43 New Zealand

Blue with the flag of the UK in the upper hoist-side quadrant with four red five-pointed stars edged in white centered in the outer half of the flag. The stars represent the Southern Cross constellation.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

The 328 m (1,076 ft) observation and telecommunications Sky Tower in Auckland is the tallest free-standing structure in the Southern Hemisphere.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, New Zealand has a parliamentary form of government based on the British model. Legislative power is vested in the single-chamber House of Representatives (Parliament), the members of which are elected for three-year terms. The political party or coalition of parties that commands a majority in the House forms the government. Generally, the leader of the governing party becomes the prime minister, who, with ministers responsible for different aspects of government, forms a cabinet. The cabinet is the central organ of executive power. Most legislation is initiated in the House on the basis of decisions made by the cabinet; Parliament must then pass it by a majority vote before it can become law. The cabinet, however, has extensive regulatory powers that are subject to only limited parliamentary review. Because cabinet ministers sit in the House and because party discipline is customarily strong, legislative and executive authorities are effectively fused. The British monarch is the formal head of state and is represented by a governor-general appointed by the monarch (on the recommendation of the New Zealand government) to a five-year term. The governor-general has limited authority, with the office retaining some residual powers to protect the constitution and to act in a situation of constitutional crisis. For example, the governor-general can dissolve Parliament under certain circumstances.

The structure of the New Zealand government is relatively simple, but the country’s constitutional provisions are more complex. Like that of Great Britain, New Zealand’s constitution is a mixture of statute and convention. Where the two clash, convention has tended to prevail. The Constitution Act of 1986 simplified that by consolidating and augmenting constitutional legislation dating from 1852.

The business of government is carried out by some 30 departments of varying size and importance. Most departments correspond to a ministerial portfolio, department heads being responsible to their respective ministers for the administration of their departments. Recruiting and promoting of civil servants is under the control of the State Services Commission, which is independent of partisan politics. Heads of departments and their officials do not change with a change of government, thus ensuring a continuity of administration.

As a check on possible administrative injustices, an office of parliamentary commissioner for investigations (ombudsman) was established in 1962; the scope of the office’s jurisdiction was enlarged in 1968 and again in 1975. In addition, the Official Information Act of 1982 permits public access, with specific exceptions, to government documents.

There are also a certain number of non-civil-service appointees within the government. They fill positions in government corporations, commercial ventures in which the government is the sole or major stockholder, such as NZ On Air (the government’s broadcast funding agency) and Kiwibank (which provides commercial banking and financial services), and in a host of bodies with administrative or advisory functions. Political affiliations, as well as expertise and experience, often figure in appointment decisions for those institutions.

Local government bodies consist of elected councils at the regional and city levels together with specialist and community boards. Those entities have limited powers conferred by statute. The responsibilities of the city councils include the provision of community services and local infrastructure and the management of resources and the local environment. Regional councils carry out larger environmental and infrastructure functions requiring coordination (such as water quality, flood control, civil defense, and transportation planning). Community boards serve as a liaison between the people of the community and local authorities. They are made up of elected members; it is also common, though not obligatory, for a smaller number of additional members to be appointed. Elections for local government bodies are contested every three years.

Over time, many councils and boards have been consolidated by the central government into larger authorities. A major amalgamation brought together several cities and their councils in the Auckland region in 2010. City and regional councils are empowered within their jurisdictions to levy taxes on business and property owners, debate and approve plans, and manage a large range of facilities and services. In the case of Auckland, new entities controlled by the city council have been created to manage major infrastructure development and facilities.

New Zealand derives from the common law of Britain certain statutes passed before 1947 by the British Parliament. New Zealand law usually follows the precedents of English law. Nevertheless, the New Zealand courts have taken a more independent stance and now play a significant constitutional and political role with respect to public and administrative law. In addition, some members of the legal community have challenged the traditional doctrine that future Parliaments are not bound by laws passed by the current Parliament, contending that certain common-law rights might override the will of Parliament.

The law is administered by the Ministry of Justice through its courts. A Supreme Court was established by legislation in 2003 (hearings began in 2004), replacing the British Privy Council. Below the Supreme Court there is a hierarchy of courts dealing with civil and criminal cases, including—in ascending order—District Courts, the High Court, and the Court of Appeal. There are also environment and employment courts, a Māori Land Court and a Māori Appellate Court, and a number of tribunals, including the Waitangi Tribunal, which addresses Māori claims of breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi by the government.

Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand

The Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand is a Crown entity responsible to the Minister of Transport. Civil aviation in New Zealand operates within a system established and maintained by the Civil Aviation Act 1990. They are governed by the Authority – a five member board appointed by the minister to represent the public interest in civil aviation. The Authority appoints our chief executive, who is also the Director of Civil Aviation. As well as the functions and powers delegated by the Authority, the Director has powers conferred by the Act, which are performed independently of both the Minister of Transport and the Authority. The Authority is also responsible for the governance of the Aviation Security Service. They are funded by a number of sources, including a small levy on airlines, based on their number of passengers per sector. We also charge for our services, including those provided to the Government.

Pacific Aviation Safety Office (PASO)

The Pacific Aviation Safety Office (PASO) is an international organization providing quality aviation safety and security service for Member States in the Pacific.

PASO is the sole international organization responsible for regional regulatory aviation safety oversight service for the 10 Pacific States who are signatories to the Pacific Islands Civil Aviation Safety and Security Treaty (PICASST).

The current PICASST signatories are the Pacific nations of Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. Associate Members of PASO are Australia, Fiji and New Zealand. Government representatives from these nations make up the PASO Council.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

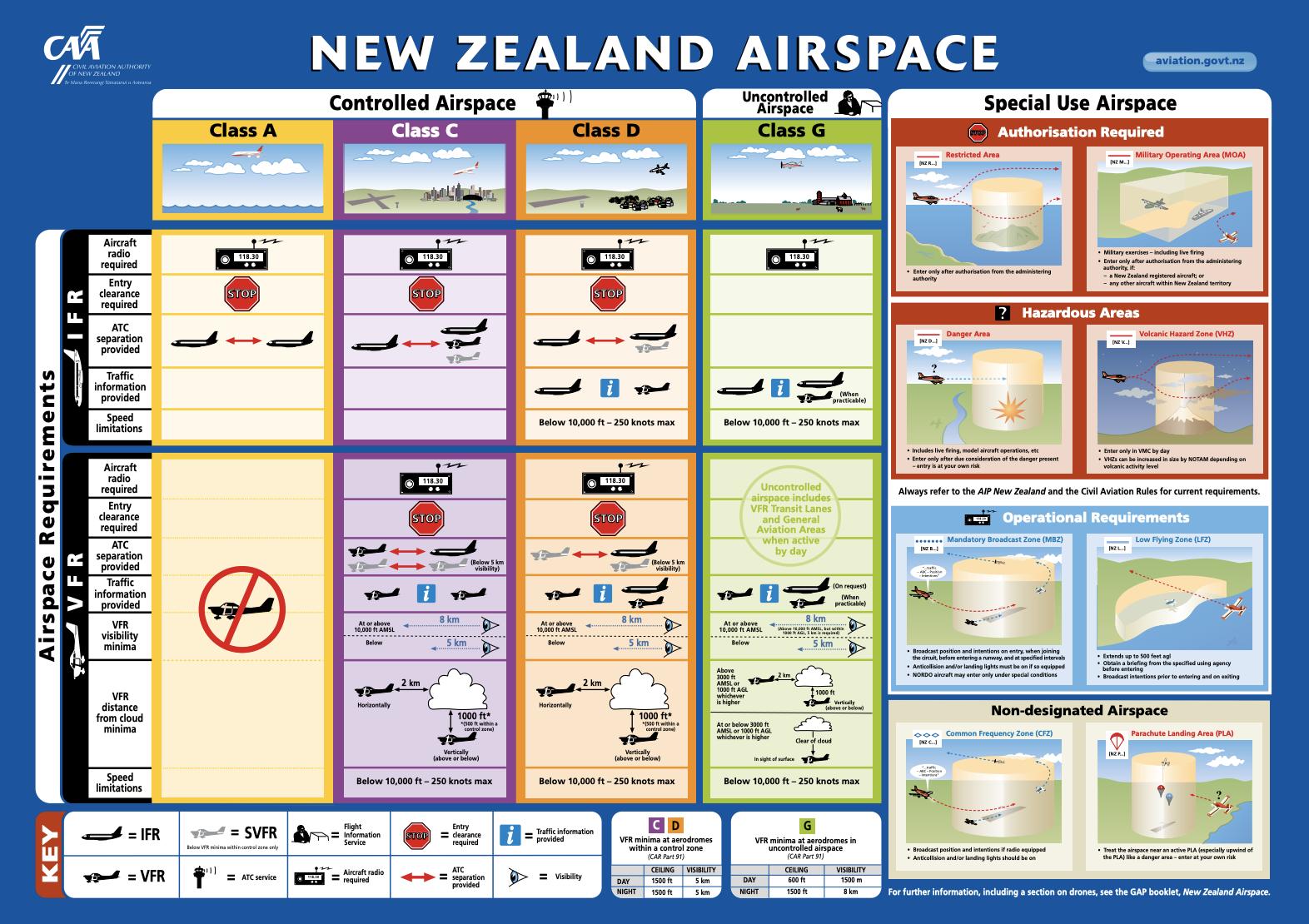

In New Zealand, the Civil Aviation Authority publishes a document explaining airspace in more detail and defining airspace.

Drone Regulations

Part 101 rules when flying your unmanned aircraft

Intro to Part 102 certification for unmanned aircraft

Department of Conservation – Apply for a recreational drone concession

C-UAS

According to the New Zealand Ministry of Transport (NZMOT), the Civil Aviation Act 1990 governs New Zealand’s civil aviation system and sets the overall framework for aviation safety, security and economic regulation. The Airport Authorities Act 1966 gives airport authorities a range of functions and powers to establish and operate airports. The Acts have been amended several times, but not substantially revised.

The aviation industry and the government regulatory environment have changed since the Acts came into effect. In 2014, NZMOT reviewed the Acts to ensure they were still fit for purpose, and then consulted stakeholders. They used that feedback to draft a new Bill to replace the Acts and in 2019 we consulted on a draft of the Bill. Between September 2021 and April 2023, the Bill passed through the Parliamentary process, including being considered by the Transport and Infrastructure Select Committee.

On 5 April 2023, the Civil Aviation Bill received Royal assent and became the Civil Aviation Act 2023. The new Act will be in force from 5 April 2025.

- There’s a range of changes that the new Act will bring in, including: A new registration regime for airports, including a requirement for airports to consult on their spatial plans.

- For Tier 1 airports, they’ll be bringing in the Regulatory Airport Spatial Undertakings outlined in the Bill.

- Setting up the new independent review process function for decisions made by the Director of Civil Aviation.

- Development of rules and guidance for drug and alcohol management plans that some operators will be required to prepare. These future plans will include providing random testing of those working in safety sensitive activities.

NZMOT will also be working to realign the Civil Aviation Rules with the 2023 Act and make regulations necessary to support the civil aviation regulatory system.

Over the next 24 months, they will be working on the implementation of the Act, alongside their colleagues at the Civil Aviation Authority.

More information on the contents of the Civil Aviation Act 2023 can be found on the Parliament website.

Specifically, Part 5 deals with Aviation Security.

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

Bilateral agreements facilitate the reciprocal airworthiness certification of civil aeronautical products imported/exported between two signatory countries. A Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement (BAA) or Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement (BASA) with Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA) provides for airworthiness technical cooperation between the FAA and its counterpart civil aviation authorities.

Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement – Executive Agreement

Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness

2016 Notification of Policy Deviation Memorandum for FAA Order 8130.21H

Obtaining Certification Approval from this Country

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

2025 – Hydrogen Fuelling Now On Tap At New Zealand’s Christchurch Airport

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the July 2025 Global AAM Forum.

2025 – Air New Zealand and BETA Technologies launch the first “Energy by Hour” maintenance program

2025 – Autonomous Merlin Pilot Wins Airworthiness Approval in New Zealand

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 2 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

2024 – Air New Zealand Orders Beta Alia CX300 Demonstrator Aircraft

2024 – Air New Zealand expands order and partnership with Beta Technologies

2024 – Life Flight becomes AMSL Aero’s first New Zealand development partner for Vertiia aircraft

2024 – Wellington Airport Selected as Home Base of New Zealand’s First All-Electric Service

2024 – Air New Zealand to Fly Amazon-Backed Electric Plane in 2026

2023 – Air New Zealand will operate BETA’S ALIA Electric Aircraft from 2026

2023 – Air New Zealand announces Beta’s Alia as launch aircraft for Mission Next Gen Aircraft program

2023 – CAA and Industry launch new emerging aviation technologies forum

2022 – Bringing autonomous AAM to New Zealand through Airspace Integration Trials

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone in Auckland.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?