Building Resilience in Individuals

Resilience is pivotal in the realm of psychological well-being, particularly in the context of individual adaptation and growth. This chapter delves into the critical aspects of building resilience at an individual level. It provides an understanding of the individual experience of resilience and practical strategies for fostering resilience, a quality essential for coping with life’s challenges and adversities.

We do not have to become heroes overnight. Just a step at a time, meeting each thing that comes up, seeing it is not as dreadful as it appeared, discovering we have the strength to stare it down. – Eleanor Roosevelt

The Individual Experience of Resilience

The concept of resilience, while broadly defined as the capacity to bounce back from adversity, is experienced and manifested uniquely by each individual. This complexity arises from the interplay of various factors such as personal characteristics, life experiences, social contexts, and environmental influences.

Resilience: A Multidimensional Construct

Resilience is not a one-size-fits-all attribute; rather, it is a dynamic and multifaceted construct that varies greatly across individuals (Masten & Reed, 2002). It involves a range of processes and outcomes, influenced by an individual’s genetic makeup, psychological traits, life experiences, and social and cultural environment. Resilience is often conceptualized as a trajectory, where an individual’s path through adversity can lead to various outcomes, including recovery, sustainability, and growth (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). This perspective underscores that resilience is not merely about returning to a baseline level of functioning post-adversity but can also involve profound personal growth and transformation.

Personal Characteristics and Resilience

Certain personal characteristics have been consistently linked to higher levels of resilience. These include traits like optimism, self-efficacy, and adaptability. Optimism, the general tendency to expect positive outcomes, has been found to be a significant predictor of resilient outcomes, as it encourages individuals to view stressful situations as manageable and temporary (Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010). Self-efficacy, or the belief in one’s ability to influence events and outcomes, equips individuals with the confidence to tackle challenges effectively, a key aspect of resilience (Bandura, 1997). Adaptability, or the capacity to adjust one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors to changing circumstances, is also critical, as it allows individuals to navigate the unpredictable nature of adversities (Bonanno, 2004).

It’s your reaction to adversity, not adversity itself that determines how your life’s story will develop. – Dieter F. Uchtdorf

Traits of Resilient Individuals

Resilience, as a psychological concept, refers to a multifaceted set of psychological traits that enable individuals to adapt in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress. It is not merely the absence of distress but a proactive capacity to cope with challenges and recover from setbacks. Research in psychology has identified a set of core characteristics that are consistently observed in resilient individuals (See Table 6.1). These traits not only help in mitigating the impact of negative experiences but also foster personal growth and development. Understanding the traits that contribute to resilience can provide valuable insights into how individuals maintain mental health and well-being in the face of life’s inevitable difficulties.

| Resilience Trait | Representative Research |

| Optimism: Resilient individuals tend to maintain a positive outlook on life, even in the face of challenges. They believe in their ability to overcome difficulties and view setbacks as temporary and surmountable. |

|

| Emotional Regulation: They have the ability to manage and control their emotions effectively. This trait enables them to remain calm and composed under stress, preventing negative emotions from overwhelming them. | de Sousa, C., Vinagre, H., Viseu, J., Ferreira, J., José, H., Rabiais, I., Almeida, A., Valido, S., Santos, M. J., Severino, S., & Sousa, L. (2024). Emotions and coping: “What I feel about it, gives me more strategies to deal with it?” Psych 6, no. 1: 163-176. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych6010010

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781 |

| Problem-Solving Skills: Resilient people are proactive in facing problems. They use critical thinking to assess situations, identify solutions, and take action to resolve issues.

|

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2013). Problem-solving therapy: A treatment manual. Springer Publishing Company.

Tainter, J. A., & Taylor, T. G. (2014). Complexity, problem-solving, sustainability and resilience. Building Research & Information, 42(2), 168-181. |

| Self-Efficacy: This refers to the belief in one’s own ability to succeed in specific situations. Resilient individuals have a strong sense of self-efficacy, which motivates them to face challenges head-on.

|

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-Efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81). Academic Press.

Schwarzer, R., & Warner, L. M. (2012). Perceived self-efficacy and its relationship to resilience. In Resilience in children, adolescents, and adults: Translating research into practice(pp. 139-150). New York, NY: Springer New York. |

| Adaptability/Flexibility: The ability to adapt to changing situations and adjust one’s approach to meet new challenges is a hallmark of resilience. These individuals are open to new experiences and can pivot their strategies as needed.

|

Bonanno, G. A., Westphal, M., & Mancini, A. D. (2011). Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 511-535. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104526

Fine, S. B. (1991). Resilience and human adaptability: Who rises above adversity?. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(6), 493-503. |

| Strong Social Support: Resilient people often have a strong network of support, including friends, family, and colleagues. This support system provides emotional comfort and practical assistance in times of need.

|

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310-357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Ozbay, F., Johnson, D. C., Dimoulas, E., Morgan Iii, C. A., Charney, D., & Southwick, S. (2007). Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (edgmont), 4(5), 35. |

| Perseverance and Tenacity: They demonstrate a high level of perseverance and tenacity, refusing to give up even when faced with significant obstacles. Their persistence is driven by a deep-seated belief in their goals and values.

|

Georgoulas-Sherry, V., & Kelly, D. (2019). Resilience, grit, and hardiness: Determining the relationships amongst these constructs through structural equation modeling techniques. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, 3(2), 165-178.

Lucas, B., & Spencer, E. (2018). Developing Tenacity: Teaching learners how to persevere in the face of difficulty (Pedagogy for a Changing World series) (Vol. 2). Crown House Publishing Ltd. |

| Self-Reflection: They engage in self-reflection to understand their experiences, learn from their mistakes, and grow from their challenges. This introspection helps them develop a deeper understanding of themselves and their place in the world.

|

Crane, M. F., Searle, B. J., Kangas, M., & Nwiran, Y. (2019). How resilience is strengthened by exposure to stressors: The systematic self-reflection model of resilience strengthening. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 32(1), 1-17.

de Sousa, C., Vinagre, H., Viseu, J., Ferreira, J., José, H., Rabiais, I., Almeida, A., Valido, S., Santos, M. J., Severino, S., & Sousa, L. (2024). Emotions and coping: “What I feel about it, gives me more strategies to deal with it?” Psych 6, no. 1: 163-176. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych6010010 Falon, S. L., Kangas, M., & Crane, M. F. (2021). The coping insights involved in strengthening resilience: The Self-Reflection and Coping Insight Framework. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(6), 734-750. |

| Empathy and Compassion: Even in their own struggles, resilient individuals can empathize with others and offer compassion. This outward focus can enhance their own resilience by fostering positive relationships and a sense of community.

|

Hein, G. (2014). Empathy and resilience in a connected world. In M. Kent, M. C. Davis, & J. W. Reich (Eds.), The resilience handbook: Approaches to stress and trauma (pp. 144–155). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Peters, D., & Calvo, R. (2014). Compassion vs. empathy: designing for resilience. interactions, 21(5), 48-53. Vinayak, S., & Judge, J. (2018). Resilience and empathy as predictors of psychological wellbeing among adolescents. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 8(4), 192-200. |

| Sense of Purpose: Resilient individuals have clear values, goals, and a sense of direction in life. | Lewis, N. A., & Hill, P. L. (2021). Sense of purpose promotes resilience to cognitive deficits attributable to depressive symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 698109.

McKnight, P. E., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology, 13(3), 242-251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017152

|

Table 6.1: Resilient Traits and Relevant Research

Adversity, Trauma, and Resilience

The relationship between adversity or trauma and resilience is complex. While experiencing adversity is a precondition for demonstrating resilience, not all forms of adversity lead to positive outcomes. The nature, intensity, and duration of the stressor, as well as the individual’s resources and coping strategies, influence this relationship. Post-traumatic growth, a concept related to resilience, refers to the positive psychological change experienced as a result of struggling with highly challenging life circumstances (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). This growth is not a direct result of trauma but rather emerges from the individual’s struggle with the new reality imposed by the trauma.

Resilience in the Face of Mental Health Challenges

Resilience plays a crucial role in how individuals cope with and recover from mental health challenges. It is a key factor in the prevention of and recovery from conditions such as depression and anxiety. Resilient individuals tend to exhibit a more positive outlook, better stress management skills, and a greater ability to seek and utilize social support, all of which are protective against mental health disorders (Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, & Yehuda, 2014).

The individual experience of resilience is a complex interplay of personal characteristics, emotional regulation skills, social and environmental influences, developmental stages, and the nature of adversities faced. Understanding this multifaceted nature of resilience is crucial for developing effective strategies to foster and support resilience in diverse populations and contexts. As research in this field continues to grow, it offers valuable insights into how individuals can be supported in their journeys through adversity, recovery, and potentially toward significant personal growth.

Time Out for Reflections on Resilience . . .

Reflect on your own life experiences.

Can you identify moments or stages where your resilience was particularly tested or strengthened?

How do these experiences align with the concepts discussed in the chapter?

Life Stages and Resilience: From Childhood to Adulthood

Resilience varies significantly across different life stages. From the tender years of childhood to the complexities of adulthood, resilience manifests and develops in unique ways, influenced by a multitude of factors including environmental, biological, and psychological elements. Each life stage presents unique challenges and opportunities for resilience, suggesting that the experience of resilience is both age-dependent and context-specific. As such, it is important that resilience be understood and nurtured throughout the key stages of human development: childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

Childhood: The Foundation of Resilience

In childhood, resilience is often shaped by a combination of factors including family environment, social connections, and individual temperament. Werner and Smith (2001) in their seminal longitudinal study of children in Kauai, Hawaii, highlighted the role of protective factors such as supportive caregiving and positive school experiences in fostering resilience among children facing adversity. They demonstrated that children who developed resilience often had at least one stable and committed relationship with a supportive parent, caregiver, or other adult. These early relationships are crucial in providing the child with the emotional and social resources necessary to cope with stress and adversity (Masten, 2015). As such, interventions aimed at enhancing parenting skills and family dynamics, such as the Incredible Years program, have been found effective in promoting resilience in young children (Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2018).

Adolescence: Challenges and Opportunities

Adolescence is a critical period for the development of resilience due to the myriad of social, biological, and psychological changes occurring during this stage. Adolescents are navigating the transition from childhood to adulthood, grappling with issues of identity, autonomy, and belonging. Steinberg (2005) emphasizes the importance of fostering resilience in adolescence by providing opportunities for positive risk-taking, promoting healthy peer relationships, and ensuring a supportive and nurturing environment at home and in school. Educational settings play a pivotal role during this stage, with school-based resilience programs, such as the Resilience and Youth Development Module as part of the California Healthy Kids Survey, demonstrating effectiveness in enhancing resilience among adolescents by promoting a supportive school climate and connectedness (WestEd, 2014).

Adulthood: Resilience in the Face of Life Transitions

In adulthood, resilience is often tested through various life transitions such as career changes, relationship dynamics, parenting, and aging. The adult’s ability to adapt to these changes is influenced by earlier life experiences as well as the current support systems and coping strategies. Ong et al. (2006) highlight the significance of adaptive coping strategies, such as positive reappraisal and proactive problem-solving, in promoting resilience in adults. Additionally, the role of continued learning and personal growth, often through formal or informal education and reflective practices, is crucial in maintaining and enhancing resilience throughout adulthood (Merriam & Bierema, 2013).

Resilience is a dynamic trait that evolves throughout an individual’s life, influenced by a host of factors and experiences. Understanding the specific needs and challenges at each life stage is essential for developing effective strategies to foster resilience. From the nurturing relationships in childhood to the supportive environments in adolescence and the adaptive coping mechanisms in adulthood, each stage offers unique opportunities for building and strengthening resilience.

The Role of Physical Health in Promoting Resilience

The intricate connection between physical health and psychological resilience is a critical component in the broader narrative of individual well-being and adaptive capacity. Physical health — encompassing aspects such as nutrition, exercise, sleep, and stress management — plays a fundamental role in fostering and maintaining resilience.

Physical Health and Resilience: A Bi-Directional Relationship

The relationship between physical health and resilience is synergistic and bi-directional. Good physical health can enhance resilience by providing the physiological resources necessary to cope with stress and recover from adversity. Conversely, a resilient mindset can contribute to better physical health by promoting healthy behaviors and reducing the impact of stress on the body. Research by Southwick and Charney (2012b) illustrates that physical health factors like regular physical activity, balanced nutrition, and adequate sleep contribute significantly to the development and sustenance of resilience. This interplay suggests that interventions aimed at enhancing resilience should incorporate strategies to improve and maintain physical health.

Exercise: Enhancing Resilience through Physical Activity

Physical exercise is a cornerstone in the promotion of resilience. Regular physical activity has been consistently shown to have a profound impact on mental health, including reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression, improved mood, and increased stress tolerance (Arida & Teixeira-Machado, 2021; Childs & De Wit, 2014; Deuster & Silverman, 2013; Gerber & Pühse, 2009). Exercise promotes the release of endorphins and other neurochemicals that can enhance mood and alleviate stress, thereby contributing to greater psychological resilience. Furthermore, exercise has been associated with structural and functional changes in the brain, including growth in areas related to emotion regulation and stress response (Herold et al., 2019; Ratey & Loehr, 2011). Engaging in regular physical activity, therefore, can be a potent strategy for building and maintaining resilience.

Nutrition: The Role of Diet in Resilience

Nutrition plays a pivotal role in influencing psychological resilience. The brain requires a constant supply of nutrients to function optimally, and deficiencies in key nutrients can have a significant impact on mental health and resilience. Studies have linked diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and other essential nutrients with reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety and improved emotional well-being (Sarris et al., 2015; Sarris et al., 2014). Moreover, maintaining stable blood sugar levels through regular, balanced meals can prevent mood swings and enhance emotional stability, thereby supporting resilience. The field of nutritional psychiatry is increasingly recognizing the importance of diet in mental health and resilience, advocating for dietary interventions as a component of psychological treatments.

Sleep: Restorative Processes and Resilience

Sleep is an essential restorative process that impacts both physical and psychological health. Adequate sleep is crucial for cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and emotional regulation, all of which are integral to resilience (Lee et al., 2015; Walker, 2017). Sleep disturbances, on the other hand, can exacerbate stress and impair the ability to cope with challenges, leading to reduced resilience. Interventions that promote good sleep hygiene, such as maintaining a regular sleep schedule, creating a conducive sleep environment, and addressing sleep disorders, are essential in building resilience. Furthermore, mindfulness and relaxation techniques can be effective in improving sleep quality and, consequently, resilience.

Stress Management: Coping with Stress to Foster Resilience

Effective stress management is vital in the context of resilience. Chronic stress can have deleterious effects on both physical and mental health, impairing resilience. Techniques such as relaxation training, biofeedback, and mindfulness-based stress reduction can help individuals manage stress more effectively, thereby enhancing resilience (Cabib, Campus, & Colelli, 2012; Iacoviello & Charney, 2020). Additionally, developing a repertoire of coping strategies, including problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, can aid in navigating stressors more adaptively.

Physical health is a foundational aspect of building and maintaining resilience. Regular exercise, balanced nutrition, adequate sleep, and effective stress management are key components that contribute to physical well-being and, in turn, enhance psychological resilience. Understanding and leveraging these relationships can provide valuable insights and strategies for individuals and practitioners alike in the pursuit of resilience.

Time Out for Reflections on Resilience . . .

Reflect on a personal experience where a change in physical health practices led to noticeable changes in your resilience or mental health.

Intervention Strategies for Individual Resilience

The capacity to adapt to stressors and bounce back from adversity has been a focal point in psychological research due to its role in fostering mental health and well-being (Smith et al., 2008). Various intervention strategies can be employed to build and maintain resilience in individuals. Generally speaking, tailored approaches that cater to the diverse needs of individuals across different life stages and circumstances will be the most effective in fostering long-term growth and adaptability.

Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches

Central to the promotion of individual resilience is the cognitive-behavioral approach, which postulates that the modification of thought patterns and behaviors is integral to fostering psychological resilience (Neenan, 2017; Smith & Hollinger-Smith, 2015). Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the set of intervention strategies associated with this perspective, is predicated on the understanding that an individual’s thought process significantly impacts their emotional and behavioral responses (Beck, 2011). This perspective advocates for the restructuring of maladaptive cognitions and the enhancement of adaptive behaviors. By identifying and reframing negative, irrational thoughts, CBT aids in developing more effective coping strategies, thereby fostering resilience.

Intervention techniques such as cognitive restructuring, problem-solving training, and stress inoculation training are central components of CBT that contribute to resilience building. Specifically, cognitive restructuring – which involves identifying and challenging irrational or negative thoughts – and behavioral activation – which focuses on engaging individuals in activities that are likely to elicit positive emotions and outcomes – are instrumental in this process (Robertson et al., 2015). Schmidt and colleagues (2010) emphasize the importance of these techniques in enhancing an individual’s ability to perceive and interpret stressors more adaptively, leading to a more resilient outlook. These strategies are built on the foundational understanding that resilience is not an innate trait but rather a skill that can be cultivated through systematic and deliberate practice.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness-based interventions have gained prominence in resilience training, with empirical evidence supporting their efficacy in enhancing individual resilience (Keng et al., 2011). Mindfulness, rooted in Eastern contemplative traditions, is defined as non-judgmental, present-moment awareness (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). As such. equips individuals with the capacity to observe their thoughts and emotions without being overwhelmed by them. This ability is crucial in managing stress and adversity, hallmarks of resilience. Programs such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) integrate mindfulness practices with cognitive therapy techniques to foster a more adaptive response to stress and prevent relapse in depression (Kuyken et al., 2016). Studies by Garland et al. (2011) have shown that mindfulness practices enhance positive reappraisal, the process of reinterpreting a situation to find a positive angle.

Emotional Regulation Strategies – The Process Model of Emotional Regulation

Emotional regulation is a core component of resilience, entailing the ability to manage and modulate emotional responses to stressors effectively. Gross’s (1998) Process Model of Emotional Regulation provides a framework for understanding how individuals can influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions. Strategies such as cognitive reappraisal, which involves changing the interpretation of a situation to alter its emotional impact, and acceptance, which entails non-judgmental acknowledgment of emotional experiences, are critical in building resilience (Gross, 2002). These techniques enable individuals to navigate emotional challenges more adaptively, thereby enhancing their capacity to rebound from adversity.

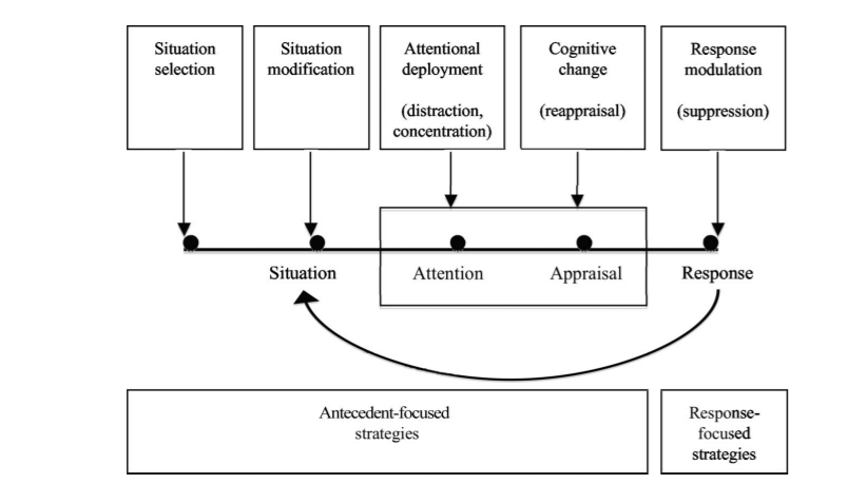

The Process Model of Emotional Regulation is grounded in the understanding that emotions are dynamic processes that unfold over time, involving multiple steps from the initial appraisal of a situation to the eventual response. According to Gross (1998), emotion regulation can be divided into five primary stages: situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation (See Figure 6.1).

In the first stage, situation selection, individuals choose to approach or avoid certain situations based on the emotions they anticipate those situations will elicit. For instance, one might choose to avoid a social gathering to prevent feelings of anxiety. This proactive strategy allows individuals to manage their emotional experiences by controlling their exposure to potentially emotion-evoking contexts. The second stage, situation modification, involves altering the external environment to change its emotional impact. An example of this could be rearranging a workspace to reduce stress and increase comfort, thereby influencing the emotional tone of the situation.

The third stage, attentional deployment, refers to directing one’s focus within a given situation to regulate emotions. Techniques such as distraction or concentration on certain aspects of the environment can help shift emotional responses. A person might focus on the positive aspects of a challenging task to mitigate feelings of frustration. The fourth stage, cognitive change, involves reinterpreting or reappraising a situation to alter its emotional significance. This cognitive reappraisal is a particularly powerful strategy, as it can transform the way a situation is perceived and, consequently, the emotional response it triggers. Viewing a stressful event as a learning opportunity rather than a threat can reduce anxiety and promote resilience.

Finally, response modulation entails influencing the physiological, experiential, or behavioral aspects of an emotional response after it has been generated. This can include techniques such as deep breathing to reduce physiological arousal or using expressive suppression to hide outward signs of emotion. While response modulation can be effective in the short term, it is often considered less adaptive than antecedent-focused strategies (Gross, 1998).

Figure 6.1: Process Model of Emotion Regulation

Psychology of Human Emotion: An Open Access Textbook Copyright © by Michelle Yarwood

Reproduced from “Emotion Regulation: Conceptual Foundations,” by J.J. Gross and R. A. Thompson, 2007, in J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of Emotion Regulation, p. 10, Guilford Press. Copyright 2007 by Guilford Press.

Gross’s model highlights the importance of timing in emotion regulation strategies, distinguishing between those that occur before an emotional response is fully generated (antecedent-focused) and those that occur after (response-focused). Antecedent-focused strategies, such as situation selection and cognitive reappraisal, are generally more effective in achieving long-term emotional well-being because they address the root causes of emotions rather than just their symptoms. Conversely, response-focused strategies like suppression may have negative long-term effects, such as increased physiological stress and reduced social support.

The strength of the Process Model of Emotional Regulation lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how individuals can influence their emotional experiences and responses. By identifying the stages at which different regulation strategies can be applied, the model offers valuable insights into the mechanisms of emotion regulation and the effectiveness of various techniques and underscores the dynamic and multifaceted nature of emotions and the critical role of regulation in promoting psychological health and well-being.

Positive Psychology Interventions

Positive psychology interventions, focusing on cultivating positive emotions, behaviors, and cognitions, also play a significant role in building resilience. According to Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000), these interventions aim to enhance individual strengths and virtues, contributing to greater resilience. Techniques such as gratitude journaling, strength identification, and fostering optimism are examples of positive psychology interventions that have been found to bolster resilience (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Resilience Training Programs

Structured resilience training programs, often encompassing elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness, and emotional regulation, have been developed to systematically build resilience skills. Programs such as the Penn Resilience Program (PRP) and the Resilience Builder Program (RBP) are designed to provide individuals with practical skills to enhance their resilience. Such programs have been found to be effective in various populations, including students, military personnel, and corporate employees, illustrating the universality and applicability of resilience skills across different settings (Reivich & Shatté, 2002; Saltzman et al., 2011).

Social Support and Interpersonal Skills

The role of social support and the development of interpersonal skills in resilience cannot be overstated. Developing strong, supportive relationships is crucial for resilience. Research indicates that social support provides emotional, informational, and practical help, which is essential during times of stress, crisis, and adversity (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Interventions that focus on enhancing interpersonal skills, such as communication and empathy, contribute to building and maintaining these supportive relationships.

Physical Health and Resilience

As noted above, the role of physical health in enhancing resilience is noteworthy. Regular physical activity, adequate sleep, and a balanced diet contribute significantly to overall well-being and resilience (Fox, 1999; Walker, 2017). Physical health interventions such as exercise programs and nutrition counseling are important components of a comprehensive resilience-building strategy.

Building resilience in individuals is a multifaceted process that involves cognitive, emotional, social, and physical components. The intervention strategies discussed above — from cognitive-behavioral approaches to positive psychology interventions — provide a foundation for enhancing individual resilience and helping individuals adapt and thrive in the face of life’s challenges.

Case Studies: Enhancing Individual Resilience

Truly understanding the ability to recover from setbacks and adapt to challenging circumstances is enriched through the exploration of real-life cases. Case studies illuminate the multifaceted nature of resilience and provide insights into the practical application of resilience-building strategies across diverse contexts. The following section presents a series of case studies that exemplify how resilience can manifest in individuals facing various life challenges and how we can use these real-life experiences to facilitate the development of resilience in ourselves and others.

Case Study 1: Overcoming Childhood Adversity

The first case study focuses on a child, Emma, who faced significant early-life challenges, including parental divorce and bullying at school. Through a combination of psychological counseling, family therapy, and involvement in supportive extracurricular activities, Emma developed key resilience skills. She learned coping mechanisms, such as cognitive-behavioral techniques, to manage her emotions and reactions to stress. Her case exemplifies the work of Masten and Reed (2002), who emphasized the “ordinary magic” of resilience as a common phenomenon that can be developed through everyday resources and support.

Case Study 2: Building Resilience in Adulthood

John, a middle-aged adult, encountered a series of career setbacks and personal losses, leading to a period of depression. His journey to resilience was facilitated by a personalized resilience training program, which included mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and physical fitness routines. These interventions align with research by Southwick and Charney (2012a), who found that resilience can be bolstered through strategies like mindfulness and physical wellness, especially in adults facing life transitions.

Case Study 3: Physical Health and Resilience

The third case study highlights Maria, an elderly woman managing chronic illness. Her resilience was significantly enhanced through a tailored exercise program and nutritional planning, alongside regular medical check-ups. This multidimensional approach to managing physical health as a component of resilience is supported by the findings of Wagnild (2009), who identified a strong correlation between physical health and psychological resilience, particularly in older adults.

These case studies underscore the importance of a holistic approach to enhancing individual resilience. Whether through psychological interventions, physical health management, or supportive social environments, resilience can be cultivated and strengthened at any life stage. The evidence from these cases provides valuable insights for practitioners and individuals alike, emphasizing the potential for growth and adaptation in the face of adversity.

Media Attributions

- © FatCamera

- kike-vega-F2qh3yjz6Jk-unsplash © Kike Vega

- EmotionalRegulation2

Distinct phases in human development, each characterized by unique challenges and opportunities. In this context, the primary stages are childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

The early stage of human development, where foundational aspects of resilience are shaped by factors like family environment, social connections, and temperament.

A life stage where resilience is often tested through various life transitions such as career changes, relationship dynamics, parenting, and aging.

A critical developmental period marked by social, biological, and psychological changes. This stage involves the transition from childhood to adulthood, with a focus on identity, autonomy, and belonging.

Conditions or attributes in individuals, families, communities, or the larger society that help people deal more effectively with stressful events and mitigate or eliminate risk.

A type of caregiving that provides emotional and social support, essential for fostering resilience in children.

An intervention program designed to enhance parenting skills and family dynamics, thereby promoting resilience in young children.

Engaging in activities that are challenging yet provide opportunities for growth, particularly important during adolescence.

Educational programs aimed at enhancing resilience among students, often by promoting a supportive school climate and connectedness.

Actively addressing problems and seeking solutions rather than avoiding or ignoring them.

A mutual, two-way relationship where each element influences and is influenced by the other.

Neurochemicals produced in the brain that reduce pain and boost pleasure, resulting in feelings of well-being.

Essential fats found in food, important for brain health, and associated with reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Substances that can prevent or slow damage to cells caused by free radicals, thereby improving physical and mental health.

An emerging field focusing on the use of food and diet as a key component in the treatment of mental health issues.

The ability to manage and respond to an emotional experience in an appropriate manner.

Practices and habits that are conducive to sleeping well on a regular basis, important for maintaining resilience.

Techniques that help reduce muscle tension and induce a state of calm, used to manage stress and improve resilience.

A technique that teaches control over involuntary physiological processes to improve health and performance, often used in stress management.

A coping strategy that involves managing emotional responses to a stressor, particularly suited to situations appraised as uncontrollable.

The capacity of an individual to maintain or regain psychological well-being in the face of adversity, challenge, or threat.

A form of psychotherapy that focuses on identifying and modifying maladaptive thought patterns and appraisals. In resilience training, CBT aims to develop adaptive appraisal styles and coping strategies.

A technique in CBT involving identifying and challenging irrational or negative thoughts to develop more effective coping strategies.

A method that focuses on engaging individuals in activities to elicit positive emotions and outcomes, used in resilience building.

A structured program developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn to reduce stress and anxiety through mindfulness meditation and practices.

A therapeutic approach combining mindfulness practices with cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in depression.

A cognitive process where individuals reinterpret a distressing situation in a more positive or meaningful way, contributing to enhanced emotional well-being and resilience.

A strategy for changing the interpretation of a situation to alter its emotional impact.

Techniques focusing on cultivating positive emotions, behaviors, and cognitions to enhance individual strengths and resilience.

A positive psychology practice of recording things one is grateful for, contributing to resilience.

Structured programs incorporating elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness, and emotional regulation to build resilience skills.

A resilience training program offering practical skills to enhance resilience across various populations.

Abilities like communication and empathy that contribute to building and maintaining supportive relationships for resilience.

The state of physical well-being where the body functions optimally, free from disease, and able to perform daily activities without limitation.

Psychological methods that emphasize modifying thought patterns and behaviors to foster resilience and psychological well-being.