140 India

Three equal horizontal bands of saffron (subdued orange) (top), white, and green, with a blue chakra (24-spoked wheel) centered in the white band. Saffron represents courage, sacrifice, and the spirit of renunciation. White signifies purity and truth. Green stands for faith and fertility. The blue chakra symbolizes the wheel of life in movement and death in stagnation.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

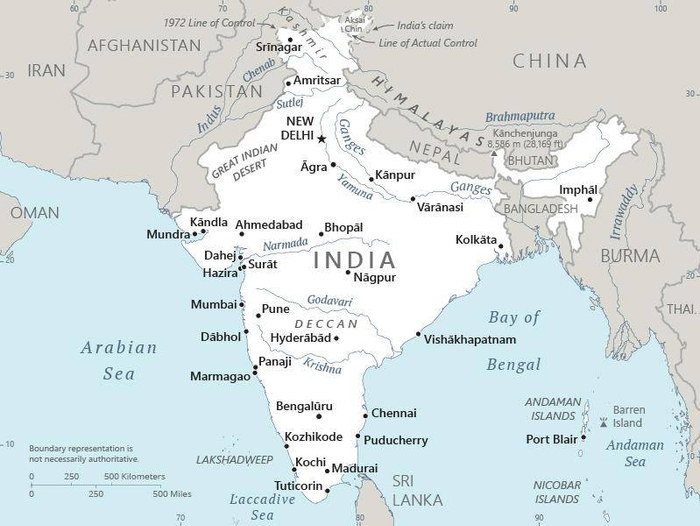

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

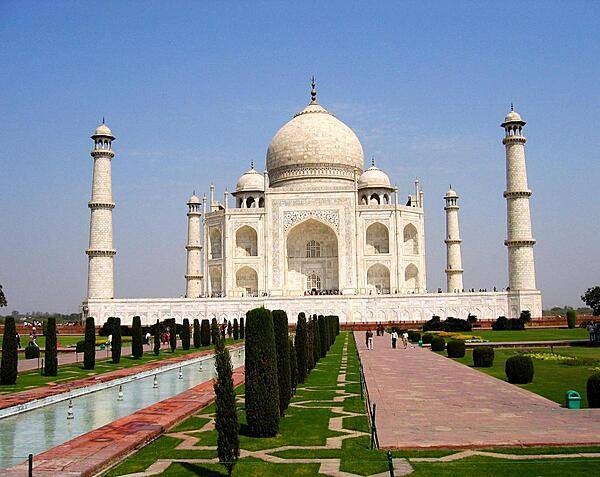

The Taj Mahal was built by Emperor Shah Jahan between 1632 and 1653 to honor the memory of his favorite wife. Located 125 miles from New Delhi in Agra, it took nearly 22 years, 22,000 workers, and 1,000 elephants to complete the white marble mausoleum. The structure became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, the architects of India’s constitution, though drawing on many external sources, were most heavily influenced by the British model of parliamentary democracy. In addition, a number of principles were adopted from the Constitution of the United States of America, including the separation of powers among the major branches of government, the establishment of a supreme court, and the adoption, albeit in modified form, of a federal structure (a constitutional division of power between the union [central] and state governments). The mechanical details for running the central government, however, were largely carried over from the Government of India Act of 1935, passed by the British Parliament, which served as India’s constitution in the waning days of British colonial rule.

The new constitution promulgated on January 26, 1950, proclaimed India “a sovereign socialist secular democratic republic.” With 395 articles, 10 (later 12) schedules (each clarifying and expanding upon a number of articles), and more than 90 amendments, it is one of the longest and most detailed constitutions in the world. The constitution includes a detailed list of “fundamental rights,” a lengthy list of “directive principles of state policy” (goals that the state is obligated to promote, though with no specified timetable for their accomplishment [an idea taken from the Irish constitution]), and a much shorter list of “fundamental duties” of the citizen.

The remainder of the constitution outlines in great detail the structure, powers, and manner of operation of the union (central) and state governments. It also includes provisions for protecting the rights and promoting the interests of certain classes of citizens (e.g., disadvantaged social groups, officially designated as “Scheduled Castes” and “Scheduled Tribes”) and the process for constitutional amendment. The extraordinary specificity of India’s constitution is such that amendments, which average nearly two per year, have frequently been required to deal with issues that in other countries would be handled by routine legislation. With a few exceptions, the passage of an amendment requires only a simple majority of both houses of parliament, but this majority must form two-thirds of those present and voting.

The three lists contained in the constitution’s seventh schedule detail the areas in which the union and state governments may legislate. The union list outlines the areas in which the union government has exclusive authority, which include foreign policy, defense, communications, currency, taxation on corporations and nonagricultural income, and railroads. State governments have the sole power to legislate on such subjects as law and order, public health and sanitation, local government, betting and gambling, and taxation on agricultural income, entertainment, and alcoholic beverages. The items on the concurrent list include those on which both the union government and state governments may legislate, though a union law generally takes precedence; among these areas are criminal law, marriage and divorce, contracts, economic and social planning, population control and family planning, trade unions, social security, and education. Matters requiring legislation that are not specifically covered in the listed powers lie within the exclusive domain of the central government.

An exceedingly important power of the union government is that of creating new states, combining states, changing state boundaries, and terminating a state’s existence. The union government may also create and dissolve any of the union territories, whose powers are more limited than those of the states. Although the states exercise either sole or joint control over a substantial range of issues, the constitution establishes a more dominant role for the union government.

The three branches of the union government are charged with different responsibilities, but the constitution also provides a fair degree of interdependence. The executive branch consists of the president, vice president, and a Council of Ministers, led by the prime minister. Within the legislative branch are the two houses of parliament, the lower house, or Lok Sabha (House of the People), and the upper house, or Rajya Sabha (Council of States). The president of India is also considered part of parliament. At the apex of the judicial branch is the Supreme Court, whose decisions are binding on the higher and lower courts of the state governments.

India’s head of state is the president who is elected to a five-year renewable term by an electoral college consisting of the elected members of both houses of parliament and the elected members of the legislative assemblies of all the states. The vice president, chosen by an electoral college made up of only the two houses of parliament, presides over the Rajya Sabha. If the president dies or otherwise leaves office, the vice president assumes the position until an election can be held.

The powers of the president are largely nominal and ceremonial, except in times of emergency, and the president normally acts on the advice of the prime minister. The proper limits of the president’s power are sometimes a matter for debate. The president may, however, proclaim a national state of emergency when there is perceived to be a grave threat to the country’s security or impose direct presidential rule at the state level when it is thought that a particular state legislative assembly has become incapable of functioning effectively. The president may also dissolve the Lok Sabha and call for new parliamentary elections after a prime minister loses a vote of confidence.

Effective executive power rests with the Council of Ministers, headed by the prime minister, who is chosen by the majority party or coalition in the Lok Sabha and is formally appointed by the president. The Council of Ministers, also formally appointed by the president, is selected by the prime minister. The most important group within the council is the cabinet. Cabinet portfolios are assigned partly on the basis of interest and competence but also on the basis of demonstrated loyalty to the ruling party or party leader and on the implicit need to represent the country’s major regions and population groups (e.g., based on religion, language, caste, and gender). The prime minister and the Council of Ministers remain in power throughout the term of the Lok Sabha, unless they lose a vote of confidence.

Of the two houses of parliament, the more powerful is the Lok Sabha, in which the prime minister leads the ruling party or coalition. The constitution limits the number of elected members of the Lok Sabha to 530 from the states and 20 from the union territories, allotted roughly in proportion to their population. The president may also nominate two members of the Anglo-Indian community if it appears that this community is not being adequately represented. Members of the Lok Sabha serve for terms of five years, unless the house is dissolved before that.

Membership in the Rajya Sabha is not to exceed 250. Of these members, 12 are nominated by the president to represent literature, science, art, and social service, and the balance are proportionally elected by the state legislative assemblies. The Rajya Sabha is not subject to dissolution, but one-third of its members retire at the end of every second year. Legislative bills may originate in either house—except for financial bills, which may originate only in the Lok Sabha, and require passage by simple majorities in both houses in order to become law.

The day-to-day functioning of the government is performed by permanent ministries and other public service agencies. These are led by members of the Indian Administrative Service and other specialized services, who are chosen by competitive examination. Rules of recruitment and retirement and conditions of service are determined by the Union Public Service Commission (or, for state governments, by state public service commissions). There has been a steady proliferation of agencies and growth in the size of the bureaucracy since independence, with a concomitant increase in regulations, which often impede, rather than facilitate, administration.

India’s foreign policy has been officially one of nonalignment with any of the world’s major power blocs. The country was a founding member of the Nonaligned Movement during the Cold War. India has also been a major player among the group of more than 100 low-income countries, loosely described as the “Global South,” that have sought to deal collectively in economic matters with the industrialized states of the “Global North.”

India has maintained its membership in the Commonwealth (formerly the British Commonwealth of Nations), and in 1950 it became the first Commonwealth country to change from a dominion to a republic. It was a charter member, even though not yet independent, of the United Nations (as it was of the earlier League of Nations) and has played an active role in virtually all the organs within the United Nations system. In 1985 India joined six neighboring countries in launching the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation.

The government structure of the states, defined by the constitution, closely resembles that of the union. The executive branch is composed of a governor, like the president, a mostly nominal and ceremonial post, and a council of ministers, led by the chief minister.

All states have a Vidhan Sabha (Legislative Assembly), popularly elected for terms of up to five years, while a small (and declining) number of states also have an upper house, the Vidhan Parishad (Legislative Council), roughly comparable to the Rajya Sabha, with memberships that may not be more than one-third the size of the assemblies. In these councils, one-sixth of the members are nominated by the governor, and the remainder are elected by various categories of specially qualified voters. State governors are also regarded as members of the legislative assemblies, which they may suspend or dissolve when no party is able to muster a working majority.

Each Indian state is organized into a number of districts, which are divided for certain administrative purposes into units variously known as tahsils, taluqs, or subdivisions. These are further divided into community development blocks, each typically consisting of about 100 villages. Superimposed on these units is a three-tiered system of local government. At the lowest level, each village elects its own governing council (gram pancayat). The chairman of a gram pancayat is also the village representative on the council of the community development block (pancayat samiti). Each pancayat samiti, in turn, selects a representative to the district-level council (zila parishad). Separate from this system are the municipalities, which generally are governed by their own elected councils.

From the state down to the village, government appointees administer the various government departments and agencies. Financial grants from higher levels, often made on a matching basis, provide developmental incentives and facilitate the execution of desired projects. Approving, withholding, or manipulating grants, however, often serves as a lever for the accumulation of personal power and as a vehicle of corruption.

The tradition of an independent judiciary has taken strong root in India. The Supreme Court, whose presidentially appointed judges may serve until the age of 65, determines the constitutional validity of union government legislation, adjudicates disputes between the union and the states (as well as disputes between two or more states), and handles appeals from lower-level courts. Each state has a high court and a number of lower courts. The high courts may rule on the constitutionality of state laws, issue a variety of writs, and serve as courts of appeal from the lower courts, over which they exercise general oversight.

Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA)

Located at Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan at the Safdarjung Airport in New Delhi, the Ministry of Civil Aviation is responsible for formulation of national policies and programs for the development and regulation of the Civil Aviation sector in the country. It is responsible for the administration of the Aircraft Act, 1934, Aircraft Rules, 1937 and various other legislations pertaining to the aviation sector in the country. This Ministry exercises administrative control over attached and autonomous organizations like the Directorate General of Civil Aviation, Bureau of Civil Aviation Security and Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Uran Akademi and affiliated Public Sector Undertakings like Airports Authority of India and Pawan Hans Helicopters Limited. The Commission of Railway Safety, which is responsible for safety in rail travel and operations in terms of the provisions of the Railways Act, 1989 also comes under the administrative control of this Ministry. The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) is the regulatory body in the field of Civil Aviation, primarily dealing with safety issues. It is responsible for regulation of air transport services to/from/within India and for enforcement of civil air regulations, air safety, and airworthiness standards. The DGCA also co-ordinates all regulatory functions with the ICAO.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

Drone Regulations

UAS Rules – Main Page

DRONE TRAINING CIRCULAR 01 OF 2022

Digital Sky – Get your Import Clearance/ UIN/ UAOP

National Counter Rogue Drones Guidelines

2019 – National Counter Rogue Drones Guidelines

2025 – Bhargavastra: India’s Breakthrough Counter-Drone System

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

2023 – India unveils ambitious AAM plan

2024 – Aerodrome Advisory Circular on Vertiport

Bilateral agreements facilitate the reciprocal airworthiness certification of civil aeronautical products imported/exported between two signatory countries. A Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement (BAA) or Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement (BASA) with Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA) provides for airworthiness technical cooperation between the FAA and its counterpart civil aviation authorities.

Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement – Executive Agreement

Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness

Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness, Amendment 1

2016 Notification of Policy Deviation Memorandum for FAA Order 8130.21H

Obtaining Certification Approval from this Country

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

2025 – Urban-Air Port partners with Nalwa Aero in India

2025 – India’s ePlane Set To Start Flight Testing Two-seat eVTOL Aircraft

2025 – Vjaitra Air Mobility takes wraps off VJ220 eVTOL aircraft

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 2 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

2025 – LYNEports, Sarla launch AAM partnership for cities across India

2025 – Indian Air Mobility Startup Sarla Aviation Raises $10 Million

2025 – JetSetGo to use Eve Air Mobility’s Vector software in India

2025 – Hunch Mobility to use Electra EL9 for regional service in India

2025 – Indian government to start air taxi routes in major cities during 2026

2024 – Report explores operational concepts for advanced air mobility in India

2024 – India’s DGCA issues guidance for VTOL type certification

2024 – Prime Minister Modi: AAM will soon be reality in India

2024 – DGCA releases guidelines for vertiport design, operations in India

2024 – SkyDrive and Government of Gujarat in India Sign Strategic Partnership

2023 – Eve Air Mobility and Hunch Mobility Collaborating to Bring eVTOL Flights to Bangalore

2023 – BLADE Air Mobility signs MoU with Jaunt for Operations in India

2023 – Blade, Jaunt Air Mobility partner to launch UAM operations in India

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone to film the Taj Mahal, pictured above.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?