134 China

Red with a large yellow five-pointed star and four smaller yellow five-pointed stars (arranged in a vertical arc toward the middle of the flag) in the upper hoist-side corner. The color red represents revolution, while the stars symbolize the four social classes – the working class, the peasantry, the urban petty bourgeoisie, and the national bourgeoisie (capitalists) – united under the Communist Party of China.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

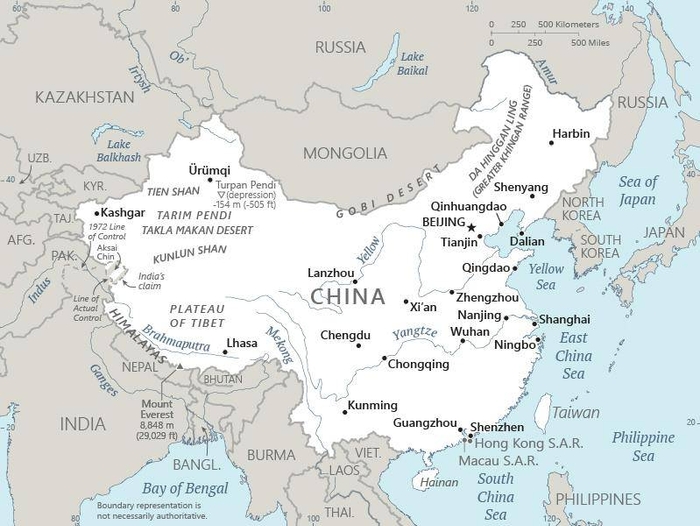

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

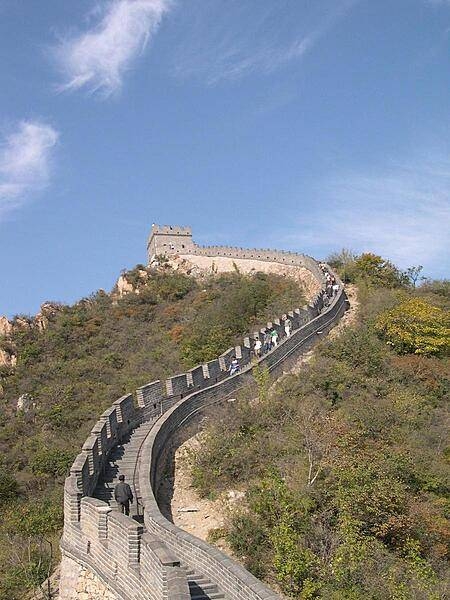

A crenellated walkway on top of the Great Wall. The Wall stretched for many thousands of miles linking fortresses. Signal towers were used for communication.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, despite its size, the People’s Republic of China is organized along unitary rather than federal principles. Both the government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP; Pinyin: Zhongguo Gongchan Dang; Wade-Giles romanization: Chung-kuo Kung-ch’an Tang), moreover, operate “from the top down,” arrogating to the “Centre” all powers that are not explicitly delegated to lower levels. To run the country, the government and the CCP have established roughly parallel national bureaucracies extending from Beijing down to local levels. These bureaucracies are assisted by various “mass organizations”, e.g., trade unions, a youth league, women’s associations, and writers’ and other professional associations, that encompass key sectors of the population. These organizations, with their extremely large memberships, have generally served as transmission lines for communicating and uniformly implementing policies affecting their members. No voluntary associations are permitted to function that are wholly independent of CCP and government leadership.

The CCP and government bureaucracies themselves are organized along territorial and functional lines. The territorial organization is based on a number of administrative divisions, with both a CCP committee and a “people’s government” in charge of each. These territorial divisions include the national level in Beijing (the Centre), 33 provincial-level units (4 directly administered cities, 5 autonomous regions, the Hong Kong and Macau special administrative regions, and 22 provinces, excluding Taiwan), some 330 prefectural bodies, more than 2,850 county-level entities, and numerous cities, towns, and townships. Some larger cities are themselves divided into urban wards and counties. This territorial basis of organization is intended to coordinate and lend coherence to the myriad policies from the Centre that may affect any given locale.

The functionally based political organization is led on the government side by ministries and commissions under the State Council and on the CCP side by Central Committee departments. These central-level functional bodies sit atop hierarchies of subordinate units that have responsibility for the sector or issue area under concern. Subordinate functional units typically are attached to each of the territorial bodies.

This complex structure is designed to coordinate national policy (such as that toward the metallurgical industry), assure some coordination of policy on a territorial basis, and enable the CCP to keep control over the government at all levels of the national hierarchy. One unintended result of this organizational approach is that China employs more than 10 million officials, a number that exceeds the populations of many of the world’s countries.

There are tensions among these different goals, and thus a great deal of shifting has occurred since 1949. During the early and mid-1950s the government’s functional ministries and commissions at the Centre were especially powerful. The Great Leap Forward, starting in 1958, shifted authority toward the provincial- and lower-level territorial CCP bodies. During the Cultural Revolution, starting in 1966, much of the political system became so disrupted that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was called in and assumed control. When the PLA fell under a political cloud, the situation became remarkably fluid and confused for much of the 1970s.

Since then the general thrust has been toward less-detailed CCP supervision of the government and greater decentralization of government authority where possible. But the division of authority between CCP and government and between territorial and functional bodies has remained in a state of flux, as demonstrated by a trend again toward centralization at the end of the 1980s and subsequent efforts toward decentralization since the late 1990s. The Chinese communist political system still has not become institutionalized enough for the distribution of power among important bodies to be fixed and predictable.

The fourth constitution of the People’s Republic of China was adopted in 1982. It vests all national legislative power in the hands of the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee. The State Council and its Standing Committee, by contrast, are made responsible for executing rather than enacting the laws. This basic division of power is also specified for each of the territorial divisions, province, county, and so forth, with the proviso in each instance that the latitude available to authorities is limited to that specified by law.

All citizens 18 years of age and older who have not been deprived of their political rights are permitted to vote, and direct popular suffrage is used to choose People’s Congress members up to the county level. Above the counties, delegates at each level elect those who will serve at the People’s Congress of the next higher level. Were this constitution an accurate reflection of the real workings of the system, the People’s Congresses and their various committees would be critical organs in the Chinese political system. In reality, though, they are not.

Actual decision-making authority in China resides in the state’s executive organs and in the CCP. At the national level the top government executive organ is the State Council, which is led by the premier. The constitution permits the appointment of vice-premiers, a secretary-general, and an unspecified number of councillors of state and heads of ministries and commissions. The premier, vice-premiers, state councillors, and secretary-general meet regularly as the Standing Committee, in which the premier has the final decision-making power. This Standing Committee of the State Council exercises major day-to-day decision-making authority, and its decisions de facto have the force of law.

While it is not so stipulated in the constitution, each vice-premier and councillor assumes responsibility for the work of one or more given sectors or issues, such as education, energy policy, or foreign affairs. The leader concerned then remains in contact with the ministries and the commissions of the State Council that implement policy in that area. This division of responsibility permits a relatively small body such as the Standing Committee of the State Council (consisting of fewer than 20 people) to monitor and guide the work of a vast array of major bureaucratic entities. When necessary, of course, the Standing Committee may call directly on additional expertise in its deliberations. The National People’s Congress meets roughly annually and does only a little more than to ratify the decisions already made by the State Council.

Parallel to the State Council system is the central leadership of the CCP. The distribution of power among the various organs at the top of the CCP, the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau (Politburo), the Political Bureau itself, and the Secretariat, has varied a great deal, and from 1966 until the late 1970s the Secretariat did not function at all. There is in any case a partial overlap of membership among these organs and between these top CCP bodies and the Standing Committee of the State Council. In addition, formally retired elder members of the party have often exercised decisive influence on CCP decision making.

According to the CCP constitution of 1982, the National Party Congress is the highest decision-making body. Since the Party Congress typically convenes only once in five years, the Central Committee is empowered to act when the Congress is not in session. Further, the Political Bureau can act in the name of the Central Committee when the latter is not in session, and the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau guides the work of the Political Bureau. The Secretariat is charged with the daily work of the Central Committee and the Political Bureau. The general secretary of the party presides over the Secretariat and also is responsible for convening the meetings of the Political Bureau and its Standing Committee. The Secretariat works when necessary through several departments (the department for organization, for example, or the department for propaganda) under the Central Committee.

Until 1982 the CCP had a chairmanship that was unique among ruling communist parties. Mao Zedong held this office until his death in 1976, and Hua Guofeng was chairman until his removal from office in 1981. Hu Yaobang then served as party chairman until the post was abolished in 1982. The decision to redefine the position was part of the effort to reduce the chances of any one leader’s again rising to a position above the party, as Mao had done. China’s government still has a chairmanship, but the office has only limited power and is largely ceremonial.

The division of power among the leading CCP organs and between them and the State Council is constantly shifting. The Standing Committee of the Political Bureau and the Political Bureau as a whole have the authority to decide on any issue they wish to take up. The Secretariat has also at times played an extremely powerful and active role, meeting more frequently than either the Political Bureau or its Standing Committee and making many important decisions on its own authority. Similarly, the State Council has made many important decisions, but its power is always exercised at the pleasure of the CCP leadership.

Since the late 1970s China has taken a number of initiatives to move toward a more institutionalized system in which the office basically determines the power of its incumbent rather than vice versa, as has often been the case. Thus, for example, the CCP and state constitutions adopted in 1982 (and subsequently amended somewhat) for the first time stipulated a number of positions that confer membership status on the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau. These positions are the head of the Party Military Affairs Commission, the general secretary of the CCP, the head of the Central Advisory Committee, and the head of the Central Discipline Commission. In addition, for the first time under the stipulations of the constitution, limits of two consecutive terms were placed on the government offices of premier, vice-premier, and state councillor. There were no similar constitutional restrictions on the tenure of incumbents to top CCP positions.

In theory, the CCP sets major policy directions and broadly supervises the implementation of policy to ensure that its will is not thwarted by the state and military bureaucracies. The CCP also assumes major responsibility for instilling proper values in the populace. The government, according to the theory, is responsible for carrying out CCP policy, making the necessary decisions as matters arise. Of course, this clear division of labour quickly becomes blurred for a number of reasons. For example, only since the late 1970s has a concerted effort been made to appoint different people to the key executive positions in the CCP and the government. Prior to that time, the same individual would head both the CCP committee and the government body in charge of any given area. At the highest levels the premier of the government and the chairman of the party continue to sit on the CCP Political Bureau.

More fundamentally, it is often impossible to clearly separate policy formation and implementation in a huge, complex set of organizations charged with a multiplicity of tasks. The tendency has been for CCP cadres to become increasingly involved in day-to-day operations of the government, until some major initiative was taken by the top national leadership to reverse the trend. While the distinction between the CCP and the government is of considerable significance, therefore, the ruling structure in China can also be viewed from the functional point of view mentioned above. The careers of individual officials may shift among posts in both the CCP and the government, but for most officials all posts are held within one area of concern, such as economics, organization or personnel, security, propaganda, or culture.

A hierarchy of organization and personnel has been embedded in virtually all CCP and government bodies. Even on the government side, all officials in these personnel departments are members of the CCP, and they follow rules and regulations that are not subject to control by the particular bodies of which they are formally a part. This system has been used to assure higher-level CCP control over the appointments to all key positions in the CCP, government, and other major organizations (enterprises, universities, and so forth).

For much of the period between 1958 and 1978, these personnel departments applied primarily political criteria in making appointments. They systematically discriminated against intellectuals, specialists, and those with any ties or prior experience abroad. From 1978 to 1989, however, official policy was largely the reverse, with ties abroad being valued because of China’s stress on “opening the door” to the international community. A good education became an important asset in promoting careers, while a history of political activism counted for less or could even hinder upward mobility. A partial reversion to pre-1978 criteria was decreed in 1989, followed by periods of shifting between the two policies.

Two important initiatives have been taken to reduce the scope of the personnel bureaucracies. First, during 1984 the leaders of various CCP and government bodies acquired far greater power to appoint their own staffs and to promote from among their staffs on their own initiative. The leaders themselves still must be appointed via the personnel system, but most others are no longer fully subject to those dictates. Second, a free labour market has been encouraged for intellectuals and individuals with specialized skills, a policy that could further reduce the power of the personnel bodies.

The legal apparatus that existed before the changes made during the Cultural Revolution was resurrected in 1980. The State Council again has a Ministry of Justice, and procuratorial organs and a court system were reestablished. The legal framework for this system was provided through the adoption of various laws and legal codes. One significant difference was that for the first time the law provided that there should be no discrimination among defendants based on their class origin. China also reestablished a system of lawyers.

The actual functioning of this legal apparatus, however, has continued to be adversely affected by a shortage of qualified personnel and by deeply ingrained perspectives that do not accord the law priority over the desires of political leaders. Thus, for example, when the top CCP leadership ordered a severe crackdown on criminal activity in 1983, thousands were arrested and executed without fully meeting the requirements of the newly passed law on criminal procedures. That law was subsequently amended to conform more closely with the actual practices adopted during the crackdown. Subsequently, similar campaigns have been mounted against criminal activity.

Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC)

The Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) is the Chinese civil aviation authority under the Ministry of Transport. It oversees civil aviation and investigates aviation accidents and incidents. As the aviation authority responsible for China, it concludes civil aviation agreements with other aviation authorities, including those of the Special administrative regions of China which are categorized as “special domestic.” It directly operated its own airline, China’s aviation monopoly, until 1988. The agency is headquartered in Dongcheng District, Beijing. The CAAC does not share the responsibility of managing China’s airspace with the Central Military Commission under the regulations in the Civil Aviation Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

Drone Regulations

Regulations on Real-name Registration of Civil Unmanned Aircraft Systems

CAAC Issues Measures for the Management of Unmanned Civil Aviation Experimental Bases (Test Areas) – 2021

Civil Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Operation Safety Management Rules

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

CCAR Part 21, the Regulations on Conformity Certification of Civil Aviation Products and Parts, is the primary regulatory framework for airworthiness certification of civil aviation products and parts in China, overseen by the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC). It covers type qualification, production license, and airworthiness qualification certification for all civil aviation products and parts.

China Part 39, part of the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC), focuses on the transport of dangerous goods by air. Specifically, Article 39 mandates that operators provide readily accessible, translated Dangerous Goods Air Transport Manuals to relevant personnel (flight crew and others). This ensures they have the necessary information for safe handling of dangerous goods during air transport.

CCAR Part 145 – maintenance of aircraft

2020 – New safety regulators’ agreement moves China and EU closer together on UTM and UAM

2023 – China accepts first type certification application for piloted eVTOL

2023 – China publishes new rules on drone operations management and UTM

2024 – China plans to open airspace zones for drones, electric aircraft

2024 – CAAC Production Certificate Secured by EHang for the EH216-S

2024 – Interim Regulations on Unmanned Aircraft Flight Management

Bilateral agreements facilitate the reciprocal airworthiness certification of civil aeronautical products imported/exported between two signatory countries. A Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement (BAA) or Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement (BASA) with Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA) provides for airworthiness technical cooperation between the FAA and its counterpart civil aviation authorities.

Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement

Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness

2016 Notification of Policy Deviation Memorandum for FAA Order 8130.21H

Obtaining Certification Approval from this Country

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

2025 – AutoFlight introduces zero-carbon water vertiport

2025 – TCab Tech secures US$42M to boost E20 eVTOL global launch

2025 – The Great Chinese eVTOL Revolution

2025 – Chinese eVTOL aircraft start-ups gain momentum

2025 – Insufficient spacing cited in eVTOL accident in China

2025 – China’s low-altitude economy aims sky-high

2025 – EHang to establish VT35 hub in Hefei

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the July 2025 Global AAM Forum.

2025 – China’s AutoFlight Delivers First CarryAll eVTOL Freighter

2025 – AutoFlight’s CarryAll assists emergency groups at festival

2025 – AutoFlight gains Chinese AC for heavy-lift eVTOL aircraft

2025 – China’s TCab Technology wins US$1B order from UAE’s Autocraft for 350 E20 eVTOL aircraft

2025 – EHang Signs Pact With Chinese GA Service Provider

2025 – Jingyue orders 41 eVTOL aircraft from EHang

2025 – EHang, ANRA to partner on UAM in Europe, Latin America

2025 – EHang plans eVTOL commercial services in Guangzhou, Hefei

2025 – China’s EHang Says U.S. Tariffs Will Not Affect eVTOL Business

2025 – AutoFlight starts building eVTOL aircraft facility in China

2025 – EHang Earns World’s First eVTOL Air Operator Certificate

2025 – China’s TCab Tech raises more funding for eVTOL aircraft

2025 – China certifies first unmanned helicopter

2025 – EHang, JAC Motors, Guoxian to build eVTOL aircraft plant in China

2025 – China’s Low-Altitude Economy Builds Path for eVTOL Air Taxi Services

2025 – AutoFlight secures $21.5M deal for 12 large-scale electric aircraft

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 3 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

2024 – China Could Have 100,000 Flying Cars and Air Taxis Over Its Cities by 2030

2024 – EHang launches UAM hub at Luogang Central Park in China

2024 – Reports: China’s United Aircraft rolls out 6-ton tiltrotor UAV

2024 – Consultant: Costs, momentum favor AAM development in China

2024 – AutoFlight eVTOL aircraft conducts flight across Chang Jiang

2024 – EHang and China Southern Airlines General Aviation forge strategic partnership

2024 – New China FBO Looks To Meld Bizjets and AAM

2024 – Lilium, Bao’an District to establish China eVTOL hub

2024 – Xishan Tourism orders 50 EH216-S aircraft from China’s EHang

2023 – CITIC Offshore Helicopter and Lilium partner to launch eVTOL Network in China’s Greater Bay Area

2023 – China’s EHang Earns World’s First eVTOL Type Certificate

2023 – SHENZHEN’S BAO’AN DISTRICT BIDS TO BECOME ADVANCED AIR MOBILITY HUB IN CHINA

2023 – EHang and Shenzhen Bao’an District Form Strategic Partnership for eVTOL Operation

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film parts of the Great Wall, in the area of Beijing, pictured above.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?