Key Theories and Figures in Resilience Research

Key Theories in Resilience Research

Resilience research has been informed by several key theories, driven by pioneering figures in the field. These theories and figures have shaped our understanding of the complex processes underlying resilience.

When you have exhausted all possibilities, remember this: you haven’t. – Thomas A. Edison

The Risk and Protective Factors Model of Resilience

Central to understanding resilience is the Risk and Protective Factors Model. This model has been one of the most influential in shaping resilience research. It proposes that adversity and positive adaptation are not determined solely by individual traits. Instead, this model delineates between factors that increase the probability of negative outcomes in the face of adversity (risks) and factors that enhance the likelihood of positive outcomes (protective factors).

Risk Factors and Their Impact

Risk factors can be understood as conditions or attributes that increase the likelihood of a negative developmental outcome (Masten, 2001). They can emerge from various domains including individual (e.g., genetic vulnerabilities), family (e.g., dysfunctional relationships), and environmental contexts (e.g., socio-economic disadvantages). Notably, risk does not function in isolation. Multiple risk factors can have cumulative effects, making it harder for an individual to maintain resilience when faced with multiple adversities simultaneously (Rutter, 1987). For instance, a child born with a genetic predisposition to anxiety may experience exacerbated symptoms if they also grow up in an unstable home environment.

Protective Factors: Shields Against Adversity

In contrast to risk factors, protective factors are characteristics of individuals, families, communities, or the larger society that act to mitigate risks and foster adaptive outcomes (Garmezy, 1991). These can be internal attributes such as self-esteem, intelligence, or emotion regulation skills. Equally important are external protective factors, like strong family bonds, supportive peer relationships, and connection to community or religious groups.

There’s compelling evidence to suggest that protective factors can moderate the effects of risk. For instance, Werner and Smith (1992) conducted a seminal longitudinal study on children from Kauai, identifying that even amidst high-risk conditions, certain factors like maternal warmth and external support systems aided children in developing successfully.

Interplay Between Risk and Protective Factors

The dynamics between risk and protective factors aren’t purely additive; their interplay can be complex. Rutter (1987) introduced the concept of “steeling effects,” where certain risk experiences, when encountered at a moderate level, can bolster resilience by preparing the individual for future challenges. In such cases, what traditionally might be labeled as a ‘risk’ can become a resilience-enhancing experience.

Furthermore, the efficacy of protective factors might differ depending on the nature and intensity of risks faced. For some individuals, certain protective factors might be especially salient. For example, for a child experiencing parental neglect, a supportive relationship with a teacher might be more influential than for a child without such experience.

Implications for Interventions

Understanding the Risk and Protective Factors Model is pivotal for interventions aimed at fostering resilience. Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, interventions can be tailored to address specific risks while bolstering relevant protective factors. Moreover, it’s crucial to recognize that resilience isn’t just about reducing risk, but also about strengthening resources and capacities. Thus, interventions shouldn’t solely focus on problem reduction but also on enhancing individual, family, and community assets (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000).

The Risk and Protective Factors Model provides a comprehensive framework to understand the intricate dynamics of resilience. By identifying and understanding the balance between risks and protective factors, researchers, clinicians, and policymakers can craft more effective strategies to support individuals in navigating the multifaceted challenges of life.

The Ecological Systems Theory of Resilience

Among the various theories postulated to explain resilience, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory also stands out as particularly influential. It emphasizes the multilayered impact of environmental systems on individual development, and by extension, resilience.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Framework

Bronfenbrenner’s theory, first introduced in the late 1970s, postulates that an individual’s development is influenced by a series of interconnected environmental systems. These range from immediate environments like the family, to more distal systems such as the larger societal and cultural contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

- Microsystem: This layer is the closest to the individual and consists of immediate relationships and settings like family, school, peers, and neighborhood. The dynamics, interactions, and activities within this system play a crucial role in shaping an individual’s resilience.

- Mesosystem: This encompasses the interactions between two or more settings that are significant to the individual, such as the relationship between families and teachers or between the individual’s family and their peer group.

- Exosystem: This system contains the larger social structures that do not directly contain the individual but influence their immediate environment. For instance, a parent’s workplace can indirectly impact a child if job loss or stress is transferred to the home environment.

- Macrosystem: Here, broader societal and cultural norms and attitudes come into play. The overarching belief systems, customs, and values of a culture or subculture can greatly impact an individual’s ability to cope and adapt.

- Chronosystem: This system refers to the patterning of environmental events and transitions over life, as well as sociohistorical circumstances. As an example, growing up during a war or significant societal upheaval can deeply impact an individual’s resilience (Bronfenbrenner, 1986).

Linking Ecological Systems to Resilience

Understanding resilience through Bronfenbrenner’s lens necessitates examining how these systems interplay to either bolster or hinder adaptive capacities. Resilience does not operate in a vacuum; it is fostered or impeded by the interactions of these systems. For instance, a supportive microsystem with nurturing parents and teachers can foster resilience, even in the face of challenging macrosystem factors, like living in a community with prevalent crime or societal unrest (Ungar, 2002).

However, the presence of adverse circumstances in one system does not doom an individual to poor outcomes. Research has shown that positive factors in one system can counteract negatives in another (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). A child growing up in a socio-economically challenged neighborhood (a macrosystem factor) can still demonstrate high resilience if they have a supportive family unit (microsystem) or access to community programs that offer mentorship and support (exosystem). Furthermore, the chronosystem highlights that resilience can change over time based on life events and transitions. An individual might exhibit strong resilience during childhood but face challenges in adolescence due to new external pressures or shifts in their ecological systems.

The Ecological Systems Theory offers a comprehensive framework to understand the multifaceted influences on resilience. By recognizing the complex interplay of systems around an individual, it underscores the need for holistic interventions. Promoting resilience, thus, requires a multi-layered approach, targeting not only the individual but also their broader environment. As the global community grapples with increasing adversities from socio-political unrest to climate change, leveraging insights from the Ecological Systems Theory becomes paramount to fostering a resilient populace.

The Psychological Capital (PsyCap) Theory of Resilience

One of the most potent tools for understanding resilience within organizational settings is the Psychological Capital (PsyCap) theory. PsyCap offers a holistic understanding of individual positive psychological capacities that can be cultivated and managed for performance improvement.

Origins and Core Components of PsyCap

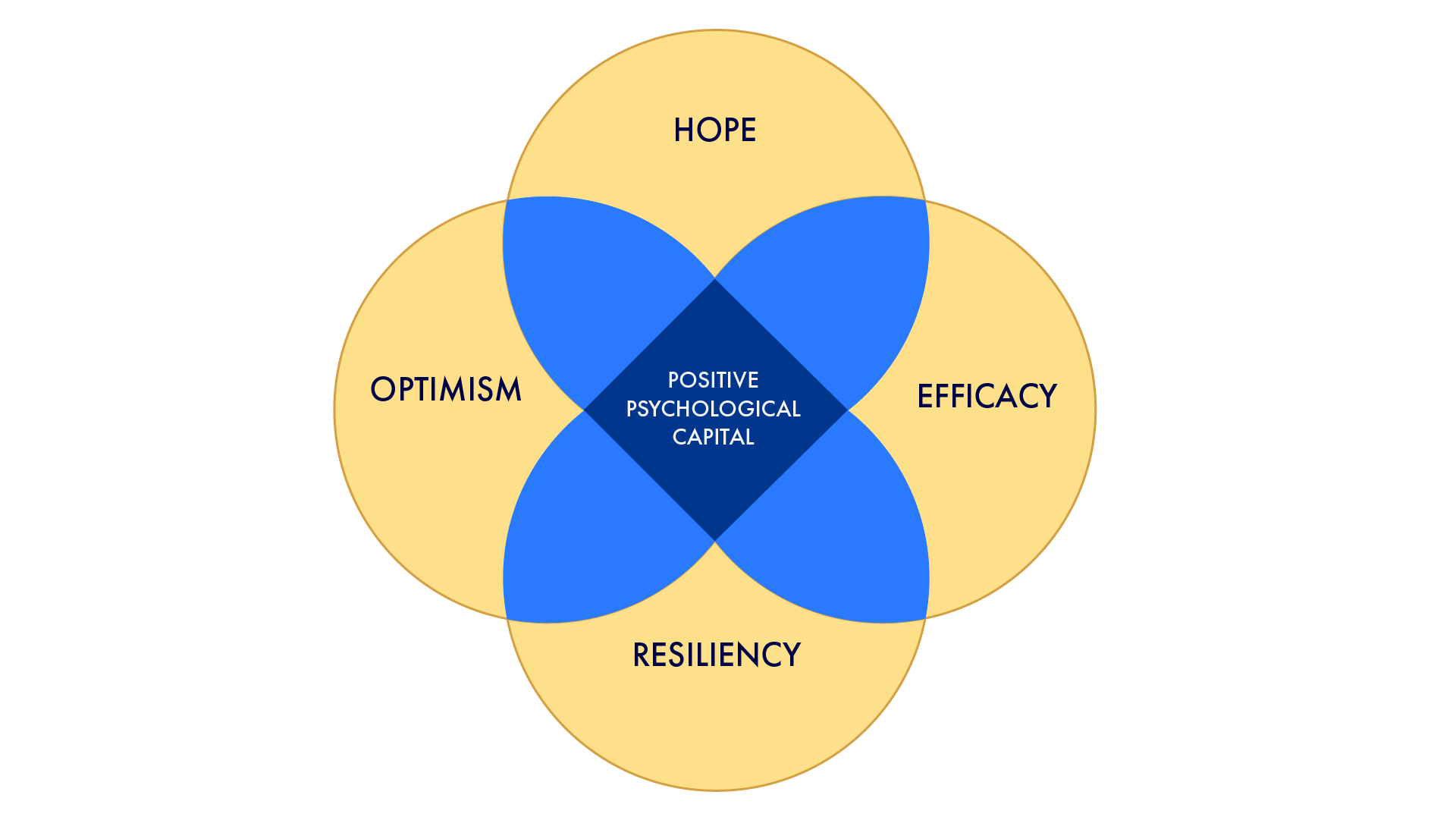

Psychological Capital, coined by Luthans, Youssef, and Avolio (2006), is categorized under the umbrella of positive organizational behavior. Unlike human and social capital, which emphasizes knowledge, skills, abilities, and relationships, PsyCap underscores who people are (their psychological makeup) and who they can become (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017). Four primary components, often referred to as the HERO within, form the pillars of PsyCap:

- Hope: This pertains to the individual’s perseverance toward goals and the capability to redirect paths to goals in order to achieve them.

- Efficacy: It emphasizes an individual’s confidence in allocating the necessary effort to succeed in challenging tasks.

- Resilience: Resilience in PsyCap is defined as the positive psychological capability to rebound, to get back up, and even to surpass in the face of adversity or setback.

- Optimism: This represents the positive attribution of success, both in the present and in the future.

Figure 2.1: The Psychological Capital (PsyCap) Theory of Resilience

Each component has its roots in a wealth of psychological research. For instance, the component of resilience can trace its lineage to the works of pioneers such as Masten (2001) who asserted that resilience is a common phenomenon and can be nurtured to improve life outcomes.

The Role of PsyCap in Fostering Resilience

Resilience, as a standalone component of PsyCap, functions as a reactive mechanism that allows individuals to bounce back from adversities. When integrated within the HERO framework, it becomes proactive, allowing individuals not just to recover but to flourish (Luthans, Vogelgesang, & Lester, 2006). Several empirical studies have confirmed the predictive validity of PsyCap in various outcomes, including job performance, job satisfaction, and well-being. Avey, Reichard, Luthans, and Mhatre (2011) observed that employees with higher levels of PsyCap had a better work performance and satisfaction, while also experiencing lower stress and turnover intentions. This positive correlation is attributed to the resilience fostered by PsyCap, enabling employees to handle work-related challenges more effectively.

PsyCap, as a developmental construct, can be enhanced and fostered, unlike many personality traits that remain relatively stable over time. Through targeted interventions, such as Luthans and colleagues’ (2010) micro-interventions, individuals can develop higher levels of PsyCap, subsequently improving their resilience in the face of challenges.

Implications and Future Directions

In the ever-demanding world of work, challenges are inevitable. However, with the arsenal of PsyCap, organizations can ensure that their employees are not just prepared but are also equipped to grow from such challenges. By integrating PsyCap into training and development programs, organizations can reap the benefits of a more resilient, hopeful, confident, and optimistic workforce. Additionally, PsyCap provides a blueprint for individuals to manage their psychological well-being. By understanding and developing their inherent capacities, individuals can lead a more fulfilling life, both professionally and personally.

While the current body of literature provides substantial evidence of the benefits of PsyCap, there remains ample scope for exploration. Future research can delve into the nuanced interplays between each component of PsyCap and their effects in varied cultural and organizational contexts.

The Psychological Capital (PsyCap) theory offers a comprehensive understanding of the positive psychological resources individuals possess. By emphasizing hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism, PsyCap not only promotes the idea of bouncing back from adversities but also advocates for growth and flourishing. In the organizational context, PsyCap holds immense potential for fostering a resilient and high-performing workforce, making it a valuable asset for both individuals and organizations.

The Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory

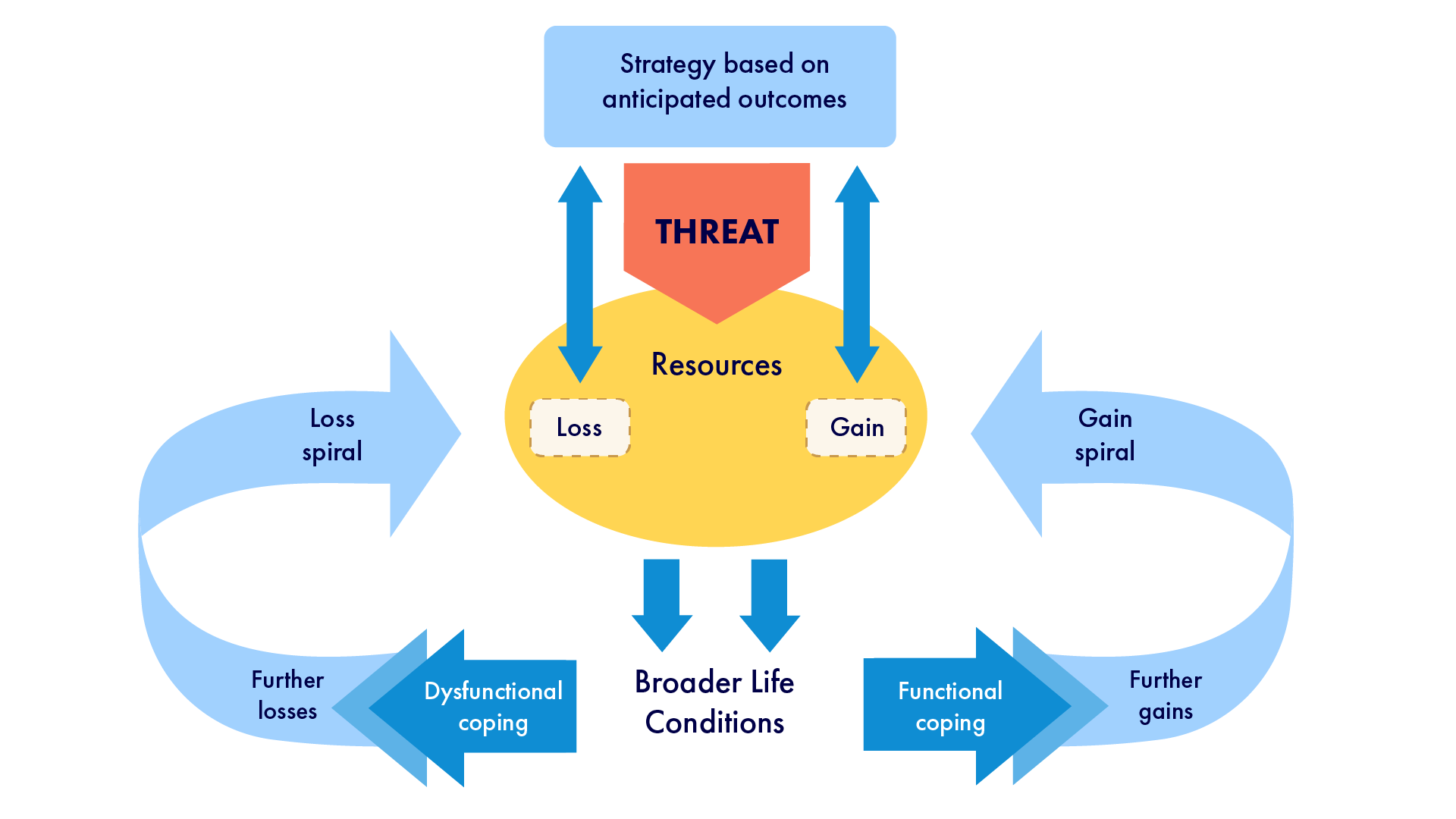

The realm of stress research is one inundated with models and theories seeking to illuminate the complexities of human stress response, its causes, and consequences, all of which can be applied to understand facets of resilience. Among these models, the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, developed by Dr. Stevan E. Hobfoll in 1989, stands out as a profound framework for understanding why individuals experience stress and how they strive to protect and conserve valued resources (Hobfoll, 1989). In the context of resilience, resources could include personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that are valued by the individual or that serve as a means for attainment of these valued outcomes. Stress occurs when there is a threat of loss of these resources, actual loss, or lack of gained resources after significant effort. Resilience, in this view, is about the successful conservation of resources or swift recovery following loss.

Fundamental Premise of the COR Theory

At its core, the COR theory posits that individuals strive to obtain, retain, foster, and protect that which they centrally value (Hobfoll, 1989). These valuable entities are termed “resources,” and they span a diverse range, from tangible assets such as property and money, to personal characteristics like self-esteem and knowledge, to social support and familial ties. The primary emphasis of COR is on the role these resources play in stress experiences: stress occurs when these valued resources are threatened with loss, are actually lost, or when there is a lack of expected resource gain following significant investment (Hobfoll, 2001).

The Loss and Gain Spirals

A key tenet of the COR theory is the principle of resource loss and gain spirals. Hobfoll (2001) emphasizes that resource loss is disproportionately more salient than resource gain. In simpler terms, the negative impact of resource loss is much more potent than the positive effects of resource gains. This inherent asymmetry in the way humans perceive loss and gain sets the stage for potential spirals, where initial loss or gain leads to further loss or gain in a cascading manner. For example, a person who loses a job (a primary resource) might also lose self-esteem, social status, and the ability to afford necessities, thus precipitating further resource loss. Conversely, a gain in resources, like a promotion, can boost confidence and provide new opportunities, leading to a gain spiral. The potential for these spirals implies that individuals and communities can rapidly descend into severe resource depletion or ascend to significant resource affluence.

Figure 2.2: The Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory

The Role of Resource Investment

Another integral component of the COR theory is the concept of resource investment. Individuals invest their resources with the hope of accumulating more resources in the future. Accordingly, an individual might invest time and energy (resources) into education (resource investment) expecting a good job (resource gain) in the future. However, when the anticipated returns on these investments aren’t realized, it can lead to stress (Hobfoll, 2001).

Implications of the COR Theory

Understanding the COR theory has several significant implications. First, it underscores the importance of protecting and conserving resources as a proactive strategy to prevent stress. Organizations and policymakers can use this insight to design interventions that safeguard the resources of individuals and communities, thus averting potential loss spirals.

Additionally, the theory provides a framework for understanding the differential impact of stress on various populations. Those with fewer resources are more vulnerable to resource loss and, therefore, more prone to experiencing stress, illuminating why marginalized and lower socioeconomic populations often bear a disproportionate burden of stress-related ailments (Hobfoll, 2001). Lastly, from a clinical perspective, interventions can be tailored to help individuals recognize their resource reservoirs and employ strategies to prevent their depletion, aiding in stress management and promoting well-being.

In the expanse of stress research, the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory offers a compelling lens to view the intricate dynamics of stress, resource loss, and gain, thus providing insight into individual differences in resilience. By understanding the pivotal role of valued resources in the human experience of stress and the cascading effects of resource loss and gain, individuals, organizations, and societies can better navigate the challenges of the modern world and foster environments that promote resource conservation and well-being.

The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions

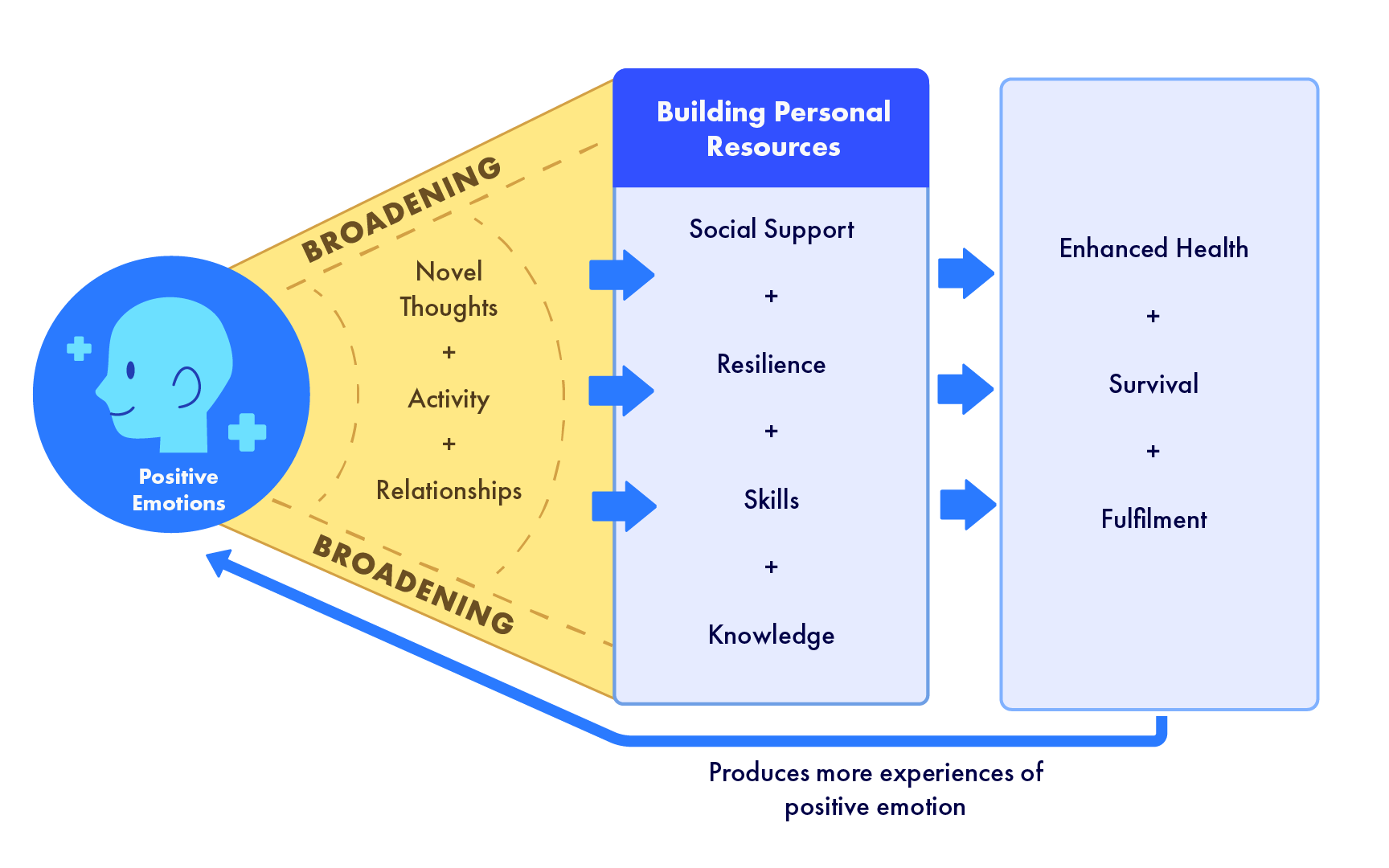

The sub-discipline of positive psychology has an array of insightful theories and frameworks to explain and predict human behavior. Among these, the Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions stands out for its emphasis on the adaptive significance of positive emotions. Proposed by Fredrickson (1998, 2001), this theory suggests that positive emotions serve to broaden an individual’s momentary thought-action repertoire, which in turn assists in building lasting personal resources, a relevant concept in the study of resilience.

The Core of Broaden-and-Build Theory

At the heart of the Broaden-and-Build Theory is the assertion that positive emotions have a unique evolutionary significance. While negative emotions narrow our focus to specific immediate actions (e.g., fight, flight, or freeze), positive emotions do the opposite. Joy, for example, can spark the urge to play, be creative, and push boundaries, while curiosity fuels exploration and learning (Fredrickson, 2001). This broadened mindset and resultant behavior allows individuals to build and accumulate lasting resources – e.g., play can build social bonds and collaboration skills, while exploration can lead to gaining new knowledge and skills.

In her pivotal work, Fredrickson (2004) indicated that the benefits of positive emotions do not merely exist in the present. Instead, they extend into the future, acting as an investment. The resources acquired through the broadening effects of positive emotions can be psychological, physical, intellectual, or social in nature, and they contribute to an individual’s ability to thrive and adapt in various circumstances.

Resilience and the Role of Positive Emotions

As noted, resilience refers to the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or even significant sources of stress (Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, & Yehuda, 2014). It’s about “bouncing back” from difficult experiences and maintaining a stable mental state despite challenges. Resilience does not eliminate stress or reduce the feelings of adversity, but it equips individuals to face them more effectively.

In this context, the Broaden-and-Build Theory offers a valuable lens to understand resilience. If positive emotions contribute to building resources and capacities, it stands to reason that they play a pivotal role in bolstering resilience. A study by Tugade and Fredrickson (2004) provides empirical support for this notion. The researchers found that individuals who often experience positive emotions demonstrate greater resilience by effectively using these emotions to bounce back from negative experiences.

The broadening effect of positive emotions facilitates creative problem-solving, fostering a more flexible cognitive appraisal of stressors and enhancing coping strategies. Over time, the accumulation of personal resources – be it strengthened social support, enhanced problem-solving skills, or increased physical well-being – sets the stage for enhanced resilience. Moreover, positive emotions can act as a buffer, attenuating the impact of negative emotions and aiding in quicker emotional recovery (Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003).

Figure 2.3: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions

The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions offers a nuanced understanding of how positivity serves as a dynamic force in our lives. Not only do positive emotions enhance our immediate scope of action, but they also contribute to the accrual of enduring personal resources. When juxtaposed with the concept of resilience, the theory underscores the importance of fostering positive emotions in building one’s capacity to navigate life’s challenges with grace and adaptability.

Time Out for Reflections on Resilience . . .

Can you think of personal experiences or examples where positive emotions have played a role in fostering resilience, helping you or someone you know bounce back from adversity?

The Wither or Thrive Model of Resilience (With:Resilience)

The Transition Curve Model

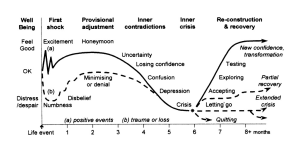

Hopson and Adams’ model of transition (1976), developed in the 1970s, provides a framework for understanding the psychological processes individuals undergo during significant life changes. This model, also known as the Transition Curve, delineates seven stages that people typically experience as they adjust to major transitions. These stages are:

- Immobilization: The initial shock or denial when confronted with change.

- Minimization: Attempts to downplay the significance of the change.

- Depression: Feelings of frustration, helplessness, or being overwhelmed.

- Acceptance of reality: Acknowledging the reality of the change and its implications.

- Testing: Exploring new ways of coping and experimenting with new behaviors.

- Search for meaning: Making sense of the transition and its impact.

- Internalization: Integrating new perspectives and behaviors into one’s life.

Figure 2.4 depicts the phases and features of the stages of transition as outlined by Hopson and Adams (1976).

These stages do not necessarily occur in a linear sequence; individuals may move back and forth between stages or experience multiple stages simultaneously. The model emphasizes the emotional and psychological aspects of transitions, highlighting that change often involves a process of loss and renewal. It emphasizes the following principles:

- Individual Differences: Not everyone will experience each stage, and the duration and intensity of each stage can vary.

- Support Systems: The availability and quality of support systems play a crucial role in how individuals navigate transitions.

- Resilience: Developing resilience and coping strategies can facilitate smoother transitions and reduce the negative impact of change.

Figure 2.4: Psychological Stages of Transition (Hopson and Adams, 1976)

The Wither or Thrive Model of Resilience (With:Resilience) model, developed by Godara and colleagues, complements and extends the work of Hopson and Adams by focusing specifically on resilience as a crucial factor in navigating transitions. While Hopson and Adams’ model outlines the emotional and psychological stages individuals go through during significant changes, the With:Resilience model provides a framework for understanding how resilience influences the experience and outcomes of these transitions.

Conceptual Framework of With:Resilience

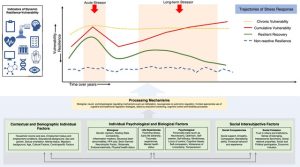

The Wither or Thrive Model of Resilience, commonly referred to as With:Resilience, offers a dynamic perspective on how individuals respond to adversity, focusing on the binary outcomes of either withering or thriving. Developed by Godara and colleagues (2022), this model proposes that resilience is not merely the capacity to return to a baseline of functioning following stress but is characterized by a bifurcation in possible responses: an individual can either experience a decline in functioning (wither) or use the challenge as a catalyst for growth and enhanced functioning (thrive). The key premise of With:Resilience is its emphasis on the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that influence these trajectories (Godara et al., 2022).

This model integrates and extends existing psychological resilience frameworks to offer a nuanced approach to mental health and resilience analysis during prolonged periods of stress (such as the COVID-19 pandemic). According to Godara and colleagues (2022), several core components determine the direction of the response to stress. These include individual traits such as optimism and self-efficacy, external supports like social networks, and the nature of the stressor itself, including its intensity and duration. The model also integrates the concept of stress inoculation, where prior exposure to manageable levels of stress can enhance one’s resilience by “training” psychological and physiological systems to handle future stressors more effectively (Meichenbaum, 1977).

Figure 2.5 depicts the With:Resilience Model.

Model Components

Higher-order Latent Construct

With:Resilience proposes a higher-order latent construct for resilience and vulnerability, moving away from single-scale approaches. This construct encompasses multiple indicators, including non-clinical mental health markers like loneliness, stress, and psychological burdens, positioning resilience and vulnerability on a continuum. This inclusive approach allows for a broader conceptualization that captures the varied ways in which vulnerability can manifest across the general population.

Dynamic Trajectories

The model outlines several trajectories of resilience-vulnerability that emerge over time, particularly in response to different and repeated stressors. These trajectories account for varying responses to stressors, including initial shock effects from short lockdowns and fatigue effects from prolonged restrictions. This aspect of the model helps in understanding how individuals can exhibit different levels of resilience or vulnerability over time.

Comprehensive Influencing Factors

With:Resilience incorporates a wide range of influencing factors, from psychological and biological to social and demographic, including the concept of social cohesion. These factors serve as predictors influencing the different trajectories of resilience and vulnerability over time.

Mediating Processing Mechanisms

The model introduces a class of variables acting as mediators between the influencing factors and the outcomes of resilience-vulnerability trajectories. These mediators include neurobiological, psychophysiological, socio-emotional, and socio-cognitive mechanisms, such as emotional regulation strategies, cognitive flexibility, and social skills. These mechanisms play a crucial role in determining whether specific factors will have detrimental or beneficial effects on mental health.

Integration Across Disciplines

The framework integrates insights from neuroscience, biology, psychology, and social sciences to provide a comprehensive understanding of resilience.

Figure 2.5: The With:Resilience Model (Godara, Silveira, Matthäus & Singer, 2022)

Application and Evidence

Empirical support for the With:Resilience model comes from historical longitudinal and experimental studies. Various research on disaster survivors found that individuals with access to robust social support networks were more likely to show signs of thriving, including increased life satisfaction and adaptive coping strategies post-disaster (Bonanno & Gupta, 2009; Boullion et al., 2020; Mao & Agyapong, 2021). Conversely, those with weaker social ties and lower personal efficacy demonstrated significant declines in psychological wellbeing, aligning with the withering pathway described in the model (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001; McNamara et al., 2021; Thoits, 2011). Moreover, the model’s predictive capability regarding stress inoculation has been supported by some studies in military training programs, where structured exposure to stressful but controlled environments significantly predicted better stress management and lower incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder among soldiers (Ahmadzadeh Aghdam et al., 2013; Forbes & Fikretoglu, 2018; Jackson et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2024). This evidence suggests that the With:Resilience model not only helps in understanding different responses to adversity but may also offer insights into potential interventions that can promote resilience.

Practical Implications

In practical terms, the With:Resilience model provides a framework for developing resilience-enhancing programs that focus on strengthening personal traits, building social connections, and carefully introducing stress inoculation techniques. Such programs can be tailored to diverse groups ranging from students facing academic pressures to employees in high-stress industries, thereby broadening the applicability and impact of this model on various populations.

The With:Resilience model offers a sophisticated framework for understanding and analyzing resilience and vulnerability in the face of prolonged stressors. By integrating a broad range of indicators, dynamic trajectories, and comprehensive influencing factors, this model provides valuable insights for developing more effective public health guidelines, policy-making, and interventions aimed at fostering resilience and protecting vulnerable populations.

Table 2.1 compares the different models of resilience, synthesizing the core concepts, components, and practical applications of each.

| Model | Key Concepts | Components | Applications and Interventions |

| Risk and Protective Factors Model | Focuses on the balance between risk factors (which increase likelihood of negative outcomes) and protective factors (which enhance likelihood of positive outcomes). | Risk Factors: Conditions that increase negative outcomes.

Protective Factors: Characteristics that mitigate risks and foster adaptive outcomes. |

Used to tailor interventions to address specific risks and strengthen protective factors. Emphasizes the complex interplay between factors, allowing for more effective support strategies. |

| Ecological Systems Theory | Emphasizes the multilayered impact of environmental systems from immediate family to broader societal and cultural contexts. Focuses on how these systems interact to affect individual development and resilience. | Microsystems: Immediate relationships and environments.

Mesosystems: Interactions between significant settings. Exosystems: Larger social structures. Macrosystems: Cultural norms. |

Holistic approach targets not only individuals but also their environments, underlining the importance of nurturing supportive settings at all levels to foster resilience. |

| Psychological Capital (PsyCap) | Focuses on developing individual positive psychological capacities within organizational settings. Highlights four primary components: Hope, Efficacy, Resilience, and Optimism (HERO). | Hope, Efficacy, Resilience, Optimism | Used in organizational contexts to enhance employee performance and satisfaction through interventions that develop these psychological capacities. |

| Conservation of Resources (COR) | Centers on the idea that stress occurs when there is a threat, actual loss, or inadequate replenishment of resources. Emphasizes the importance of resource conservation as a strategy to combat stress and foster resilience. | Resources: Valued personal, social, and material assets.

Resource loss and gain spirals. Resource investment. |

Focus on preventing resource loss and managing stress through protective measures, especially in vulnerable or marginalized populations. |

| Broaden-and-Build Theory | Posits that positive emotions broaden one’s thought-action repertoire, which helps build lasting personal resources and resilience. Highlights the role of positive emotions in enhancing an individual’s capacity to thrive in the face of adversity. | Positive emotions lead to expanded thinking and action potentials, building lasting personal resources. | Shows how fostering positive emotions can enhance resilience, supporting individuals in not only coping but thriving through difficult times. |

| Wither or Thrive Model (With:Resilience) | Explores how individuals respond to adversity, focusing on either withering or thriving outcomes. Considers the influence of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on these responses and incorporates a dynamic, system-level analysis of resilience and vulnerability. | Higher-order latent constructs of resilience and vulnerability.

Dynamic trajectories. Comprehensive influencing factors. Mediating processing mechanisms. |

Provides a framework for resilience-enhancing programs that focus on personal traits and social connections, and introduces stress inoculation techniques tailored to various populations. |

Table 2.1: Resilience Models Comparison Chart

Key Figures in Resilience Research

Norman Garmezy: The Pillar of Resilience Research

The field of developmental psychology has been richly informed by numerous pioneering researchers, but few have left as indelible a mark as Norman Garmezy. Garmezy’s work on resilience has provided critical insights into how individuals, particularly children, manage to thrive and demonstrate positive adaptation in the face of adversity and stressful life conditions. This article delves into the significance of Garmezy’s contributions to resilience research and highlights the enduring impact of his findings.

Understanding Resilience through Norman Garmezy’s Lens

To understand the true significance of Garmezy’s work, one must first grasp the essence of resilience as a construct. Resilience, in the context of developmental psychology, refers to the dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). Before the advent of Garmezy’s research, much of the attention in developmental studies had been centered around pathology and maladaptation. Garmezy, however, was intrigued by the contrasting phenomenon: Why did some children, despite exposure to severe adversities, such as poverty, parental psychopathology, or traumatic events, manage to develop into competent and psychologically healthy adults?

His interest in this area stemmed from his earlier work on schizophrenia. Garmezy observed that some children of schizophrenic parents did not show signs of psychopathology despite the considerable genetic and environmental risks associated with having a schizophrenic parent (Garmezy, 1974). This observation prompted a broader investigation into the factors that conferred resilience.

Methodologies and Pioneering Insights

Garmezy’s research approach was both systematic and innovative. He conducted extensive longitudinal studies, tracking children exposed to various adversities to identify which ones would develop problems and which would show resilience. Through these investigations, Garmezy identified three major sets of resilience factors (Garmezy, Masten, & Tellegen, 1984):

- Individual attributes, such as high intelligence, effective coping skills, and a positive self-concept. These traits often enabled children to interpret and handle challenging situations in ways that promoted their well-being.

- Family cohesion and warmth, characterized by stable and supportive family environments. Such environments acted as protective buffers, shielding children from the direct impacts of adversity.

- External support systems, like relationships with mentors, teachers, or peers, which could provide additional support, resources, and positive role models for children facing challenges.

Garmezy’s work paved the way for subsequent resilience researchers. He highlighted that resilience wasn’t a static trait but rather a complex interplay of multiple factors and systems, both internal and external to the individual (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990).

Legacy and Broader Implications

Beyond academic research, Garmezy’s work has had profound implications for intervention and prevention programs aimed at helping at-risk children. By identifying the key factors that promote resilience, practitioners can now design programs that nurture these protective attributes in children and their environments. Moreover, the emphasis on positive adaptation rather than pathology marked a paradigm shift, redirecting the focus from what’s wrong with an individual to understanding what’s right and how to promote it. Furthermore, Garmezy’s findings have broadened the understanding of human adaptability and strength. His work underscores the idea that despite experiencing adversity, with the right protective factors in place, individuals can not only survive but thrive.

Norman Garmezy’s dedication to unraveling the mysteries of resilience has left an indomitable legacy in the field of developmental psychology. His emphasis on understanding the factors that promote positive adaptation has inspired researchers, educators, and clinicians alike, offering hope and strategies to countless individuals facing adversity.

Michael Rutter and the Landscape of Resilience Research

Resilience is an inference based on evidence that some individuals have a better outcome than others who have experienced a comparable level of adversity. – Michael Rutter (2012)

Clearly, resilience is a term that has permeated various spheres of research, from psychology to business, emphasizing the importance of bouncing back from adversity and thriving. At the heart of understanding resilience lies the work of Michael Rutter, an eminent child psychiatrist and researcher whose contributions have redefined the field’s understanding of adversity, development, and protective mechanisms. His work in this domain is paramount for anyone aiming to grasp the intricate dynamics of resilience.

Michael Rutter (born in 1933) is often referred to as the “father of child psychiatry” (Rutter, 2012). His legacy in the field began in the late 20th century when he embarked on groundbreaking research on the Isle of Wight, studying childhood psychiatric disorders (Rutter, Tizard, & Whitmore, 1970). This initial exploration not only enriched the understanding of child psychiatry but also laid the foundation for Rutter’s journey into resilience research.

Rutter’s interest in resilience was catalyzed by observations of children who, despite facing extreme adversities, did not manifest the anticipated negative outcomes (Rutter, 1987). It was evident that some children exposed to the same adversities showed divergent trajectories. Some succumbed to the pressures, developing emotional, behavioral, or psychiatric issues, while others managed to thrive, exhibiting adaptability, and positive development. This paradox fascinated Rutter, pushing him to delve deeper into the factors that facilitated such resilience.

Rutter’s Theory – Protective Mechanisms

Central to Rutter’s exploration was the concept of “protective mechanisms”. He discerned between protective factors and protective mechanisms, emphasizing that it wasn’t just the presence of positive factors, such as a supportive parent, that aided in resilience, but the mechanism by which these factors interacted with risk elements (Rutter, 1999). For instance, a positive school environment could potentially counteract the negative effects of an abusive household. However, the mere existence of this environment was insufficient to guarantee resilience. The mechanisms—how children perceived this environment, utilized its resources, and incorporated its lessons—determined resilience. This nuanced understanding, highlighting the dynamic interplay of risks and protections, was revolutionary.

A Dynamic Process

Rutter was pivotal in championing the idea that resilience was not a static trait but rather a dynamic process. He argued against the misconception of resilience as an inherent, unchangeable quality, positing that it is shaped by life experiences and can vary across different domains of an individual’s life (Rutter, 2012). This insight underscored the importance of context, suggesting that resilience in one domain (e.g., academic achievement) doesn’t necessarily imply resilience in another (e.g., emotional well-being).

Equally significant was Rutter’s challenge to the deterministic notions of gene-environment interactions. He proposed the concept of “gene-environment interplay“, highlighting that genetic factors could make certain individuals more susceptible to environmental adversities, while also emphasizing that genes could increase the likelihood of individuals seeking out particular environments, a phenomenon termed as “gene-environment correlation” (Rutter, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2006). This perspective reshaped the discourse on genetic predispositions, recognizing the intricate dance between genes and environments in determining resilience.

Reflecting on Michael Rutter’s legacy in resilience research, it becomes clear that his work has reoriented and enriched the field. He moved away from deterministic and simplistic narratives, bringing forth the complexities, nuances, and dynamisms intrinsic to resilience. Researchers and practitioners today owe a significant part of their understanding to Rutter’s pioneering efforts, which emphasized the multifaceted nature of resilience, the interplay of risks and protections, and the centrality of context.

Ann Masten: Pioneering Resilience Research in Developmental Science

The conclusion that resilience is made of ordinary rather than extraordinary processes offers a more positive outlook on human development and adaptation, as well as direction for policy and practice aimed at enhancing the development of children at risk for problems and psychopathology. – Ann Masten (2001)

The field of developmental science has been shaped by numerous influential researchers over the decades. However, one of the key figures who has contributed substantially to our understanding of resilience in children and adolescents is Dr. Ann S. Masten. Recognized for her groundbreaking work, Masten’s research has revolutionized how scientists, practitioners, and policymakers approach and understand resilience in the context of adversity.

Origins and Contributions to Developmental Research

Dr. Ann Masten began her research journey by exploring the remarkable capacities of individuals who thrive despite facing significant adversities. Rather than focusing primarily on vulnerabilities and pathologies, Masten’s work has centered on understanding the processes that foster positive outcomes and resilience in the face of challenges. She is best known for her concept of “ordinary magic,” which suggests that the foundational roots of resilience are in common and ordinary processes rather than extraordinary ones. In her seminal 2001 publication, she emphasized that it is often everyday resources like positive relationships, cognitive abilities, and self-regulation that underpin resilience (Masten, 2001). This insight was groundbreaking, as it shifted the narrative from viewing resilience as a rare or exceptional quality to understanding it as a set of processes that can be nurtured and developed.

Ordinary Magic and Its Implications

One of the most significant aspects of Masten’s work lies in its practical implications. By highlighting the “ordinary” nature of resilience factors, Masten has underscored the importance of universally available resources. For instance, she has pointed out how simple, yet crucial, positive relationships, such as those with caregivers or educators, can be pivotal in fostering resilience. Such findings have broad ramifications for interventions. Instead of searching for intricate, specialized programs, her research suggests that bolstering everyday resources and systems can have profound effects on children and adolescents facing adversities (Masten, 2015).

Furthermore, Masten’s emphasis on adaptive systems has provided a broader framework for resilience. Rather than narrowing it down to individual traits or singular factors, she emphasizes the importance of viewing resilience as a product of interconnected systems, both internal and external to the individual (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). This systems-based perspective has enriched the resilience literature, urging scholars and practitioners to adopt a holistic approach when seeking to foster resilience.

Current Perspectives and Future Directions

In more recent years, Masten has continued to advance the field, incorporating insights from neuroscientific research to deepen our understanding of resilience processes. By integrating findings from brain development and function, she has offered a more comprehensive perspective on how adversity impacts the developing brain and how resilience factors can mitigate these effects (Masten & Barnes, 2018).

As the field of resilience research continues to grow, Masten’s foundational work serves as a beacon, reminding researchers of the importance of focusing on strengths and capacities. Her legacy is evident in the continued exploration of “ordinary magic” processes in various cultural and contextual settings, underscoring the universality of resilience processes.

Dr. Ann S. Masten has played an instrumental role in shaping the way we understand and approach resilience in developmental science. Through her emphasis on ordinary processes, interconnected systems, and the integration of diverse research methodologies, she has provided a rich and nuanced understanding of resilience. Her contributions serve as a testament to the importance of grounding scientific inquiry in both rigor and relevance, ensuring that findings are not only academically meaningful but also practically significant.

Emmy Werner: A Leader in Resilience Research

If we want to help vulnerable youngsters become more resilient, we need to decrease their exposure to potent risk factors and increase their competencies and self-esteem, as well as the sources of support they can draw upon. – Emmy Werner (1995)

Emmy Werner stands out as an iconic figure in the sphere of developmental psychology, primarily due to her pivotal research on resilience. As researchers delved deeper into understanding the factors that determined children’s developmental trajectories, Werner’s longitudinal studies illuminated the characteristics and environments that facilitate positive outcomes in children exposed to high-risk conditions.

Groundbreaking Kauai Study

Werner's groundbreaking study on the island of Kauai provided unparalleled insights into the world of resilience. Beginning in the 1950s, Werner, alongside her colleague Ruth Smith, embarked on a comprehensive research expedition, tracing the lives of a cohort of children born on Kauai in 1955 (Werner & Smith, 1982). These children were subjected to a plethora of adversities ranging from prenatal stress and birth complications to poverty and familial discord. Contrary to prevailing beliefs of the era, which largely emphasized the deterministic nature of early adversities leading to negative outcomes, Werner’s study revealed a surprising pattern. A third of the high-risk children studied did not display the expected developmental problems in adolescence and adulthood. These children exhibited a remarkable ability to overcome challenges, a phenomenon Werner termed as “resilience.”

Importance of Longitudinal Research

The longitudinal nature of Werner’s research is especially noteworthy, as it allowed for a detailed chronicle of these children’s lives from birth to mid-adulthood. Through meticulous observations and regular interviews, Werner and Smith dissected the myriad of factors that contributed to the resilient outcomes in this subgroup. Their findings pointed towards a combination of individual attributes, familial support, and external support systems (Werner & Smith, 1992).

Identifying Key Resilience Factors

Several of Werner’s observations are foundational to modern-day resilience research. She highlighted the role of ‘temperamental attributes‘ in resilience. Children who were active, affectionate, and had a positive social orientation were often more resilient. Moreover, these children demonstrated effective problem-solving skills, a finding that underscored the importance of cognitive capabilities in mediating adverse experiences (Werner, 1993). Beyond individual characteristics, Werner’s research shed light on the critical role of nurturing caregivers – be it parents, grandparents, or even older siblings. A consistent and supportive relationship with at least one primary caregiver served as a protective buffer against adversities. In the broader community context, the presence of supportive adults outside the family, like teachers or neighbors, further bolstered resilience.

Werner’s contribution to resilience research goes beyond merely identifying protective factors. Her work laid the foundation for interventions aimed at fostering resilience in vulnerable populations. By understanding the determinants of resilience, policymakers and practitioners could design interventions tailored to enhance those very determinants, thereby promoting positive developmental outcomes.

Time Out for Reflections on Resilience . . .

Reflect on a personal or observed experience where resilience played a crucial role in overcoming adversity.

How do Werner’s findings resonate with or explain this experience?

What resilience factors were evident?

Historical Context and Impact

Understanding Werner’s work also requires recognizing its historical significance. During a time when research predominantly focused on deficits and pathologies, Werner’s focus on strengths and positive adaptation was revolutionary. Her resilience-centric approach instigated a paradigm shift, moving the research community from a deficit model to a strengths-based model. This not only changed the way researchers approached developmental challenges but also paved the way for a more holistic understanding of human development (Masten, 2001).

Emmy Werner’s indelible mark on resilience research is evident in the vast body of literature that has since burgeoned, building upon her seminal findings. By highlighting the factors that facilitate positive adaptation in the face of adversity, Werner’s research not only reshaped academic understanding but also offered hope and a roadmap for interventions aimed at fostering resilience in at-risk populations.

Case Studies: Historical Perspectives on Resilience

Understanding resilience is significantly enhanced through real-life illustrations and historical case studies. These cases are pivotal as they illuminate the practical application and manifestation of theoretical resilience concepts.

Victor of Aveyron

Victor of Aveyron was a feral child found in the late 18th century in France, and his life offered early psychologists insight into the human capacity for resilience and adaptability. Despite living in isolation during crucial developmental years, Victor learned to engage with his surroundings and caregivers, demonstrating an innate ability for resilience and social connection (Lane, 1976).

Holocaust Survivors

Holocaust survivors endured unimaginable trauma and loss during World War II. The ability of many survivors to rebuild their lives post-war, often in new countries and with limited resources, is a testament to human resilience. These individuals often drew strength from community, personal values, and a commitment to bearing witness, highlighting the interplay of individual and communal resilience factors (Greene, 2002; Greene et al., 2012; Shmotkin et al., 2011).

Rwanda Genocide Survivors

The survivors of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, who rebuilt their lives amidst horrific personal and community loss, offer further insight into resilience. Their stories emphasize the role of forgiveness, reconciliation, and community-building in fostering resilience in the wake of mass trauma (Connolly & Sakai, 2011; Fox, 2012; Staub et al., 2005).

911 Survivors and First Responders

The events of September 11, 2001, in the United States had a long-lasting impact on survivors and first responders. Stories of resilience emerged as individuals and communities navigated the aftermath of the attacks, with many finding new purpose, connection, and strength in the face of adversity (Bonanno et al., 2006; Bonanno et al., 2023; Freedman, 2004).

COVID-19 Pandemic Frontliners

Healthcare workers, essential service providers, and countless individuals worldwide displayed remarkable resilience during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Despite facing overwhelming stress, uncertainty, and personal risk, these individuals continued to serve and support their communities, illustrating resilience in action (Baskin & Bartlett, 2021; Costello et al., 2023; Khalil, Mataria & Ravaghi, 2022; Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020; Ranter et al., 2020).

Media Attributions

- PsyCap-transparent

- COR-transparent

- Broaden-and-Build-Theory-transparent-

- Wither or Thrive Model

- The-WithResilience-model-The-graph-depicts-the-four-trajectories-of_W640

conditions or attributes that increase the likelihood of a negative developmental outcome (Masten, 2001), that can emerge from various domains including individual (e.g., genetic vulnerabilities), family (e.g., dysfunctional relationships), and environmental contexts (e.g., socio-economic disadvantages)

The aggregate impact that arises from the accumulation of various risk factors, leading to potential negative developmental outcomes.

The concept that exposure to moderate levels of risk can actually strengthen resilience, preparing the individual for future challenges.

Actions or programs designed to alter the course of events, particularly to prevent or ameliorate risk factors or to enhance protective factors.

A framework introduced by Urie Bronfenbrenner that emphasizes the multilayered effects of different environmental systems on individual development.

The closest layer to the individual in the Ecological Systems Theory, consisting of environments like family and school where direct interactions take place.

Part of the Ecological Systems Theory, encompassing the interactions between the different immediate environments of the individual, like family and school.

A layer in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory referring to the broader social system that influences an individual's immediate context but does not directly contain the individual.

In the Ecological Systems Theory, it represents the broader cultural context, including societal and cultural norms, beliefs, and values.

Part of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, it refers to the patterning of environmental events and transitions over the lifespan, as well as sociohistorical circumstances that affect an individual's development.

A construct composed of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism that represents an individual's positive psychological state of development.

As a component of PsyCap, hope refers to the motivational state based on an interactively derived sense of successful agency (goal-directed energy) and pathways (planning to meet goals).

Within the context of PsyCap, it relates to an individual's belief in their capacity to execute tasks successfully.

As part of PsyCap, optimism is the generalized expectation that good things will happen and goals can be achieved.

Assets, characteristics, or energies that individuals cherish or that aid in achieving cherished outcomes, central to the concept of stress in COR theory.

A framework for understanding stress developed by Stevan E. Hobfoll in 1989, which postulates that stress arises from the threat of loss, actual loss, or insufficient gain of resources after substantial investment.

The concept in COR theory that suggests initial resource loss or gain can lead to subsequent and amplified loss or gain, affecting the individual's stress levels and overall well-being.

The allocation of personal resources with the anticipation of future resource gain, a concept in COR theory that explains how failure to realize expected returns can cause stress.

Actions taken to prevent stress by safeguarding resources, as suggested by the implications of the COR theory.

The variance in stress experiences among different populations, explained by the COR theory as a function of pre-existing resource levels.

Groups that are more susceptible to resource loss and stress according to the COR theory, often due to lower socioeconomic status.

A sub-discipline of psychology that focuses on the positive aspects of human life, such as happiness, well-being, and resilience.

Proposed by Barbara Fredrickson, this theory suggests that positive emotions broaden an individual's awareness and encourage novel, varied, and exploratory thoughts and actions.

The evolutionary importance of certain traits or behaviors, in this case, the role of positive emotions in human development and psychological resilience.

The range of actions that thoughts can lead to; the Broaden-and-Build theory suggests that positive emotions expand this repertoire.

The beneficial roles that emotions have played in the survival and development of humans, particularly how positive emotions have helped adapt to changing environments and challenges.

The personal interpretation of a situation that ultimately influences the stress response; positive emotions can modify cognitive appraisals to enhance coping strategies.

According to Fredrickson, the physical, intellectual, psychological, or social assets that are built up through the broadening effect of positive emotions.

The process of returning to a baseline of well-being after stress or adversity, which can be facilitated by positive emotions according to the Broaden-and-Build theory.

The scientific study of the nature of disease and its causes, processes, development, and consequences.

Characteristics or features of an individual, such as intelligence and coping skills, that contribute to their ability to deal with life's challenges.

The idea or mental image one has of oneself and one's strengths, weaknesses, status, etc.

The bond or closeness among family members.

Networks and resources outside of the family, such as mentors, teachers, or peers, that provide support and assistance.

Processes or functions that increase an individual's capacity to avoid negative outcomes in the presence of risk factors.

A branch of psychiatry that specializes in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental disorders in children, adolescents, and their families.

Disorders of psychological function sufficiently severe to require treatment by a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist.

The complex interactions between genetic predispositions and environmental factors that influence individual outcomes.

The concept that an individual’s genetics may influence the likelihood of encountering certain environments that could impact their development and behaviors.

A concept introduced by Ann Masten suggesting that resilience arises from normal developmental processes and common protective factors rather than rare or extraordinary ones

Relationships characterized by warmth, care, and support, which are deemed essential for fostering resilience in children and adolescents facing adversity.

The ability to manage one's emotions, thoughts, and behaviors effectively in different situations, which is crucial for adapting to adversity and stress.

The idea that resilience is a product of interconnected systems, both internal and external to the individual, that work together to foster positive adaptation.

A field of study that investigates the structure and function of the nervous system, including the brain; relevant to understanding how adversity impacts brain development and how resilience factors can counteract these effects.

A branch of psychology that studies the psychological changes that occur throughout a person's lifespan.

A seminal study led by Emmy Werner on the Hawaiian island of Kauai that followed the lives of children from birth into adulthood to understand resilience in the face of adversity.

The innate personality traits of an individual, such as activity level, emotional reactivity, and sociability, which can influence their resilience.

The broader social and environmental setting in which an individual lives, including the presence of supportive adults outside the family, which can enhance resilience.

The recognition of the impact of research findings within the context of the prevailing beliefs and theories of the time, as with Werner's research challenging the deterministic views of child development.

The ability of an individual to maintain or regain mental health despite experiencing adversity.

A perspective in research and practice that focuses on weaknesses or problems to be fixed.

An approach that focuses on the inherent strengths and capabilities of individuals or communities and builds upon these to foster positive outcomes.

A historical case of a feral child found in France, providing early insights into innate resilience and adaptability despite severe deprivation during developmental years.

An individual's natural capacity to adapt and survive in the face of adversity, as observed in cases like Victor of Aveyron.

The relationships and bonds that individuals form with others, which can serve as a crucial resilience factor, especially after traumatic events.

Individuals who endured extreme trauma during World War II and later reconstructed their lives, serving as profound examples of resilience through community support and personal fortitude.

Core beliefs or standards that guide individuals' actions and decisions, contributing to resilience by providing a stable foundation in times of upheaval.

The act of sharing one's experiences, often traumatic or painful, as a means to foster healing and resilience, as demonstrated by Holocaust survivors.

Individuals who experienced extreme trauma during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, whose processes of forgiveness, reconciliation, and community-building are illustrative of collective resilience.

The restoration of friendly relations, which is an essential aspect of healing and resilience in post-conflict societies.

The process of creating or enhancing communal bonds, which can be a powerful mechanism for collective resilience in the aftermath of collective trauma.

Healthcare workers and essential service providers who demonstrated resilience by continuing to serve their communities under conditions of extreme stress and risk during the global COVID-19 pandemic.

A level of stress that surpasses an individual's usual ability to cope, necessitating the activation or development of resilience strategies.

A lack of certainty about the future or about the potential outcomes of events, which can challenge resilience but also spur its development.