122 Isle of Man (UK)

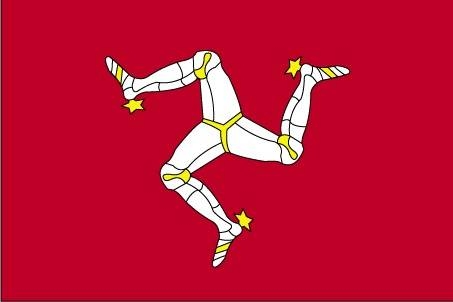

Red with the Three Legs of Man emblem (triskelion), in the center. The three legs are joined at the thigh and bent at the knee. In order to have the toes pointing clockwise on both sides of the flag, a two-sided emblem is used. The flag is based on the coat of arms of the last recognized Norse King of Mann, Magnus III (r. 1252-65). The triskelion has its roots in an early Celtic sun symbol.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

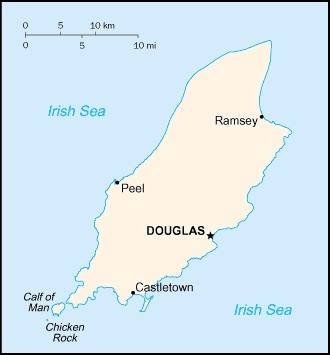

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

The Isle of Man is a small island with a complex geologic history. Geologists have studied and reported on the Isle of Man since the 19th century, making it a popular destination for rock hounds. Roughly 50 km (30 mi) from northeast to southwest, the island preserves rock layers dating back hundreds of millions of years. While most of the rocks are covered by soil, some rock layers exposed at the surface, along the coast, and in quarries have shed light on this island’s assorted ancient landscapes. This natural-color satellite image of the Isle from 1 May 2001 shows the northern end of the island; the image has been rotated so north is to the right. Croplands cover the relatively flat terrain of the northern coastal plain, which forms a rough triangle. Underlying the fields are glacial sediments. Between 70,000 and 10,000 years ago, a giant ice sheet covered the Isle of Man. The ice advanced and retreated multiple times, occasionally piling up rocks to form hills. As the ice melted, all the dirt and debris locked within it came to rest on the northern plain. Toward the south, the land rises. The rock layers in this region are collectively known as the Manx Group; they make up the bulk of the Isle of Man, and comprise a mixture of sedimentary and volcanic rocks, folded and faulted by millions of years of tectonic pressures. They are far older than the glacial sediments coating the northern plain, having been formed between 490 million and 470 million years ago at the bottom of an ancient sea floor. Visible from the sky, the uneven contours of these rock layers hint at their complicated history.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Last updated on October 24, 2025

Government

According to Britannica, the government consists of an elected president; a Legislative Council, or upper house; and a popularly elected House of Keys, or lower house. The two houses function as separate legislative bodies but come together to form what is known as the Tynwald Court to transact legislative business. The House of Keys constitutes one of the most ancient legislative assemblies in the world. The Isle of Man levies its own taxes.

Isle of Man Civil Aviation Administration (IOMCAA)

The Isle of Man Civil Aviation Administration (IOMCAA) contains links to aviation legislation and other documents that provide information and guidance on the safety and security of civil aviation in the Isle of Man. The IOMCAA is the division of the Government’s Department for Enterprise that is responsible for regulating aviation safety and security in the Isle of Man. The IOMCAA also administers the Isle of Man Aircraft Registry and regulates the Isle of Man Airport and is responsible for ensuring aviation legislation in the Isle of Man meets ICAO Standards and Recommended Practices and other relevant European aviation standards. The CAA may from time to time issue permissions and exemptions to aviation legislation.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

Isle of Man AIP – requires user name and password

Drone Regulations

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

None found by the author.

However, should you, the reader, happen to stumble across something to the contrary, please email the author at FISHE5CA@erau.edu and you may be mentioned in the ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS section of this book by way of thanks for contributing to this free eBook!

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

None found by the author.

However, should you, the reader, happen to stumble across something to the contrary, please email the author at FISHE5CA@erau.edu and you may be mentioned in the ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS section of this book by way of thanks for contributing to this free eBook!

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film the Peel Castle on the Isle of Man.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?