79 Germany

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Winter view of Neuschwanstein Castle as seen from the Marienbruecke (Mary’s Bridge). This castle is the best known of the three royal palaces built by King Ludwig II of Bavaria. The design and decoration of the castle pay homage to various medieval legends.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, the structure and authority of Germany’s government are derived from the country’s constitution, the Grundgesetz (Basic Law), which went into force on May 23, 1949, after formal consent to the establishment of the Federal Republic (then known as West Germany) had been given by the military governments of the Western occupying powers (France, the United Kingdom, and the United States) and upon the assent of the parliaments of the Länder (states) to form the Bund (federation). West Germany then comprised 11 states and West Berlin, which was given the special status of a state without voting rights. As a provisional solution until an anticipated reunification with the eastern sector, the capital was located in the small university town of Bonn. On October 7, 1949, the Soviet zone of occupation was transformed into a separate, nominally sovereign country (if under Soviet hegemony), known formally as the German Democratic Republic (and popularly as East Germany). The five federal states within the Soviet zone were abolished and reorganized into 15 administrative districts (Bezirke), of which the Soviet sector of Berlin became the capital.

Full sovereignty was achieved only gradually in West Germany; many powers and prerogatives, including those of direct intervention, were retained by the Western powers and devolved to the West German government only as it was able to become economically and politically stable. West Germany finally achieved full sovereignty on May 5, 1955.

East Germany regarded its separation from the rest of Germany as complete, but West Germany considered its eastern neighbor as an illegally constituted state until the 1970s, when the doctrine of “two German states in one German nation” was developed. Gradual rapprochements between the two governments helped regularize the anomalous situation, especially concerning travel, transportation, and the status of West Berlin as an exclave of the Federal Republic. The dissolution of the communist bloc in the late 1980s opened the way to German unification.

As a condition for unification and its integration into the Federal Republic, East Germany was required to reconstitute the five historical states of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg–West Pomerania, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. As states of the united Germany, they adopted administrative, judicial, educational, and social structures parallel and analogous to those in the states of former West Germany. East and West Berlin were reunited and now form a single state.

With the country’s unification on October 3, 1990, all vestiges of the Federal Republic’s qualified status as a sovereign state were voided. For example, Berlin was no longer technically occupied territory, with ultimate authority vested in the military governors.

Germany’s constitution established a parliamentary system of government that incorporated many features of the British system; however, since the Basic Law created a federal system, unlike the United Kingdom’s unitary one, many political structures were drawn from the models of the United States and other federal governments. In reaction to the centralization of power during the Nazi era, the Basic Law granted the states considerable autonomy. In addition to federalism, the Basic Law has two other features similar to the Constitution of the United States: (1) its formal declaration of the principles of human rights and of bases for the government of the people and (2) the strongly independent position of the courts, especially in the right of the Federal Constitutional Court to void a law by declaring it unconstitutional.

The formal chief of state is the president. Intended to be an elder statesman of stature, the president is chosen for a five-year term by a specially convened assembly. In addition to formally signing all federal legislation and treaties, the president nominates the federal chancellor and the chancellor’s cabinet appointments, whom the president may dismiss upon the chancellor’s recommendation. However, the president cannot dismiss either the federal chancellor or the Bundestag (Federal Diet), the lower chamber of the federal parliament. Among other important presidential functions are those of appointing federal judges and certain other officials and the right of pardon and reprieve.

The government is headed by the chancellor, who is elected by a majority vote of the Bundestag upon nomination by the president. Vested with considerable independent powers, the chancellor is responsible for initiating government policy. The cabinet and its ministries also enjoy extensive autonomy and powers of initiative. The chancellor can be deposed only by an absolute majority of the Bundestag and only after a majority has been assured for the election of a successor. This “constructive vote of no confidence”, in contrast to the vote of no confidence employed in most other parliamentary systems, which only require a majority opposed to the sitting prime minister for ouster, reduces the likelihood that the chancellor will be unseated. Indeed, the constructive vote of no confidence has been used only once to remove a chancellor from office (in 1982 Helmut Schmidt was defeated on such a motion and replaced with Helmut Kohl). The cabinet may not be dismissed by a vote of no confidence by the Bundestag. The president may not unseat a government or, in a crisis, call upon a political leader at his discretion to form a new government. The latter constitutional provision is based on the experience of the sequence of events whereby Adolf Hitler became chancellor in 1933.

Most cabinet officials are members of the Bundestag and are drawn from the majority party or proportionally from the parties forming a coalition, but the chancellor may appoint persons without party affiliation but with a certain area of technical competence. These non delegate members speak or answer questions during parliamentary debates.

The Bundestag, which consists of about 600 members (the precise number of members varies depending on election results), is the cornerstone of the German system of government. It exercises much wider powers than the 69-member upper chamber, known as the Bundesrat (Federal Council). Bundesrat delegations represent the interests of the state governments and are bound to vote unanimously as instructed by their provincial governments. All legislation originates in the Bundestag; the consent of the Bundesrat is necessary only on certain matters directly affecting the interests of the states, especially in the area of finance and administration and for legislation in which questions of the Basic Law are involved. It may restrain the Bundestag by rejecting certain routine legislation passed by the lower chamber; unless a bill falls within certain categories that enable the Bundesrat to exercise an absolute veto over legislation, its vote against a bill may be overridden by a simple majority in the Bundestag, or by a two-thirds majority in the Bundestag should there be a two-thirds majority opposed in the Bundesrat. To amend the Basic Law, approval by a two-thirds vote in each chamber is required.

The powers of the Bundestag are kept in careful balance with those of the Landtage, the state parliaments. Certain powers are specifically reserved to the republic—for example, foreign affairs, defense, post and telecommunications, customs, international trade, and matters affecting citizenship. The Bundestag and the states may pass concurrent legislation in such matters when it is necessary and desirable, or the Bundestag may set out certain guidelines for legislation; drawing from these, each individual Landtag may enact legislation in keeping with its own needs and circumstances. In principle, the Bundestag initiates or approves legislation in matters in which uniformity is essential, but the Landtage otherwise are free to act in areas in which they are not expressly restrained by the Basic Law.

Certain functions (e.g., education and law enforcement) are expressly the responsibility of the states, yet there is an attempt to maintain a degree of uniformity among the 16 states through joint consultative bodies. The state governments are generally parallel in structure to that of the Bund but need not be. In 13 states the head of government has a cabinet and ministers; each of these states also has its own parliamentary body. In the city-states of Hamburg, Bremen, and Berlin, the mayor serves simultaneously as the head of the city government and the state government. In the city-states the municipal senates serve also as provincial parliaments, and the municipal offices assume the nature of provincial ministries.

The administrative subdivisions of the states (exclusive of the city-states and the Saarland) are the Regierungsbezirke (administrative districts). Below these are the divisions known as Kreise (counties). Larger communities enjoy the status of what in the United Kingdom was formerly the county borough. The counties themselves are further subdivided into the Gemeinden (roughly “communities” or “parishes”), which through long German tradition have achieved considerable autonomy and responsibility in the administration of schools, hospitals, housing and construction, social welfare, public services and utilities, and cultural amenities. Voters may pass laws on certain issues via referenda at the municipal and state levels.

The German court system differs from that of some other federations, such as the United States, in that all the trial and appellate courts are state courts while the courts of last resort are federal. All courts may hear cases based on law enacted on the federal level, though there are some areas of law over which the states have exclusive control. The federal courts assure the uniform application of national law by the state courts. In addition to the courts of general jurisdiction for civil and criminal cases, the highest of which is the Federal Court of Justice, there are four court systems with specialized jurisdiction in administrative, labour, social security, and tax matters. The jurisdiction of the three-level system of administrative courts extends, for example, to all civil law litigation of a non constitutional nature unless other specialized courts have jurisdiction.

Although all courts have the power and the obligation to review the constitutionality of government action and legislation within their jurisdiction, only the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) in Karlsruhe may declare legislation unconstitutional. Other courts must suspend proceedings if they find a statute unconstitutional and must submit the question of constitutionality to the Federal Constitutional Court. In serious criminal cases the trial courts sit with lay judges, similar to jurors, who are chosen by lot from a predetermined list. The lay judges decide all questions of guilt and punishment jointly with the professional judges. Lay judges also participate in some noncriminal matters.

Judges on the Federal Constitutional Court are chosen for nonrenewable 12-year terms. The Bundestag and Bundesrat each select half of the court’s 16 judges; in each case, a nominee must win two-thirds support to secure appointment. The court sits in two eight-member Senates, which handle ordinary cases. Important cases are decided by the entire body.

Judges play a more prominent and active role in all stages of legal proceedings than do their common-law counterparts, and proceedings in German courts tend to be less controlled by prosecutors and defense attorneys. There is less emphasis on formal rules of evidence, which in the common-law countries is largely a by-product of the jury system, and more stress on letting the facts speak for what they may be worth in the individual case. There is no plea bargaining in criminal cases. In Germany, as in most European countries, litigation costs are relatively low compared with those in the United States, but the losing party in any case usually must pay the court costs and attorney fees of both parties.

Although codes and statutes are viewed as the primary source of law in Germany, precedent is of great importance in the interpretation of legal rules. German administrative law, for example, is case law in the same sense that there exists no codification of the principles relied upon in the process of reviewing administrative action. These principles are mostly the law as determined by previous judicial rulings. Germans see their system of judicial review of administrative actions as implementation of the rule of law. In this context an emphasis is placed on the availability of judicial remedies.

Unification brought about the integration and adaptation of the administration of justice of East and West Germany; however, this was complicated by the large number of judges who were incapacitated by the union. Many judges were dismissed either because they owed their appointment as judges primarily to their loyalty to the communist government or because of their records. To fill the many vacancies created in the courts of the new states, judges and judicial administrators were recruited from former West Germany. Indeed, a large number were “put on loan” from the western states and many others urged out of retirement to help during the transition.

Luftfahrt-Bundesamt (LBA)

By law of November 30, 1954 (Federal Law Gazette p. 354), the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt (LBA), the Federal Aviation Office, was established as the supreme Federal Authority to fulfill tasks in the field of civil aviation. It is subordinated to the Federal Minister of Transport and Digital Infrastructure (BMDV). The LBA consists of the Headquarters in Braunschweig and the Regional Offices in Düsseldorf, Frankfurt/Main, Hamburg, Munich, Stuttgart and Berlin. The tasks of the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt are laid down in the LBA Act (Gesetz über das Luftfahrt-Bundesamt). The most important goal of the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt is to avert hazards to the safety of aviation as well as to public safety and order. The origins of the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt can be traced back to the year of 1918. At that time, after the end of World War I, the “Reichsamt des Inneren” (national office of the interior) was provisionally charged to settle matters in aviation. Finally, the “Reichsluftamt” (national office of aviation) was given the responsibility for these tasks and in this way became the predecessor of the present Luftfahrt-Bundesamt. The first director of this Office was Undersecretary August Euler, a well-known pioneer in flying. In 1920, the Reichsverkehrsministerium (national ministry of transport) was founded. After the reorganization of aviation administration in 1933/34, all competencies were transferred to the Reichsluftministerium (RLM) (national ministry of aviation) and its subordinate offices.

After the end of World War II, aviation administration was taken over by the occupying powers. With the re-establishment of air sovereignty, the paths of aviation administration in Germany diverged for political reasons. The GDR (German Democratic Republic) went its own way and transferred civil aviation administration to the “Hauptverwaltung der Zivilen Luftfahrt im Ministerium für Verkehrswesen (HVZL) (head quarters of civil aviation administration at the ministry of transport) and the ”Staatliche Luftffahrt-Inspektion (SLI)“ (national aviation inspection).

In the Federal Republic of Germany, civil administration was assigned on the one hand to the Federal Government, i.e. to the “Bundesministerium für Verkehr (BMV)“ (German Federal Ministry of Transport) and on the other, to the Federal States (Laender) with their aeronautical authorities, thus dividing civil aviation administration between the Government and the Laender.

In 1954, the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt was founded to assist the BMV. The tasks to be fulfilled were assigned to the LBA by law. At the same time, Dr. Ing. Hans-Christoph Seebohm, the then Federal Minister of Transport and former President of the Chamber of Industry and Commerce in Braunschweig, nominated the city of Braunschweig to be the seat of the Office of Civil Aviation. One argument which he put forward in favor of Braunschweig and which showed his far-sightedness was the central location of the Authority in a re-united Germany.

With the tasks defined and location determined, the fundament was created, and, on February 1, 1955, the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt was able to start work with 28 staff members in the main building at Braunschweig airport.

In the course of time, as a result of increasing air traffic, higher requirements on safety, and finally the reunification of Germany, the LBA developed from its small beginnings to what it is today. With more than 100 certification, inspection and surveillance functions, the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt guarantees the high technical and operational standard of aviation in Germany.

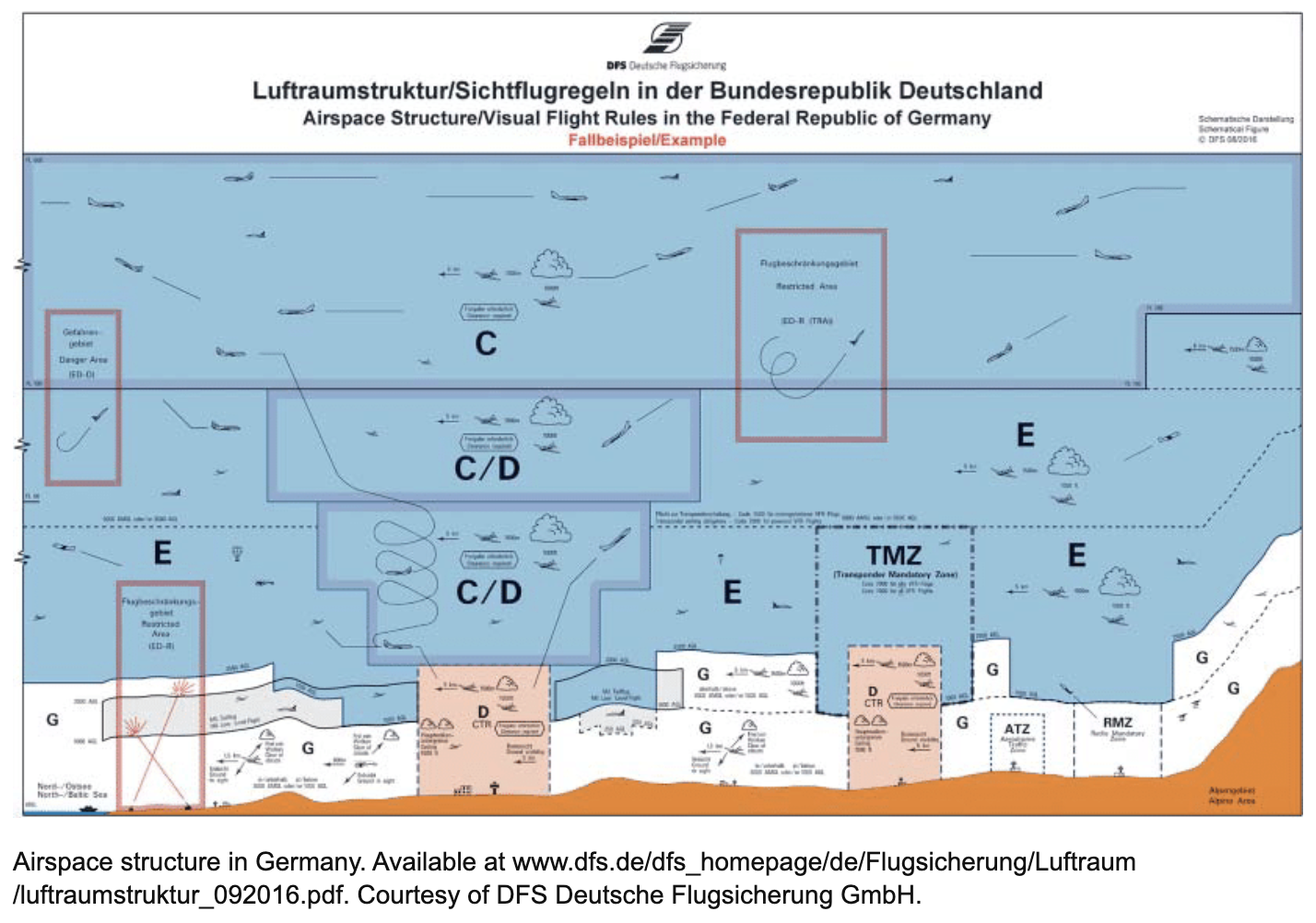

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

DFS

DFS – Deutsche Flugsicherung GmbH – is the German air navigation service provider

German air traffic and infrastructure map – digital platform for unmanned aviation

Drone Regulations

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

Bilateral agreements facilitate the reciprocal airworthiness certification of civil aeronautical products imported/exported between two signatory countries. A Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement (BAA) or Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement (BASA) with Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA) provides for airworthiness technical cooperation between the FAA and its counterpart civil aviation authorities.

Reciprocal acceptance of aviation safety-related approvals and services with the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and Member States of the European Union are primarily governed by the U.S. – European Union Safety Agreement.

Note: The European Union has designated that import, export, and oversight of certain ‘low risk’ civil aviation products are not covered by the EU, and will be administered by individual EU Member State aviation authorities. These products are defined in Annex 1 of REGULATION (EU) 2018/1139 (formerly known as “Annex 2 aircraft”). FAA validation/U.S. import of these products will be governed by the BASA IPA between the FAA and that EU Member State aviation authority, not the US-EU Safety Agreement.

Legacy Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA): Contact AIR-40 at 9-AWA-AVS-AIR400@faa.gov for assistance when using this legacy IPA in support of a project, and before contacting an Authority about use and effectivity of this document.

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

2025 – AAMG edges closer to buying Lilium eVTOL assets

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the July 2025 Global AAM Forum.

2025 – Volocopter, ADAC Luftrettung partner on eVTOL medical ops

2025 – German Airline Plans To Operate Hydrogen-electric Beech 1900s

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 1 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 2 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

2024 – Germany maps out timeline for electric air taxi operations

2024 – China’s Geely in talks for control of Volocopter

2024 – CityAirbus NextGen prototype completes first liftoff

2024 – Lilium begins integration testing of eVTOL aircraft power system

2024 – German Start-up ERC Unveils Emergency Medical eVTOL Aircraft

2024 – Lilium begins building eVTOL aircraft testing facility in Germany

2024 – Unifly’s UTM Platform Advances Urban Air Mobility in Europe

2024 – Global airport operator Fraport and Lilium to collaborate on development of commercial eVTOL network

2023 – Lilium completes EASA design organization audits for eVTOL aircraft program

2023 – Germany’s DLR To Build VTOL Crash And Impact Test Center

2023 – ADVANCED AIR MOBILITY FLIGHT TEST SITE TO OPEN AT GERMAN AIRPORT

2022 – Airbus leads advanced air mobility initiative in Germany

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film the castle in Bavaria, pictured above.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?