68 France

Three equal vertical bands of blue (hoist side), white, and red. Known as the “Le drapeau tricolore” (French Tricolor), the origin of the flag dates to 1790 and the French Revolution when the “ancient French color” of white was combined with the blue and red colors of the Parisian militia. The official flag for all French dependent areas.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

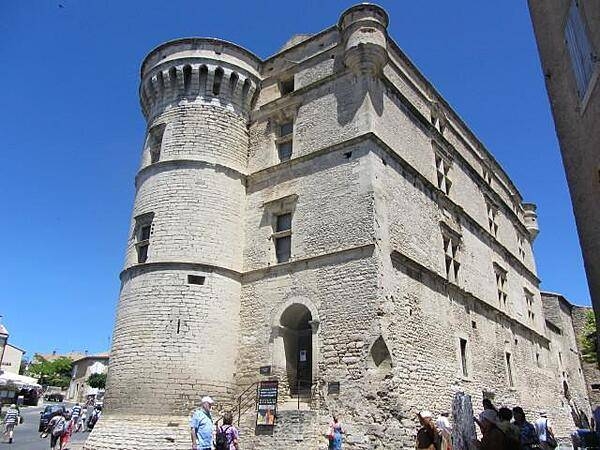

The Castle on the village square in Gordes, Provence, was partially rebuilt in 1525.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, when France fell into political turmoil after the May 1958 insurrection in Algeria (then still a French colony), General Charles de Gaulle, an outspoken critic of the postwar constitution who had served as the provisional head of government in the mid-1940s, returned to political life as prime minister. He formed a government and, through the constitutional law of June 1958, was granted responsibility for drafting a new constitution. With the assistance of Michel Debré, de Gaulle crafted the constitution of the Fifth Republic. The drafting of the constitution of the Fifth Republic and its promulgation on October 4, 1958, differed in three main ways from the former constitutions of 1875 (Third Republic) and 1946 (Fourth Republic): first, the parliament did not participate in its drafting, which was done by a government working party aided by a constitutional advisory committee and the Council of State; second, French overseas territories participated in the referendum that ratified it on September 28, 1958; and, third, initial acceptance was widespread, unlike the 1946 constitution, which on first draft was rejected by popular referendum and then in a revised form was only narrowly approved. In contrast, the 1958 constitution was contested by 85 percent of the electorate, of which 79 percent were in favor; among the overseas territories only Guinea rejected the new constitution and consequently withdrew from the French Community.

In order to achieve the political stability that was lacking in the Third and the Fourth Republic, the constitution of 1958 adopted a mixed (semi presidential) form of government, combining elements of both parliamentary and presidential systems. As a result, the parliament is a bicameral legislature composed of elected members of the National Assembly (lower house) and the Senate (upper house). The president is elected separately by direct universal suffrage and operates as head of state. The constitution gives the president the power to appoint the prime minister (often known as the premier), who oversees the execution of legislation. The president also appoints the Council of Ministers, or cabinet, which together with the prime minister is referred to as the government.

The French system is characterized by the strong role of the president of the republic. The office of the president is unique in that it has the authority to bypass the parliament by submitting referenda directly to the people and even to dissolve the parliament altogether. The president presides over the Council of Ministers and other high councils, signs the more important decrees, appoints high civil servants and judges, negotiates and ratifies treaties, and is commander in chief of the armed forces. Under exceptional circumstances, Article 16 allows for the concentration of all the powers of the state in the presidency. This article, enforced from April to September 1961 during the Algerian crisis, has received sharp criticism, having proved to be of limited practical value because of the stringent conditions attached to its operation.

De Gaulle’s great influence and the pressures of unstable political conditions tended to reinforce the authority of the presidency at the expense of the rest of the government. Whereas the constitution (Article 20) charges the government to “determine and direct” the policy of the nation, de Gaulle arrogated to himself the right to take the more important decisions, particularly concerning foreign, military, and institutional policies, and his successors adopted a similar pattern of behaviour. The constitution of 1958 called for a presidential term of seven years, but, in a referendum in 2000, the term was shortened to five years, beginning with the 2002 elections.

The role of the prime minister, however, has gradually gained in stature. Constitutionally, the office is responsible for the determination of governmental policy and exercises control over the civil service and the armed forces. Moreover, while all major decisions tended to be taken at the Élysée Palace (the residence of the president) under de Gaulle, responsibility for policy, at least in internal matters, has slowly passed to the head of the government. Especially since the mid-1970s, a working partnership between the president and the prime minister has tended to be established. Finally, the power of the president is tied to the parliamentary strength of the parties that support him and that form a majority in the National Assembly. It is possible, however, for the president’s parties to become a minority in the assembly, in which case the president must appoint a prime minister from the majority faction. Beginning in 1986, France experienced several periods of divided government, known as “cohabitation,” in which the president and the prime minister belonged to different parties.

The National Assembly is composed of 577 deputies who are directly elected for a term of five years in single member constituencies on the basis of a majority two-ballot system, which requires that a runoff take place if no candidate has obtained the absolute majority on the first ballot. The system was abandoned for proportional representation for the 1986 general election, but it was reintroduced for the 1988 election and has remained in place ever since. In 2012 the Senate was composed of 348 senators indirectly elected for six years by a collège électoral consisting mainly of municipal councillors in each département, one of the administrative units into which France is divided. The parliament retains its dual function of legislation and control over the executive but to a lesser extent than in the past. The domain of law (Article 34) is limited to determining the basic rules and fundamental principles concerning such matters as civil law, fiscal law, penal law, electoral law, civil liberties, labour laws, amnesty, and the budget. In these matters the parliament is sovereign, but the government can draw up the details for the application of laws.

The government is responsible for all other matters, according to Article 37 of the constitution, and the assemblies can in no way interfere; the Constitutional Council is responsible for ensuring that these provisions are respected. The parliament can temporarily delegate part of its legislative power to the government, which then legislates by ordinances. This procedure has been used on matters concerning Algeria, social security, natural disasters, European integration, and unemployment. Finally, government and the parliament are advised by an Economic and Social Council, composed of 230 representatives of various groups (e.g., trade unions and employers’ and farmers’ organizations) that must be consulted on long-term programs and on developments and that may be consulted on any bill concerning economic and social matters.

The right to initiate legislation is shared by the government and the parliament. Bills are studied by parliamentary committees, although the government does control the agenda. The government can also, at any point during the debate over a bill, call for a single vote on the whole of the bill’s text. Parliamentary control over the government can be exercised, but it is less intense than in the British system. There are questions to ministers challenging various aspects of performance, but these take place infrequently and are primarily occasions for lesser debates and do not lead to effective scrutiny of the government’s practices. Committee inquiries are also relatively rare. The National Assembly, however, has the right to censure the government, but, in order to avoid the excesses that occurred before 1958 (as a result of which governments often fell once or twice a year), the motion of censure is subject to considerable restrictions. Only once in the first 50 years of the Fifth Republic, in 1962, did the National Assembly pass a motion of censure, when it stalled de Gaulle’s referendum for direct election of the president by universal suffrage, which ultimately met with approval. The government is also strengthened by its constitutional power to ask for a vote of confidence on its general policy or on a bill. In the latter case a bill is considered adopted unless a motion of censure has obtained an absolute majority.

The people may be asked to ratify, by a constituent referendum (Article 89), an amendment already passed by the two houses of the parliament. The constitution made provision for legislative referenda, by which the president of the republic has the authority to submit a proposed bill to the people relating to the general organization of the state (Article 11).

This procedure was used twice in settling the Algerian question of independence, first in January 1961, to approve self-determination in Algeria (when 75 percent voted in favor), and again in April 1962, approving the Évian Agreement, which gave Algeria its independence from France (when 91 percent voted in favor). The use of this latter procedure to amend the constitution without going through the preliminary phase of obtaining parliamentary approval is constitutionally questionable, but it led to a significant result when, in October 1962, the election of the president by universal suffrage was approved by 62 percent of those voting. In April 1969, however, in a referendum concerning the transformation of the Senate into an economic and social council and the reform of the regional structure of France, fewer than half voted in favour, and this brought about President de Gaulle’s resignation.

Through the end of the 20th century, national referenda were met with low voter turnout. The procedure was used in 1972 for the enlargement of the European Economic Community (EEC) by the proposed addition of Denmark, Ireland, Norway, and the United Kingdom; in 1988 for the proposed future status of the overseas territory of New Caledonia; and in 1992 for approval of the Maastricht Treaty, which established the European Union. In 1995, when minor modifications were made to the constitution, the use of the referendum was enlarged to include proposed legislation relating to the country’s economic and social life. In 2000 a referendum shortened the presidential term from seven to five years. A 2005 referendum on a proposed constitution for the European Union was soundly defeated, and the setback forced EU officials to consider alternative means to further European integration.

The Constitutional Council is appointed for nine years and is composed of nine members, three each appointed by the president, the National Assembly, and the Senate. It supervises the conduct of parliamentary and presidential elections, and it examines the constitutionality of organic laws (those fundamentally affecting the government) and rules of parliamentary procedure. The council is also consulted on international agreements, on disputes between the government and the parliament, and, above all, on the constitutionality of legislation. This power has increased over the years, and the council has been given a position comparable to that of the U.S. Supreme Court.

The main units of local government, defined by the constitution as collectivités territoriales (“territorial collectivities”), are the régions, the départements, the communes, and the overseas territories. A small number of local governments, known as collectivités territoriales à statut particulier (“territorial collectivities with special status”), have slightly different administrative frameworks; among these are the island of Corsica and the large cities of Paris, Lyon, and Marseille.

One of the main features of decentralization in French government has evolved through the creation of the régions. These include the 21 metropolitan régions of mainland France as well as the 5 overseas regions of Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, Mayotte, and Réunion. (The overseas régions are simultaneously administered as overseas départements.) Although Corsica is still commonly described as one of 22 régions of metropolitan France, its official status was changed in 1991 from région to collectivité territoriale à statut particulier; its classification, unique among France’s local governments, provides Corsica greater autonomy than the régions.

After a number of limited changes lasting two decades, a 1982 law set up directly elected regional councils with the power to elect their executive. The law also devolved to the regional authorities many functions hitherto belonging to the central government, in particular economic and social development, regional planning, education, and cultural matters. The régions have gradually come to play a larger part in the administrative and political life of the country.

The région to an extent competes with the département, which was set up in 1790 and is still regarded by some as the main intermediate level of government. With the creation in 1964 of new départements in the Paris region and the dividing in two of Corsica in 1976, the number of départements reached 100: 96 in metropolitan France and 4 overseas (Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, and Réunion, which are simultaneously administered as régions). In 2009, residents of Mayotte voted overwhelmingly in favor of département status, and two years later it became France’s fifth overseas (and its 101st total) département. Each département is run by the General Council, which is elected for six years with one councillor per canton. There are between 13 and 70 cantons per département. The General Council is responsible for all the main departmental services: welfare, health, administration, and departmental employment. It also has responsibility for local regulations, manages public and private property, and votes on the local budget.

A law passed in 1982 enhanced decentralization by increasing the powers and authority of the départements. Formerly, the chief executive of the département was the government-appointed prefect (préfet), who also had strong powers over other local authorities. Since the law went into effect, however, the president of the General Council is the chief executive and the prefect is responsible only for preventing the actions of local authorities from going against national legislation.

The commune, the smallest unit of democracy in France, dates to the parishes of the ancient régime in the years before the Revolution. Its modern structure dates from a law of 1884, which stipulates that communes have municipal councils that are to be elected for six years, include at least nine members, and be responsible for “the affairs of the commune.” The council administers public land, sets up public undertakings, votes on its own budget, and over recent years has played an increasing role in promoting local economic development. It elects a mayor and the mayor’s assistants. Supervision by the central government, once very tight, has been markedly reduced, especially since 1982.

The mayor is both the chief executive of the municipal council and the representative of the central government in the commune. The mayor is in charge of the municipal police and through them ensures public order, security, and health and guarantees the supervision of public places to prevent such things as fires, floods, and epidemics. The mayor also directs municipal employees, implements the budget, and is responsible for the registry office. French mayors are usually strong and often dominate the life of the commune. They are indeed important figures in the political life of the country.

French communes are typically quite small; there are more than 36,500 of them. Efforts have been made to group communes or to bring them closer to one another, but these have been only partly successful. In certain cities, such as Lyon and Lille, cooperative urban communities have been created to enable the joint management and planning of a range of municipal services, among them waste disposal, street cleaning, road building, and fire fighting. A similar approach has been adopted elsewhere, including rural areas, with the establishment of syndicats intercommunaux that allows services to be administered jointly by several communes. Moreover, since the 1999 law on Regional Planning and Sustainable Development, the communes within urban areas of more than 50,000 inhabitants have been encouraged to pool resources and responsibilities to promote joint development projects by means of a new form of administrative unit known as the communauté d’agglomération.

The status of many of France’s overseas territories—vestiges of the French Empire—changed in the 1970s. Independence was proclaimed in 1975 by the Indian Ocean archipelago of the Comoros, with the exception of Mayotte (Mahoré) island, which chose to remain within French rule; in 1977 by Djibouti, on the Horn of Africa; and in 1980 by the Anglo-French Pacific Ocean condominium of the New Hebrides, under the name of Vanuatu. Mayotte was elevated to the status of territorial collectivity in 1976, and in North America the island territory of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon was elevated to the same status in 1985. France granted Mayotte, known as a departmental collectivity from 2001, the status of overseas département in 2011.

The only places retaining overseas territory status are French Polynesia (with its capital at Papeete on the island of Tahiti), New Caledonia, the Wallis and Futuna islands in the Pacific, and the Adélie Land claim in Antarctica. These territories have substantial autonomy except in matters reserved for metropolitan France, such as diplomacy and defense. They are governed through various but similar administrative structures, usually involving an elected council and a chief executive, but they are subject to the tutelage of a representative of the French Republic. A 1998 decision regarding New Caledonia envisaged the progressive transfer of political responsibilities to the island over a period of 15 to 20 years.

In France there are two types of jurisdictions: the judiciary that judges trials between private persons and punishes infringements of the penal law and an administrative judicial system that is responsible for settling lawsuits between public bodies, such as the state, local bodies, and public establishments, as well as private individuals.

For civil cases the judiciary consists of higher courts (grande instance) and lower courts (tribunaux d’instance), which replaced justices of the peace in 1958. For criminal cases there are tribunaux correctionnels (“courts of correction”) and tribunaux de police, or “police courts,” which try minor offenses. The decisions of these courts can be referred to one of the 35 courts of appeal. Felonies are brought before the assize courts established in each département, consisting of three judges and nine jurors.

All these courts are subject to the control of the Court of Cassation, as are the specialized professional courts, such as courts for industrial conciliation, courts-martial, and, from 1963 to 1981, the Court of State Security, which tried felonies and misdemeanors against national security. Very exceptionally, in cases of high treason, a High Court of Justice (Cour de Justice de la République), composed of members of the National Assembly and of senators, is empowered to try the president of the republic and the ministers. They can also be tried by this court if they have committed felonies or misdemeanors during their term of office. These are the only situations in which the Court of Cassation is not competent to review the case. Otherwise, the court examines judgments in order to assess whether the law has been correctly interpreted; if it finds that this is not the case, it refers the case back to a lower court.

The more than 5,000 judges are recruited by means of competitive examinations held by the National School of the Magistracy, which was founded in 1958 and in 1970 replaced the National Centre for Judicial Studies. A traditional distinction is made between the magistrats du siège, who try cases, and the magistrats de parquet (public prosecutors), who prosecute. Only the former enjoy the constitutional guarantee of irremovability. The High Council of the Judiciary is made up of 20 members originally appointed by the head of state from among the judiciary. Since 1993, however, its members have been elected, following reforms designed to free the judiciary from political control. The Council makes proposals and gives its opinion on the nomination of the magistrats du siège. It also acts as a disciplinary council. Public prosecutors act on behalf of the state. They are hierarchically subject to the authority of the minister of justice. Judges can serve successively as members of the bench (siège) and the public prosecutor’s department. They act in collaboration with, but are hierarchically independent of, the police.

One of the special characteristics of the French judicial system is the existence of a hierarchy of administrative courts whose origins date to Napoleon. The duality of the judicial system has been sometimes regarded unfavorably, but the system has come to be gradually admired and indeed widely adopted in continental European countries and in the former French colonies. The administrative courts are under the control of the Council of State, which examines cases on appeal. The Council of State thus plays a crucial part in exercising control over the government and the administration from a jurisdictional point of view and ensures that they conform with the law. It is, moreover, empowered by the constitution to give its opinion on proposed bills and on certain decrees.

French Civil Aviation Authority (DGAC)

The DGAC, the French Civil Aviation Authority, is responsible for ensuring the safety and the security of French air transport, as well as maintaining a balance between the development of the air transport sector and environmental protection. It is the national regulatory authority, but it also provides safety oversight, air navigation services and training. He is a partner of key players in the aeronautical industry and he is also in charge of financial aid for research in aircraft construction and state industrial policy in this sector.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

U-Space – digital drone air traffic management

Drone Regulations

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

DGAC published the updated version of UAS in the specific category, and included UAM.

Bilateral agreements facilitate the reciprocal airworthiness certification of civil aeronautical products imported/exported between two signatory countries. A Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement (BAA) or Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement (BASA) with Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA) provides for airworthiness technical cooperation between the FAA and its counterpart civil aviation authorities.

Reciprocal acceptance of aviation safety-related approvals and services with the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and Member States of the European Union are primarily governed by the U.S. – European Union Safety Agreement.

Note: The European Union has designated that import, export, and oversight of certain ‘low risk’ civil aviation products are not covered by the EU, and will be administered by individual EU Member State aviation authorities. These products are defined in Annex 1 of REGULATION (EU) 2018/1139 (formerly known as “Annex 2 aircraft”). FAA validation/U.S. import of these products will be governed by the BASA IPA between the FAA and that EU Member State aviation authority, not the US-EU Safety Agreement.

Legacy Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA): Contact AIR-40 at 9-AWA-AVS-AIR400@faa.gov for assistance when using this legacy IPA in support of a project, and before contacting an Authority about use and effectivity of these documents.

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

2025 – Blue Spirit Aero Makes Case for Dragonfly Family of Hydrogen-powered Aircraft

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the July 2025 Global AAM Forum.

2025 – Ascendance advances VTOL prototype assembly

2025 – Ascendance, Airbus partner on hybrid-electric technology

2025 – Volocopter Partners with Jet Systems to Launch eVTOL Services in France

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 1 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 2 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

2024 – Volocopter misses Paris Olympics debut

2024 – Volocopter completes eVTOL test at France’s Palace of Versailles

2024 – Volocopter Flies eVTOL Aircraft Validation Mission in Paris

2024 – Volocopter conducts crewed eVTOL test flight in France

2024 – Paris scraps plans for Olympic ‘flying taxis’

2024 – Lilium, UrbanV to launch eVTOL service in southern France

2024 – Unifly’s UTM Platform Advances Urban Air Mobility in Europe

2023 – Volocopter’s Christian Bauer on starting commercial eVTOL flights during 2024 Paris Olympics

2023 – Lilium, UrbanV to develop AAM infrastructure in Italy, France

2023 – eVTOLs Expected to Take Center Stage at Paris 2024 Olympic Games

2022 – Air Mobility Testbed in France Launched: Open for UAM Ecosystem

2022 – Urban air mobility flight tests in France a success

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film over Provence, pictured above.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?