160 Philippines

Two equal horizontal bands of blue (top) and red. A white equilateral triangle is based on the hoist side. The center of the triangle displays a yellow sun with eight primary rays. Each corner of the triangle contains a small, yellow, five-pointed star. Blue stands for peace and justice, red symbolizes courage, the white equal-sided triangle represents equality. The rays recall the first eight provinces that sought independence from Spain, while the stars represent the three major geographical divisions of the country: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The design of the flag dates to 1897.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

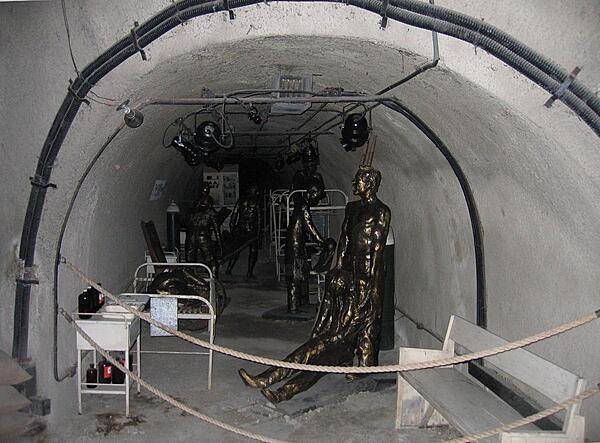

East entrance to the Malinta Tunnel complex on the island of Corregidor. Constructed by the US Army Corps of Engineers between 1922 and 1932, it was used for bomb-proof storage, as a command center, and a 1,000-bed hospital. The main east-west tunnel is 253 m (830 ft) long and 7.3 m (24 ft) wide, with 24 lateral tunnels, each about 49 m (160 ft) long and 4.6 m (15 ft) wide. A double track electric railway ran down the main tunnel. General Douglas MACARTHUR’s headquarters and the offices of President Manuel L. QUEZON of the Philippines Commonwealth were located in laterals just inside this entrance. Certain lateral tunnels of the Malinta Tunnel complex present dioramas that show what life was like inside the tunnels. This display represents one of the hospital laterals and depicts the treatment of wounded.

Photos courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, the Philippines has been governed under three constitutions, the first of which was promulgated in 1935, during the period of US administration. It was closely modeled on the US Constitution and included provisions for a bicameral legislative branch, an executive branch headed by a president, and an independent judiciary. During the period of martial law (1972–81) under President Ferdinand E. Marcos, the old constitution was abolished and replaced by a new document (adopted in January 1973) that changed the Philippine government from a U.S.-style presidential system to a parliamentary form. The president became head of state, and executive power was vested in a prime minister and cabinet. President Marcos, however, also served (until 1981) as prime minister and ruled by decree. Subsequent amendments and modifications of that constitution replaced the former bicameral legislature with a unicameral body and gave the president even more powers, including the ability to dissolve the legislature and (from 1981) to appoint a prime minister from among members of the legislature.

After the downfall of Marcos in 1986, a new constitution similar to the 1935 document was drafted and was ratified in a popular referendum held in February 1987. Its key provision was a return to a bicameral legislature, called the Congress of the Philippines, consisting of a House of Representatives (with about 290 members) and a much smaller Senate (some two dozen members). House members are elected from districts, although a number of them are appointed; they can serve no more than three consecutive three-year terms. Senators, elected at large, can serve a maximum of two six-year terms. The first legislative election under the new constitution was held in May 1987. The president, the head of state, can be elected to only a single six-year term and the vice president to two consecutive six-year terms. The president appoints the cabinet, which consists of the heads of the various ministries responsible for running the day-to-day business of the government. Most presidential appointments are subject to the approval of a Commission of Appointments, which consists of equal numbers of senators and representatives.

Before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, most people lived in small independent villages called barangays, each ruled by a local paramount ruler called a datu. The Spanish later founded many small towns, which they called poblaciones, and from those centers roads or trails were built in four to six directions, like the spokes of a wheel. Along the roadsides arose numerous new villages, designated barrios under the Spanish, that were further subdivided into smaller neighborhood units called sitios.

Elements of both Spanish and indigenous local settlement structures have persisted into the early 21st century. The country is divided administratively into several dozen provinces, which are grouped into a number of larger regions. The National Capital Region (Metro Manila) has special status, as does the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao in the far south. Each province is headed by an elected governor. The provinces collectively embrace more than 100 cities and some 1,500 municipalities. The poblaciones are now the central business and administrative districts of larger municipalities.

Although contemporary rural and urban settlement revolves around the poblaciones, the population is typically concentrated in the surrounding barangays, reinstated during the Marcos regime as the basic units of government (replacing the barrios). The barangays, which number in the tens of thousands, consist of communities of fewer than 1,000 residents that fall within the boundaries of a larger municipality or city. Cities, municipalities, and barangays all have elected officials.

The constitution of 1987, which reestablished the independence of the judiciary after the Marcos regime, provides for a Supreme Court with a chief justice and 14 associate justices. Supreme Court justices are appointed by the president from a list submitted by the Judicial and Bar Council and serve until they reach the age of 70. Lower courts include the Court of Appeals; regional, metropolitan, and municipal trial courts; and special courts, including the Court of Tax Appeals, Shariʿa (Sharīʿah) district and circuit courts of Islamic law, and the Sandiganbayan, a court for trying cases of corruption. Because justices and judges enjoy fixed tenure and moderate compensation, the judiciary has generally been less criticized than other branches of the government. However, the system remains challenged by lack of fiscal autonomy and an extremely low budget that long has amounted to just a tiny fraction of total government spending.

In order to reduce the load of the lower courts, local committees of citizens called Pacification Committees (Lupon Tagapamayapa) have been organized to effect extrajudicial settlement of minor cases between barangay residents. In each lupon (committee) there is a Conciliation Body (Pangkat Tagapagkasundo), the main function of which is to bring opposing parties together and effect amicable settlement of differences. The committee cannot impose punishment, but otherwise its decisions are binding.

Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP)

The Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP) was created by virtue of Republic Act No. 9497 which was approved on March 4, 2008. Under Chapter 1, Section 2 of said Republic Act, (Declaration of Policy), it is declared the policy of the State “to provide safe and efficient air transport and regulatory services in the Philippines by providing for the creation of a civil aviation authority with jurisdiction over the restructuring of the civil aviation system, the promotion, development and regulation of the technical, operational, safety, and aviation security functions under the civil aviation authority”.’ The creation of CAAP in 2008 is the main component of an intensive civil aviation reform program launched by the government. According to Chapter 1, Sec. 4 (Creation of the Authority), CAAP is “an independent regulatory body with quasi-judicial and quasi legislative powers and possessing corporate attributes attached to the Department of Transportation and Communication (DOTC) for the purpose of policy coordination”. The same provision also abolished the existing Air Transportation Office created under the provisions of Republic Act No. 776, as amended. To ensure availability of technically qualified and currently qualified personnel, the Act empowers CAAP to update its standards, system and procedures prescribed for civil aviation inspectorate, licensing, and oversight functions to comply with ICAO and other international aviation standards. It is allowed flexibility to incorporate new practices and procedures as they become available without the procedures required for promulgation of legally binding regulations (part 1 General Policies, Procedures and Definitions, PCAR). Pursuant to Chapter II, Sec. 15, CAAP shall enjoy fiscal autonomy. All moneys earned by the Authority from the collection / levy of any and all such fees, charges, dues, assessments and fines it is empowered to collect / levy under this Act shall be used solely to fund the operations of the Authority.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

Drone Regulations

Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems

AC 11-001 Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

2024 – AMSL Aero, BCDA partner on hydrogen production in Philippines

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film people entering the tunnel, pictured above.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?