37 Australia

Blue with the flag of the UK in the upper hoist-side quadrant and a large seven-pointed star in the lower hoist-side quadrant known as the Commonwealth or Federation Star, representing the federation of the colonies of Australia in 1901. The star depicts one point for each of the six original states and one representing all of Australia’s internal and external territories. On the fly half is a representation of the Southern Cross constellation in white with one small, five-pointed star and four larger, seven-pointed stars.

Flag courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Map courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

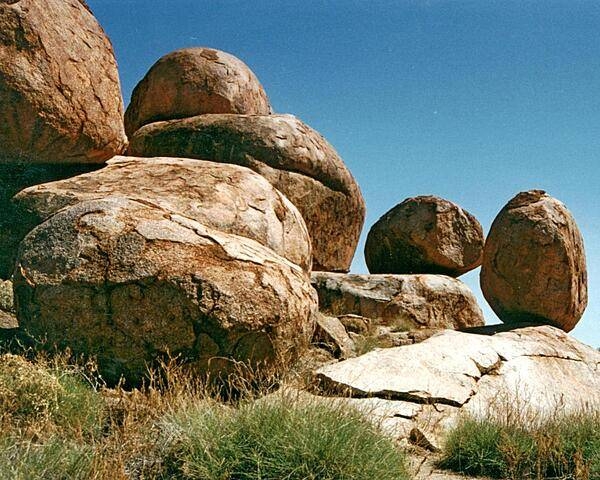

Some of the granite boulders at Devils Marbles Conservation Reserve near Wauchope, in the Northern Territory. The marbles were formed through various geological processes including chemical and mechanical weathering.

Photo courtesy of the CIA World Factbook

Government

According to Britannica, Australia’s constitution, which can be considered crudely as an amalgam of the constitutional forms of the United Kingdom and the United States, was adopted in 1900 and entered into force in 1901. It established a constitutional monarchy, with the British monarch, represented locally by a governor-general, the reigning sovereign of Australia. Likewise, Australia adopted the British parliamentary model, with the governments of the Commonwealth of Australia and of the Australian states chosen by the members of the parliaments. Similar to the United States, Australia is a federation, and the duties of the federal government and the division of powers between the Commonwealth and the states are established in a written constitution. Under the constitution, the federal government has responsibility for defense, foreign policy, immigration, customs and excise, and the post office. Those powers not given to the federal government in the constitution (the “residual powers”) are left to the states, which are responsible for justice, education, health, and internal transport. In keeping with federalism, the constitution can be altered only by majorities in both federal houses of the legislature followed by a referendum that gains the consent of a majority of all the electors and a majority in at least four of the six states. Constitutional disputes are resolved by the High Court of Australia. Although the British monarch is Australia’s formal head of state, the sovereign’s functions are almost entirely formal and decorative and, except when the monarch is in Australia, are exercised by a governor-general who resides in Canberra and by the state governors. Although formally the governor-general and the governors are appointed by the monarch, they are invariably recommended by the Australian governments. By convention, the prime minister (the leader of the party or coalition of parties victorious in the general election) is the country’s head of government.

Australia’s legislature is bicameral. The House of Representatives (the lower house) comprises 150 members, including two each from the Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory. Members are elected for three-year terms and are responsible for choosing the government. The Senate consists of 76 members; each state has 12 senators, and there are two senators each from the Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory. Senators representing the states serve six-year terms, while territorial senators serve three-year terms. Government ministers are drawn from both the House and the Senate.

There are hundreds of local government authorities in Australia. The powers of local authorities are derived from legislation adopted in each state and territory, and their functions vary considerably. Typically, these functions include waste and sanitary services, water, roads, land use, inspection and licensing, maintaining public libraries and recreational facilities, town planning, and the promotion of district attractions and amenities. In some areas, particularly the densely settled suburbs, its role includes the operation of transport and energy systems. Local governments receive funding from their respective states and collect taxes.

The Australian legal system is based on the common law of England, and many laws are identical with those laid down in acts of the British Parliament. The administration of the law is largely in the hands of the states, each of which has a series of courts culminating in a supreme court. Between them these courts have comprehensive responsibilities extending to all matters of state (and to most matters of federal) jurisdiction.

The High Court of Australia, the federal supreme court, consists of a chief justice and six other justices, each of whom is formally appointed by the governor-general. It exercises general appellate jurisdiction over all other federal and state courts and is given the special duty to decide disputes involving the interpretation of the federal constitution and acts of the federal parliament. The High Court also has original jurisdiction on matters such as Australia’s obligations under international treaties, issues affecting foreign representatives, and disputes between states. The court is well respected by legal authorities both inside and outside Australia. The Federal Court of Australia combines the jurisdictions formerly exercised by the Federal Court of Bankruptcy and the Australian Industrial Court.

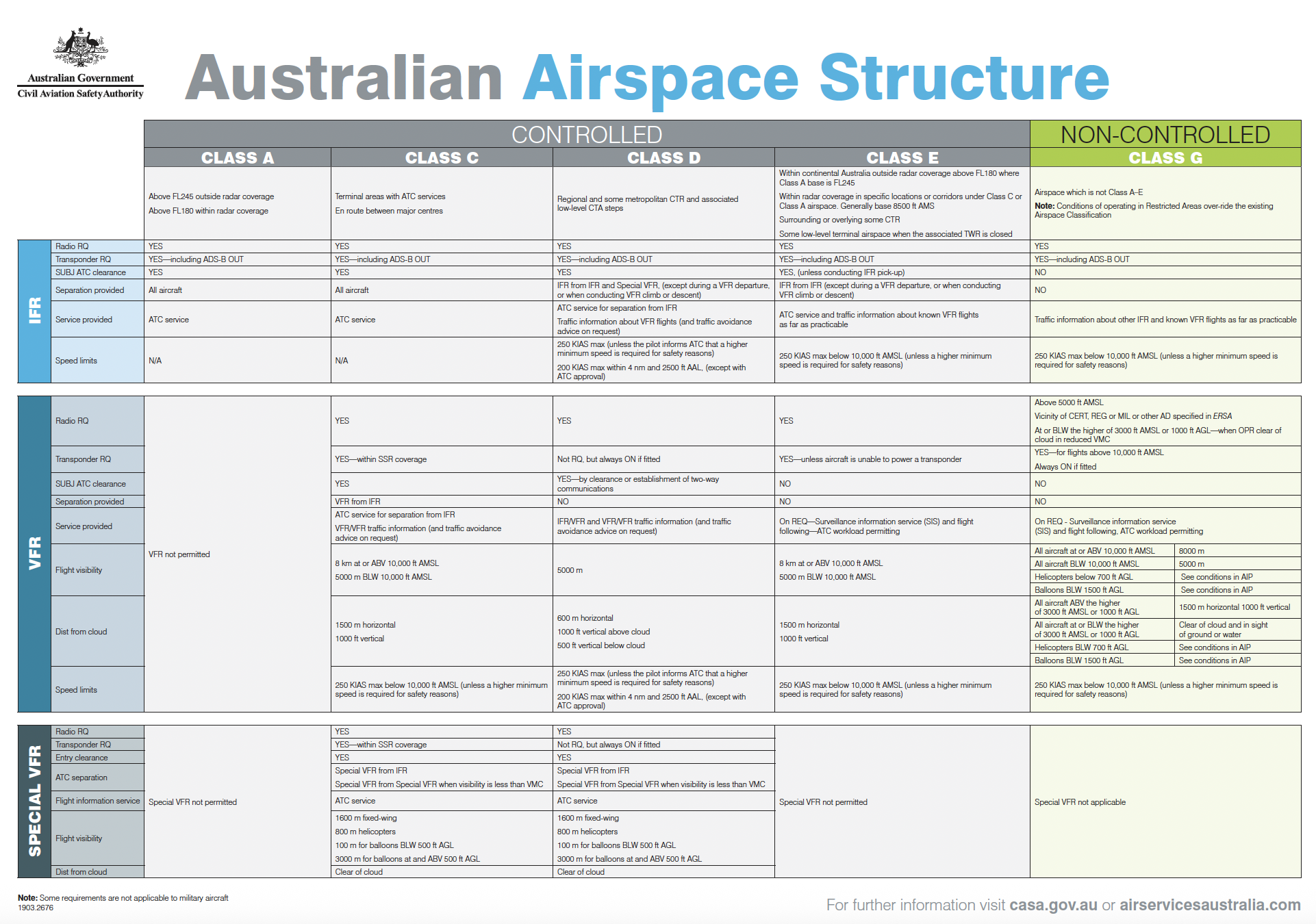

Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA)

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) is a government body that regulates aviation safety in Australia. They license pilots, register aircraft, oversee aviation safety and promote safety awareness. They also make sure that the aviation community and the public use and administer Australian airspace safely. In July 1995, they were established as an independent statutory authority. They operate within a legislative framework made up of acts, regulations, associated legislative instruments and guidance material. The Civil Aviation Act 1988 describes our role. The Act also forms the basis of the Civil Aviation Safety Regulations. These regulations are broken into parts, which may have an associated Manual of Standards, as well as supporting guidance materials. They employ about 800 people across Australia. They work with the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts and Airservices Australia in a tripartite structure to provide safe aviation in Australia.

Pacific Aviation Safety Office (PASO)

The Pacific Aviation Safety Office (PASO) is an international organization providing quality aviation safety and security service for Member States in the Pacific.

PASO is the sole international organization responsible for regional regulatory aviation safety oversight service for the 10 Pacific States who are signatories to the Pacific Islands Civil Aviation Safety and Security Treaty (PICASST).

The current PICASST signatories are the Pacific nations of Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. Associate Members of PASO are Australia, Fiji and New Zealand. Government representatives from these nations make up the PASO Council.

Airspace

SkyVector – Google Maps – ADS-B Exchange

ICAO countries publish an Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). This document is divided into three parts: General (GEN), En Route (ENR) and Aerodromes (AD). ENR 1.4 details the types of airspace classes they chose to adopt from classes A through G.

Airservices Australia

Airservices Australia is a government-owned organization responsible for the safety of 11% of the world’s airspace. They are responsible for the safe and efficient management of Australia’s skies and the provision of aviation rescue fire fighting services at Australia’s busiest airports. Airservices provide safe, secure, efficient and environmentally responsible services to the aviation industry.

They have a page dedicated to Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) in controlled airspace. Note the Obstacle Limitation Surfaces (OLS) for different regions!

See CASA for additional information including links to legislation, advisory circulars, guides to recreational and commercial flying, safety brochures, and forms. See Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) for information on RPAS safety and occurrence reporting.

Drone Regulations

Drone Laws for Australia.

The Australian government has published a digital map of drone laws that details regulations in 7,610 areas across the country to help increase awareness and compliance among drone operators.

The drone safety rules, (with video!) also known as the standard operating conditions, apply to all types of drones and remote-controlled aircraft.

Before you fly, you check your state or territory laws:

- New South Wales (NSW)

- Victoria (VIC)

- Tasmania (TAS)

- South Australia (SA) – National parks

- South Australia (SA) – ForestrySA forest reserves

- Western Australia (WA)

- Northern Territory (NT)

- Queensland (QLD)

- Australian Capital Territory (ACT).

There may also be laws that apply to the launching and landing of drones in your local park or sports oval. Check if local laws apply before you fly on council land.

Beyond Visual Line of Sight

Apply for beyond visual line-of-sight approvals

Beyond visual line-of-sight exam

2025 – Australian BVLOS Operations A-Z: The Ultimate Guide to Success

C-UAS

17 Destruction of aircraft

(1) A person must not intentionally destroy a Division 3 aircraft.

Penalty: Imprisonment for 14 years.

(2) For the purposes of an offense against subsection (1), absolute liability applies to the physical element of circumstance of the offense, that the aircraft is a Division 3 aircraft.

Australia Radiocommunications Act 1992

The object of Australia’s Radiocommunications Act of 1992 is to promote the long-term public interest derived from the use of the spectrum. The Act provides for the management of the spectrum in a manner that:

- facilitates the efficient planning, allocation and use of the spectrum; and

- facilitates the use of the spectrum for:

- commercial purposes; and

- defense purposes, national security purposes and other non‑commercial purposes (including public safety and community purposes); and

- supports the communications policy objectives of the Commonwealth Government.

Radiocommunications (Exemption – Remotely Piloted Aircraft Disruption) Determination 2022

Radiocommunications (Jamming Equipment) Permanent Ban 2023

Radiocommunications Act 1992 – Includes amendments: Act No. 39, 2024

Australian Communications and Media Authority

Exemptions for banned equipment

The Australian Government is progressing a holistic suite of policies and programs to address security and community safety risks of negligent and malicious drone and Advanced Air Mobility use in Australia.

National Drone Detection Network

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Regulations & Policies

CASA – Advanced Air Mobility

Part 21 of CASR Certification and airworthiness requirements for aircraft and parts

2024 – The Australian Government released the Aviation White Paper – Towards 2050 on 26 August 2024. The Aviation White Paper sets out the government’s vision for aviation towards 2050 and will deliver a range of initiatives to ensure a safe, competitive, productive and sustainable sector.

The roadmap sets out Australia’s future approach to aviation safety regulation and oversight for remotely piloted aircraft systems and advanced air mobility. It has been developed as an initiative under the National Emerging Aviation Technologies Policy Statement. To create the roadmap, the Aviation Safety Advisory Panel set up a technical working group to help the co-design process with industry.

The Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) and Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Strategic Regulatory Roadmap outlines Australia’s approach for RPAS and AAM regulations over the next 10 to 15 years. It sets out their long-term plan for safely integrating these technologies into Australia’s airspace and future regulatory system, alongside traditional aviation.

The RPAS and AAM Strategic Regulatory Roadmap Glossary

The roadmap has been developed using 6 regulatory areas across 4 time horizons. These guide the activities set out in this roadmap.

Airspace and traffic management

CASA released AC 139.V-01v1.0, an advisory circular providing guidance for vertiport design.

AAM Industry Vision and Roadmap

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Action Plan for the State of Victoria

Bilateral agreements facilitate the reciprocal airworthiness certification of civil aeronautical products imported/exported between two signatory countries. A Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement (BAA) or Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement (BASA) with Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (IPA) provides for airworthiness technical cooperation between the FAA and its counterpart civil aviation authorities.

Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement – Executive Agreement

Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (Revision 1)

Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (Amendment 1 to Revision 1)

Implementation Procedures for Airworthiness (Addendum 1 to Amendment 1)

Revised Export Documentation Requirement For Engines And Propellers

2016 Notification of Policy Deviation Memorandum for FAA Order 8130.21H

Obtaining Certification Approval from this Country

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) News

2025 – Skyportz introduces modular AAM vertipad prototype

2025 – Australia ADS-B Plan Comes as U.S. Weighs Part 108 Right-of-Way

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the July 2025 Global AAM Forum.

2025 – Vertiia Hydrogen-Electric VTOL aircraft gets government support

2025 – AMSL Aero receives grant for hydrogen-electric power system

2025 – Stralis Signs Up U.S. Launch Customer for Hydrogen-powered Bonanza

2025 – Skyportz releases modular vertipad animation (VIDEO)

2025 – Australia’s CASA seeks feedback on vertical flight aircraft facilities

2025 – Australian airport plans electric air taxi network

2025 – AMSL Aero advances hydrogen testing of eVTOL aircraft

2025 – AMSL Aero strikes deal to refuel hydrogen-powered “Vertiia” aircraft at Archerfield Airport

2025 – AMSL to develop hydrogen refueling infrastructure at YBAF

2025

Video courtesy of Advanced Air Mobility Institute from the January 2025 Global AAM Forum. Complete session for Day 3 of this Forum is available on the Advanced Air Mobility Institute YouTube Channel

2024 – Skyportz welcomes the release of air taxi roadmap in Australia

2024 – Agreement to Support eVTOLs at Archerfield Airport

2024 – Hydrogen-Powered Long-Range eVTOL Makes First Untethered Flight

2024 – Future Hydrogen VTOL Flies Free

2024 – Wisk Forms MoU for Australian Autonomous Air Travel

2024 – Australia’s ATC Agency Prepares to Integrate Autonomous eVTOL Aircraft

2024 – Wisk Aero to advance air taxi network in Australia

2024 – Skyportz and Microflite to transform Melbourne with air taxi vertiports

2024 – Skyportz, Microflite to develop vertiport network in Melbourne

2024 – Thales, Underwood to develop AAM center in Australia

2024 – Brisbane eyes electric air taxi services for 2032 Summer Olympics

2024 – FlyOnE to build electric aircraft training center in Australia

2024 – Blueflite to produce hydrogen fuel cells for drones in Australia

2024 – Skyports partners with Wagner on vertiports in Australia

2024 – Skyports builds momentum through partnership with Australian real estate developer

2024 – Why Australia might be ideal for electric flying taxis

2024 – Joby seeks eVTOL aircraft certification in Australia, Japan, UK

2024 – LYNEports Integrates Australian Vertiport Design Guidelines into AAM Planning Software

2024 – Wilbur Air to operate Crisalion Integrity eVTOL in Australia

2024 – Partnership to Bring Autonomous AAM Aircraft to Queensland

2024 – Wisk Aero, Skyports expand partnership in Australia

2024 – Skyportz welcomes new action plan for advanced air mobility in Victoria, Australia

2024 – Skyportz supports government plans for AAM in Victoria, Australia

2024 – AMSL Aero and Aeria bring hydrogen aviation fuel to Bankstown Airport in Australia

2024 – Australia approves funding for emerging aviation technology

2024 – “First AAM operations in Australia in 2027; industry will develop in three waves” – AAUS

2024 – Advanced Air Mobility Trials to commence this year

2023 – eVTOL stakeholders discuss 2027 target launch of AAM in Australia

2023 – Pelligra and Skyportz Partner to Explore Australian Vertiport Opportunities

2023 – Skyway, Skyportz collaborate on Australian UAM

2023 – Skyportz partners with Perth’s Electro.Aero to power plans for national vertiport network

Short Essay Questions

Scenario-Based Question

You have been hired by a Drone Startup Company. Your boss has immediately assigned this job to you.

They need you to prepare a one-page memo detailing the legalities of using a drone at Devils Marbles Conservation Reserve near Wauchope, in the Northern Territory, pictured above.

They need you to mention any national laws and local ordinances.

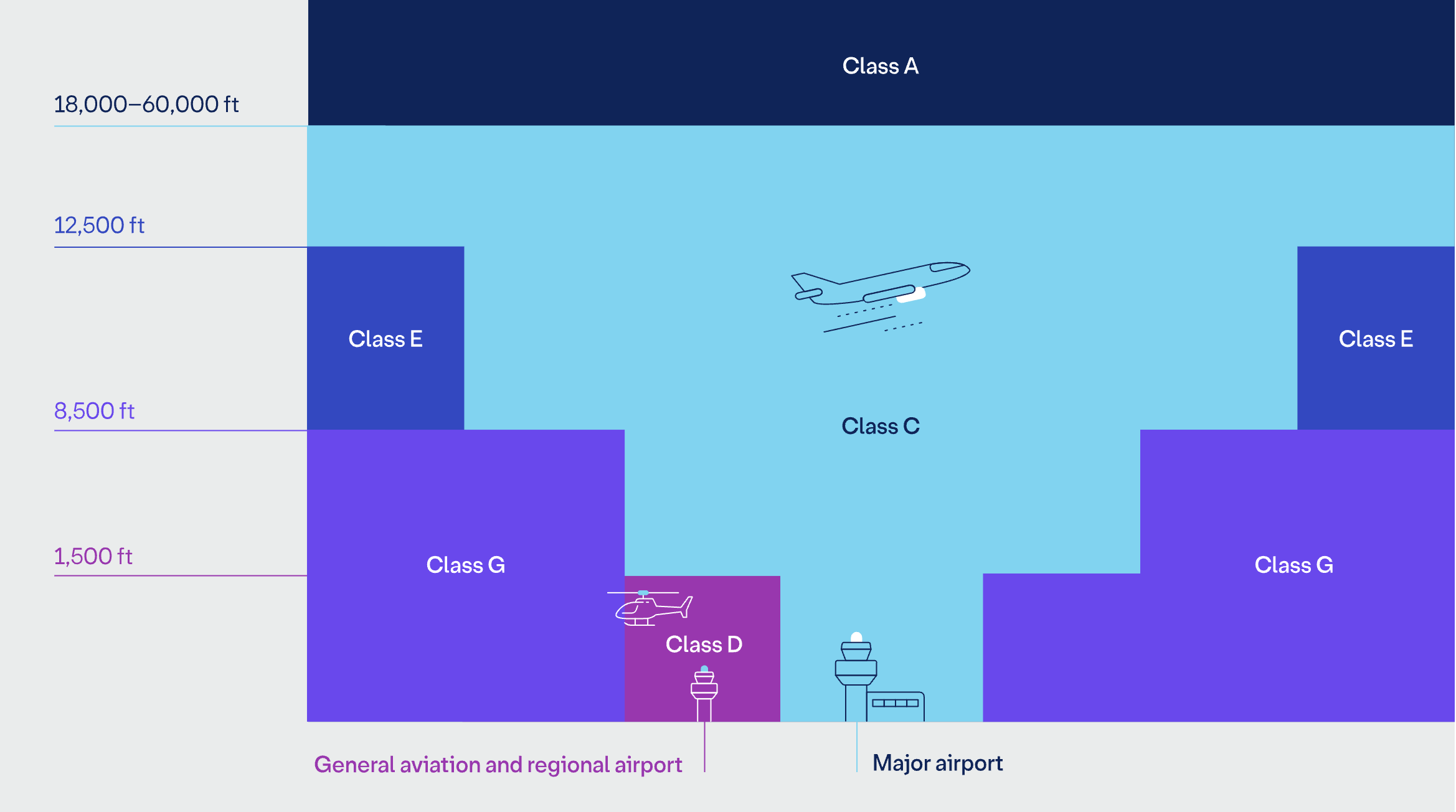

They specifically want to know what airspace (insert pictures) you will be operating in and whether or not you need an airspace authorization.

Does it matter whether or not you are a citizen of the country?

Lastly, there is a bonus for you if, as you scroll through this chapter, you find any typos or broken links!

Short Essay Questions

- What are the drone categories?

- How is registration addressed?

- How is remote ID addressed?

- What are the model aircraft rules?

- What are the commercial drone rules?

- Are there waivers or exemptions to the rules? If so, for what?

- Would you share a link to an interactive airspace map?

- How is BVLOS addressed?

- How can you fly drones at night?

- How can you fly drones over people?

- Where do you find drone NOTAMs?

- What are the rules for drone maintenance?

- What are the rules for an SMS program?

- What are some unique rules not mentioned above?

- What are the C-UAS rules?

- What are the AAM rules?