154 Mongolia

Three, equal vertical bands of red (hoist side), blue, and red. Centered on the hoist-side red band in yellow is the national emblem (“soyombo” – a columnar arrangement of abstract and geometric representation for fire, sun, moon, earth, water, and the yin-yang symbol). Blue represents the sky, red symbolizes progress and prosperity.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

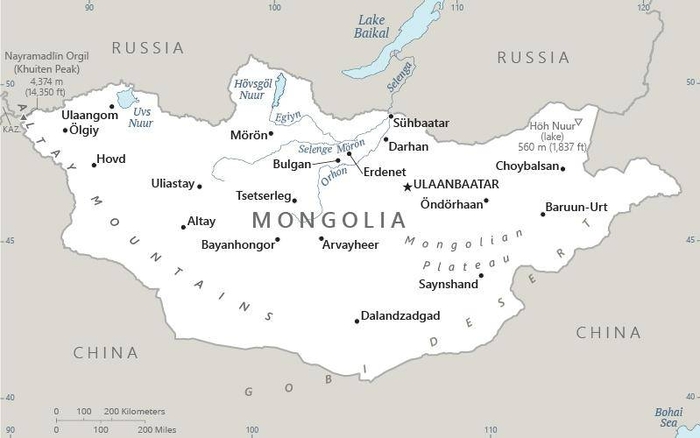

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Genghis Khan, the first Mongol Emperor

Government

According to Britannica, after the victory of the Soviet-backed revolution in Mongolia in July 1921, the Mongolian People’s Party (MPP; founded 1920) gradually consolidated its power. In 1924 the MPP formed a national assembly called the State Great Khural, which adopted the country’s first constitution and proclaimed the foundation of the Mongolian People’s Republic. The MPP—subsequently renamed the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP), a communist party in all but name—transformed Mongolia gradually into a command economy with state ownership of the means of production. In 1960 the national assembly was renamed the People’s Great Khural, and its structure and activity were brought closer to those of the Supreme Soviet model in the Soviet Union.

During the 1980s, when the Soviets began calling for reform and more openness in their society, the MPRP began to tolerate some criticism of the party leadership’s policies. Quasi-political “informal” associations grew active in Ulaanbaatar (Ulan Bator) and by the end of the decade were challenging the MPRP’s one-party rule. In March 1990, under increasing public pressure, the MPRP leaders resigned. The new leaders conceded constitutional changes, including legalizing political parties, creating a standing legislature and the office of the president, and providing for elections to a new People’s Great Khural later that year. In July, for the first time, non communists were elected to the assembly, although a large MPRP majority still controlled it. However, the new government included several ministers from newly established democratic parties who sat in the State Little Khural, the standing legislature based on proportional representation.

The People’s Great Khural drafted and adopted a new constitution (Mongolia’s fourth), which went into effect on February 12, 1992. Power is divided among independent legislative, executive, and judicial branches, with human rights guaranteed by law. Capital punishment, though still on the statute books, was suspended by the president in February 2010, pending abolition. The state permits the private ownership of land (other than pastures) but retains control over water, forest, fauna, and underground resources. The constitution created a new unicameral legislature, the Mongolian Great Khural (MGK), the members of which are elected for four-year terms. The constitution also provides for a directly elected president, who is head of state and who, on the advice of the majority party leader in the MGK, nominates the prime minister, who is head of government. The president may initiate or veto legislation, but by a two-thirds vote the MGK can override a presidential veto. The government is formed by the prime minister in consultation with the president and with the approval of the MGK.

The constitution was amended in 2001, mainly to simplify the procedure for appointment of prime ministers and shorten the minimum length of parliamentary sessions, and again in 2019, which included modifications to the presidential term and changes that enhanced the powers of the prime minister. Amendments to the constitution must be supported by three-fourths of the MGK’s members. Observance of the constitution is supervised by a Constitutional Commission consisting of nine members who serve for six-year terms.

The country is divided administratively into 21 aimags (provinces) and the hot (municipality) of Ulaanbaatar, which has independent administrative status. The provinces are headed by governors, appointed by the prime minister, and local assembly (khural) chairmen, elected in local government elections, held every four years. The governor of Ulaanbaatar municipality is also mayor of the city. The provinces are subdivided into sums (districts) and bags (subdistricts), and Ulaanbaatar consists of several düüreg (urban districts). The provincial-level government structure is repeated at these lower levels. The governors and assembly chairmen of the provinces and Ulaanbaatar are relatively powerful, with their own administrations and budgets.

Justice is administered through an independent system of courts: the Supreme Court, provincial courts (including a capital city court), district courts, and courts of appeal. The Supreme Court, headed by the chief justice, appointed for a six-year term, has three chambers, of criminal, civil, and administrative law, each headed by a senior judge. The chief justice also chairs the General Council of Courts, which supervises court work. Judges are appointed and dismissed by the president.

Civil Aviation Authority (CAA)

In 1997, the Civil Aviation Administration become an Implementing agency of government of Mongolia. In 1999, the Civil Aviation Administration changed its name to the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). The main goals are:

- Development of civil aviation sector;

- Availability of flight and aviation safety;

- Upgrade the technology, material base, air traffic control, land relations, navigational and electrical equipment and expand the aerodrome and airport;

- Train and trained professional personnel;

- Financial capacity;

- Improve the use of airspace; and

- Increase the number of foreign airlines flying over the territory of Mongolia.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

Drone Regulations

AC 102-1 Unmanned Aircraft-Operator Certification

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

None found by the author.

However, should you, the reader, happen to stumble across something to the contrary, please email the author at FISHE5CA@erau.edu and you may be mentioned in the ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS section of this book by way of thanks for contributing to this free eBook!

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

None found by the author.

However, should you, the reader, happen to stumble across something to the contrary, please email the author at FISHE5CA@erau.edu and you may be mentioned in the ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS section of this book by way of thanks for contributing to this free eBook!

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film the Genghis Khan Statue Complex which lies around 50 kilometers outside of Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?