155 Myanmar

Design consists of three equal horizontal stripes of yellow (top), green, and red. Centered on the green band is a large white five-pointed star that partially overlaps onto the adjacent colored stripes. The design revives the triband colors used by Burma from 1943-45, during the Japanese occupation.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

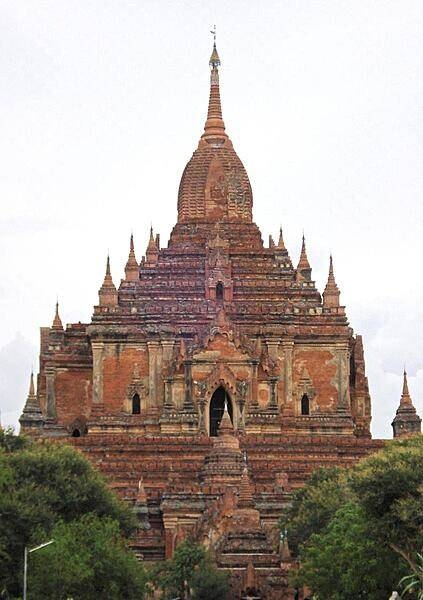

Htilominlo Temple in Bagan was completed around A.D. 1218 during the reign of King Nantaungmya; it is reputed to be the location where this king was chosen as crown prince. The three-story temple rises to 46 m (150 ft) and is built of red brick.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Last updated on March 22, 2025

Government

According to Britannica, Myanmar’s first constitution came into force on Jan. 4, 1974, the 26th anniversary of the country’s independence, and was suspended following a military coup on Sept. 18, 1988. The country was subsequently ruled by a military junta, known first as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) and, between 1997 and 2011, as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

Under the 1974 constitution, supreme power rested with the unicameral People’s Assembly (Pyithu Hluttaw), a 485-member popularly elected body that exercised legislative, executive, and judicial authority. The Council of State, which consisted of 29 members (one representative elected from each of the country’s 14 states and divisions, 14 members elected by the People’s Assembly as a whole, and the prime minister as an ex officio member), elected its own secretary and its own chairman, who was ex officio president of the country. The secretary and the president were also, respectively, the secretary-general and the chairman of the Burma Socialist Program Party (BSPP), which, under military leadership, was the only official political party from 1964 to 1988. Civil servants, members of the armed forces, workers, and peasants belonged to the BSPP, and senior military officials and civil servants were included in the party’s hierarchy.

After the military took control of the government in 1988, it established the SLORC as the new ruling body, and all state organs, including the People’s Assembly and the Council of State, were abolished and their duties assumed by the SLORC. The law designating the BSPP as the only political party also was abolished, and new parties were encouraged to register for general elections to a new legislative assembly. More than 90 parties participated in the elections, which were held in May 1990; of these the most important were the dominant BSPP, which had changed its name to the National Unity Party (NUP), and the main opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD).

The NLD won some four-fifths of the seats in the new assembly. However, after the NLD’s victory the SLORC announced that the elections were not actually for a legislative assembly but for a constituent assembly charged with drafting a new constitution; furthermore, the SLORC did not permit the assembly to meet. Instead, in 1993 the SLORC convened a National Convention of handpicked participants—rather than the elected assembly of 1990—to formulate a new constitution. This constituent assembly met intermittently in 1993–96 and then again from 2004 until early in 2008, when it finally passed a completed draft constitution. The constitution was put to a popular referendum in May and was approved, but the document did not to go into effect until Jan. 31, 2011, following elections for a new parliament that were held in November 2010.

Under the 2008 constitution, legislative authority is vested in a bicameral Assembly of the Union (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw) consisting of a 224-seat House of Nationalities (Amyotha Hluttaw) and a 440-seat House of Representatives (Pyithu Hluttaw).Three-fourths of the members of each chamber are directly elected, and the remaining one-fourth are appointed by the military; all members serve five-year terms. Executive authority, per the constitution, rests with the president, who is elected to a five-year term by members of the House of Representatives and heads an 11-member National Defense and Security Council (cabinet). However, it is thought that the military retained some level of influence on the government behind the scenes after Jan. 31, 2011.

In February 2021 the military seized power by detaining the president, upon which one of the vice presidents, a former military officer, became acting president and immediately invoked articles 417 and 418 of the constitution: the former allowing him to declare a one-year state of emergency and the latter allowing him to transfer power to the commander in chief of the armed forces. The legislative houses were also suspended per article 418. The State Administrative Council, headed by the commander in chief of the armed forces, was formed to handle the functions of government during the state of emergency.

Myanmar is divided administratively into seven states largely on the basis of ethnicity, Chin, Kachin, Kayin (Karen), Kayah, Mon, Rakhine (Arakan), and Shan, and seven more truly administrative divisions of Myanmar proper, Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy), Magway (Magwe), Mandalay, Bago (Pegu), Sagaing, Taninthary (Tenasserim), and Yangon. These states and divisions are subdivided further into townships, urban wards, and village tracts.

Until 1988, at each level of local government there was a People’s Council that followed the pattern of the People’s Assembly. Every local government council also had an Executive Committee, and all but the village or ward councils had a Committee of Inspectors. Local and national elections were held simultaneously. In 1988 the SLORC dissolved these bodies and assumed control of local administration, establishing in their place military-dominated Law and Order Restoration Councils.

The highest court under the 1974 constitution was the Council of People’s Justices, members of which were drawn from the People’s Assembly. Every local government council had a Judges’ Committee, which sat as the local court, exercising criminal and civil jurisdiction. These courts were abolished along with other government bodies following the coup of 1988, and a nonindependent Supreme Court was established as the central judicial authority, with justices appointed by the SLORC. Since that time, the judiciary has remained bound to the executive branch of government. The 2008 constitution has provisions for the creation of a Constitutional Tribunal of the Union to adjudicate constitutional cases.

Department of Civil Aviation (DCA)

The Department of Civil Aviation (DCA) is headed by the Director General (DG) and is a subordinate organization under the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MOTC), the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. The DCA is one of 9 departments and 2 institutes under the Ministry of Transport established by Executive Section of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Constitution of 2008. The DG is empowered by the Myanmar Aircraft Act 1934 and Myanmar Aircraft Rules 1937 generally for regulating Civil Aviation Activities in Myanmar. The DG, being the head of the DCA, is authorized by the President and Minister for Transport and Communications for the purpose. The DG may further delegate the powers vested in him to other DCA officers to fulfill the obligations for effective safety oversight.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

Drone Regulations

RESTRICTION OF DRONE OPERATIONS

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

None found by the author.

However, should you, the reader, happen to stumble across something to the contrary, please email the author at FISHE5CA@erau.edu and you may be mentioned in the ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS section of this book by way of thanks for contributing to this free eBook!

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

None found by the author.

However, should you, the reader, happen to stumble across something to the contrary, please email the author at FISHE5CA@erau.edu and you may be mentioned in the ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS section of this book by way of thanks for contributing to this free eBook!

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film the temple in Bagan, pictured above.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?