Trauma, Adversity and Resilience

Exploring the Landscape of Resilience, Trauma, and Adversity

This chapter delves into the intricate and profound domain of human resilience in the face of adversity and trauma. It is dedicated to unraveling the complex interactions between traumatic experiences, adverse conditions, and the remarkable human capacity for resilience. Trauma and adversity, often inevitable components of human experience, can range from personal hardships like bereavement or illness to widespread calamities such as natural disasters or societal upheaval. The concept of resilience, specific to this discourse, refers to the ability of individuals to withstand, adapt, and grow in the face of such challenges, demonstrating a remarkable capacity for recovery and positive transformation.

Trauma, Adversity, and Resilience: The Triad

Understanding the Triad

The interplay between trauma, adversity, and resilience forms a complex triad that is pivotal in psychological studies and therapeutic interventions. Trauma, often resulting from deeply distressing or disturbing experiences, can lead to significant emotional, psychological, and sometimes physical distress. It encompasses a range of experiences, from personal tragedies like the loss of a loved one to large-scale events such as natural disasters or acts of terrorism. Adversity, while similar to trauma, often refers to prolonged or chronic conditions of difficulty or misfortune, such as living in poverty or enduring ongoing abuse. Resilience, the third component of the triad, is the process and outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences, especially through mental, emotional, and behavioral flexibility and adjustment to external and internal demands (Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, & Yehuda, 2014).

Trauma and Its Impact

Trauma’s impact is profound and multifaceted, influencing an individual’s emotional and psychological wellbeing. It can manifest in various forms, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders. The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2022b) categorizes trauma as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, either by directly experiencing it, witnessing it, learning that it occurred to a close family member or close friend, or experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic events. This broad definition underscores the varied ways in which trauma can be experienced and its potential impact on individuals.

Adversity and Its Challenges

Adversity, though often chronic, has its own unique impact on individuals. Chronic adversities such as poverty, discrimination, or chronic illness pose continuous challenges and can lead to a sense of helplessness or a chronic stress response. Unlike the acute nature of trauma, adversity often requires enduring coping and adaptation strategies. Research indicates that prolonged exposure to adversity can have a cumulative effect on an individual’s mental and physical health (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009).

Resilience as a Dynamic Process

As previously noted, resilience, the most hopeful element of the triad, is not a fixed trait but a dynamic process that can be developed and strengthened over time. It involves behaviors, thoughts, and actions that can be learned and developed by anyone (American Psychological Association, 2022a). Resilience is characterized by the ability to maintain or regain mental health, despite experiencing adversity or trauma. It’s not about avoiding distress but rather effectively navigating and adapting to life’s challenges. Resilient individuals are often able to find meaning in adversity, use effective coping strategies, maintain positive relationships, and draw from past experiences to manage current difficulties (Bonanno, 2004).

The interrelationship between trauma, adversity, and resilience is a testament to the complexity of human psychology. Understanding this triad is essential for developing effective therapeutic interventions and support systems. By recognizing the impacts of trauma and adversity and fostering resilience, mental health professionals can guide individuals toward recovery and growth.

Post-Traumatic Growth

The Concept of Post-Traumatic Growth

Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG) represents a fascinating area within the study of trauma and resilience, offering a perspective that transcends traditional views of recovery. PTG refers to the positive psychological change experienced as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). This transformative process is not merely a return to baseline functioning prior to trauma, but rather an evolution towards a more complex and fulfilling state of being.

The Posttraumatic Growth Model (PTG)

The Posttraumatic Growth Model (PTG) is a psychological framework that describes the positive psychological changes individuals may experience following traumatic events. Developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun in the mid-1990s, PTG posits that trauma, while challenging and often devastating, can also be a catalyst for personal development, enhanced relationships, and a deeper appreciation of life (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

At its core, PTG suggests that the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances can lead to transformative changes in five key domains: appreciation of life, relationships with others, new possibilities in life, personal strength, and spiritual change (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). The model asserts that these changes do not simply occur as a direct result of the trauma itself, but rather through the individual’s response to the trauma, including their cognitive processing and the coping strategies they employ. This process often involves a significant re-evaluation of one’s life and priorities, leading to profound shifts in perspectives and behaviors.

The Dimensions of Post-Traumatic Growth

Tedeschi and Calhoun’s seminal work identifies five key areas in which individuals may experience growth following trauma: a greater appreciation of life, relationships with others, new possibilities in life, personal strength, and spiritual change (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Each of these dimensions represents a pathway through which individuals reconstruct their life narratives and identity, often leading to a deeper sense of meaning and purpose.

- Appreciation of Life: This domain involves a renewed sense of valuing everyday experiences and recognizing the fragility and preciousness of life. Trauma survivors often report a heightened appreciation for each day, leading to a re-evaluation of priorities and a more profound gratitude for life’s simple pleasures. This shift can lead to a more meaningful and fulfilling existence, as individuals prioritize what truly matters to them.

- Relationships with Others: In the domain of relationships with others, trauma survivors frequently experience a deepening of their interpersonal connections. This can manifest as increased empathy, compassion, and a desire to support others who are suffering. The shared experience of trauma can also strengthen bonds with others who have undergone similar experiences, fostering a sense of community and mutual understanding.

- New Possibilities: Trauma can act as a catalyst for significant life changes, inspiring individuals to pursue new paths that were previously unconsidered, such as career shifts or new hobbies. Individuals often discover new paths, interests, and opportunities that they might not have considered prior to the trauma. Driven by a desire to pursue more meaningful and impactful activities, this sense of new opportunities can reinvigorate one’s sense of purpose and direction in life

- Personal Strength: Survivors often discover an unexpected inner strength, realizing that if they can survive the trauma, they can handle other challenges that life may present. Many individuals report feeling more resilient and capable after surviving trauma. This newfound strength is often accompanied by a sense of empowerment and confidence, knowing that they have overcome significant adversity. This can lead to a more proactive and courageous approach to life’s challenges.

- Spiritual Change: Spiritual change is a domain that reflects shifts in existential and philosophical beliefs. Many find that their experiences lead to a deepening or transformation of their spiritual beliefs, providing a renewed sense of hope and purpose. Trauma can prompt individuals to question their understanding of the world and their place within it, leading to spiritual exploration and growth. This might involve a deepening of faith, a redefinition of spiritual beliefs, or an increased sense of interconnectedness with all life

The Mechanism Behind Post-Traumatic Growth

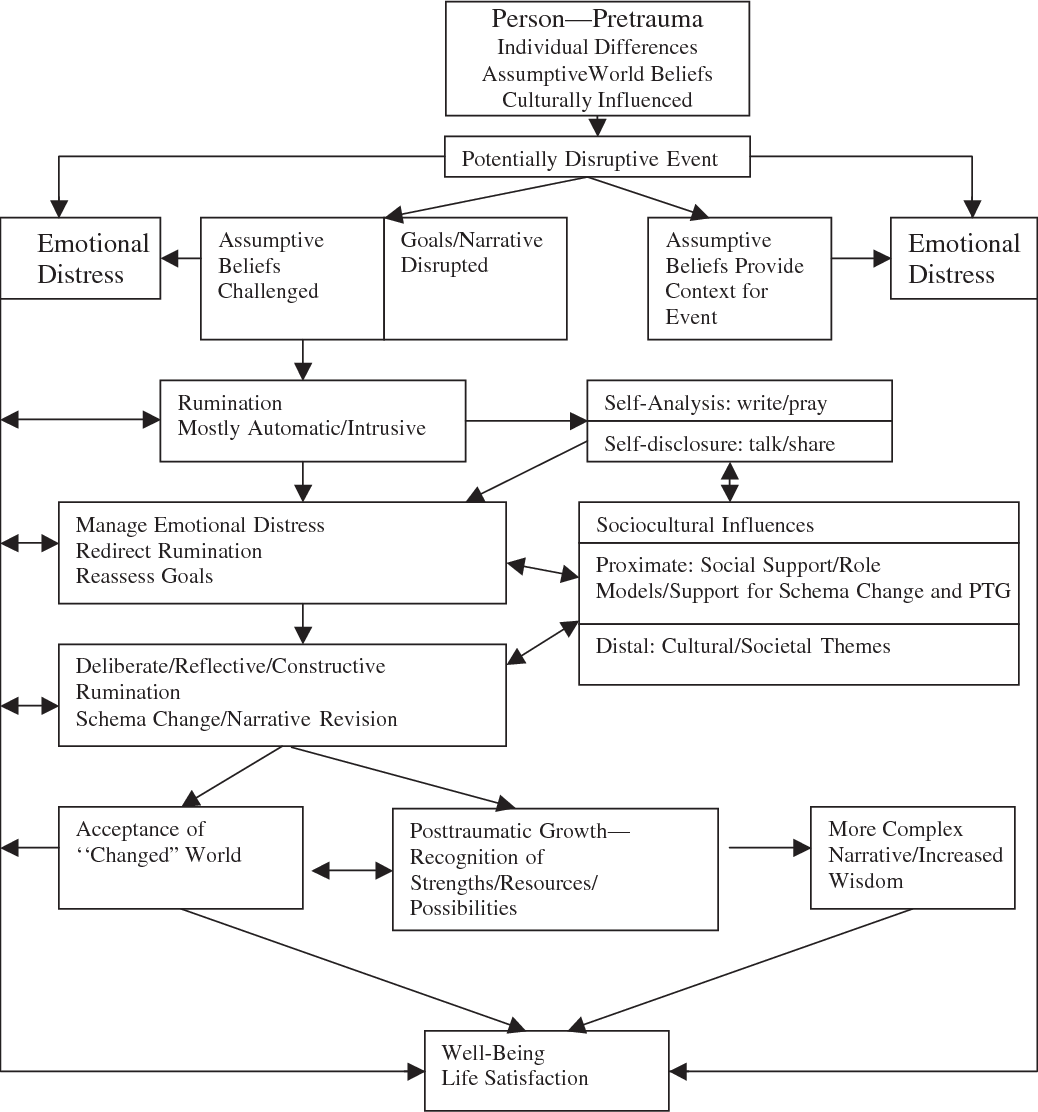

The process of PTG is typically initiated by a seismic event that disrupts an individual’s core beliefs and assumptions about the world, themselves, and their future (Janoff-Bulman, 2002). This disruption necessitates a cognitive restructuring, where individuals actively engage in trying to make sense of their trauma. It is through this process of rumination, both intrusive and deliberate, that individuals begin to reconstruct their understanding of the world and their place within it, leading to the potential for growth (Calhoun, Cann & Tedeschi, 2010; Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2014).

Figure 8.1: The Posttraumatic Growth Model (PTG) (Calhoun, Cann & Tedeschi, 2010)

Criticisms of PTG Model

The Posttraumatic Growth (PTG) model, despite its contributions to understanding the positive psychological changes following trauma, has faced several criticisms. These criticisms span methodological, conceptual, and practical aspects, reflecting the complexity and challenges inherent in studying and applying the model.

Methodological Criticisms

One major criticism of the PTG model is related to the methodological challenges in measuring posttraumatic growth. Critics argue that the tools commonly used to assess PTG, such as the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI), rely heavily on self-report measures, which can be influenced by various biases. Self-reporting can lead to social desirability bias, where individuals may over-report positive changes to conform to societal expectations or underreport negative experiences due to stigma (Frazier et al., 2001). Additionally, retrospective reporting can suffer from memory biases, as individuals’ recollections of their trauma and subsequent growth can be inaccurate.

Conceptual Criticisms

Conceptually, some scholars question whether the changes identified by the PTG model genuinely reflect growth or if they are simply coping mechanisms or defense strategies. For instance, individuals might report increased appreciation of life or improved relationships as a way to find meaning in their suffering, rather than these changes representing true personal growth (Zoellner & Maercker, 2006). This raises concerns about the validity of PTG as a construct, as it may conflate positive illusions with genuine developmental changes.

Practical and Ethical Criticisms

Practically, the emphasis on growth can sometimes inadvertently minimize the very real and ongoing suffering that trauma survivors experience. By focusing on positive outcomes, there is a risk of marginalizing or invalidating the negative aspects of trauma and the legitimate struggles of those who do not perceive significant growth. This can lead to a form of “toxic positivity,” where the expectation of growth places undue pressure on survivors to demonstrate positive changes, potentially exacerbating their distress if they do not experience such growth (Coyne & Tennen, 2010).

Cultural and Individual Differences

Another important criticism of the PTG model involves its applicability across different cultures and individual differences. The model was developed primarily within Western contexts, and its domains of growth might not be universally relevant. For example, the ways in which individuals from different cultural backgrounds interpret and respond to trauma can vary significantly, influencing the types of growth they might experience or prioritize (Weiss & Berger, 2010). This cultural variability challenges the universality of the PTG model and suggests the need for more culturally sensitive approaches.

Empirical Evidence

Empirically, the evidence supporting PTG is mixed. While numerous studies have documented instances of growth following trauma, other research has failed to find consistent relationships between trauma and positive change. Some studies suggest that reported growth may not translate into observable behavioral changes, questioning whether self-reported PTG reflects actual improvements in well-being or functioning (Park & Lechner, 2006). This inconsistency in findings underscores the need for further research to clarify the conditions under which PTG occurs and its long-term implications.

While the PTG model has provided valuable insights into the potential for positive change following trauma, it is not without its criticisms. Methodological issues, conceptual ambiguities, practical and ethical concerns, cultural considerations, and mixed empirical evidence all highlight the complexities of studying and applying the model. These criticisms suggest that while PTG can offer a hopeful perspective, it should be approached with caution and a recognition of its limitations.

Factors Influencing Post-Traumatic Growth

Several factors can influence the likelihood and extent of PTG, including personality traits, social support, coping strategies, and the nature of the trauma itself. Resilience, openness to experience, and extraversion have been linked to higher levels of growth, as these traits facilitate adaptive coping and positive reinterpretation of traumatic events (Linley & Joseph, 2004). The availability of social support plays a crucial role in providing a safe space for the expression of emotions and the reconstruction of personal narratives. The severity and type of trauma also impact PTG, with some evidence suggesting that events that are severe but not catastrophic may provide optimal conditions for growth (Prati & Pietrantoni, 2009).

Post-Traumatic Growth offers a valuable framework for understanding how individuals can not only recover from trauma but also experience profound positive transformations. It emphasizes the potential for resilience and growth in the face of adversity, providing hope and direction for those working to overcome traumatic experiences.

Time Out for Reflection on Resilience . . .

Can you think of a personal experience or a case study where trauma led to an unexpected positive change?

Consider how this change aligns with one or more dimensions of PTG.

Profiles of Resilience in the Face of Adversity: What it Takes to Adapt and Overcome

Resilience is a multifaceted construct that describes an individual’s capacity to withstand, adapt to, and recover from adversity. While the roots of resilience can be traced back to developmental psychology, examining the interplay between individual traits and environmental factors, contemporary research emphasizes a dynamic process that incorporates social, psychological, and biological components (Masten, 2014). This holistic approach helps in understanding how different individuals manage to thrive despite experiencing significant challenges.

The essence of resilience can be illustrated through various profiles of individuals who have faced considerable adversities yet have managed to not only survive but also to flourish. Such profiles often highlight a combination of internal and external factors that contribute to an individual’s resilient outcomes. Internal factors include traits such as optimism, self-efficacy, and the ability to maintain a stable emotional equilibrium.

Psychologist Susan Kobasa (1979) identified three critical characteristics—commitment, control, and challenge—that resilient individuals tend to exhibit. People who possess a strong sense of commitment are likely to engage fully with their activities and own personal relationships, even in the face of difficulty. Those with a high level of perceived control tend to see themselves as influential in the course of their own lives, rather than feeling helpless against fate. Moreover, viewing stressful situations as challenges to be overcome, rather than threats to their well-being, allows these individuals to maintain a positive attitude and a readiness to act, despite the apparent hurdles (Kobasa, 1979).

External factors also play a pivotal role in shaping resilience. These include support systems such as family, friends, and community networks, which can provide emotional backing and practical assistance during times of stress. The socio-ecological model of resilience proposed by Ungar (2011) suggests that the availability of resources that resonate with an individual’s cultural beliefs and values significantly influences resilience. This model shifts the focus from individual traits to the interaction between individual capacities and the opportunities provided by the environment (Ungar, 2011). In communities where there is a strong emphasis on collective well-being and interdependence, communal support can bolster individual resilience by reinforcing the belief that one is not facing challenges alone.

Research further indicates that resilience is not merely the absence of dysfunction following adversity, but rather an engagement in life that promotes personal growth and a deeper understanding of oneself and others. Studies on post-traumatic growth reveal that many individuals who experience significant adversity go on to report greater appreciation for life, improved relationships, and a heightened sense of personal strength (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). These findings underscore the transformative potential of adversity when navigated with resilient behaviors and support.

The profiles of resilience in the face of adversity feature a complex interplay of psychological traits, behavioral strategies, and environmental supports. Understanding this interplay can not only help in identifying why some individuals bounce back from hardships more effectively than others but also inform interventions aimed at fostering resilience in various populations. The ability to adapt and overcome challenges is not inherent but can be cultivated through strategic support and personal development.

Case Studies: Real-Life Instances of Post-Traumatic Growth

Introduction to Post-Traumatic Growth in Real Life

The concept of Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG) is not just a theoretical construct but a lived reality for many individuals who have faced significant adversities. This section presents a compilation of case studies that illustrate the transformative power of trauma and the remarkable capacity for growth in its aftermath. These real-life instances provide insight into the diverse pathways through which individuals experience PTG, highlighting the role of personal strengths, support systems, and adaptive coping strategies.

Case Study 1: Overcoming Natural Disaster

The first case study focuses on a survivor of a major earthquake, a catastrophic event that led to significant loss and trauma. This individual, initially overwhelmed by loss and grief, gradually found a renewed sense of purpose and strength. Through community support and engagement in relief efforts, they experienced a profound sense of connection and solidarity with others affected by the disaster. This experience fostered a deeper appreciation for life, enhanced empathy, and a commitment to humanitarian work, embodying the PTG dimensions of improved relationships with others and new possibilities in life (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2014).

Case Study 2: Transforming Through Chronic Illness

The second case involves an individual diagnosed with a chronic illness. Initially confronted with fear and uncertainty, this person embarked on a journey of self-discovery, eventually leading to significant personal growth. They developed new coping strategies, such as mindfulness and positive reframing, which not only helped manage their condition but also brought about a greater appreciation for the present moment and a reevaluation of personal values. This case highlights the PTG dimensions of personal strength and appreciation of life (Joseph & Linley, 2005).

Case Study 3: From Victim to Advocate

The third case study tells the story of a survivor of prolonged domestic violence who, after escaping the abusive environment, became an advocate for others in similar situations. The trauma experienced led to an initial period of struggle with trust and self-worth. However, through therapy and community support, this individual reclaimed their sense of agency and developed a strong sense of purpose in helping others. This transformation illustrates the PTG dimensions of personal strength, new possibilities, and improved relationships (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

The Role of Support and Coping Strategies

These case studies underscore the importance of supportive environments and effective coping strategies in facilitating PTG. Whether it is through community support, professional therapy, or personal coping mechanisms, these elements play a crucial role in helping individuals navigate their trauma and find pathways to growth. Real-life instances of PTG offer valuable insights into the complex yet hopeful journey from trauma to transformation. They highlight the individual variability in responses to trauma and the multitude of ways through which growth can manifest, providing a deeper understanding of the PTG process.

Media Attributions

- © Xavier Lorenzo

- 6-Figure1.1-1

A condition of hardship or afflictive circumstances. In resilience studies, adversity can refer to conditions such as family and relationship problems, health issues, or workplace and financial stressors.

Refers to deeply distressing or disturbing experiences leading to significant emotional, psychological, and sometimes physical distress. Includes a range of experiences from personal tragedies to large-scale events like natural disasters or terrorism.

The ability to adjust one's emotional responses or feelings according to the demands of different situations. This flexibility is an important aspect of resilience.

A broad concept encompassing emotional health, life satisfaction, sense of purpose, and the ability to manage stress.

A mental health condition triggered by experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event, characterized by severe anxiety, flashbacks, and uncontrollable thoughts about the event.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition – Text Revision, published by the American Psychiatric Association. It provides a standard classification of mental disorders.

A prolonged or persistent response to emotional pressure suffered for a long period, often leading to adverse health effects.

The overall impact resulting from the accumulation of various factors or experiences over time. In the context of adversity, it refers to the long-term impact of continuous exposure to challenging conditions.

The overall impact resulting from the accumulation of various factors or experiences over time. In the context of adversity, it refers to the long-term impact of continuous exposure to challenging conditions.

A state of well-being in which an individual realizes their own abilities, can cope with normal stresses of life, work productively, and contribute to their community.

Techniques that people use to deal with stress, adversity, or trauma.

A positive psychological change experienced as a result of struggling with highly challenging life circumstances, leading to a more complex and fulfilling state of being.

The process and outcome of successfully adapting to challenging or threatening experiences, especially through mental, emotional, and physical resistance or elasticity.

A dimension of PTG where individuals experience a heightened sense of gratitude and value for life, often leading to a re-evaluation of priorities.

A PTG dimension that involves deepening bonds with others, marked by increased compassion, empathy, and connection, especially with those who have faced similar challenges or provided support.

In PTG, this refers to the opening up of new opportunities or life paths as a result of experiencing and overcoming trauma.

A key area of PTG where individuals discover unexpected inner resilience and capability to handle life challenges, fostered by surviving trauma.

A transformation or deepening of personal spiritual beliefs and perspectives, often experienced as part of PTG.

A metaphor for a significant, life-altering event or trauma that disrupts core beliefs and assumptions, initiating the process of PTG.

A technique in CBT involving identifying and challenging irrational or negative thoughts to develop more effective coping strategies.

The act of thinking deeply about something; in the context of PTG, it involves reflective and often intrusive thought processes that help in reconstructing one’s understanding of the world.

Characteristics or qualities that form an individual's distinctive character, which can influence their resilience.

Assistance and comfort received from friends, family, and community, which can bolster resilience.