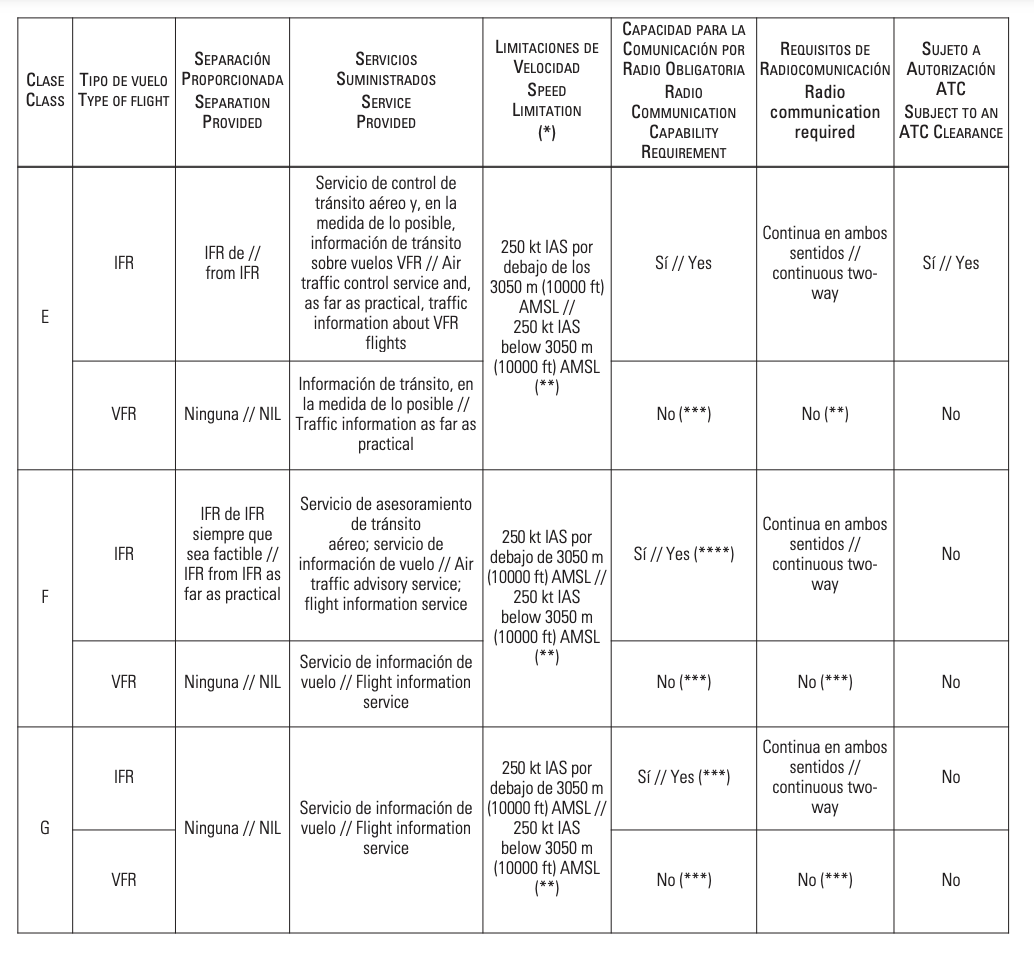

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G. Spain AIP

Map of where you can fly your drone in Spain

ENAIRE – All aircraft that take off from, land in or cross Spain’s airspace receive communication, navigation and surveillance services through a modern and comprehensive network of facilities operated by ENAIRE. Similarly, the aircraft are attended by one or various air traffic control operators (ATCOs) who, depending on the flight phase, provide their services from a specific unit, guaranteeing at all times that aircraft uphold the safety levels which the separations between them determine.

Drone Regulations

Minimum requirements to fly any drone as of December 31, 2020

Since December 31, 2020, the European regulation of UAS (drones) is applicable. This standard affects all drones regardless of their use* (recreational or professional) or size/weight. This section contains the minimum obligations to comply with before flying any drone:

Registration as an operator: All users who intend to fly a drone** must register as operators at the AESA electronic headquarters and obtain the operator number according to European regulations ( UAS operator registration section ). Once the operator number is obtained, it must be included in the drone in a visible way.

Train as a pilot: To fly a drone you must have a minimum of creditable training depending on the operational category in which it is operated. The training and knowledge test to be able to operate a drone in the open category, subcategories A1 and A3, is accessible through the AESA website ( UAS pilot training section ). The training is online and free and after passing the online exam AESA will issue you a certificate.

Availability of mandatory civil liability insurance: an insurance policy must be taken out that covers civil liability against third parties for damages that may arise during and due to the execution of each flight that is carried out, both for recreational and professional purposes. More information on insurance in the section on European regulations for UAS/drones

Flight rules: The drone flight is subject to general operating rules conditioned, among others, by the weight of the drone, the presence of other people and the proximity to buildings. You can consult the different operational categories in the ” UAS/drones operations ” section, where there is also a questionnaire that will help you to know in which operational category the intended flights would fall and instructions to carry them out ( link to the questionnaire ) .

Place of the flight: In addition to the general rules of drone operation, there are limitations on the flight of drones in certain places motivated by different reasons: proximity to aerodromes, military zones, protection of critical infrastructures, environmental protection, etc. Consult the section “ Flight with UAS/drones ” to find out the flight requirements in the different areas of Spain.

*Except non-EASA activities (Fire fighting, search and rescue, police, customs, etc.)

** Except for the exceptions indicated in the ” open category operations ” section or if you have been hired as a remote pilot or you are flying for someone else, in which case the person who must register is the drone operating organization.

New European regulation of Drones

IMPORTANT: As of December 31, 2020, the European UAS regulations apply. This standard affects all drones regardless of their use or size. This section contains the applicable regulations and frequently asked questions about them. You can find more detailed information on specific aspects in the different sections of the website within the “drones field”. A summary with the key aspects and minimum obligations are detailed in the point Do you have a drone? .

Frequently asked questions about European UAS regulations prepared by EASA

Consolidated European regulations:

Consolidated Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947 including changes to Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/639, Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/746, Implementing Regulation 2021/1166 and Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/ 425. ( link to standard ).

Consolidated Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/945 that includes the changes to Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/1058. ( link to standard ).

Easy Access Rules for Unmanned Aircraft Systems (Regulations (EU) 2019/947 and (EU) 2019/945) .

Link to EASA frequently asked questions on European UAS regulations: FAQ UAS EASA

Activities or services not EASA

European regulations are not applicable to “non-EASA activities or services” so operators that carry out this type of activity must comply with the provisions of Royal Decree 1036/2017.

“Non-EASA activities or services” are those excluded from the scope of application of Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 of the European Parliament and of the Council, article 2.3, letter a), carried out by military, customs, police, search and salvage, fire-fighting, border control, coastal surveillance or the like, under the control and responsibility of a Member State, undertaken in the general interest by or on behalf of a body vested with public authority.

Additional information to carry out this type of operation is available in the section “UAS NOT EASA Operators ”.

Availability of compulsory civil liability insurance

After the modification of the Air Navigation Law, and until the entry into force of the UAS Royal Decree * that completes the legal regime for the civil use of unmanned aircraft systems, it will be necessary to have an insurance policy that covers liability against third parties for damages that may arise during and due to the execution of each flight that is carried out (both recreational and professional purposes) in accordance with articles 11 and 127 of the Air Navigation Law:

UAS with a MTOM equal to or greater than 20Kg for professional purposes must comply with Regulation 785/2004, and;

Professional UAS with MTOM equal to or less than 20Kg and those for recreational purposes must comply with the provisions of Royal Decree 37/2001, of January 19, which updates the amount of compensation for damages provided for in the Law of Air Navigation.

Regulation 785/2004 establishes a minimum amount for damages to third parties on land of 750,000 SDRs -Special Drawing Rights- (for drones of up to 500kg) while Royal Decree 37/2001 the minimum amount to cover is 220,000 SDRs.

Adequate insurance must be available to cover each flight made, and it is not necessary to contract a permanent policy.

*UAS Royal Decree project currently in process, which in its draft submitted for public consultation will exempt C0 class UAS and those without class marking with a maximum takeoff mass of less than 250 g operated in subcategory A1 from the compulsory insurance requirement.

Aeromodelling – Model airplanes and airplane modelers are subject to compliance with Execution Regulation (EU) 2019/947 applicable from December 31, 2020, provided that said flights are not carried out inside buildings or completely closed spaces.

However, in accordance with article 21.3 of Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947, model airplanes may continue to be practiced in accordance with national applicable regulations, the second, third and fifth additional provisions of Royal Decree 1036/2017, until 1 January 2023.

Regardless of the different options indicated below for the practice of model airplanes, all model airplane pilots must be registered as UAS operators whenever they intend to carry out flights:

With model airplanes that have a maximum takeoff mass (MTOM) greater than 250 grams or that, in the event of a collision, can transfer a kinetic energy greater than 80 joules to a human being (for example, “ racer ” drones).

With model aircraft that have sensors capable of capturing personal data and are not considered toys (according to Directive 2009/48/CE), such as with a photo or video camera of MTOM <250g, except toys.

In the ‘specific’ category (art. 14.5.b Reg.(UE) 2019/947).

Registration as a UAS operator is free and is done through the AESA electronic headquarters. To register, there are two options:

At an individual level (Electronic DNI, digital certificate or scanned DNI required), according to the instructions provided in the UAS/drones operator registration section of the AESA website.

Within the framework of a model airplane club or association, giving permission to the club or association to register them on their behalf. To this end, the following registration guide for model airplane clubs and associations is available:

Registration guide as a UAS operator for clubs and associations of model airplanes V2

The minimum age to register as a UAS operator is 16 years. For those users who are younger, they must operate under the protection of a registered UAS operator.

Regarding the registration of aircraft in the AESA application, there is only an obligation to register model aircraft when it is intended to operate in a “specific” category.

Currently, and during a transitional period until January 1, 2023, the practice of model airplanes in Spain can be carried out following any of the following 4 options, as long as the conditions defined in each of them are met and you are registered as an operator. of UAS as indicated in the previous section:

OPTION 0 (Transitional period)

Based on national regulations, operations may continue to be carried out without additional authorization until January 1, 2023. Modelers must:

Fly in the places authorized for it and comply with the conditions and limitations established by the clubs or associations.

The operational conditions indicated in additional provision 2 and 3 of Royal Decree 1036/2017 must be met , such as:

Refrain from carrying out any actions that may jeopardize the safety, regularity and continuity of aeronautical operations.

Limitation of maximum height above ground not greater than 400 ft ( 120 m ).

Daytime flights and under visual flight weather conditions. At night it is possible with UAS of MTOM < 2kg and height limited to 50 m above the ground.

Within pilot visual range ( VLOS ). In the case of use of first-person vision devices ( FPV ), it must be flown within the visual range of observers who remain in permanent contact with the pilot.

Operate at a minimum distance of 8 km from the reference point of any airport or aerodrome and the same distance with respect to the axes of the runways and their extension, in both headers, up to a distance of 6 km counted from the threshold in the direction of moving away from the runway or being coordinated with the infrastructure manager and ATS provider, if any.

For flights in controlled airspace and/or FIZ, prior coordination of the conditions of use with the air traffic service provider.

Installations that are affected by National Defense or State security or its security zone cannot be flown over.

Flight is not allowed in the vicinity of critical facilities and infrastructures.

The overflight of facilities and infrastructures of the chemical industry, transport, energy, water, and information and communication technologies must be carried out at a minimum height above them of 50 m and at a minimum horizontal distance of 25 m from their axis in the case of linear infrastructures. and no less than 10 m away from its outer perimeter in the rest of the cases.

For more information about the need for coordination of model airplane clubs or associations based on the location of their fields, they have at their disposal an informative note published on the AESA website:

Note for model airplane clubs v1.2

There is no training requirement beyond those established by the model airplane club or association.

There is no minimum age requirement for remote pilots operating under this option.

No limitation is established to the mass and dimensions of the model aircraft.

OPTION 1 Flights in the “open” category, meeting the particular requirements of subcategory A3 according to Regulation (EU) 2019/947

These flights must be carried out in areas where no non-participant person is endangered and at a minimum horizontal distance of 150 m from residential, commercial, industrial or recreational areas.

The model aircraft must have a maximum takeoff mass of less than 25 kg and the pilots must have passed the training and examination corresponding to the A1/A3 subcategory.

For more information on the operation requirements in subcategory A3

More information about the remote pilot training and exam in subcategory A1/A3

Regarding the minimum age of pilots who can fly in the `open` category, subcategory A3, said age is established at 16 years. However, there will be no minimum age as long as the remote pilot has the appropriate training and flies supervised by a UAS pilot who is 16 years of age or older.

OPTION 2 Flights in particular geographical areas

A UAS geographic zone is defined as a part of the airspace established by the competent authority that facilitates, restricts or excludes UAS operations in order to manage risks to safety, security, privacy, protection of personal data or environment. Pursuant to article 15 of Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947, the Inter ministerial Commission for Defense – Transport, Mobility and the Urban Agenda (CIDETMA), the competent body for airspace structuring, may designate geographical areas in which operations of UAS are exempt from one or several requirements of the “open” category.

OPTION 3 Authorization issued by the competent authority for UAS operations under the protection of a model airplane club or association

Depending on the operations to be carried out, if they cannot be framed within the open category (option 1), it will be necessary to issue an operational authorization issued by EASA at the request of a model airplane club or association.

In accordance with the provisions of article 16 of Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947, a model airplane club, association or federation may request EASA to issue an authorization to carry out operations with UAS within the framework of model airplane clubs or associations. aeromodelling.

By way of example, operations that would require an operational authorization would be the following:

-

-

- Carried out at a height greater than 120 m;

- Carried out with aircraft with an MTOM greater than 25 kg;

- Made with aircraft that are not privately manufactured and have a combustion system;

- That involve the overflight of concentrations of people;

- Conducted beyond the visual range of the pilot (BVLOS);

-

The authorizations that EASA may issue to model airplane clubs or associations shall be made in accordance with the procedures, organizational structure, and management system of the model airplane club or association, ensuring that:

-

-

- The pilots who fly within the framework of the club or association of model airplanes know the limitations and conditions defined in the authorization;

- The pilots who fly within the framework of the club or association of model airplanes receive assistance to reach the minimum competence that allows them to fly the UAS safely;

- The model airplane club or association takes the appropriate measures when it is aware that a pilot does not meet the conditions and limitations defined in the authorization;

- The model airplane club or association provides AESA with the necessary documentation for supervision and monitoring purposes.

-

The authorization issued by EASA will specify the conditions under which flight operations with model aircraft may be carried out within the scope of the club or association, including in each case the minimum age required of remote pilots. Said authorization will be limited to the national territory.

To request an authorization for UAS operations within the framework of model airplane clubs and associations, the interested party may direct his request to the AESA UAS Division through the procedure enabled for that purpose. In any case, the application must be made by the model airplane club, association or federation, attaching the documentation that meets the requirements established in article 16 of the Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947. A guide for submitting authorization requests is made available to clubs or associations at the following link:

Operational authorization presentation guide for model airplanes v1

For more information regarding the practice of model airplanes, you can consult the following presentation:

Presentation on the practice of model airplanes with the new regulatory framework v1

For any questions about these issues, you can contact AESA through the following email address: drones.aesa@seguridadaerea.es

Drone/UAS Operator Registration

IMPORTANT: Information regarding the expiration date of the UAS operator registration certificate

With the entry into application of the Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947 of the Commission on December 31, 2020, all UAS operators * who intend to carry out both recreational and professional activities (including model airplanes) must register as an operator ** when using any of the following types of UAS:

Use in the ‘open’ category any unmanned aircraft:

With a MTOM of 250 g or more, or which, in the event of a collision, can transfer to a human being a kinetic energy greater than 80 joules;

equipped with a sensor capable of capturing personal data, unless it is in compliance with Directive 2009/48/EC (“Toys Directive”).

Use an unmanned aircraft of any mass in the ‘specific’ category.

In clarification of the previous points of registration requirements as an operator for UAS of reduced weight, more information is provided in the following document: Information on drones of less than 250g .

A UAS operator is any natural or legal person who uses or intends to use one or more UAS, both for professional and recreational purposes (including model aeroplanes).

The registration must be made in the Member State of residence or where the economic activity is carried out, and it is not possible to be registered in more than one State at the same time.

Registration as a UAS operator in AESA is free and is done through its electronic headquarters ( link to the procedure ). This procedure will be automatic and immediate if a digital certificate is used.

Obtaining the UAS operator code (registration as a UAS operator) is also mandatory for operators authorized based on Law 18/2014 and Royal Decree 1036/2017 (except NON-EASA activities).

The generated UAS operator registration number shall be included in all the operator’s drones.

Only in the case that you are going to carry out operations in the ‘specific’ declaration or LUC category, it is necessary to enter the UAS in the UAS operator profile. There is an explanatory video that serves as a guide for the UAS operator in the UAS/Drones Operations – Specific Category section

Remember the need to have an insurance policy that covers civil liability against third parties for damages that may arise during and due to the execution of each flight that is carried out, both for recreational and professional purposes. More information on insurance in the section on European regulations for drones/UAS

The following guide and video detail the instructions to follow to register as a UAS operator:

Important note : The “APPROVED” user registration does not imply registration as a UAS operator. It is necessary to access the UAS application and register as a UAS operator within a maximum period of 30 days after user registration; Otherwise, the system will delete the user, having to carry out this procedure again.

*Except for non-EASA activities (Fire fighting, search and rescue, police, customs, etc.)

**or if you have been hired as a remote pilot or fly for someone else, in which case the drone operating organization must register.

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM)

2022 – Spain tests urban air mobility with air taxis, drones and conventional aviation

2022 – UMILES Next’s eVTOL flies in Spain to test UAM airspace integration concepts

2023 – 1st operational European urban vertiport to be built in Zaragoza

2023 – Spain tests urban air mobility with air taxis, drones and conventional aviation

2023 – EHang Inaugurates Its European Urban Air Mobility Center for Unmanned eVTOLs

2024 – Development of UAM Pilot Project in Spain

2024 – Unifly’s UTM Platform Advances Urban Air Mobility in Europe

Short Essay Questions

Question 1

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film in Barcelona, pictured above.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Question 2

Do you need a certificate to fly UAS?

If so, how do you obtain one?

Are there fees associated with this?

If so, how much?

Question 3

May you operate beyond visual line of sight?

If so, what procedures must you follow?

Question 4

Does the country have UAM/AAM laws? If so, describe, citing the exact law.

Question 5

Are you aware of any new laws or policies not mentioned above? If so, describe, citing the exact law or policy.